12 minute read

In Life And Death, A Fervour For Fish

The Bengali custom of Matsyamukhi—or the symbolic return to fish-eating after bereavement— is one among a complex web of cultural and religious customs in the Indian subcontinent that help communities navigate the landscape of loss.

TEXT Priyadarshini Chatterjee ILLUSTRATIONS Priyanka Pandit

It’s been years but it feels like yesterday,

even if the memories only flash by in discordant spurts. The white shamiyana on the terrace, the sudden rush of guests at lunch time, stray bursts of laughter, a dramatic spat in the cooks’ tent, my sister singing my grandmother’s favourite shyama sangeet (a genre of devotional songs) to a rapt audience of great aunts and uncles, in the living room downstairs… Most of all, perhaps strangely so, I remember the food. There were trays heaped with batter-fried topshe (mango fish) and stacks of paturi; thick paves of bhetki (barramundi) slathered with a rich marinade of mustard, wrapped in banana leaves and cooked on a griddle; unctuous steaks of catla drenched in chilli-red gravy, ladled onto mounds of longgrained rice; and doi parshe, whole mullets, fried and stewed in a yoghurt and poppy-seed sauce, of which everyone sang praises.

All afternoon, my aunt stood in one corner, swivelling her eyes around the gathering, signalling the servers every now and then to bring out another round of this or that.

“More rice here,” she hollered, every time she saw an almost empty sal leaf platter, while my father and uncle took turns drifting from one table to another, imploring guests to eat well. Any awkwardness around the eating, considering the solemnity of the occasion, was quickly mitigated by the assurance that it was all for the satisfaction of my grandmother’s recently departed soul.

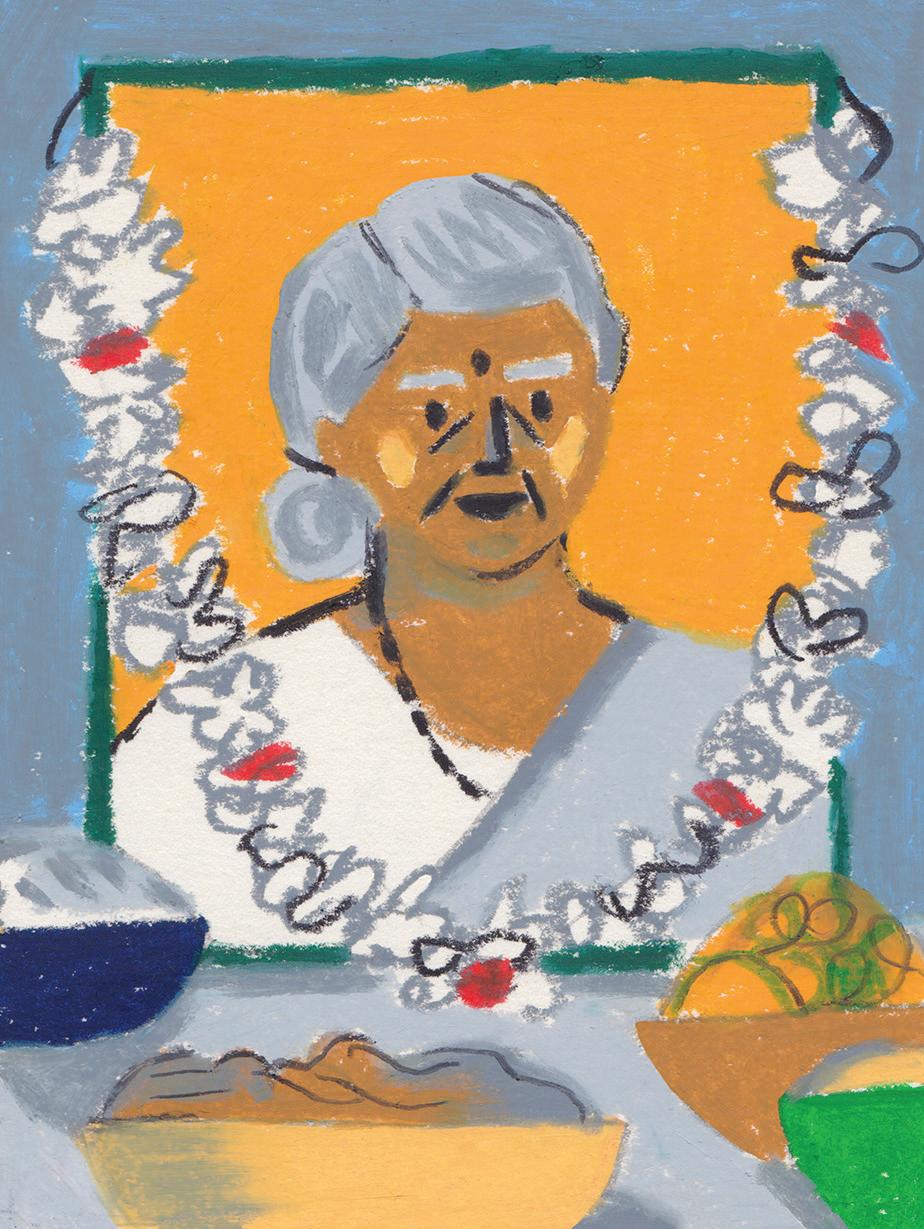

At the far end of the terrace, propped up on a table lined with a pristine white cloth, stood a framed photograph of my paternal grandmother, my Thamma, half-hidden by fat garlands of rajanigandha (or tuberose) and wraithlike tendrils of sandalwood-scented smoke from burning incense sticks. The afternoon's feast, flush with fishy excess, was the culmination of her obsequial rites riddled with myriad rules, rituals and sacraments that followed her death 13 days prior.

That morning, the funeral priest had dropped by to anoint every member of the family with a dab of turmeric and mustard oil to mark Niyam Bhango, which literally means “breaking of rules” in Bengali. He too was sent home with what my uncle dubbed as a respectable dakshina (or honorarium) and a whole catla fish, massive in size. That was the custom.

“Now we can eat everything,” a cousin winked at me, making no effort to hide his rapacious enthusiasm for returning to the pleasures of life. The ceremony, I learnt, was the symbolic release from the strict rules of abstinence that circumscribe the period of asauch or pollution arising from death. The concept of asauch is premised in the notions of ritual purity and impurity that underpin the complex fractal of Hindu beliefs and caste dynamics. In Bengal, this means the end of the period of strict vegetarianism when fish, the region’s cherished staple, is verboten. The return to “fish-eating” is, in fact, the highlight of the ceremony, also known as Matsyamukhi, which loosely translates to “putting fish in the mouth.”

In his 1931 essay, The Cultural Significance of Fish in Bengal, anthropologist Tarak Chandra Das writes,

“On this day, which falls on the first ceremonially suitable day after the Sraddha ceremony, all the relatives especially the agnates, sit together at a feast when fish is served, for the first time to the observers of the taboos. The nearest agnate belonging to the superior grade of agnatic kinship, and preferably older in age, puts a piece of fish from his own plate on that of the chief mourner and this ends the period of taboos for all concerned. Thus, fish here serves as an emblem of all the taboos taken together and the partaking of it removes all other taboos automatically.”

Das also points out that the practice is “dissociated from Brahmanical rituals” (and the associated insistence on vegetarianism) and observed as a “social custom.” On the day of the Shraddha, which is centred on sacred rites and rituals, a strictly vegetarian meal cooked without alliums is the mandate. The fish-laden feast follows after.

The custom, however, is not so much sanctioned by religion as it is predicated in the community’s cultural ethos. In Bengal, a region rich in fluvial resources, fish is not only a prime source of sustenance, but also a cultural touchstone of immense sentimental and symbolic significance. Fish is ubiquitous in the region’s cultural expressions. It is traced into ornate motifs of alpana, a form of folk art drawn on floors and thresholds in Bengali homes during auspicious ceremonies. It is also immortalised in verse and lore as a veritable metaphor for Bengaliness.

During weddings, after it has been beautifully embellished to resemble a bride, fish is sent to the bride’s home as a symbol of impending prosperity. It is also offered to the

gods and is even coveted by Bengal’s native ghosts. In the Bengali imagination, fish represents plenty and fertility, transformation and regeneration. It only seems apt that a morsel of fish should translate to the symbolic return to life.

As in Bengal, in the Mithila region of northern India, comprising fertile alluvial plains crisscrossed by numerous rivers, fish is passionately cherished. Among some sections of Maithili people, serving fish and rice is mandatory at the end of funeral rites. A similar post-funerary tradition of commensal eating of fish also exists in riverine Assam. Here, it is “called matsya sparsha (touching fish) and cooked soul [sole fish] is offered on that day to the departed soul,” writes scholar and folklorist, BK Barua, in his essay "Fishlore of Assam."

Such traditions are perhaps rooted in the bereaved person’s sense of identity as part of a community yoked by common beliefs and rituals, whether religious or cultural, which often shape the experience of bereavement. Food and shared culinary rituals, both literally and symbolically, offer a sense of solidity, familiarity and structure in the face of the elusive tenor of grief. Food, as succour and nourishment for the grief-ravaged body, a tactile tether in the face of the abstract, or a connection to lost loved ones, is crucial to mourning itself.

For communities across India and the subcontinent, the sharing of food—by way of opulent feasts or charitable feeding—has been central to the rituals of mourning and, all importantly, moving on. The food served at these tables often reflects cultural intricacies, regional affiliations and religious stipulations, which perhaps reinforce the sense of community within which the bereaved seek comfort and support. The Parsis, a small community descended from Persian Zoroastrians who arrived on the subcontinent to escape religious persecution, abstain from meat during their threeday mourning period, following a death in the family. On the fourth day, the end of the mourning phase is marked by a meal shared between friends and family, comprising dhansak—among the best known Parsi preparations outside the community.

Dhansak is a spirited, slow-cooked preparation made of assorted lentils, a medley of vegetables and mutton, flavoured with a complex blend of spices called dhansak no masalo. Always served with Parsi brown rice and mutton kavabs, dhansak may be served in restaurants and appear on Sunday lunch tables in Parsi homes, but it is never on the menu at joyous occasions.

The Kodavas of Coorg, in southern India, observe Madha on the 11th day after bereavement. This culminates in a feast that celebrates the life of the deceased, where all kinds of meat, especially pork—the mainstay of Coorgi cuisine—and alcohol is served.

“A must on this day is the paruppu payasam, a sweet dish made with moong dal, jaggery and coconut milk,” said Radhica Muthappa, a culinary entrepreneur from the region. Pudding, symbolic of joyous occasions, perhaps denotes renewal.

Author Thressi John Kottukappally tells me about the funeral traditions of the Syrian Christians native to the Kottayam region of Kerala. During the traditional postfuneral memorial service organised on the 30th or 41stday of a death, Kottukappally tells me, platters of rice balls and a bowl of cumin seeds are laid out.

“At the end of the service, it is mandatory that everyone in the congregation eats a few cumin seeds,” she said.

The rice balls are served as part of a stridently nonvegetarian Sadya—a traditional meal served on banana leaves—that follows.

“A binding feature of this meal is a dish made of a mix of curd, rice and bananas sweetened with syrup [made] of palm toddy sap—ingredients intrinsic to and representative of the region’s culinary traditions—that is served at the end,” Kottukappally said.

“Across the pond in Sri Lanka, visitors dressed in white deliver food to the mourners and the monks. The Buddhist ceremony, Daane, involves eating parupu (dal), kiri bath (rice and coconut milk) and gotu kola sambol,” writes Shylashri Shankar, in her book Turmeric Nation: A Passage Through India’s Tastes.

Among Tamil Brahmins, the food served at funerals is strictly vegetarian and panders to certain specificities.

“For instance, chilies are never used in the food served at funerals. Pepper is used instead,” Chennai-based writer Janaki Venkataraman said. “Neither are vegetables like carrots, potatoes or cauliflower.”

It isn't a mere coincidence that all these ingredients are not native to the subcontinent. They only arrived a few centuries ago and are yet to be incorporated into the more orthodox traditions of ritualistic food that seek validation in antiquity.

“The typical menu at a Tamil Brahmin funeral comprises simply seasoned curries made with vegetables like raw bananas, banana stem, string beans, broad beans, bitter gourd, etc., a simple rasam made with tamarind, ginger, pepper and curry leaves, plump vadas, etc.,” Venkataraman says.

Besides, there’s a tradition of offering a set of five sweets and savouries called bakshanam. Appalam (papad), perhaps because of its association with joyous feasts, is avoided.

“But most importantly the menu features at least a few items that the deceased was particularly fond of,” Venkataraman said. “The same dishes are prepared on every death anniversary thereafter.”

On the day of my grandmother’s shraddha ceremony, a plateful of food cooked by my mother and aunts in our family kitchen, was placed in front of her photograph. I helped them with the little things—fetching this and washing that. I performed every chore with earnest enthusiasm. After all, it was the closest I was ever going to get to cooking for my grandmother. However, this meal featured none of the rich curries, deep-fried breads or luscious sweetmeats that the guests were served.

Instead, there was bandha kopir chhechki—a light dish of cabbage and green peas stir-fried together, kanchkola bhaja or sautéed raw bananas and borir jhaal or sun dried lentil dumplings, deep-fried and cooked in a thin mustard gravy. The carefully planned menu was diabetic-friendly since my grandmother had been diabetic for years. When my cousin pointed out that the spirits weren’t likely to be diabetic, he was reprimanded for being “oversmart” and impudent.

In retrospect, I wonder if the composition of this meal was intentional, or if it was a reflexive attempt at holding on to the familiar and the tangible. As Shankar writes in her book, “A ritual, whether it is a religious one or something you have made up, helps to restore a sense of control to the mourner, control we have lost in the unexpectedness and the suddenness of the tragedy. A ritual involving cooking returns that control to you…”

In some Adivasi cultures, the ritualised act of cooking for the deceased is woven into the formal expression of grief. For instance, in his essay, Barua writes about an old custom among the Garos, a community of hill tribes spread across parts of Northeast India.

"On the morning after the cremation of a Garo man or woman, the widow, widower or a near relation of the deceased, goes to the place of cremation, with a cooking pot, some rice, freshwater prawns and an egg," he writes. "These are cooked if possible, on the embers of the funeral fire, and when the food is ready, the mourner breaks the vessel containing it and raises a loud lament.”

This practice is embedded in Garo mythology where the ghost of Megam Airiipa, the first man to die, returned to his house to find his wife catching prawns. Rice represents the food of the living and the egg represents a fat pig eaten at a funeral.

Hindu liturgy, on the other hand, decrees the offering of pinda—balls made of rice, sesame, jaggery and other ingredients—to the departed soul, not only as sustenance but also as a temporary body for its journey to the ancestral realm. Such cryptic rituals often explained in lofty philosophical and religious terms are, more often than not, grounded in the humble desire to connect with the deceased in the ways of the living. The practice of leaving food for the soul or making edible offerings to ancestors, or serving up the deceased’s favourite food at feasts thrown in their honour, also underscore this sentiment. In many Bengali homes, on the day of Matsyamukhi too, a portion of the fishy spread is left out in the open for crows. This is done in the hope that the deceased soul would inhabit the body of a crow and eat the spread.

I don’t remember though, if the platter of plump paturi, crisp topshe fry and the other fishy delights we savoured that afternoon in my grandmother’s honour, had been left out for her soul on the terrace somewhere. I don’t know if my grandmother liked fish at all. I had never seen her eat fish. After her husband, my paternal grandfather, died, my grandmother, an inveterate conformist, insisted on a strictly vegetarian diet, as was the norm among upper caste Hindu widows. Our family took comfort in the fact that it was a choice she made.

“What can we do? She won’t listen.”

But for generations of widows in Bengal, giving up fish was not a matter of choice. While the rest of their husbands’ families purged themselves of impurity and grief with morsels of fish, for them there was no Matsyamukhi.