11 minute read

Karioi: connecting to whenua

Left to right: Bailey Hōhaia, Garry Almond, Kapohau Matiu-Wharepapa, Una Stephens, Willy Cameron, Tātana Moko, Renee Thomas, Karla Bradley, Tamu Mausii, Norman Petereit, Manaia Rāpata. Photo: Virginia Woolf

DIANNE BROWN, KAIHĀPAI (PROGRAMME MANAGER) WHENUA ORA

Karioi is our new project, focused on growing ancient crops using a tikanga-led approach. It found us out on the māra last November, getting our hands and knees dirty as we planted heritage varietals of kūmara and taewa (Māori potatoes). This māra is down the road from Te Āwhina marae in Motueka. Here, we planted a colourful range of complementary crops between the vegetables that will suppress weeds, help to improve soil conditions, and provide additional kai.

Karioi got off to a soggy start. The unseasonal deluge of rain we experienced in spring meant gumboots were essential for our first planting sessions. Then the Boxing Day 2020 hailstorm over Motueka really tested the resilience of our budding plants. But our good spirits have prevailed, as have, thankfully, most of our plants.

After months of planning, we were very excited to launch Karioi and have already set some ambitious goals for this project. We aim to:

• reconnect our whānau to our whenua • foster local resilience and food sovereignty in our community

• build evidence and knowledge on the impact of our tikanga-led practices on our soils, water and crops.

The plan is for three-quarters of the kai grown to be made available to participating whānau, provided to our marae for whānau events, and saved for seed. Chef Martin Bosley, via the Kono distribution business, Yellow Brick Road, will sell the remaining kai to restaurants. This will help us to test the market for opportunities for indigenous crops, grown using tikanga-led practices and with a unique brand story.

Karioi has been developed within the context of Whenua Ora, our land and water wellness programme which impacts on all of the activities of Wakatū.

This work sits within our kaitiakitanga framework, which is a commitment to a 20-year transition towards tikanga-led farming practices across our portfolio of businesses. It reflects our roles and responsibilities within te ao Māori, in relation to the long-term sustainable use and care of land and water use, including te taiao, a concept that acknowledges the interconnected relationship between all things.

Karioi is a tangible start to the long journey ahead of us. It is about so much more than gardening and crops. It is also the sharing of skills, knowledge and experience with whānau and specialist advisers from around Aotearoa.

Glen Skipper has inspired us with his kōrero and practical experience he’s gained at Te Moeone, a hapū-based māra in Taranaki. Nick Roskruge, a professor in ethnobotany at Massey University, shared his extensive knowledge on soils and cropping.

We have developed a programme of six wānanga that will be held across a 12-month period, to align with the planting and growing season. Two wānanga were held in 2020, and we’re looking forward to the upcoming wānanga and the rich kōrero that participants will share.

We currently have 15 whānau participating in our wānanga, which includes four who are already part of Kaupapa Tupuranga. This programme engages whānau within our business to be employed and gain transferable skills while connecting to whakapapa and whenua. Issue two of Koekoeā has more information about Kaupapa Tupuranga

Over the next 12 months we hope to expand our wānanga to 35 whānau, including 12 paid roles via Kaupapa Tupuranga. If you are interested in finding out more about this programme, please contact Hōani Tākao (hoani.takao@wakatu.org)

A TIKANGA-LED APPROACH

Our commitment to a tikanga-led approach to the māra has generated some interesting discussions during wānanga held so far. We are committed to integrating mātauranga Māori in the project’s design and operation. This includes implementing our kaitiakitanga framework by using our soil mauri/health scale, and incorporating maramataka, the traditional Māori lunar calendar.

But how do we strike a balance between tradition and customary knowledge and innovation? After all, ‘progress’ for our tūpuna has been the result of innovations large and small over the generations. Therefore, under a tikanga-led model, can we use a tractor to help with ground preparation and weed control, or should we only rely on manual labour and hand tools?

Certainly, the adoption of any technology comes at a price. While we know our people have always embraced innovation and have a dynamic approach to new technology, we need to ensure we are deliberately selecting only those advancements that support rather than undermine our customary practices and values. Wakatū is committed to this transition, but we still have considerable learning ahead of us as to how we apply these tikanga-led practices at scale and to a variety of crops, while maintaining the financial viability of our land-use choices. Karioi will help in making these strategic decisions.

Taewa being planted.

Photo: Virginia Woolf

What have we planted so far, and why?

• 0.5 hectare has been planted in 14 kūmara varietals, and 7 taewa varietals alongside black and white kānga (corn) and kamokamo.

• 1.6 hectares have been planted in a summer edible annual mix for cover crops - strawberry, clover, forage brassica, phacelia, sunflower, oats, vetch, sweetcorn, peas, daikon radish, green globe turnip, green beans, pumpkins, and small seeds such as chicory and plantain.

• Crops have been selected for their ability to improve soil health, while also producing food.

The forecast yields from our season one crops are:

- 300 kilograms taewa

- 400 kilograms kūmara

- 3000 pumpkins

- 100 kilograms kamokamo -

1000 kilograms kānga (corn)

We are planning to share what we have learnt, including highlights from our wānanga. We intend holding open days on the māra so that our whānau and our kaimahi can see, touch, feel, taste and learn from Karioi.

We’ll also continue to share news about Karioi through annual and special general meetings, e-pānui, the Wakatū website, Facebook, and Koekoeā. If you are Wakatū whānau and are interested in participating in future Karioi wānanga or attending an open day, please email info@wakatu.org with ‘Karioi’ in the subject line.

A CELEBRATION OF INDIGENOUS FOOD

Finding the appropriate name has been an important part of the kaupapa of our indigenous crops project. Following discussion at an early design hui, two possible names were put forward: puanga kai rau, a name associated with the stars and abundance, and karioi, an old word associated with hākari, or feasting. Having been given both options, kaumātua Rore Stafford selected karioi.

Rōpata Taylor shares more detail about the origin of the name.

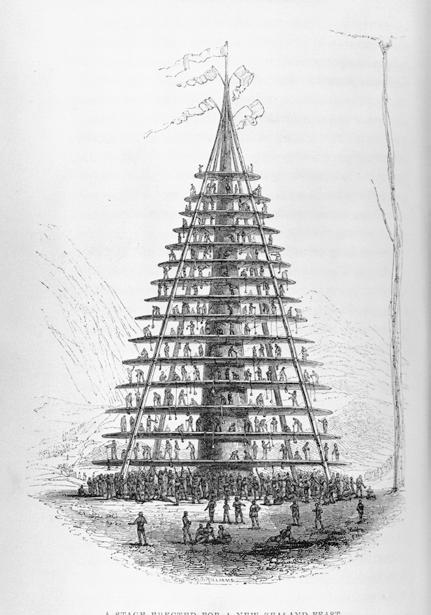

Karioi was first suggested by Manaaki board member Te Pūoho Kātene. He used the shape of a traditional karioi as a model to explain the key aspects of tikanga-led gardening, of connection, expression and wellness. Te Pūoho quoted kuia and past Wakatū board member Tuaiwa Rickard, who once said, ‘Somewhere in my past is my future.’ Te Pūoho first learnt about traditional karioi from our whanaunga, Matiu Rei.

Karioi is not a term that is often used, but its origins and meaning go back to the whakapapa of the people of the heke and is associated with hospitality, feasting, abundance and the showcasing of food.

In a modern context, you might see kai arranged on a raised platform at a hākari on a marae and forming a second layer of the food.

The kai on the platform is usually special or are delicacies associated with that area. That platform is called a karioi, and the name refers to the food trellis built by our tūpuna. Traditionally, celebrations like hākari were held outside and as part of the feast, people would climb up the trellis or pyramid-like structure to get the food.

There is another level of connection. Our whānau originated in Kāwhia and Whāingaroa, and Karioi is the maunga from that region. Finally, the kaupapa of the Karioi project is about protecting our food sovereignty and celebrating our traditional kai. And so the association with hākari and manaakitanga were some of the reasons why karioi has been revived as the title for this important project.

Samuel Williams, 1788–1853 : A stage erected for a New Zealand feast [1835].

Ref: PUBL-0101-139. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

MĀRA – A PATHWAY TO WELLBEING

Glen Skipper, a poutiaki taonga at New Plymouth District Council and one of the whānau specialist advisers involved with Karioi, shares his thoughts on the benefits of māra-based projects.

‘To me, Karioi is so much more than being about food. It’s about transformation. It’s about how to rebuild our communities, how to imbue the tikanga, principles and values of our tūpuna back into our everyday lives. It’s about giving life to intergenerational thinking. When I heard about Karioi, my first thought was, ‘How can I get involved in this project?’

I’m excited to be part of it. Working as a collective, an organisation like Wakatū can have such a positive impact on the thinking and evolution of this type of project, not just for Wakatū whānau, but for all Māori and other indigenous communities. From my experience, it’s important to see Karioi as a long-term project.

It’s going to take at least three years before we will be able to look back and say, ‘We know stuff that we didn’t know before’ and think more about what we are trying to achieve. For now it’s about building trust, working together, getting to know each other, and building a common language.

It will take time to get everyone to reach the level of understanding around the processes for these particular crops. Until you have done a season once, or twice, or three times, you can’t look back and reflect on what went wrong and what went right; you’re not able to have those deeper insights. Around 10 years ago, we started Te Moeone, a hapū-based māra in Taranaki. We came to māra, not because we were interested in gardening as such but because, through it, we could set up a framework of empowerment and re-indigenisation.

Working with the māra allowed us to identify pathways back to the aspects of Māoritanga we had identified, back to ora, to waiora, to all those different types of wellbeing. Māra intrinsically has six or seven types of indicators, just by doing it. It is an activity to promote, foster and advocate as an indigenisation tool.

People from the outside might look at us and think, ‘Oh, they are growing food’, but actually food isn’t the primary reason for why we started a māra – in fact, food is the happy coincidence that comes at the end if we do it right. The māra becomes a conduit around so many other things.

We began by inviting whānau to wānanga, and off we’d go, out into the māra. Our kaumātua could be there, our tamariki could be with us, we could eat together, everybody would be happy, it was positive. We weren’t really concentrating on food, we were concentrating on mahi tahi, working together. We’d have wānanga about maramataka and te reo Māori, including learning karakia.

Glen Skipper

Photo: Kate MacPherson

We did māra reo, so it became a place where we practised using reo. We also had kōrero about our tūpuna and their actions, around Parihaka, around their history of māra, how they put their hands to the plow.

Māra projects are a practical way to learn about the impacts of intergenerational thinking: the choices that we make this year, what we do to the soil, what we plant, what is our seed selection – it all has impacts on the years to come.

If we prepare the māra, if we put all of the good stuff in there and we make it the best place, then the potential of the seeds, the plants and fruits, and the value of them will come to fruition.

I believe that if we teach someone about seed selection and seed saving, and that it is for the values and potential of their māra, then we start to show them what is their own potential and the impact of their own actions, in a wider context. If we can keep someone in the māra for three to five years, it changes them, it changes the way they think because they can see the positive and negative effects of acting intergenerationally.

People who are māra people have to think about what they are doing, now. You can’t put a seed in the ground and eat it tomorrow; it’s something that is in the distance. You have no choice but to think of the future and the consequences of what you are doing, about what you did last year, and what you did the year before.

It’s been a great experience being involved with our Wakatū whānau, and a real privilege to be part of Karioi right from the start. Everyone has been welcoming, and they’ve had a lot of questions. There has been an awesome amount of trust, and people are upfront about where their strengths lie. None of us has all the answers, but there are people with expertise and experience in different areas, so collectively we should come up with something amazing. It’s an exciting project. It’s leading the way.

It also reinforces for me the need to value our connection with whenua, our connection with kai. It is our first rongōa, something we partake in at least two or three times a day. The māra is a pathway back to those connections that we need, to bring us to a place of wellbeing.

Kānga seeds

Photo: Claudia Meister

Turi and Micah McFarlane.

Photo: Claudia Meister