13 minute read

John M. Williams interviews William Walsh

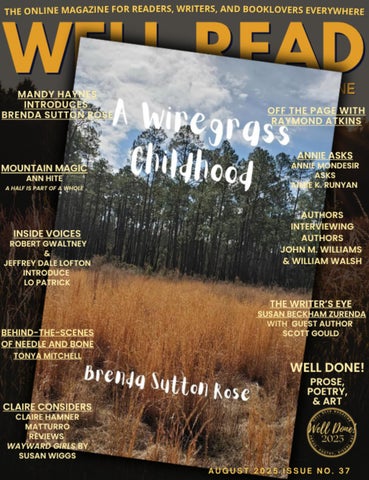

William Walsh’s new novel, Haircuts for the Dead, published by Mercer University Press, will be released on August 5, 2025. The following interview with John M. Williams was conducted on June 2, 2025.

JW: Why don’t we start with a brief history of the novel’s composition?

WW: I began writing this novel in 1988. It started out as a comedic novel about a woman I was working with. I wrote about 300 pages. The main character was named Paula and was nothing like Hannah. I wrote the story for the wrong reason, but things morphed, and I ended up changing her name to Hannah because it’s a biblical name. I started developing the idea of who she was and why she was the way she was, and then I started eliminating things from the original story. I made Hannah younger by about six years, and then I just got this idea about the fall of man.

JW: What’s the significance of the biblical name?

WW: I had the idea that she wrote down a Bible verse on a piece of paper, and from there I started developing the idea that here’s a young woman who has lost her religion but not her spirituality. She leaves the church and organized religion but she can’t leave the spirituality that’s inside of her. The book has a biblical sub theme.

JW: Would you say it’s a coming-of-age story?

WW: It is very much so for Hannah as a character because she starts out with this little rinky-dink job at the Cute Curl Salon. It’s a job that provides her economic freedom even though she is barely squeaking by. Traditionally, women have been economically dependent upon men. It’s not as true these days, of course, but it was up until the mid-1970s, even into the ‘80s. I gave her that job and then it just started developing—who she is, what she’s doing, why she’s doing things, the foundation for things to come. She thinks she’ll meet a man and get married, but of course, that apple cart gets completely tipped over because, at least in Hannah’s family’s life, pretty much the unthinkable happens: she falls in love with a black woman. Now you have this biracial lesbian relationship.

JW: You got it into an age where the relationship wouldn’t be that shocking.

WW: You’re absolutely right; society has, for the most part, grown up. I think the crux of the story now is Hannah coming of age by standing up to the bigoted, racist past of her family and the history that has permeated the family farm, and of course, losing the farm is essentially being cast out of Eden even though her father gets all that money. That’s sort of the class of Hannah’s family—they’re uneducated racists, and there are some things they do that are good, but they still don’t like anyone who’s different than them.

JW: That makes me think of Darnell’s first wife. Is that a piece of poetic justice?

WW: Yeah, Melanie Carlyle. She’s very light skinned but she’s Black, which he didn’t realize when he married her. So here’s this racist who goes to meet her family for the first time—you talk about irony. And think about what he does his whole life: he doesn’t work, he doesn’t have a job because they will garnish his wages, and he doesn’t want anybody finding out that he married a Black woman, so you know he’s not a good person, yet out of the marriage to Lilith you have this wonderful young woman, Hannah, who’s just trying to make it on her own.

JW: I wanted to ask you about the time frame. You started on this a long time ago but the “now” of the book seems to be our now, 2024-2025. Did you push the time forward?

WW: I had to. It took so long to write. I mean, everything was so different in 1988 when I started. We didn’t have computers, e-mail, cell phones with text messaging, all this stuff, so every time I would rewrite the book or work on it, it might be three or four years later, then all of a sudden it’s 10 years or 15, and I kept updating it, and then in 2022-23 when the book was really close to being finished the way I wanted it, it took another year to fine tune it, to update things in the background.

JW: Let’s talk a little bit about point of view. You could have written the novel completely as the Document of Life in first person, but you chose to use third person, from Hannah’s point of view as well.

WW: What happened was, I wrote the original story in third person, and then when I rewrote it, I just started completely over in first person. I rewrote 300 pages in first person and then one day, years later, I re-read it and completely rewrote the whole novel back in third person. Six months later, after I was done, I’m going down the road and all of a sudden I just get this idea—No! It’s wrong. I rewrote the whole thing again in first person. But somewhere along the line I realized that Hannah couldn’t have knowledge of everything. I realized I needed to have this second narrator who was omniscient. So now I have this narrator telling the story and then the story gets interrupted with Hannah’s Document of Life, or if she has a thought for a Bible verse, all of which is inserted into her narration. And that all probably took 12 years (laughing).

JW: There are certainly many examples of situations Hannah couldn’t have been privy to. I’m thinking especially of Dave Edwards towards the end, manipulating things unknown to Hannah.

WW: In fact, that’s one of the last things I wrote because Dave Edwards is this mysterious character who if there’s a character that is closest to me personally, that would be Dave Edwards. He’s sort of her knight in shining armor that she doesn’t know is in the background pulling strings. Hannah cuts his hair every three weeks; he’s a nice guy but he has an ominous past, unknown to the reader, although the reader sort of figures out at the end that this guy has a way of getting things done. I hope it comes out that you realize who murdered Hawkshaw Bales.

JW: Maybe we could touch on that now, because you set it up that it’s Margaret—“don’t you worry about him, I’ll take care of him”—she’s got the gun and is an expert marksman. The cops seem to think it was her. I was wondering why you left it unresolved.

WW: I truly didn’t think I left it unresolved. I did not want Margaret to be the murderer even though Margaret has skills and she’s angry and she even says “I’ll take care of him”—but she’s not the one that kills Hawkshaw. The reader has to look carefully at the end. Truthfully, the most important legal aspect toward the end is Hawkshaw Bales suing Hannah for paternity, and that leads to the motive for his murder.

JW: That was another question I had—his obsession with getting the child. But the rape is so violent—

WW: You want to know something about that? The brutality is in the description later of what happened, not in the physical act.

JW: Yes. To me, there are three really powerful scenes in the book: the opening scene of the baby and the burial; the second is the rape—the first time we hear of it it’s already happened; and the third is the murder of Hawkshaw. You dramatize neither that murder or the rape in the book.

WW: It’s not gratuitous. You want to know who taught me this? Harry Crews.

JW: Don’t show the violence?

WW: Yes. I was down at the University of Florida in Gainesville back in 1988 interviewing him. He was scary as hell, but he was incredibly nice. We talked about this very thing: He told me, “Understating something is more powerful than gratuitously describing it.” If you notice, that was true of the rape scene—not the baby scene but the rape scene. It is not seen but reported—so everything that happens is happening in your mind. You’re imagining it and it makes it more powerful.

JW: Like Hemingway. Anything you know, you don’t have to say.

WW: Yes.

JW: I wanted to ask you about the Sarah story. Where did you get the idea for the diary of a pioneer woman, and what was your rationale for entwining it with the main narrative?

WW: There was a real diary that was found somewhere out west. This was back in the late 1980s. It’s a true story—these people found an old handwritten diary in the rafters or somewhere from a woman who left from somewhere back east. They got it published and I read it and thought, I’m going to make up my own. I created a storyline where this woman has a husband and three or four kids and is basically his property. It was her plight as a woman that he controlled everything. He controlled the purse strings and even when she wrote letters for people for a couple of pennies, he took the money. Her journey parallels Hannah because Hannah’s on her own hero’s journey. She’s enthralled with Sarah and her story and becomes empowered and inspired by Sarah. In Sarah, Hannah sees similarities to her life, but more so to her mother’s life. When Hannah reads about Sarah’s life, she wants her own life to be better than the life her mother had. Hannah’s mother—Lilith—and Sarah are the same story, just one hundred and fifty years apart. Of course, that story is the antithesis of Hannah, who has options: she cuts hair to earn her own money; she’s scrappy; she’s trying to make extra money cutting hair at the funeral home; and what does she end up not having? What is it she doesn’t need in her life? A man. And it’s not by any conscious decision but then she simply falls in love with Margaret and so she doesn’t need a man in her life.

JW: Thinking about theme, I like the scenes when Hannah goes back to the farm because the older you get, the more loss becomes a theme of life, and she’s dealing with loss at a pretty early age: all of her past, everything she experienced as a child, was there, and the cutting down of the apple trees, that’s very symbolic.

WW: Yes, it’s just out of the Garden of Eden. What’s interesting is, part of the reason for cutting down the orchard and destroying the farm comes from David Bottoms because if you go to Canton to where the Kentucky Fried Chicken is, that’s exactly where David Bottoms’ house was. Years ago when he grew up, it was just a one lane road, and now it’s four lanes or whatever, but across the street was his grandfather’s farm, the family general store, the dog lot, the horse run, everything right there and all that land was David’s grandfather’s, and sometime in the early 1980s, after his grandfather died, it was all sold. Developers tore it down and built a Kmart. It’s all gone. Today, I go by there several times a week on the way to the university, and that’s sort of what’s happening in the novel. Although the farm isn’t completely buried under, it’s on the way. Hannah’s family farm was purchased for a new airport, but then they realized they didn’t have enough land—dumb mistake—and they sold it off. That part is based off a real event.

JW: You mentioned that Madison Jones read an early draft of the novel.

WW: Yes. By the time he read it, I was on my way to understanding the story and Hannah. Madison was quite wonderful in that he gave me some great insight. Like his novel A Buried Land and the Tennessee Valley Authority damming up the river and the two guys burying the woman under all that water, which is really kind of where Dickey gets his idea in Deliverance, it’s this whole idea of everything can be torn apart, torn down, rebuilt, and something is always lost. We bury everything and forget about it. This whole idea about a buried land resonated for me for all these years. He gave me the greatest advice when he said “I always have a character who is outside the law”— which, for me, is Hawkshaw Bales. I learned a lot from Madison.

JW: I believe you told me the opening chapter benefitted from the novel’s long period of gestation.

WW: Yes, the opening chapter is a powerful scene and one of those things that influences Hannah’s entire life. The reader begins to see how and why she is who she is. Chapter one was the last thing I wrote. I had undergone some reservation about the opening of the novel. I didn’t know what the problem was, but my instincts kept saying that something was amiss. I set the book down for nearly a year and simply thought about the story day after day. One day I was driving down Roswell Road with my mind not on the book. I was trying to survive Friday afternoon traffic. I was about three or four miles from my house when all of a sudden, BAM! I remembered the scene with the baby. It was a true story I had heard about an incident during the Depression. There was this family who couldn’t afford another baby to feed and when the baby was born, they held the baby up and dropped it on the floor and killed it and buried it in the cornfield. They knew where the baby was buried, but in Haircuts Hannah does not know and never finds the grave. She’s always searching for the baby and for things from the past. When I remembered this story about the baby, I knew it would explain everything about why Hannah is how she is. It’s an absolutely essential scene. I drove home and wrote the chapter in about three days and then published it as a short story, “The Fishing Trip,” in WELL READ Magazine. After that, I made more tweaks and turned it into chapter one. One of the most important things is at the very end of the story when Hannah’s talking about Sarah’s diary and Sarah traveling from Pennsylvania out west. This is when the reader discovers the real name of the baby, because it’s what her mother whispers in Hannah’s ear—the baby’s name—and that brought everything full circle. What a burden on a six-year-old girl.