4 minute read

Stickwork

Stickwork COMING SOON:

When ecologist Dan Spada looks at a stand of Scotch pine, well, he doesn’t have much love. “It’s typically looked at as an invasive species,” he says. “It’s not native. And it’s not of much use for anything except pulp.”

But when he showed artist Patrick Dougherty around the Scotch pine grove near Wild Walk last fall, where Dougherty will construct his upcoming installation at The Wild Center, Spada got an entirely new perspective on something he had taken for granted.

“When he started talking about his vision for the installation, how it was going to wrap around the trees and become part of it—the color and the form and the texture of the bark—I began to appreciate it even more than I had before,” he says.

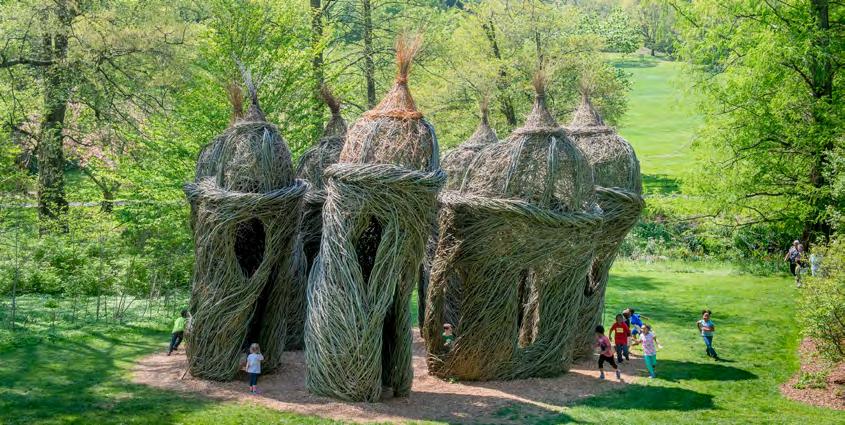

Dougherty’s sculptures, which have been erected around the world, weave branches and saplings to make fanciful, lifesize structures that visitors can walk through. He does all his

ABOVE: A Waltz in the Woods (2015). Morris Arboretum of UPA, Philadelphia. Photo: Rob Cardillo BELOW: Dan Spada (left) consults with Patrick Dougherty.

WE WANT YOU!

Patrick Dougherty’s rambling Stickwork sculpture is an all-hands affair—and we’re looking for help. We need volunteers to cut and bundle branches, and then strip them of leaves, before the sculpture starts, and still more to weave, under Dougherty’s direction, later on. We’re looking for people who are enthusiastic and able to follow directions, but do note: this is physically demanding work. Shifts are four hours apiece. If you’d like to learn more, email lfavreau@wildcenter.org.

work on-site, relying on a team of volunteers to build the final product. Dougherty will be here in August for about two weeks while the sculpture goes up.

The materials he’ll likely use, red maple and pussywillow saplings, will come from Adirondack landowners. Spada says they’re ideal species to harvest for something like this. Pussywillow spring back at will: “You can cut them and cut them and cut them, and that’s not going to harm them at all,” he says. And the red maple being harvested would likely be used for pulp or chips, not timber.

As far as the site itself, Spada says the Scotch pine was likely planted decades ago. Someday, it will be overtaken by native species. In the meantime, visitors will have a window to contemplate their own participation in the transition. “I deal with the forest from a scientific perspective, and he deals with the forest from an artist’s perspective,” Spada says. “It was nice to get together and see how our views blended.”

Will Work FOR FOOD

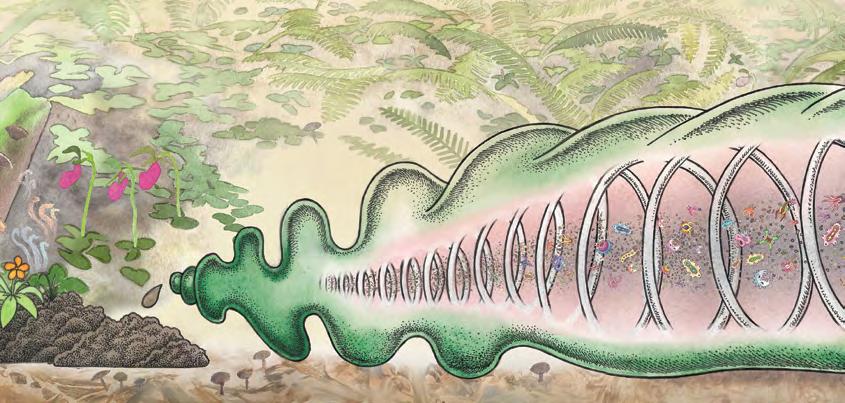

The stars of one of The Wild Center’s newest attractions are too small to be seen.

They’re microbes, and there are 15 quintillion* of them inside our shipping-container-sized drum composter located at the edge of our parking lot. (There are half that many grains of sand on the entire planet.)

Every day, those single-celled organisms are hard at work converting food scraps to compost. It’s a process that does more than turn waste to something useful. It can even help combat climate change. Because when food is composted, it becomes all-natural fertilizer. But when food is sent to a landfill, it rots and releases methane, a greenhouse gas.

And lots of food is sent to landfills in the United States—150,000 tons a day, in fact. So every time we divert waste, we’re helping the planet.

Every day, we put about 250 pounds of waste from our cafeteria and two local schools into the composter. Even if you can’t see the microbes, you can tell they’re at work: The decomposition process can make the pile 140˚F or hotter.

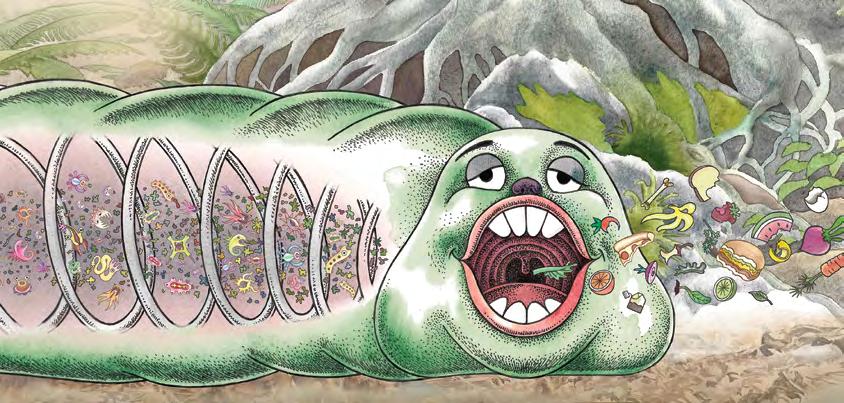

You may be able to smell the process, especially on a hot day. You can see the pile of loamy, soil-like compost curing outside of the container. And you can follow the process on a 40-foot-long, 8-foot-tall banner illustrated by Saranac Lake artist Peter Seward, whose art is featured on this page.

To Charlie Reinertsen, our exhibit developer, getting to see composting at work is a way to understand a natural process each of us can try at home. “Composting is something that’s hard to observe,” he says. “Microbes are too small to see, and it takes too long to witness a banana peel transforming into compost. This exhibit is all about bringing that process to life through illustration.”

One teaspoon of healthy soil is home to more microbes than there are humans on the planet