3 minute read

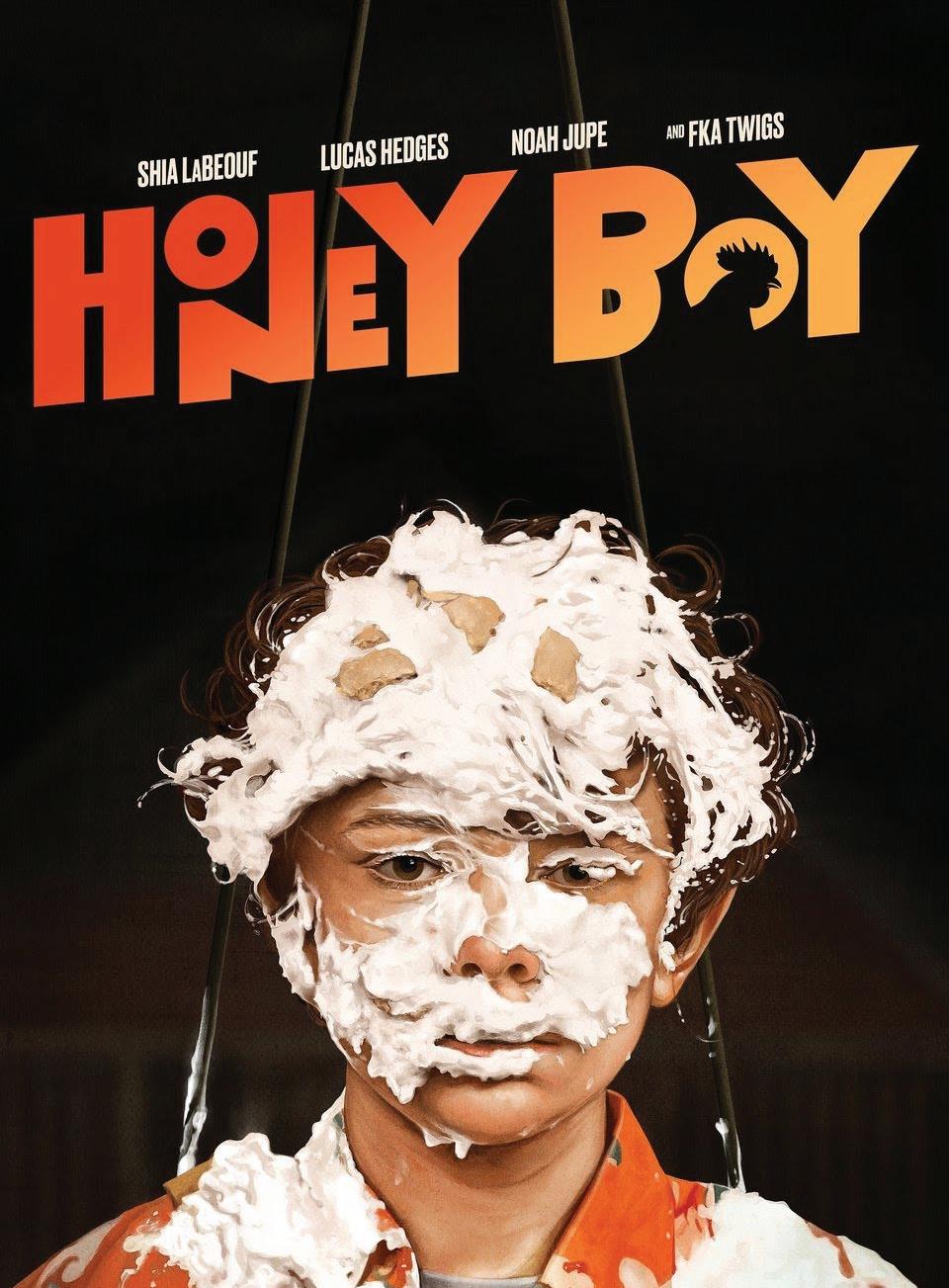

Honey Boy

Shia LaBeouf BY MACY HARDER

I don’t think I’ve ever felt so emotionally attached to a fi ctional character, let alone a 12-year-old boy, until now. Actor Shia LaBeouf doubles as a screenwriter in this semi-autobiographical fi lm, in which we gain more insight into his past of childhood fame, addiction, and mental health issues and into his relationship with his abusive father. His 12-year-old self, depicted as “Otis,” is played by Noah Jupe, who conveys an emotional maturity well beyond his years. Lucas Hedges also gives a strong performance as tThe young adult version of Otis, in treatment for substance abuse. And fi nally, LaBeouf takes on the part of his own father with an extremely powerful and cathartic execution of the role.

Advertisement

“Honey Boy” is raw, intense, vulnerable, and unlike anything I’ve seen before. It almost feels as though we’re intruding into the depths of LaBeouf’s psyche as we watch his trauma unfold on screen. Jupe’s performance of a young boy who feels alone in the world is brilliant and captivating, tugging at every single one of our heart strings. But at the same time, the fi lm has very few aspects of self-pity. Rather, it’s apparent that LaBeouf’s honesty in his writing and performance is therapeutic for the actor, maybe providing some sort of personal closure.

Above all, this fi lm served as an emotional release I didn’t know I needed. I connected with Otis as if his pain was my own. “I’m gonna make a movie about you,” he says to his father. As if for the fi rst time, I exhaled; this full-circle moment left me in tears on my living room couch. LaBeouf’s depictions of pain, longing, and other complex emotions in this fi lm are riveting, and “Honey Boy” is something I won’t forget for a long time.

Construction Time Again

Depeche Mode BY EVAN FERSTI

In one of the more fortunate events of 80s music, infl uential keyboardist Vince Clarke left the band Depeche Mode after recording just one album with them. While Clarke’s later projects would consist of mostly uninteresting synth-pop, Depeche Mode became free to expand their sound, and by incorporating industrial elements into their new wave style, they became one of the few bands of their type that could truly put on a stadium show. 1983’s “Construction Time Again” fi nds an early version of the band still transitioning away from Clarke’s infl uence.

The major theme of the album is, as the title suggests, the consequences of infrastructure development, with appropriately titled songs like “Pipeline” and “The Landscape is Changing.” This lends itself to political messaging, which, while not the band’s strong suit, is something they’ve certainly dabbled in over the years. For example, lyrics like “I don’t care if you’re going nowhere/just take good care of the world” are well-meaning but not particularly impactful. Elsewhere, “Two Minute Warning” is a lower-tier 80s nuclear apocalypse anthem, and while “Told You So” is memorable and employs interesting textures, it is also not particularly well-written. The album produced two singles, and while “Everything Counts” is a classic, “Love, in Itself,” which opens the album, features a goofy arrangement that isn’t particularly endearing.

Writing an album about a world dealing with major changes fi ts this era of Depeche Mode’s career well, as they were undergoing a major stylistic shift of their own. Though these transitory albums yielded mixed results, later albums like “Black Celebration” and “Music For the Masses” would see to it that the groundwork laid by earlier releases like “Construction Time Again” would be successfully built upon.