4 minute read

Highway of Tears

Advertisement

By Bree Gerritsen

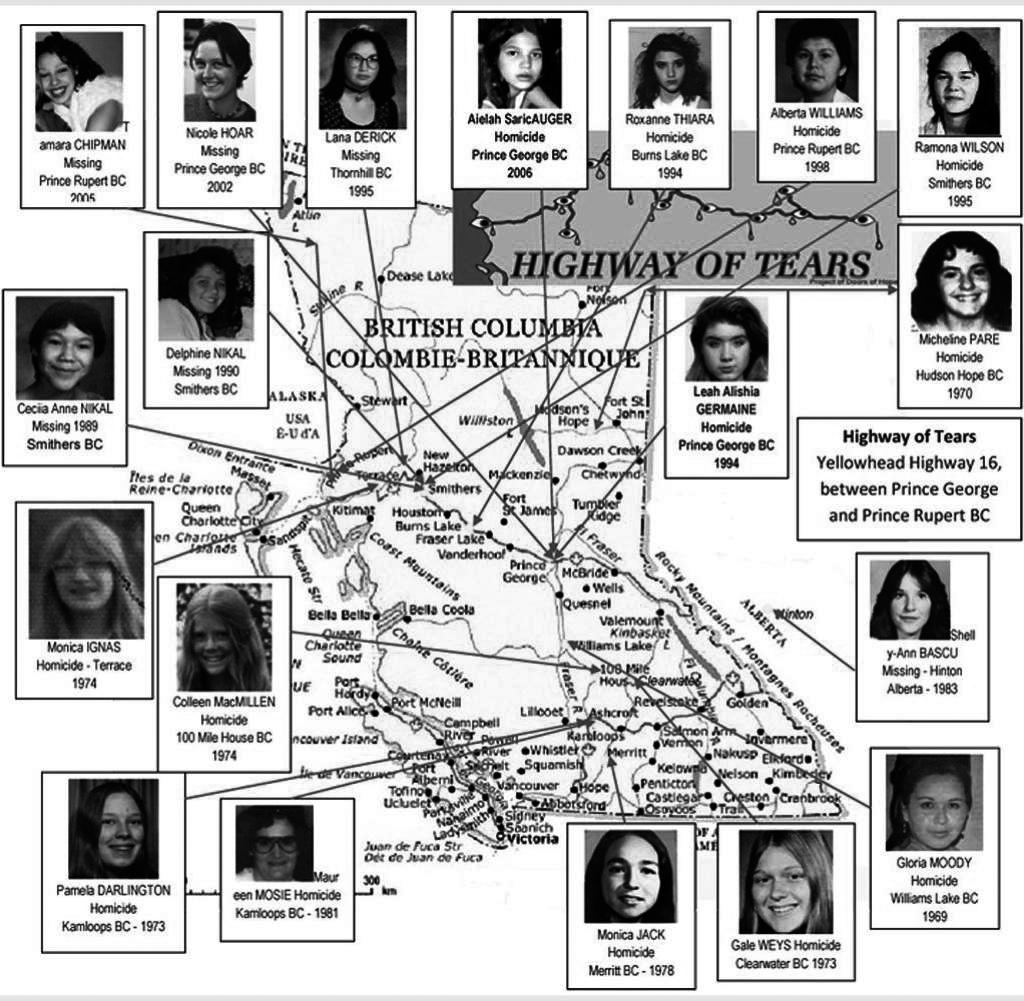

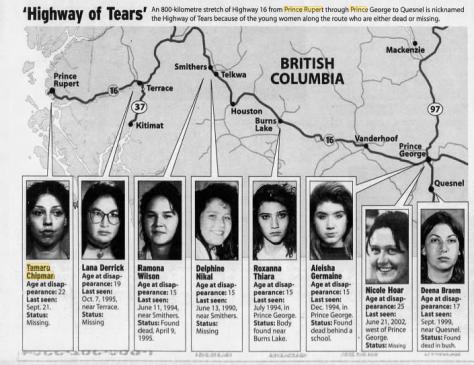

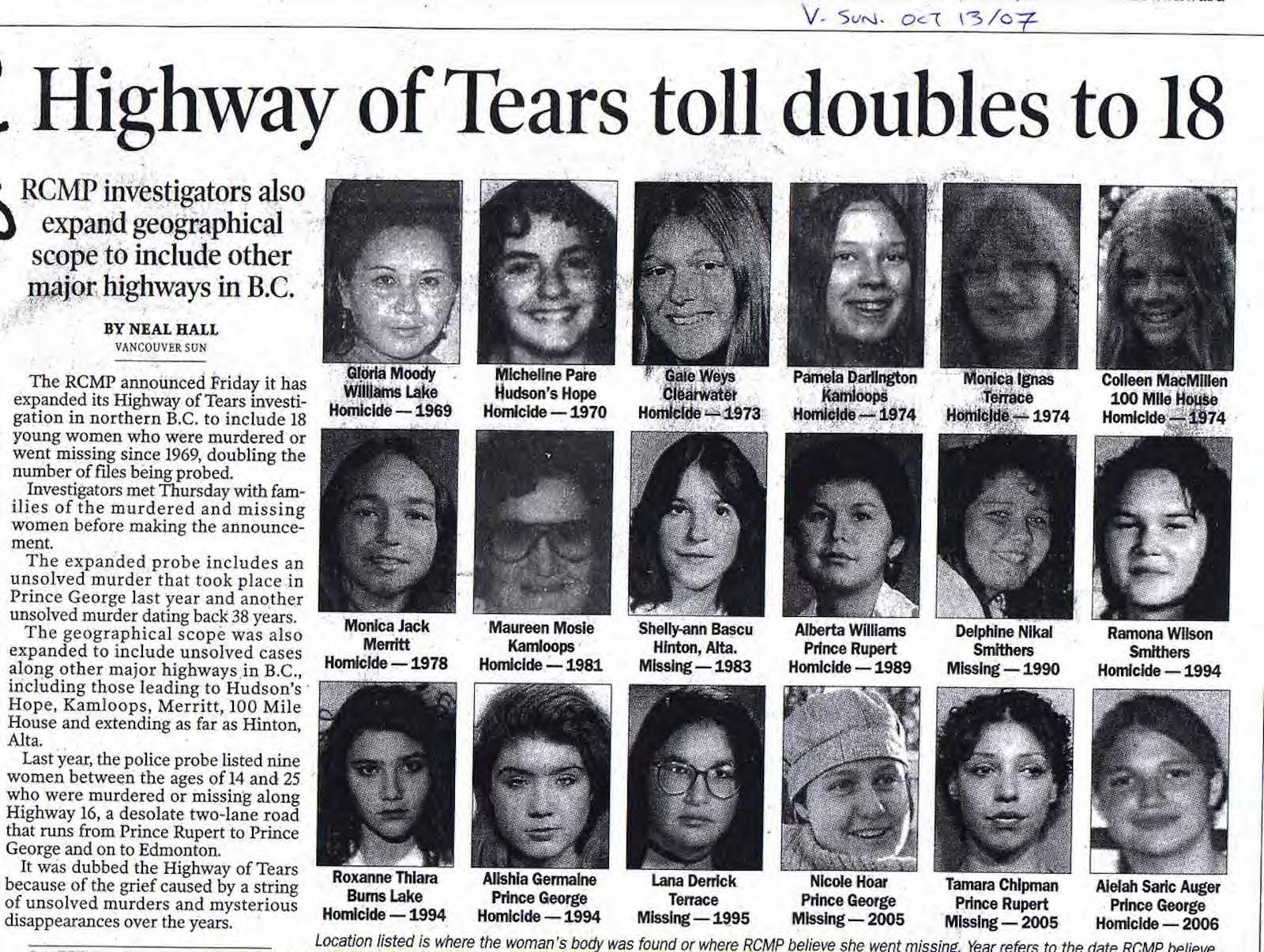

There were 18 known murders and disappearances from the Highway of Tears from 1969 to 2006. 10 of these were indigenous women. From 1980 to 2012, almost 1,200 aboriginal women were murdered or went missing in canada. This isn’t just a scary story, it’s the terrifying reality for aboroginal women and girls living in Canada. The justice system has failed in keeping them safe. The exact number of murdered and missing girls in these areas is unknown, in large part due to minimal resources and efort provided by the local police department. In a desperate attempt to fnd missing girls the community has taken measures into their own hands and is searching the Red River themselves after the failure of the justice system to provide closure. Disproportionate rates of violence towards indigenous women have been ignored by the government even when brought to their attention through movements such as MMIW crisis (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women) - a group which organises peaceful protests to spread awareness around missing indigenous women in hopes of their cases being solved. The chair of MMIW Texas, Jodi Voice Yellowfsh, became involved after the disappearance of Savannah Greywind. Savannah was 22 years old and pregnant when she disappeared. On the 19th of August 2017 she was asked by her neighbour, Brooke Crews, to model a dress she had made. Brooke lived upstairs with her partner, William Hoens. Savannah agreed and told her mother and boyfriend her plans with Crews. This was the last time her family ever heard from her.

Savannah’s mother called the police and reported her daughter missing. The police searched the neighbours house but turned up nothing. Frustrated by their lack of results, Savannah’s mother went to a local reporter, accusing the police of not taking her daughter’s disappearance seriously. When police looked further into the case they heard Crews and Hoens had a new baby at home. They had found no sign of a baby when they originally searched the apartment which raised suspicions, leading to another search of the apartment. The search found a baby girl in the apartment and Crews and Hoens were immediately arrested. Crews and Hoens had murdered Savannah and cut the baby out of her stomach. During the initial search of the apartment the baby had been under a blanket next to Hoens and Savannah’s body had been in the closet. Crews and Hoens were both sentenced to life in prison, but nothing would make up for the carelessness of the police’s searches in Savannah and her family’s time of need. The baby was left with the father (Savannah’s boyfriend), but there will forever be a hole in the family left by the police’s ineptitude. Jodi says this particular case inspired her, as Savannah reminded her of friends from college, her niece and her

sister. The challenges she faces while trying to help with this crisis stem from the way indigenous people have always been treated. “Many people in this world view our people as disposable”. As for the justice system, she feels as though no matter how many times they are asking for help with this crisis they are ignored. The police are an obstacle and are quick to call missing people runaways and ignore the issue. This just continues to prove the racism in the justice system that is prevalent against indigenous people. Many protests have attempted to bring awareness to the crisis. These have been a call to action for the Canadian and American governments and the way the justice system has been handling it. Protestors often paint a red hand print over their mouths to represent the silence that has been forced upon the indiegnous community. In 1994 the Violence Against Women Act was establised. However, this failed to include specifc protections for Native women. In 2013 this act was amended so tribes have jurisdiction over domestic violence cases against Native Americans committed on tribal lands. In 2019 this was again changed to further tribal jurisdiction to include acts of sexual violence and stalking. In November 2020 President Trump signed an order forming a task force to specifcally address MMIW.

This was initially met with gratitude from the indigenous community, but complaints were made about a lack of funding, and lack of tribal representation on the force. Similar task forces have been established in several states across the US in an efort to address the crisis. These include Washington, Arizona, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota. These actions have helped the indigenous community feel more safe, but lots still needs to be done. Aboriginal communities are still failed by the system, left entirely to fend for themselves.