10 minute read

The Group: An Introduction

David Maskill, Specialist, Art.

The Group Show: Retrospective Exhibition 1927 – 1947 (Christchurch: The Caxton Press, 1947). Held in the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puria o Waiwhetū Collection. This unique auction provides an opportunity to view and acquire works by artists who were part of a burgeoning movement. The activities of The Group saw the emergence of a distinctive thread in New Zealand art; its early participants were united in their collective rejection of ‘chocolate-box’ sentimentality favoured in the art of The Group’s parent institution, the Canterbury Society of Arts. They looked instead to new trends in progressive artmaking, and sought to capture something unique to New Zealand. Some embraced modernist trends more radically than others, but they were all committed to a new vision for art. Reviewing those artists who participated in exhibitions by The Group reads like an art history lesson. During the early years of The Group in the 1930s, exhibitors included Evelyn Page, Robert Nettleton Field, Christopher Perkins, Rita Angus, Leo Bensemann, Louise Henderson, Olivia Spencer Bower, Rata Lovell-Smith, Margaret Frankel, Doris Lusk and Toss Woollaston. In the 1940s, they were joined by the likes of Colin McCahon, Douglas MacDiarmid, Bill Sutton, John Weeks and Russell Clark. These artists strongly influenced the development of New Zealand art from this time. The 1950s saw the consolidation of The Group as the primary platform for progressive New Zealand art; the number of exhibited works and artists increasing dramatically. Artists from outside of Christchurch began to exhibit regularly, such as Dunedin-based Frank Gross and Auckland-based Milan Mrkusich. In the 1960s, a younger generation of artists showed alongside their more established peers. Artists such as Tony Fomison, Philip Trusttum, Quentin MacFarlane, Don Binney, John Drawbridge, Tanya Ashken, Michael Illingworth, Don Peebles, Richard Killeen and Ralph Hotere were involved at this time. Despite the growing network of dealer galleries in the main centres, The Group continued to hold exhibitions into the 1970s. Newcomers such as Philip Clairmont and Don Driver exhibited their bold art alongside work by their older colleagues. The Group’s stalwart, Olivia Spencer Bower, exhibited a suite of linocuts in the final Group exhibition in 1977, forty-four years after her first showing with The Group in 1933. It is a delight to present many artworks by these iconic artists. It has also been a pleasure to produce a catalogue that references the strong design aesthetic of The Group. One of the distinctive aspects of their catalogues was the use of modern design and typography. This was especially the case from the mid-1940s when they were designed by Leo Bensemann, and printed by the Caxton Press. This aesthetic has directly inspired the design of this publication. We have also reproduced two classic New Zealand poems by Denis Glover and Charles Brasch, publishers and writers of the Caxton Press, to acknowledge the interconnections between the artists of the Group and their literary contemporaries. It has been a real pleasure researching this period in New Zealand’s art history, working with collectors, and hearing the stories of The Group artists and the work they produced. It is a joy to showcase works from this significant time in our cultural history.

David Maskill Specialist, Art david@webbs.co.nz +64 27 256 0900

Rita Angus Lake Wanaka by Neil Talbot

Colin McCahon Small Landscape by Julian McKinnon

Louise Henderson Abstract 4 by Molly Lawton

Evelyn Page Living Room by Olivia Taylor 26

46

50

62

Olivia Taylor

Innovative New Zealanders have long wrestled with the dichotomy of our country’s remote condition. On the one hand, Aotearoa’s profound isolation can be stifling, with a limited resource supply and small population. On the other hand, it is a place of aspirational freedom, with a permissive social culture and openness to creativity. The Group was an affiliation of individual artists who saw opportunity in exploring homebound subject matter and the psychological condition of inhabiting this part of the world. Exhibiting together from 1927-1977, The Group were grass-roots artists who produced works of whatever they saw fit and hung their own exhibitions. By self-managing, they unintentionally revolutionised the New Zealand modern art aesthetic and improved art accessibility.

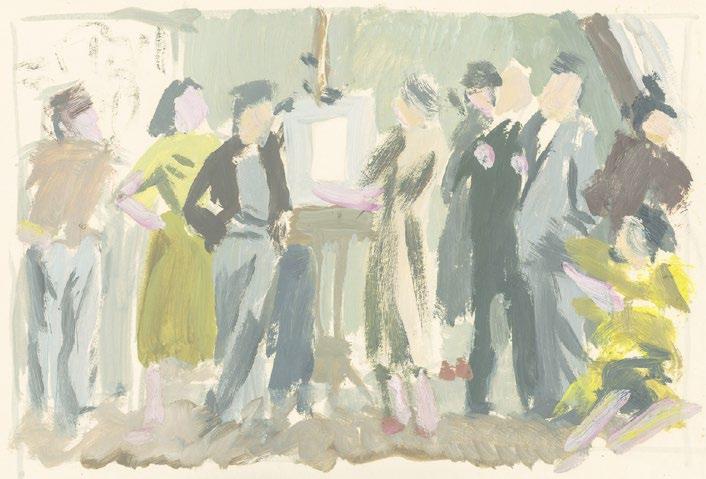

W.A. Sutton, Homage to Frances Hodgkins, 1951. Artist Bill Sutton, then a young lecturer at the art school, registered his protest at the rejection of Pleasure Garden by painting a large composite portrait of Hodgkins's supporters grouped around the work. At the centre of the image is Hodgkins and a young Colin McCahon. In the foreground, a discarded copy of The Press lies crumpled on the floor.

W.A. Sutton, Colour sketch for 'Homage to Frances Hodgkins', 1951.

1 Peter Simpson, Bloomsbury South, The Arts in Christchurch 1933 –1953. Auckland University Press. 2016. p. 3. 2 Ibid, p. 73.

3 Julie A. Catchpole. Thesis for the completion of the Master of Arts in Art History – The Group. University of Canterbury. 1984. p. 3-4. 4 Jill Trevelyan. Rita Angus – An Artist’s Life. Te Papa Press. 2008. p. 20 The Group first emerged in the late 1920s. This post-WWI period was a time of turbulence and social disruption, which led to considerable upheaval in the established frameworks within the arts. Established arts and literature societies evidently became more rigid, catering to conservative popular taste, and focussing on older styles of painting and writing. Consequently, fresh talent was often excluded. This created conditions in which young, adventurous artists and intellectuals had to carve out their own artistic space. The Group, which came to be the most prolific and enduring artist run initiative in New Zealand, started from humble beginnings in 1927. Graduates of the Canterbury College School of Art often gathered at the shared flat of Rita Angus, Leo Bensemann, Lawrence Baigent, and Archibald F. Nicoll at 97 Cambridge Terrace – near the Bridge of Remembrance of central Christchurch.1 Notably, the house was owned by Sydney Thompson, a leading post-impressionist painter, who invited the younger artists to live there. This ‘house of art’ became home to a circle of artists working in varying genres and styles, and an axis of the budding literature and visual arts scene in the south of New Zealand.2 The collective obtained a scantily furnished studio in Cashel Street, where founders Evelyn Page, Voila MacMillan Brown, Margaret Frankel, Ngaio Marsh, Edith Wall, and William Henry Montgomery invited new contemporaries to congregate for discussions and occasionally draw from live models. In 1929, the group of friends held their first show in the Durham Street Art Gallery of the Canterbury Society of Arts (CSA), which became the venue for the majority of their shows thereafter.3 Evelyn Page remembered it as “a social club for young painters who wanted to find somewhere to meet away from their Victorian parents.”4

5 Robert McDougall Art Gallery Publication. The Group 1927-1977 (November 1977. Issue 16.) Robert McDougall Art Gallery. Contribution by Leo Bensemann. pg. 11.

6 Robert McDougall Art Gallery Publication. The Group 1927-1977 (November 1977. Issue 16.) Robert McDougall Art Gallery. Contribution by Olivia Spencer Bower. p. 3.

Group Show 61 (Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1961) and The Group Show 64 (Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1964) retrieved from Christchurch City Libraries Heritage publications. Over the course of The Group’s long span as an artist run initiative, many New Zealand modern art luminaries were involved. Shows were always hosted in Christchurch, displaying works by artists directly from the city and around the country. Membership fluctuated, extending from the surrounding South Island centres of Nelson and Dunedin, and to the further reaches of the North Island. Notable members included Olivia Spencer Bower, Toss Woollaston, Robert Nettleton Field, Rata LovellSmith, Louise Henderson, Rita Angus, Leo Bensemann, Tony Fomison, Colin McCahon, Doris Lusk, Douglas MacDiarmid, Evelyn Page, Christopher Perkins, William Henry Allen, and William James Reed. The Group’s annual shows went on to become one of New Zealand’s leading forums for contemporary art. Even though The Group countered the stiff approach of established frameworks, it was not a collection of mavericks. The Group never had the objective of reforming or ‘shaking-up’ established galleries, art schools and art societies. Members simply wanted to make art their own way and exhibit it to their contemporaries. As well as being an active participant and exhibitor, Bensemann was also involved in the Caxton Press – which produced The Group’s show catalogues. He noted in his account of The Group in 1977 that it would have been impossible for the collection of individual artists to revolutionise the art establishments, due to the lack of uniformity and intention of its members.5 There was no committee, there was hardly a ledger, and finances were slim, meaning a hat was often passed around members to fund the shows. Sales were numerous, but for modest sums, therefore exhibitions often failed to break even. McCahon’s works would sell for only a few guineas, unfathomable prices by today's standards. Further reinforcing the idea that The Group was not revolutionary in its aims, members continued to exhibit and maintain memberships with other societies, such as the CSA. The Group’s shows in the early years even followed a similar format to the CSA. Openings were formal affairs. Dinner coats and glamourous dresses were worn by attendees who filled ballrooms adorned with primroses and offerings of lavish suppers.6

Leo Bensemann is pictured working at the Caxton Press, Christchurch. He started working for Caxton in the early 1930s and became a partner in 1937.

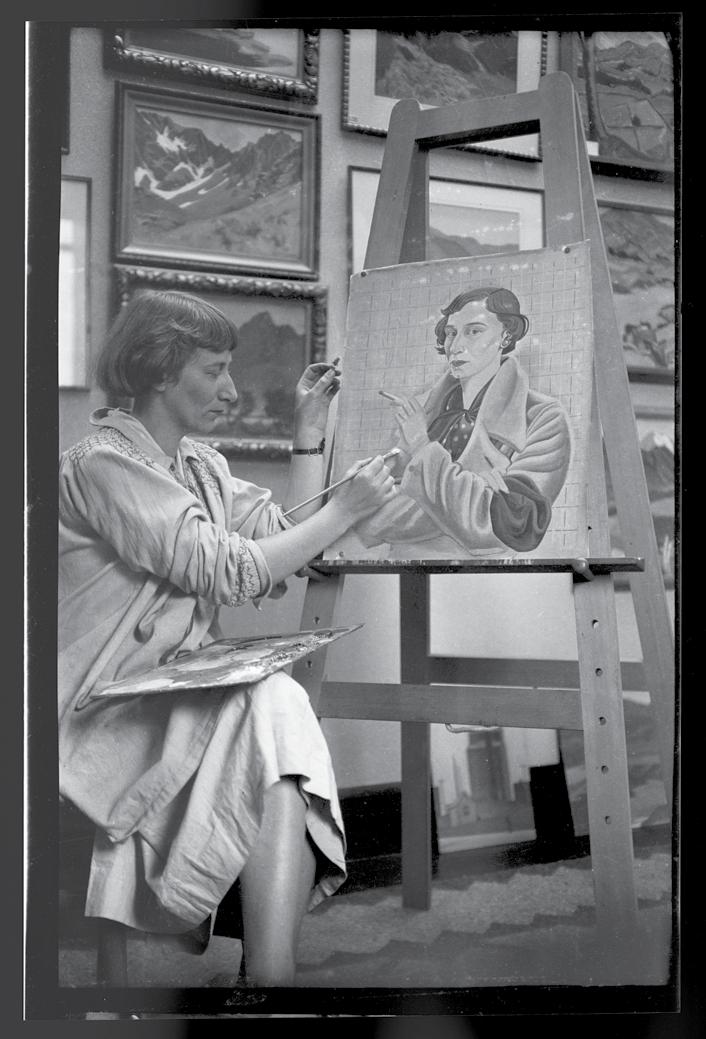

Jean Bertram, Rita Angus painting Self portrait, (1936 – 37), c1936.

7 Peter Simpson, Bloomsbury South, The Arts in Christchurch 19331953. Auckland University Press. 2016. p. 5.

8 Peter Simpson, Bloomsbury South, The Arts in Christchurch 19331953. Auckland University Press. 2016. p. 6.

9 Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. South Canterbury Artists: A Retrospective View 1990. 10 Ibid. The period in which The Group operated – from the late 1920s through to the mid 1970s – was a significant time for New Zealand social evolution. Established norms were questioned, and age-old repressions were mitigated to some degree. The Group is notable for strong female representation; women were founding members and active leaders who made up the majority. Diverse sexual orientation of members was accepted without prejudice. Further, many members embraced pacifism during the Second World War. Membership was largely drawn from those educated at the Canterbury College School of Art and their friends. Even with cyclic replenishment of membership over decades, most, if not all, members who flowed through The Group were Pākehā New Zealanders. Consequently, the prevailing attitudes of Pākehā were over-represented in the cultural output of The Group. Those attitudes were dominated by recent pioneering memory and economic conditions. Ideas of self-reliance, the challenges of surviving in New Zealand’s raw environment and weakening ties with Britain in the face of plummeting prices for export commodities were all factors. A broader cultural drive towards developing an authentic brand of national culture was in play, which ran in opposition to the shadow of identity cast by the rigid, industrialised, overcrowded mother country. Art production and subject matter between the 1930s and 1950s can be described as ‘nationalist’, borne out of a desire to create unique, idiosyncratic tropes that are akin to New Zealand’s national vernacular. Although The Group directly contributed to a nationalist aesthetic – with many depictions of raw landscapes in ochre tones contrasted with dramatic, icy, pacific blues – the term ‘nationalist’ was denounced by artists at the time; it carried connotations of the fascist movements that had engulfed Germany, Italy and Spain.7 The political liberalism of The Group and creatives of the inter-war and Second World War period advocated instead for the use ‘internationalism’. Twentieth Century writer and founder of the Caxton Press, Allen Curnow, preferred descriptions such as, ‘the condition of being a New Zealander’ to nationalist.8 Landscapes were a popular subject matter for members of The Group. Artists such as Toss Woollaston, Rita Angus, Olivia Spencer Bower, Rata Lovell-Smith, Doris Lusk, Margaret Frankel, and William James Reed rendered sparse lands that appeared to extend eternally past the frame. Reed spoke of his preference to paint the landscape in watercolour, stating that, ‘we are surrounded by fascinating landscapes of infinite variety.’9 He also spoke of The Group’s process of art making, stating that, ‘The Group believes that a well based technical knowledge of the fundamentals of visual art is necessary, but not of over-riding importance in the production of works of artistic merit. These exist to serve that faculty, not to drown it.’10 A common practice among members were excursions to the West Coast, the Canterbury High Country, and Mackenzie Country to paint, capturing light across plains and minimal emblems of settlement. Often, these paintings were made in modernist fashion, breaking the scenes down to basic forms and simplified arrangements of colours that celebrated the painting process. This approach to colour selection and application of paint was also adopted by those who painted portraits and still life works, such as Evelyn Page and Rita Angus.