7 minute read

THE STATE OF SUPPLIER DIVERSITY PROGRAMS IN CANADA

Paul D. Larson, Ph.D., CN Professor of SCM, University of Manitoba Jack D. Kulchitsky, Ph.D., University of Calgary Silvia Pencak, M.A., President, WBE Canada

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) includes “Diversity & Inclusion” among its Principles of Sustainability and Social Responsibility. Buying organizations are advised to “develop and implement practices that identify and develop supply management employees and suppliers from diverse and underrepresented populations.”1 Aside from its link to social responsibility, there is a business case for supplier diversity (SD). By encouraging competition and broadening the supply base, SD can result in better quality of purchased goods and services, as well as lower costs.2 This article presents selected results of a recent survey of Canadian buying organizations, on barriers, facilitators and motivators of SD in Canada.

While 31 percent of the survey respondents have full or “complete” SD programs, 44 percent have “limited” (initial or partial) programs. Elements of a complete program include supplier mentoring, tracking SD spend and focusing on both first- and second-tier suppliers. Limited programs have only gone as far as having a SD policy, training staff, joining a diversity council and/or including SD among their RFP criteria. Another 22 percent of buyers in the sample have no formal program but are guided by the principles of equal opportunity and anti-discrimination.

According to the survey, the three most important motivators of SD are aligning with organizational culture, bringing benefits to diverse communities and broadening corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs. Traditional performance indicators, such as reducing costs, increasing sales and profits or attracting investors, are among the least important SD motivators.

The top two barriers to SD – difficulty in finding qualified diverse suppliers and concerns about their ability to perform – imply a critical role for certification councils, such as WBE Canada and the Canadian Aboriginal and Minority Supplier Council (CAMSC). Leading facilitators of SD appear to be internal to buying organizations, e.g. presence of diversity champions and commitment of the leadership. CAMSC and WBE Canada are in the middle of the pack of facilitators. Interestingly, Supply Chain Canada, the nation’s premier purchasing/supply chain professional association, is the lowest rated facilitator by a substantial margin.

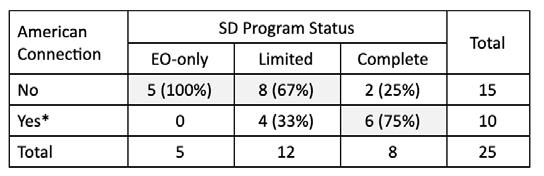

American connection and program status

At about 32 percent each, the respondents represent an equal portion of Canadian companies with no foreign (parent or subsidiary) connection and Canadian companies with an American parent. Another 16 percent of the respondents represent Canadian government buying organizations. The table shows a cross-tabulation of SD program status and organizational connection to the United States, as a subsidiary of or parent to an American company. Canadian organizations with American ties are expected to be closer to full implementation, since SD programs first emerged in the United States during the 1960s. “EO-only” organizations have no formal SD program but do follow the principles of equal opportunity.

*Canadian firm with an American parent or subsidiary Chi-Square (p-value) = 7.64 (.022)

All Canadian organizations in the sample with EO-only and 67 percent of those with limited SD programs have no direct American affiliation. Conversely, 75 percent of organizations with complete SD programs have some sort of direct connection, usually as a subsidiary of an American company. It is notable that all Canadian organizations with an American connection have either limited or complete SD programs. Organizations with larger spend (i.e. higher budgets for buying goods and services) are also expected to have more advanced SD programs. Large organizations command more resources required to create and administer programs. Survey results reveal that small organizations (those with less than $1 billion annual spend) are six times more likely to practice EO-only – and not have a SD program. On the other hand, large organizations are five times more likely to have complete SD programs. For more details about the survey results, and access to the full report, visit https://wbecanada.ca/.

Paul D. Larson, Ph.D. is the CN Professor of Supply Chain Management at the University of Manitoba. Paul is lead author of Supplier Diversity in Canada: Research and analysis of the next step in diversity and inclusion for forward-looking organizations, published in 2016 by the Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. Jack D. Kulchitsky, Ph.D. is a Senior Instructor in the Haskayne School of Business at the University of Calgary. Jack is the co-researcher on the 2020-21 supplier diversity project, which includes surveys of suppliers and buyers, along with a supplier diversity program content analysis of Canada’s “Best Diversity Employers” in 2020. Silvia Pencak, M.A. is the President of WBE Canada. Silvia is an innovator driving transformation in supplier diversity in Canada with projects like WBE Canada Toolbox, Supplier Diversity Accelerator, Supplier Diversity Data Services and many others, designed to enable and propel supplier diversity forward in Canadian market.

REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the survey findings presented in this report, along with the Supplier diversity literature, the following recommendations are advanced:

1. Government organizations are needed at the table

SD presents a great opportunity for diverse businesses thanks to improved access, added support and development. However, Canada is still behind in its implementation of SD at all levels of government. With all the focus on diverse communities, and internal (workforce) equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) initiatives, there appears to be relatively little tangible support for diverse businesses in terms of public procurement opportunities. Government organizations, universities and hospitals should ramp up their involvement, engage with more diverse suppliers, and report SD metrics, such as number of diverse suppliers and spend with diverse suppliers. Public-sector post- pandemic recovery efforts should include SD as a strategy to ensure long-term success of diverse communities.

1. ISM (2020), ISM Principles of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, Institute for Supply Management, Tempe, AZ, (https://www.ismworld.org/for-business/ corporate-social-responsibility/). 2. Bateman, Alexis, Ashley Barrington, and Katie Date (2020), “Why You Need a Supplier-Diversity Program,” Harvard Business Review, August 17, https://hbr. org/2020/08/why-you-need-a-supplier-diversity-program.

CANADA continued

2. Organizations should leverage the support of

Canadian certifying councils

The survey confirms the importance of the councils. Top barriers of SD program implementation (difficulty finding qualified diverse suppliers and concern about their ability to meet requirements) can be resolved by working closely with the councils to ensure that suppliers are developed, informed, and connected to supply chains. Councils also verify eligibility of businesses for corporate and government programs to ensure transparency and compliance of SD efforts. Councils, such as WBE Canada, provide support for the development of SD programs and connection to peer networks of professionals pursuing similar efforts in Canada and the U.S. enabling sharing best SD practices, idea exchange and facilitating improved programming.

3. Tier 2 reporting is needed

While the primary driver for SD programs in the US may be economic, this research shows that the primary driver in Canada continues to be social impact and company values. Reporting requirements could encourage more organizations to pursue SD – turning it from a “nice to have” to a “must have” initiative. While some procurement opportunities might be too large for diverse businesses, requiring first-tier suppliers to track and report their diversity spend (with second-tier suppliers) would contribute to more opportunities for diverse-owned businesses.

Supplier diversity could significantly impact the success of Canadian diverse businesses and positively impact their communities becoming an economic driver in a post-pandemic world. The authors encourage corporations and governments to consider implementing supplier diversity initiatives and report on the impact. For a full list of recommendations, and access to the full report, visit WBE Canada website here.

Strengthening our economy through supplier diversity Strengthening our economy Inclusive procurement practices strengthen local economies, forge new through supplier diversity business opportunities and create value for communities. That’s why we developed the RBC® Supplier Diversity Program in 2004. Inclusive procurement practices strengthen local economies, forge new Our goal is to advance equality of opportunity for women, BIPOC, LGBT+, business opportunities and create value for communities. That’s why we people with disabilities, service-disabled and veteran-owned businesses developed the RBC® Supplier Diversity Program in 2004. by promoting an inclusive supply chain and levelling the playing field for Our goal is to advance equality of opportunity for women, BIPOC, LGBT+, diverse suppliers. people with disabilities, service-disabled and veteran-owned businesses by promoting an inclusive supply chain and levelling the playing field for diverse suppliers.

Learn about our Supplier Diversity Program at