11 minute read

WATER WITH A HEART

When entrepreneur Kimberly Reilly (SLL’95) decided to develop a new, socially responsible business, she focused on the most basic of human needs: water.

Through her research, Reilly discovered that she could make a big impact by making clean water more accessible to people around the world. It was a way to make possible her dream to “uplift women and girls,” she says. Without clean water coming directly into the home, women and girls in developing countries spend hours a day carrying water. “It’s the biggest thing holding girls and women back,” Reilly says. “It keeps girls illiterate and women unable to earn incomes.”

Advertisement

Reilly teamed up with fellow entrepreneur Megan Hayes, her good friend and neighbor in Cohasset, Massachusetts, south of Boston. Together they created Everybody Water, launched earlier this year.

Everybody Water enables consumers to buy water in eco-friendly carton packaging—at the same time supporting water and sanitation infrastructure projects for the world’s poorest communities to transform lives. The company has teamed up with the nonprofit Water1st International, donating a portion of each purchase to the organization’s work.

Reilly and Hayes personally track the projects they support. Currently they’re helping finance projects in two communities in Honduras and next in Bangladesh. Getting water into the home is critical to a full solution, Reilly stresses. “When there are only hand-pumps in villages, women will still spend their time transporting water. We want them to have the resource of time to do other things.”

The water system and sanitation projects they fund use local engineers, contractors and merchants to plan, organize and build, so the impact on the community is sustainable.

“We are fortunate to live in bubbles where we can’t even imagine people have these struggles over something so basic,” Reilly says. “Everybody Water is engaging people on this topic when they are buying a carton of water— and getting them excited to be part of the solution in an everyday way.”

Everybody Water is already in more than 200 markets and major hotels in New England. Reilly has found that buyers are eager for an alternative to plastic and identify with socially conscious brands. The paper in the paperboard carton is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council; the cap is made from sugarcane. The carton is 100 percent recyclable. The water itself is sourced from a community system in Saline, Michigan, and is filtered by reverse osmosis.

“The Georgetown community is an inspiring group of mindful people,” Reilly says. “What I love is that the university is driven by Jesuit values across disciplines. It makes me proud that what Everybody Water is doing is aligned with those values.”

What do you get when Georgetown Athletics and Jack the Bulldog join forces with the Law Center, the Georgetown University Alumni Association and the Georgetown Entertainment and Media Alliance? An incredible Hoya road trip across the East and Midwest, bringing together alumni, parents and friends for exciting Big East Tournament basketball-watch parties, intriguing lectures and memorable networking happy hours.

In its premiere year, “Hit The Road Jack” brought Blue and Gray pride to Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago and Milwaukee, as the men’s basketball team journeyed to the Big East Championship. Along the way, alumni professionals in the fields of law and sports led thought-provoking panels and informal chats.

More Than a Meal

Noobtsaa Philip Vang (MBA’16) craved his mother’s cooking. It was 2014, and he had just moved to DC to start his MBA at the McDonough School of Business. He missed the taste and comfort of the Northern Lao and Hmong food that his mother made back home in Minnesota. There had to be a way for him to connect with a home chef in DC.

“The best meals are at someone’s house, where you see them cooking, putting love and passion into the food,” he says. Vang decided to take matters into his own hands. Inspired by the emphasis on social impact that he’d found at Georgetown McDonough and workshopped in his courses, he created Foodhini—a Washington, DC, online restaurant that connects immigrant and refugee chefs directly with customers.

Now in its third year of operation, Foodhini offers more than a meal. It focuses on “the power of food to create sustainable jobs and opportunities in communities of the diaspora,” Vang says. It’s a community he knows well.

Vang’s parents came to the United States from Laos as Hmong refugees after the secret war in Laos, a proxy war that was started when the CIA recruited Hmong soldiers to fight the communist Lao, which supported the Vietcong during the Vietnam War. His family settled in Minnesota, which is now home to a very large Hmong community. He grew up seeing firsthand the chal- lenges that refugees face in trying to start a new life. His parents had limited education and English-language skills and worked multiple jobs to provide for the family.

Vang praises his mother’s cooking, with a special shout-out to her “bangin’” egg rolls, but starting a food-related business centered around her food was wildly beyond his parents’ financial and physical means.

Vang came to Georgetown McDonough because of the location and its emphasis on social impact. “DC’s the epicenter of everything if you want to be in social impact,” he says. But Vang didn’t see himself working in a traditional business, let alone starting his own business.

“What caught me was the social entrepreneurship emphasis that I felt at McDonough,” he says. “You are surrounded by people who want to fix certain problems the world is facing. It’s a place where you can dream up how you see the world and its potential. You feel like everything is possible,” he says. “That’s what’s really special about Georgetown.”

One of the reasons Vang chose McDonough was the reputation of adjunct professor Melissa Bradley (B’89), who teaches impact investing and social entrepreneurship, among other topics. “I took her class as soon as I could take an elective,” Vang says. The structure of the course was fundamental to where he is today:

Bradley has students spend the class working on an idea that motivates them.

“It was a great place to try things because you are free to fail,” Vang says. “It’s a safe place.”

“Noobtsaa’s passion was obvious,” Bradley says. “His fond memories of his mom, coupled with his commitment to helping other immigrants in the food space, was clearly a competitive advantage for him.”

With the help of fellow MBA students, Vang rolled out the first iteration of the Foodhini concept at the annual Startup Hoyas pitch competition. Foodhini draws its name from “food” and famed entertainer Harry Houdini, who dazzled audiences with his stage performances of illusion and magic. Vang began beta testing in 2015 and continued throughout until he graduated in May 2016 and launched in the fall 2016 while a fellow at the nearby Halcyon Incubator. With no food or business experience, he worked his own magic and made Foodhini a reality. Operating first out of a shared commercial kitchen space in DC, he’s now in his own location with a catering-size kitchen in the back. “It’s grown into something I didn’t expect,” he says.

Here’s how Foodhini works: go to Foodhini.com, pick and choose the dishes you want from each of the different chefs, choose a delivery date and time and wait for it to arrive at your door. Vang currently has four chefs on his team who work in the Foodhini kitchen, making meals to order. Foodhini has a curated multicultural online menu. Customers order by 8:00 p.m. for dinner delivery the following day. Chefs cook dishes fresh every day and the menus are based on the foods of their home countries—Eritrea, Laos, Iran and Syria.

Vang admits to growing pains, including some humorous stories about his own cooking failures, but “we’re building a place that people feel proud of,” he says.

“Our chefs don’t come here just for the paycheck,” he adds. “They come for the meaning and the mission.

Vang’s primary role as CEO is to manage the high-level strategy and vision of the business: marketing, partnerships, fundraising, financials and growth. In addition to the online space, Foodhini also offers traditional catering and recently launched their first mini-restaurant inside of the Whole Foods grocery in Foggy Bottom, with more retail locations on the way. The business demand may soon create an opportunity for more chefs, and Vang works with local immigrant and refugee assistance organizations to identify potential candidates.

Vang says the inspiration behind Foodhini is his mother, who he believes could have been a great restaurateur if she had the resources. Now he’s giving others the chance she never had.

Lives Well Lived honors a few alumni who have recently passed away with short obituaries. We share with you these portraits of alumni beyond the headlines who have made an indelible impact living day to day.

You can find an In Memoriam list at alumni.georgetown.edu/in-memoriam

Cedric Asiavugwa (L’19)

If you were to glance at Cedric Asiavugwa’s appointment calendar, you would marvel that with his array of jobs and service activities he would have any time left for law school. Yet he was a top student and scholar and had been committed to a life of service since an early age. A third-year law student, he planned to return to his native Kenya to pursue a career promoting the rights of refugees. Tragically, his life was cut short on Ethiopian Airlines flight 302, which crashed near Addis Ababa on March 10. He was 32.

In addition to law school, Asiavugwa served as residential minister in New South residence hall and worked in the Office of Campus Ministry, where he offered everyone a warm smile and ready ear. He also was the assistant director of advancement for St. Aloysius Gonzaga Secondary School, a free high school in Nairobi for orphans living with HIV/AIDS.

Asiavugwa was a Blume Public Interest Law Scholar and a Pedro Arrupe Scholar, studying for a J.D./LLM degree in International Business and Economic Law. He also assisted refugee clients seeking asylum in the U.S. for the Center for Applied Legal Studies clinic.

He is survived by his fiancée and 1-year-old son.

Karen Anne Foley Kelly (B’78)

A trailblazer as an undergraduate business student at Georgetown, Karen Anne Foley Kelly (B’78) went on to work as one of the few female stockbrokers at Merrill Lynch in Old Town Alexandria, Virginia. There she met her husband, Michael Kelly, with whom she raised three children: Michael Jr., Mary, and Thomas.

“My mother was an original Mary Poppins, she was practically perfect in every way,” said Michael. “Every night she read aloud to us children, inspiring wonder and truth with magisterial delivery.”

Kelly shared her love of literature with several generations of children as a librarian at St. Mary School (now the Basilica of St. Mary School) in Alexandria. Starting out as a parent volunteer, she eventually became head librarian—earning her master’s degree in library science at Catholic University while working full time.

Kelly’s faith and her joy in the beauties of life sustained her through her battle with cancer. Surrounded by family, she passed away on March 16, 2019, at the home of her brother Dr. John Foley and his wife, Dr. Lakshmi Vaidyanathan. She is also survived by her mother, Eileen Foley, her siblings Thomas and Jeanne and their families. Her father, John P. Foley (C’53), died in 2018.

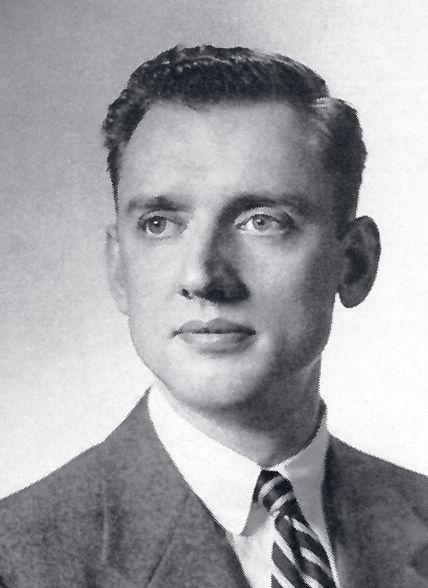

Arthur Bernard Calcagnini (C’54)

Over the years, Arthur Calcagnini (C’54) and his beloved wife, Nancy, received thousands of thank-you letters from the Hoya community expressing gratitude for the couple’s extraordinary gifts—particularly for undergraduate scholarships and the Office of Mission and Ministry.

Committed to the principles of Ignatian spirituality, Calcagnini frequently spoke with students at the retreats. In 2013, he fulfilled a dream with the completion of the Calcagnini Contemplative Center, situated on 55 acres in the Blue Ridge Mountains. “Part of this story is not only the transformation of the students, but the transformation of the giver,” he said.

A recipient of Georgetown’s John Carroll Award in 1994, he served on the university’s Board of Directors, Board of Regents, and Board of Governors.

“Arthur’s legacy will thrive in and through the Campus Ministry programs he endowed, the retreats he supported and the gorgeous mountaintop campus he made possible. He will remain a key part of Georgetown’s commitment to being a Catholic home for people of all faiths,” said Rev. Mark Bosco, S.J., Ph.D., vice president of Mission and Ministry.

Calcagnini died on June 12. He is survived by Nancy, his children Arthur III (C’85), Christina (L’93), Regina (L’94) and Victoria (Parent’05), as well as 12 grandchildren.

George A. Tralka Sr., M.D. (C’49, M’56)

Dr. George Tralka spent most of his career practicing internal medicine in Vienna, Virginia. “He was an old-fashioned doctor,” says his son, George Jr. “When patients came to see him, first he would just talk and listen and ask questions.”

After retiring from his practice, Tralka finished his career in civilian health care at the Pentagon—coming full circle from his World War II military service. At age 17, Tralka had signed up for the Army Specialized Training Program and went on to serve in the 103rd Infantry Division in Germany and Austria. Setting his sights on Georgetown following the war, he hitchhiked from his hometown of Amsterdam, New York, to DC to visit campus.

Tralka had many interests, including drawing satirical cartoons, which appeared in his undergraduate and medical school yearbooks. Even as he got older, he “didn’t like to sit still or stop reading or learning,” says George Jr. “He was fabulous with technology,” he adds, noting his father’s attachment to his iPad and Alexa and the films he’d make of his global travels.

Tralka died on May 14 from pancreatic cancer. He was predeceased by his wife, Judith.

In Transition

by Madeline Vitek Memenza, Associate Director, Campus Ministry

If there’s a thread in the work that I have done at Georgetown, it’s been working with students through transitions in their lives, which has been a fascinating lens through which to view the Georgetown experience.

In my first six years here, I worked exclusively with firstyear students. I ran a residence hall, and then I ran the Escape retreat program, a nondenominational overnight getaway for first-year and transfer students that provides a time for reflection. Our retreats are at the beautiful Calcagnini Contemplative Center about an hour from campus, which really gives a sense of being away.

We focus so much on the Georgetown experience while students are having it. But Escape explores what it means to transition into Georgetown. Now I run our senior retreat, and I am spending a lot of time thinking about what it means to transition out of Georgetown.

The senior retreat is fantastic. It’s another liminal space. Students have just finished their last semester and last finals but they haven’t graduated yet. It starts on a Sunday evening as senior week is about to begin, which is incredibly fun and exciting, but I think it ’s also hectic and stressful in its own way.

About 60 to 70 students attend the senior retreat overnights. They introduce themselves and say what they study. But really, it’s already “studied” because it’s done now. I remind them that they are done being undergraduates. There can be some groans around the room and, of course, excitement. The retreat asks them, “What are you going to carry with you from Georgetown? What is going to last?”

What are you going to carry with you from Georgetown? What is going to last?

What is the experience of seniors as they graduate? You’re about to go into a world where Georgetown’s emphasis on cura personalis , on reflection, on the value that who you are is just as important as what you do. These values may or may not be present in the space you’re going to occupy after you leave. More likely, it will not be a central focus.

This transition is a significant part of students’ Georgetown experience, not separate from it. We often hear from alumni who share that they didn’t realize what it meant to leave Georgetown. They are working in a liminal space—the “in-between” space—of “Who am I as I’m leaving Georgetown?”

For the most part, our students eat, work and play on and near campus. That’s their locus. Georgetown is an incredibly tight-knit community—it’s a specific and distinct culture, even in the higher-education space. Now they are moving all over the country—and internationally—and they are starting to think about what that means for the close friendships they’ve made here. They are thinking about who they want to be. What will they carry? Is it still an ability to listen and cultivate a sense of interiority even though they aren’t at 37th and O anymore?

Graduating is incredibly important for students. And it is also a time when they are starting over, very much like when they arrived on campus. It’s a big transition. What I love about Georgetown is that I get to accompany students over their four years of transition— what a privilege.