12 minute read

Mauī John Mitchell: a lifelong passion for whakapapa

Mauī John Mitchell

a life-long passion for whakapapa

Mauī John Mitchell (Ngāti Tama, Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Toa, Taranaki Tūturu) and his wife, Hilary, spent over ten years researching and writing the four-volume series Te Tau Ihu O Te Waka, a history of Māori of Nelson and Marlborough.

The series covers the history of Māori in Te Tau Ihu, the impacts of colonisation and European settlement on Māori, and land issues arising from colonisation. Included in the books are lists of baptisms, marriages, census and land ownership records. The books are taonga for current and future generations.

A former Wakatū board member, John shares with us some stories from his whānau and childhood, and influences that led to a life-long fascination with whakapapa and history.

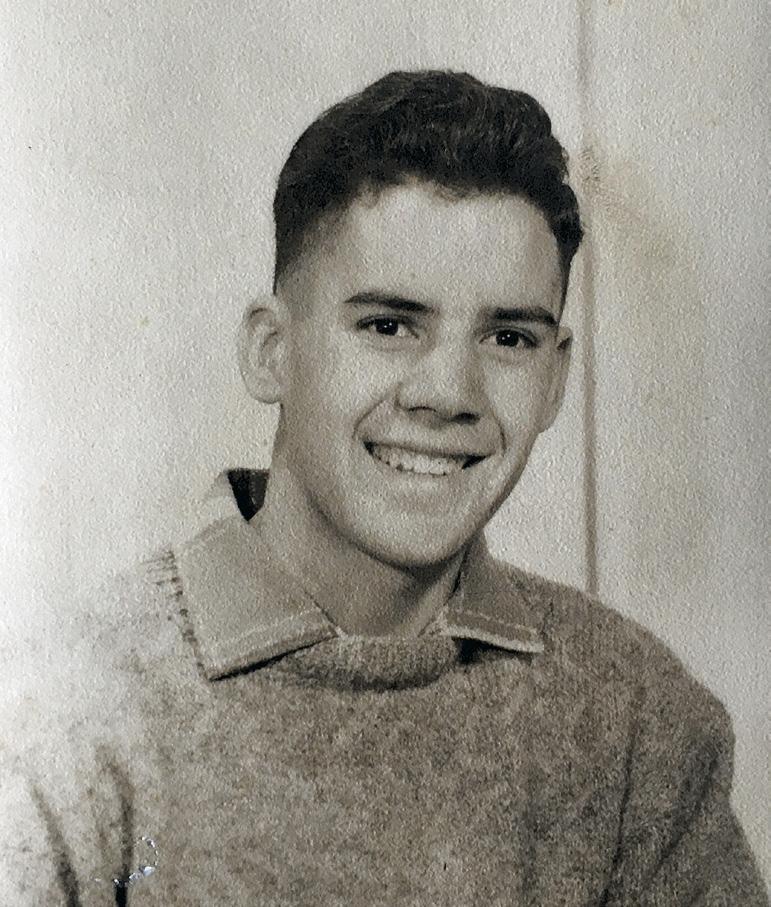

A young John Mitchell in 1959.

Iwas born in Tākaka in 1941. Mum was pregnant with me when Dad volunteered and went overseas with the army, serving in the Middle East. Grandad Jack Small (Pop) had also volunteered, serving in the Pacific in the airforce. Since Mum and Nanny Small were both without husbands, it made sense for Mum and her newborn (me) to shift to Nelson to live with Nanny.

World War II was Pop’s second world war – he had volunteered as a teenager, serving in the trenches in

France during World War I, where he was seriously wounded. The family joke is that Pop twice lied about his age, adding years to serve in World War I, and subtracting years to serve in World War II. Pop returned home first, but Mum and I stayed on in Nelson until Dad, badly wounded, was repatriated some months later, by which time I was over four years old. We then went back to Tākaka, spending a lot of time with my cousins at my Aunty Dool’s farm at Motupipi. The farm was still being broken in, so a few of us boys did the hard work with the hand augers drilling the holes to take the gelignite. We’d pick up the debris after each explosion and fill in the craters where the stumps had been. Exciting stuff for young boys! My cousin Bob and I certainly learnt the tricks of that trade, to our eventual regret: we stole a couple of sticks of gelly, fuse wire and detonators, and decided to give the local community a rev-up by setting them off in the fork of an old tree in Bracket Bickley’s walnut orchard, beside the Motupipi Hall and School. We just intended for a loud bang to wake everyone up. We got the loud bang all right, but hadn’t counted on the tree being demolished.

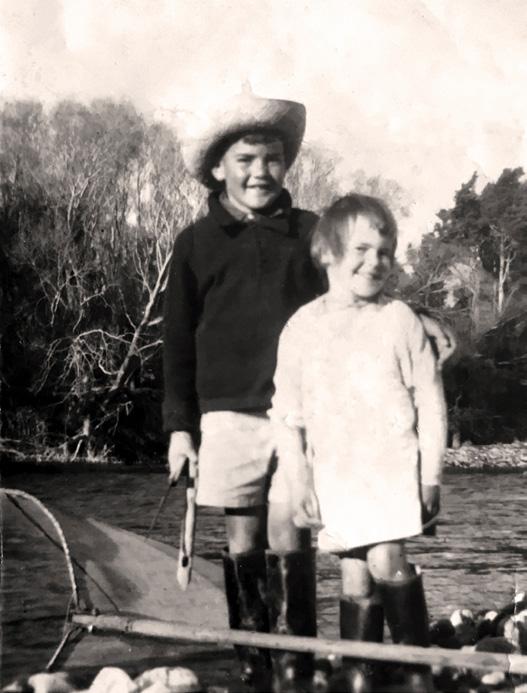

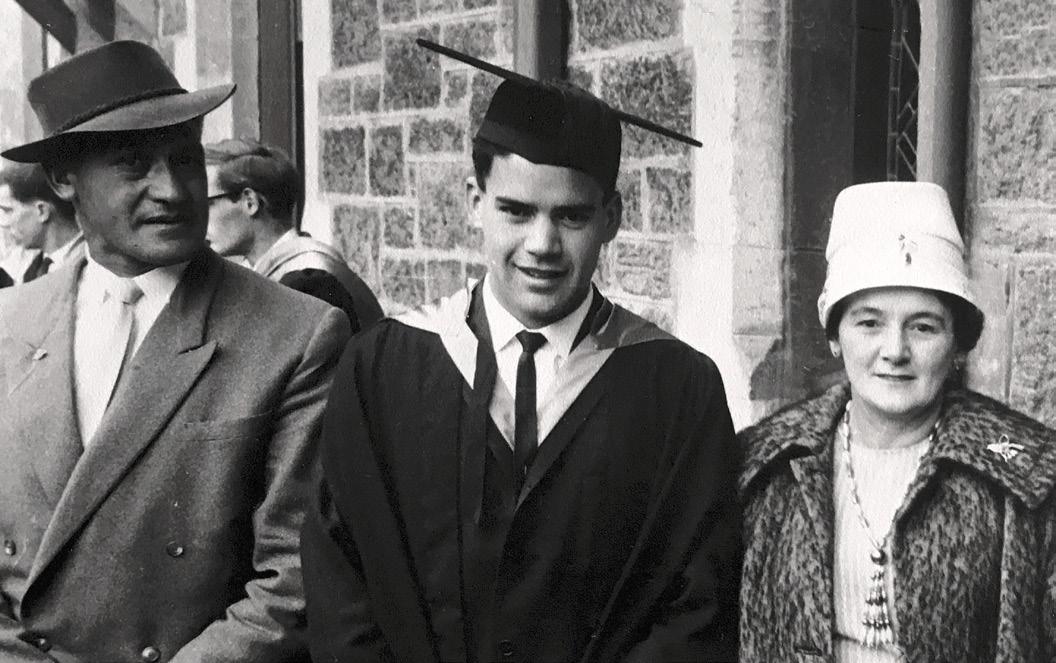

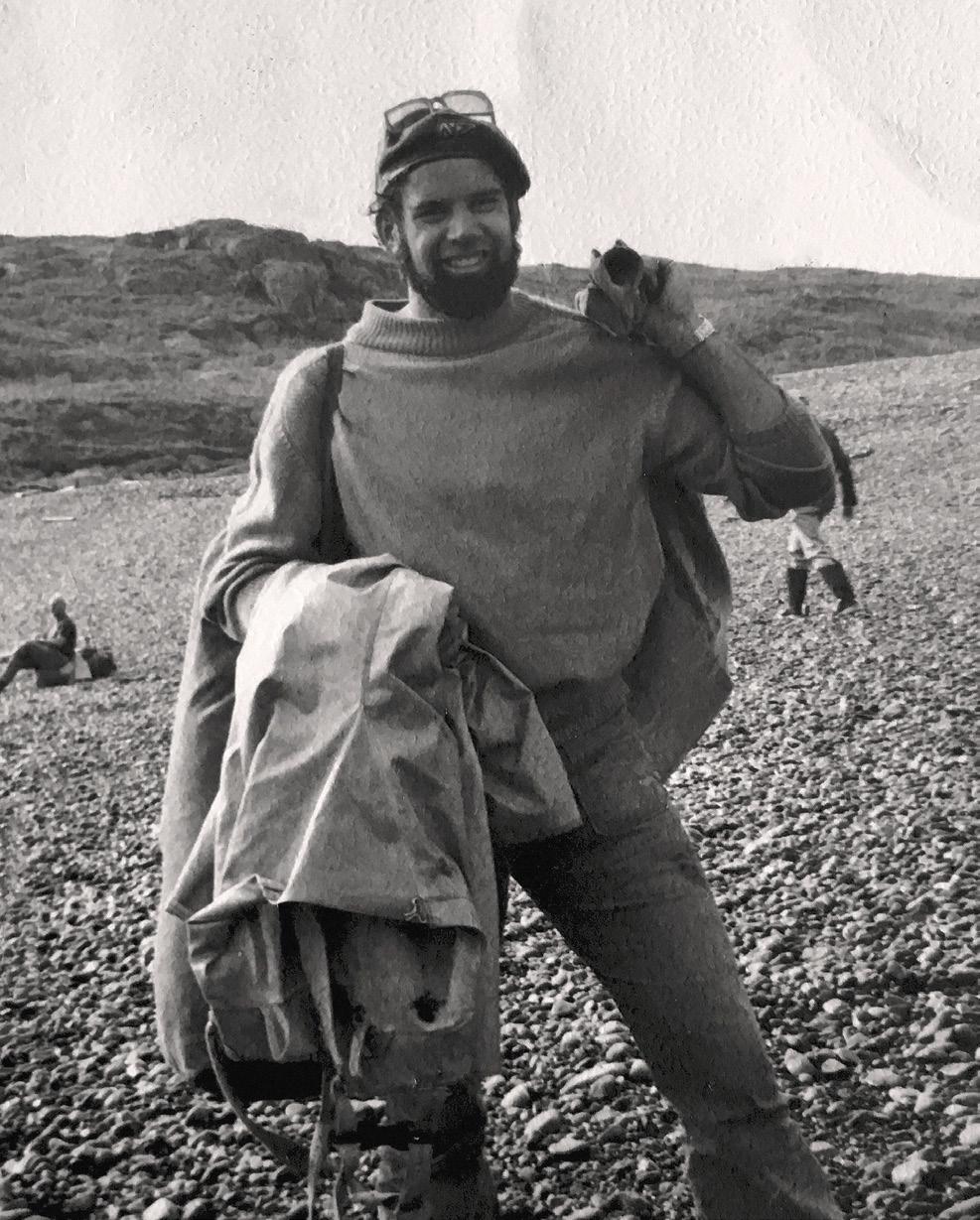

Clockwise from top left: John with his mother Doreen (Do) Mitchell in Nelson, 1942; John with his sister Dianne in Mōhua, 1951; John at the stern of an Outward Bound cutter, Anikiwa, 1976; John with his parents Mo and Do Mitchell at his graduation in 1962.

We got a thrashing from Uncle Ted and Dad, had to visit and apologise to Mr Bickley, and agree to six months of chores on his farm to make up for his loss. We also had to apologise in person, and in writing, to Miss Grooby, principal of Motupipi School, who was thoroughly traumatised, and had to face a real dressing-down by Senior Sergeant Strawbridge, the local police officer. Aunty Dool was the only adult who felt sorry for us, sneaking us dessert when Dad and Ted had denied us that as a further punishment.

Other relatives, including the Mason and WardHolmes families, lived in Tākaka and throughout Mōhua, and we spent many happy weekends fishing and partying with them at Tōtaranui, Tata, Pōhara, Patons Rock, Puramakau, Tukurua, Kaihoka, Paturau, Rakopi, Anatori and parts in between. Drag-netting with 50 or more whanaunga on the ropes is a lot of fun. So were the campfires at nights – a keg for the men, ukes, guitars, tea-chest basses, songs, borax, laughter. We had a wonderful childhood. Dad was a very keen hunter and fisher, and knew the mahinga kai of Mōhua better than most; he had hundreds of fishing marks around the bay, and I wish I remembered them. We used to joke that if the old man put out a whitebait net on the back lawn, he’d catch more than anyone at the river. Mum and Dad had a lot of friends in the district. I think Dad was well respected because of his war service; not only was he wounded but also he was a prisoner of war who had managed to escape. Dad and George Woolf combined their postwar rehab loans to create a contracting business, Mitchell and Woolf, for freight cartage and agricultural contracting, taking on ploughing, haymaking, lime-sowing, and the like. They carted the huge penstock pipes and reinforcing steel from Waitapu Wharf in Tākaka to the Cobb Hydro

scheme, one load every two weeks. During school holidays I used to stay with Dad in his hut at the Cobb – sometimes there were 8–10 boys like me up there with their fathers. We’d cadge rides around the construction sites in the big trucks, on the bulldozers and in the draglines – no workplace health and safety in those days. On fine nights, Dad and others would spotlight for deer or catch tuna in the river and lakes. And on lousy nights, the men would teach us billiards and snooker in the YMCA Rec Hall, or let us ‘help’ at the illegal Crown & Anchor, Coon-Can and Blackjack gambling schools that were running in the back rooms. What an education for young boys. I went to primary school in Tākaka, but Pop wanted his eldest grandson to go to his own alma mater, Nelson College. So, in 1954, I went back to Nelson to live with Nanny and Pop and attend Nelson College. I had to help eke out the cost of my keep by gardening, lawn-mowing, and working some evenings and weekends in the Smalls Taxi office. Unfortunately, by then Pop’s terminal cancer had advanced and he died a few months after I arrived, and Nanny similarly succumbed a few years later. I stayed on with my uncle Bill Small and his wife Veronica. By my fifth form year, Mum and Dad were finding it difficult to continue funding me at college – by then there were four more children at home. I was offered an apprentice cabinetmaker position in Tākaka, but the headmaster wouldn’t sign off the papers for the Apprenticeship Board. He said. ‘You’re coming back to college, boy. You will pass School Cert this year, then UE next year and Higher School Certificate the year after, and then you’re going to university. In the meantime, you will apply for these grants, which will cover your parents’ costs while you’re here.’ He produced application forms for Māori scholarships and grants and told Dad he would have to provide whakapapa details. This was probably the start of my journey through the intricacies of whakapapa and iwi, hapū and whānau history. Dad didn’t do whakapapa, but his oldest sister, the fearsome Aunt Sylvia Rangiauahi Thomas (née Mitchell) was our whānau kaiwhakapapa. Every evening for a fortnight, we ground our way through the generations of tūpuna so I learnt the bloodlines (and the heke/taua) connecting our Mōhua whānau back to Taranaki. To this day I can still produce those whakapapa from memory, and I always have images of her while doing it.

I went to Canterbury University in 1959 and it was there in my first week that I met a gorgeous girl, Hilary Fahey, from Kūmara, West Coast. I graduated with BSc in Geology, Chemistry, Physics, Maths, before switching to Psychology, Sociology for MSc (Hons) and a PhD. Hilary and I married in 1966, and I secured a lecturing position in Canterbury’s Psychology department. During the next seven years, I was the only person of Māori descent on the teaching staff at Canterbury; another Māori was a technician in one of the engineering departments. I combined lecturing with, alongside Hilary, running the first co-ed hostel at Canterbury. We were part-funded by Ministry of Foreign Affairs to house up to 100 sponsored overseas students. They were a wonderful diverse group of Asian, Pasifica and African students.

John, warden of Outward Bound in Anakiwa , from 1974–1978.

We became involved in a range of protests including ‘No Māori, No Tour’, the Vietnam war, spy stations at Weedons, and in a huge battle, which escalated within the university, aided by students affiliated to Ngā Tāma Toa, over the introduction of Māori Studies to the curriculum at Canterbury. By the early 1970s, I had authored or coauthored 12 peer-reviewed scientific papers in academic journals, had made presentations at two international research conferences (Holland and USA), and at that time I was one of the youngest senior lecturers at Canterbury. I was doing well in the university system, but getting tired of it. Then, for five glorious years, from 1974 to 1978, I had the best job in Aotearoa: I was appointed Warden (now called School Director) of the Cobham Outward Bound School at Anakiwa in Queen Charlotte Sound. I still think Outward Bound has the most clearly formulated philosophies and bestdeveloped programmes for the social, physical and moral development of late adolescents and young adults. And what a stunning environment for our own children to grow up in. We were so lucky.

Back to Nelson in 1979 where we became commercial tomato growers for three years. I was also Whakatū Marae secretary. In that time we relocated buildings from Nelson Hospital for the marae and for the adjoining Kōhanga Reo, and built the Kaumātua Flats, with the assistance of people on the Māori Access (MACCESS) and public employment programmes (PEP) schemes. Other teams were carving poupou and creating weavings. The construction of the whare tūpuna, Kākati, was the last project I was involved in for the marae. At about the same time, opportunities came along for Hilary and me to compile social impact reports on major engineering development proposals. Most contracts also required us to research the Māori history of the development areas. We conducted hui and interviews, many of which threw up historic grievances and Treaty issues. In 1985, we formally established Mitchell Research as our full-time occupation. From this background we have come full circle back to local, regional and national Māori issues. I was honoured to serve two terms on the Board of Wakatū Incorporation, from 1988 to 1994, and over much of the same period I was elected inaugural chair of the Ngāti Tama Trust and also deputy chair of Te Rūnanganui o Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka a Mauī. I was also appointed to the Māori Fisheries Commission (later the Treaty of Waitangi Fisheries Commission/Te Ohu Kaimoana) for 11 years, and the Crown Forestry Rental Trust (six years) – all wonderful experiences in the company of some of this country’s the most impressive rangatira Māori. During those early years, when the Rūnanganui represented all eight iwi of Te Tau Ihu, up to 70 kaumātua would attend meetings. Much of our initial work was directed towards Waitangi Tribunal claims, although marine farming activities (both applications and objections) also occupied much of our time, sometimes with positive outcomes. Arguments with the Marlborough District Council over water-space allocations, and the ensuing Foreshore and Seabed issue, certainly drained our resources. The Rūnanganui also threw its weight behind the organisations that were pressuring the Anglican Church to return the Whakarewa lands in Motueka to Māori ownership. The Waitangi Tribunal had signalled that it was not interested in receiving eight or more versions of local Māori history, and insisted that a single generic history embracing all iwi be presented, as a backdrop against which the separate iwi and hapū could submit their particularised statements of claim. Hilary and I were appointed by the Rūnanganui to prepare that history, which, after the hearings, was modified to become the backbone of Volume I of Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka. As the hearings proceeded, we contributed research reports for several iwi and Wakatū Incorporation on various aspects of our complex local history. Into the 2000s, we undertook more research

JOHN MITCHELL

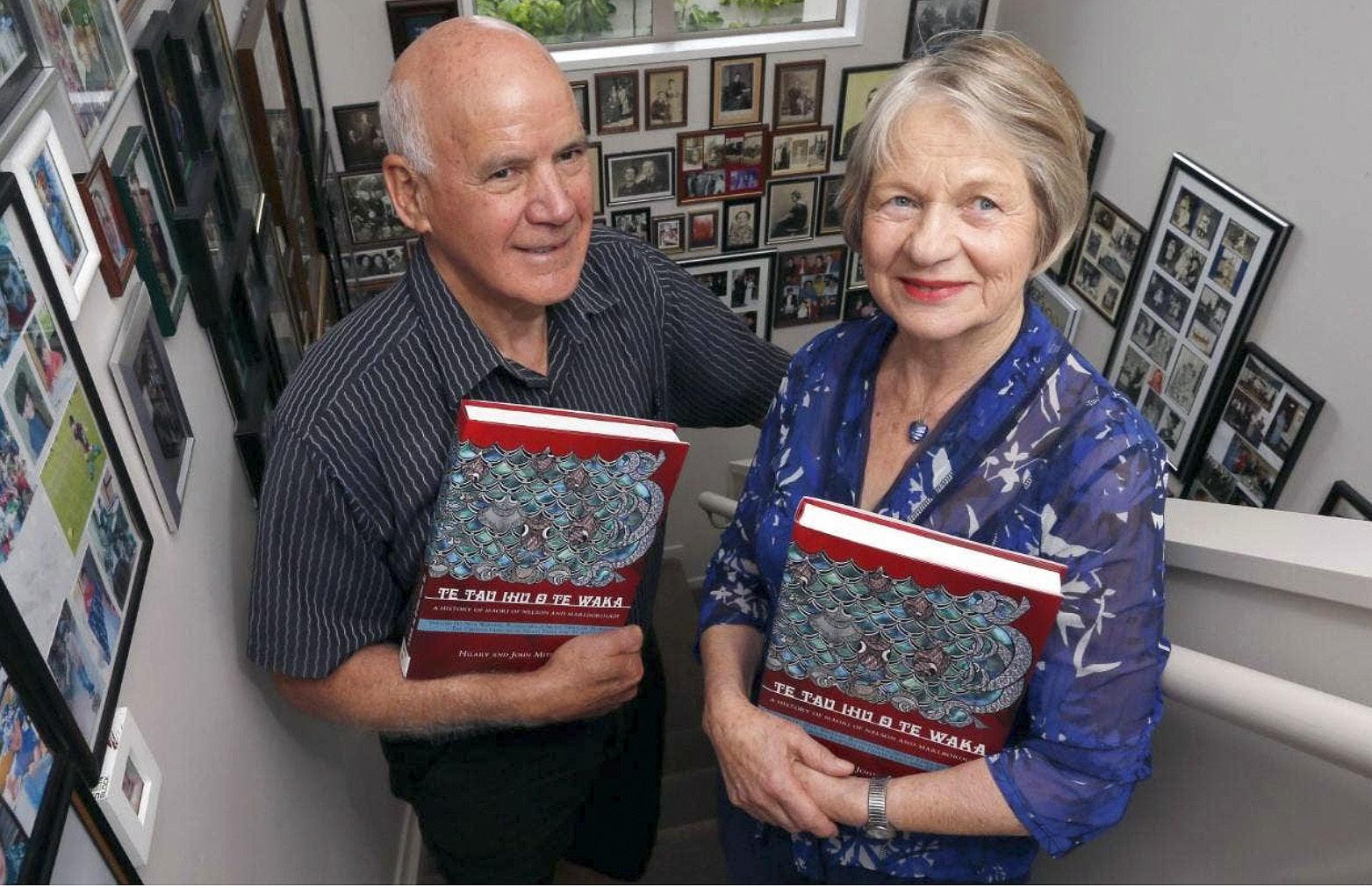

John and his wife, Hilary, in 2015, holding copies of the final book in their Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka series. Photo: Stuff Limited

and the compilation of three more volumes in the Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka series. Currently we are in the final throes of producing a biography of Isaac Coates, an artist from County Durham, England, who lived in Nelson between 1842 and 1845. During that time he painted watercolours of 58 Māori of Te Tau Ihu and the Cook Strait area, including several who were founding tūpuna of the iwi of Wakatū. We have lived in interesting times. I wish to acknowledge Hilary: wife, mother of our three fine children, registered partner of Mitchell Research, and partner in every other way. Hilary has one of the finest minds I know, and she lives by a moral code that I can only but admire. Her memory for Māori whakapapa and events in our history is better than mine, and she pays attention to details which I might otherwise miss. Without Hilary, I very much doubt that I would have enjoyed the rich life with which I have been blessed. I may have taught at Canterbury University as I was proceeding down that avenue when we married, but without Hilary’s encouragement, guidance and steadying hand, I certainly would not have run the co-ed hostel there, nor the Outward Bound School, nor set up Mitchell Research. And I probably wouldn’t have returned to live in Nelson and become involved in local, regional and national Māori issues. I have been incredibly lucky.

Kati. In large part I have been shaped throughout my life by an enormous number of kind, generous and supportive people, Māori and non-Māori, the majority of whom have since joined the ancestors. To them I express my eternal gratitude and offer a poroporoāki:

E ngā mate o tōku takiwā, o tōku marae, o ia marae o ia marae, haere koutou, haere, haere. E whakawhetai ana ahau ki a koutou mō ā koutou mahi manaaki mōku. Haere koutou ki te tini, haere ki te mano, haere ki ngā tūpuna ki runga i tā rātou ara tapu i waenganui i ngā whetū.

Haere koutou, haere, haere, haere

Tīhei Mauri Ora!