3 minute read

WATER IN THE WEST

from Water in the West

Faces Troubling Times

Advertisement

May, 2023

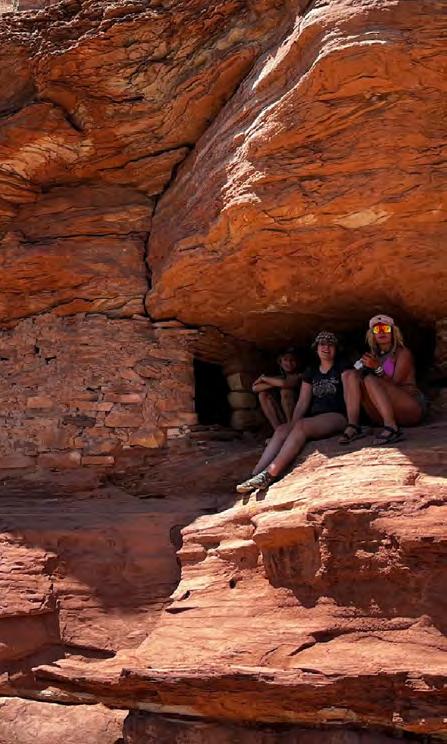

AsweeddiedoutoftheGreen River,wehoppedontoamuddy river bank and began our short journey to find the Anasazidwellings.Thetrailto the dwellings was slowly fading, making the rough Tamarisk scrape against our legs, leading me to believe that this trail was not used often. Chris Carithers, our teacher, led us through this dry sandy terrain in a single fileline.Icouldfeelthehot peoplewithinourlittlegroup, including myself, had to scramble back down the rocks to a place we had overlooked, andthere,hiddenbetweentwo rock ledges was an Anasazi dwelling. We rushed to glance at this small structure made with blocks of sandstone held together by mud mortar. Inside, the dwelling was dark with a smooth floor of loose sand. As I glanced up at this miraculousstructure,IknewI had to search for more. My mind yearned to learn more about what happened to the Anazasi,especiallybecausethe same disaster that destroyed them, now seems to be on the vergeofdestroyingus.

The Anasazi put extensive amounts of demand on an arid piece of land where, “"environmental resources weredecliningandpeoplewere livingincreasinglyclosetothe margin of what the environment could support” (Diamond,2005,P.156).This sand continuously plunging into my shoes as it gave way beneath my feet, giving me the creeping feeling that spiders might find their way into my shoes. After walking for a little while, we found our way to a light red and sandy-colored rock formation. As we climbed up this rock formation we heard a shout coming from the end of our line, someone had seen an Anasazidwelling.Acoupleof continued until the water was so sparse that the Anasazi could no longer cultivate the resources they needed to fuel theirsociety.Asscientistsand archeologists have looked into whathappenedtotheAnasazi, ithasbecomeabundantlyclear that creating thriving communities in the harsh environment of the American Southwest is immensely difficult. This is reflected in the problems currently facing theAmericanSouthwest. and many more are prime examplesofcitiesthatarenot able to survive without assistance. Like the Anasazi, these cities have flourished within an environment that is notcapableofsustainingthem. Theyneedloadsofwatertobe imported to keep their cities running.Thishasprogressively become more and more of a problem, especially with the drought that started back in the early 2000s. The drought has continued to gnaw at the edgesofoursociety,whileour demand for water is rising, causing the water to decline, leaving us with fewer and fewer resources to survive. This could ultimately lead to the destruction of our civilization, just like what happened to the Anasazi. So, wecandecidetofightagainst thisdroughtanduseourwater sustainably, but this would take everyone working as a united force which is not somethingwehavebeenableto accomplishsofar.

TheAnasaziwerebestknown for building spralling rock cities taller than any other city until the 1880s, when Chicago built skyscrapers (Diamond,2005,P.156).They also built a strong thriving community where they mastered architecture, made pots, and lived peacefully. However,thesepeacefulyears didnotlast.Theircivilization collapsed due to horrible things like drought, deforestation, and overpopulation. So, their society thrived and then abruptlydisappeared.

This leads us to a question that Heather Hansman, the author of Down River, asked. The question was whether, “"human behavior is able to change before we have to resort to building new technologies to fix human mistakes” (Hansman, Personal communication, May 22, 2023).

Hansmanhasalsogivenusways tosolvesomeofourchallenges when it comes to water management.Thefirstsolution she introduced was to change thewaythatwaterrightswork byputtinghumanneedsfirst.

Brad Udall, a climate scientist that Hansman interviewedsays,“"thatifhe could completely flatten the waterrightssystemandbuild it back up, he would put criticalhumanneedsfirst,the entireenvironmentsecond,and allotherusesinathirdtier. Forexample,you’renotgoing to grow alfalfa and not get water to Denver” (Hansman, 2019,p.194).Thisisimportant becauseifwedonotputhuman needs first our societies will start to crumble which would inturnmakenaturefallapart. Another solution that Hansman offeredwaslearningtomanage the basin as a connected systemthisway,“"watercould bemovedaroundtowhereit’s needed most” (Hansman, 2019, p.194).Thethirdsolutionthat HeatherHansmanprovidedwas finding a way to construct water management by conserving the water. She ascertainedthat,“"conserving canlooklikealotofdifferent things: water markets, leveling fields to maximize crop absorption, cutting energy use in cities, and finding ways to reduce reservoirevaporation,”areall things we should be doing to conserve our dwindling water supply(Hansman,2019,p.196). So, there are multiple ways that we can create a sustainableandevenequitable relationshipwithwater,butso far we have not been able to cometogetherasoneandfight forourfuture.

AsIcontinuedtoclimbthe twisting path formed on this red sandy-colored rock formation,Isearchedformore Anasazi dwellings. I rounded thecornerhopingIwouldsee an Anasazi dwelling. Sometimes,Iendedupspotting one and sometimes I did not, but every time I saw a little Anasazi dwelling tucked between a rock ledge, hidden from the outside world, I wouldbeoverjoyed.Ourwhole groupwouldagainrunrightup to the rectangular rock opening and look inside. We could have gone looking for Anasazidwellingsforhours andhours.Inmyexcitement, Iroundedcorneraftercorner, ignorant of how far I had come. This made me wonder how many corners we were going to round until we start conserving our water and overallthenaturalworld.Will we get swept away by ignorance and not take action to save our dwindling water supply? Or will we stop rounding corners and start to fight for our water, our nature,andourworld?

LELAH HERRINGTON