6 minute read

The Writer’s Eye with guest author Ron Cooper

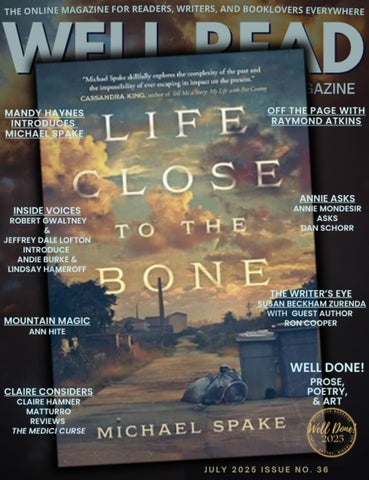

THE WRITER’S EYE with Susan Beckham Zurenda and guest author, Ron Cooper

Some months ago, I met author Ron Cooper and his wife Sandra when Ron and I gave presentations at the Georgia Writers Museum Writers Retreat. Ron and Sandra are instructors at The College of Central Florida, and having been an English teacher myself for over three decades, we connected in discussions about the teaching life and the writing life, too, of course, over dinner. This month Ron gives us a twist on finding inspiration in unexpected places. Rather than the unforeseen, Ron illustrates how subjects we know well can unexpectedly inspire us:

Fiction writers must negotiate a number of contrasting demands, such as being the champion of grammar versus being a surprising stylist, presenting logical plots versus avoiding cliched storylines, and writing what you know versus getting out of your comfort zone. My focus here will be on the last of these contrasts and how the inspiration for my first novel (and in many ways my others) grew from drawing upon things I knew but trying to recreate them in unexpected ways: professional wrestling, philosophy, and a knife.

My only interest in literature when I was a teenager was in writing (horrid) poetry, because I thought poetry might attract girls. I planned to become a physicist and never read novels, even those for which I wrote book reports. My life changed in high school Honors English, taught by a young, not-yet-jaded teacher who assigned us quite a heavy reading list. I took the class only because I thought an honors course on my transcript might impress a college admission officer.

One novel hit me like a mule kick (of which I have first-hand experience!), Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. The story is about impoverished, backwoods, uneducated folks, in other words, my people! I had thought, as far too many people still think, that the proper subjects of literature are upper class New Yorkers who fret about their investments, not poor peckerwoods who worry about hookworm!

I explored the work of other writers of similar ilk, such as Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, and later on Barry Hannah and Harry Crews. Although I took creative writing classes as an undergraduate, I also developed a deep interest in philosophy. I was on my way for an MFA in creative writing, but at the last minute I decided to enter graduate school in philosophy and have all the great questions answered.

Even as a philosophy grad student, I made notes for a novel about the things about which I knew something. The problem was that these things did not jibe well: philosophy and professional wrestling. I spent endless hours watching wrestling with my father on the weekends, and although I knew that those antics were scripted, I saw early on that the matches were passion plays of a sort, dramas pitting the most primal of human drives against each other. Why, I wondered, had authors not examined this art form for its fundamental lessons in human nature?

When I did my graduate work at Rutgers, a young adjunct instructor had just published a successful novel that had been labeled philosophical. I collared her in the hall and told her about my idea for a novel in which academia and professional wrestling collide. I explained that scholars presenting papers at philosophy conferences often seemed to sport the same bravado as pro wrestlers, so having them become entwined in the same arena could provide considerable laughs.

Lucky for me, she was a kind and patient person. After I gushed for a spell, she politely told me that after several unproductive starts, she turned to topics that she knew well, in her case philosophy and Orthodox Judaism. She said authors need to be masters of their work, and that means in large part that they are fully informed regarding their subject matter. If pro wrestling and philosophy are my expertise, then that should be my novel.

After grad school and numerous philosophy articles and conferences, I finally wrote that novel, Hume’s Fork. All through the process, an image stuck in my brain like a stinger (apologies to Flannery O’Connor)—a hunting knife owned by a family friend. He belonged to my father’s hunting club and owned a Randall Made knife that was the envy of all the club’s members. When someone asked to examine it, he’d make a show of hemming and hawing about this precious knife and how not everyone was worthy of hefting it, as he handed it over. That knife came to represent something, perhaps like T. S. Eliot’s notion of an objective correlative, about my growing up in the swamp that I still cannot quite put into words.

The knife didn’t make it into that first novel (nor any of the others so far) except in the sense that it was the symbolic instrument for extracting “what I know” from the dank recesses of my psyche. Today I am the proud owner of a Randall Made knife, and it speaks writing to me as much as any image of a book or pen as it gleams beside my laptop. (Perhaps you sense the effort it takes me to avoid slicing out puns like “honing my skills,” “being on the cutting edge,” “carving out ideas” and a sheath-full of others.)

So, I hope that you will benefit from following the old chestnut to write what you know. Try fishing something from your dusty memories that means something rather ambiguous to you and helps you to explore those things that you know but did not seem significant to you. But if you write a story that features, instead of Chekov’s gun, a Randall Made knife, I’m coming for you!