17 minute read

A dream fulfilled

WORDS AND PHOTOS BRIAN STEWART

Dad initially owned a Ford Pilot V8, followed by a succession of Zephyrs (MKI through III) and, after being treated poorly in a Chrysler dealership, two MKIVs, then a Falcon, a Cortina, and finally a Ford Laser. Consequently, when I became a keen follower of motorsport I showed a strong bias towards Ford. With the announcement of the GT40 back in ’63 I avidly followed the exploits of the car and its drivers in the motor magazines of the day. Here was a car to lust after.

At age 13, the Le Mans victory in ‘66, especially with a couple of Kiwis at the wheel, was, in my young eyes, the pinnacle of motorsport achievement. I guess the dream started back then. A particular photograph, a rear view of a couple of MKIIs dicing with a gaggle of other cars, including a pair of P4s and a couple of MKIs, through the esses in ‘66, stuck in my mind for many years. The GT40 remained a firm favourite throughout its racing career, and, although I also had a very soft spot for the F3L (P68) when it was introduced, the yearning for a GT40 was still strong for some years after they ceased winning races. However, being on the other side of the world to major sportscar action, I was resigned to the likelihood of never seeing my dream car in the flesh, let alone owning one. Desire gradually faded and the GT40 slipped well down in my consciousness for a couple of decades.

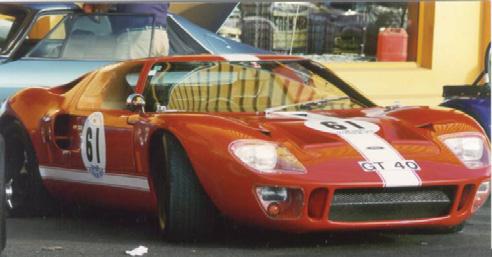

All that changed in 1990. Unbeknown to me an original GT40 was residing in New Zealand. I was at a classic race meeting in Dunedin and, there it was, a GT40 – in the flesh! All the memories came flooding back and I took as many photographs of it as I could. The car was chassis number 1078, and had been brought to New Zealand by AC/DC’s Kiwi drummer, Phil Rudd. It was doing a farewell tour of the country’s classic race meets before heading back to the UK with new owner Ted Rollason. Unfortunately the car hit a kerb and bent a wheel in its first race and was side-lined for the rest of the meet. However the flame was alive again, and was fanned by a copy of Ronnie Spain’s seminal GT40 book found in a Timaru bookshop at half price.

A couple of years later I came across another GT40 – this time in Gulf livery. Upon asking some questions I discovered it was a kit-car. I was flabbergasted. At the time I had no idea one could build one’s own GT40. Some years further down the line I spotted a GTD in Essex Wire livery for sale in Christchurch. I took a trip up to look at it and found that although it was a beautifully put together car, at six foot four inches I simply could not fit into it. I was gutted. My partner Carmen and I had been together about a year and she was with me at the time. Rather foolishly she said, “If you like them so much, why don’t you build one?” Wow! Talk about being given a green light… It is a comment she has regretted to this day.

Deciding that I would indeed build a GT40 the search began in earnest. A 1969 Ford 351 Windsor V8 engine cropped up not too far from me and, based on my reasoning that, if a 351 was good enough for the GT40 based Mirages and AMGT-2, it should be good enough for me, I bought it and stowed it in the garage. Next step was to closely examine the available kits. I discounted GTD as I had already established that it would not give me enough interior room. Closer to home was DRB in Queensland and Roaring Forties (RF) just out of Melbourne, and GT40 NZ. In 2000 Carmen and I managed a side trip to RF while we were visiting Tasmania, and I came away very impressed. So much so that I was on the verge of sending away a deposit when I spotted an article in New Zealand Classic Car magazine. The article covered all the current makers of kit cars and bespoke replica cars currently operating in

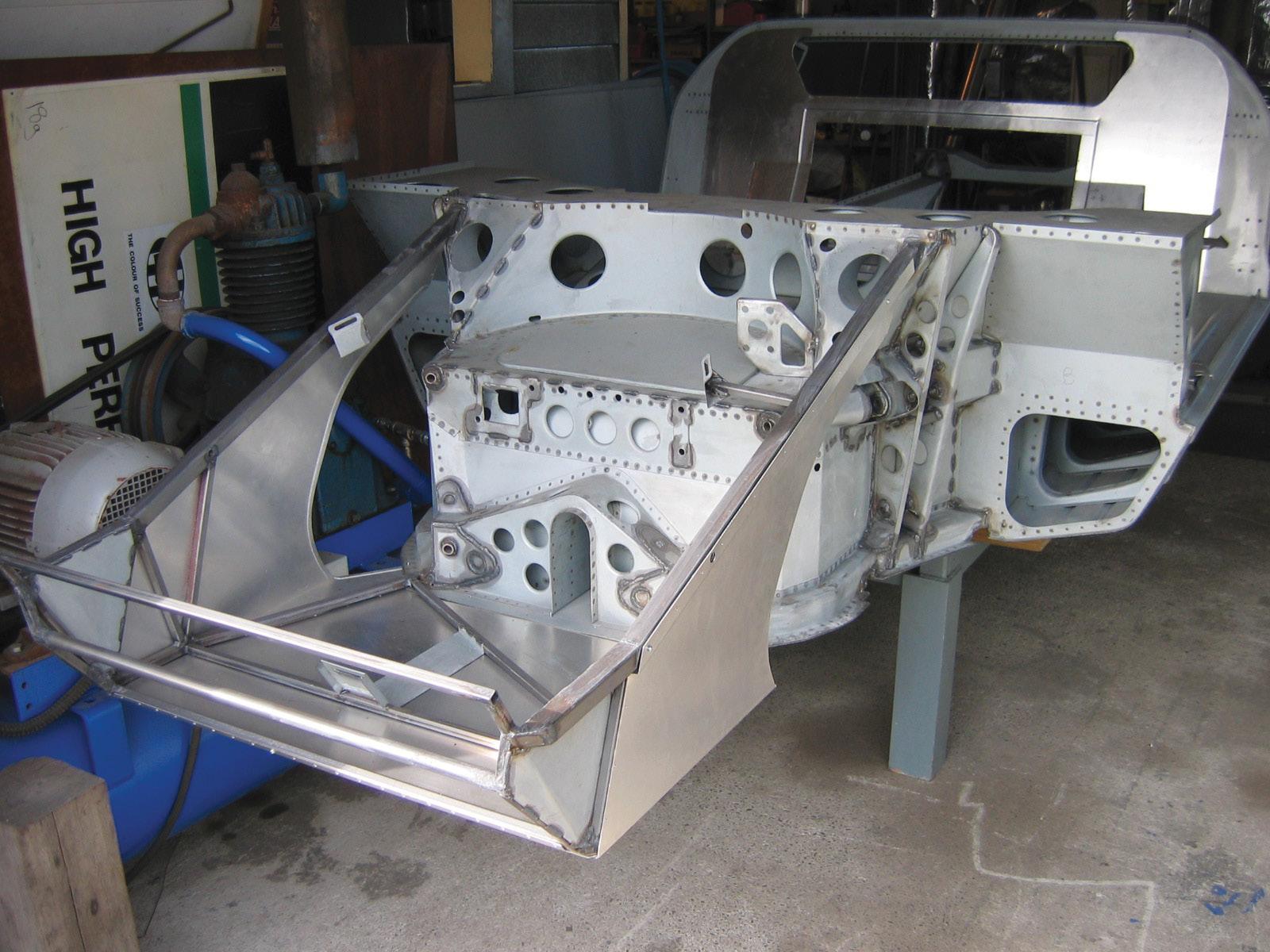

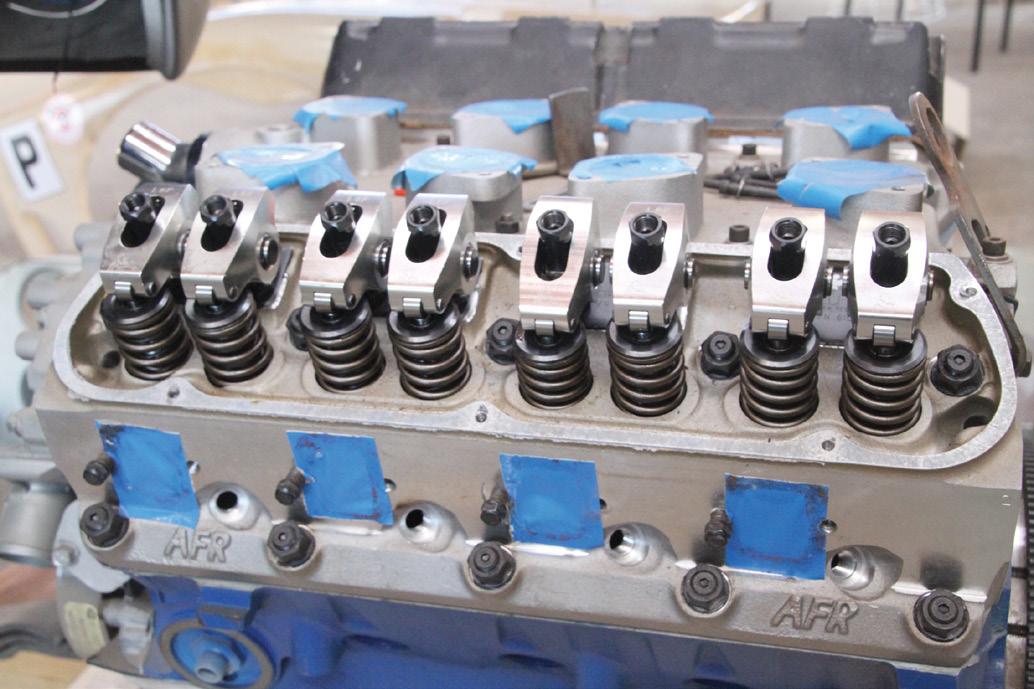

s My mono early on. s Engine assembly. Scorpion roller rockers and AFR 185 heads.

s Wheels after. s Anti-rust undercoat.

New Zealand. Among the photos was one of a GT40 built by Classic Car Developments (CCD) in Invercargill.

Invercargill was just two and a half hours south of me, so I rang the number and arranged a time to visit with Dave Brown at CCD. He didn’t have a car on-site, but was part way though putting together his second monocoque, destined, funnily enough, for RF.

Being built from original Ford drawings, it looked just the business and, after much discussion, Dave convinced me that going mono and as original as possible was a much better option than going spaceframe. We talked money and I calculated I could get a fair way through a decent mono for similar money to what I would have given RF. I agonised over the decision for some considerable time, but finally, in June 2001, I sent my deposit off to Dave.

Bad timing. Within a couple of months the firm I had moved to in late 2000 looked like it would go under and I jumped ship before the inevitable collapse. Such is life. There followed a period of 12 months of uncertainty as I contemplated my circumstances and sought new employment. However, as Dave had already started on my mono, we came to an agreement whereby I would drip feed CCD money as and when I could afford it, and progress would continue on my car.

In the interim I read all the books I could find, scoured the internet, and talked to any GT40 enthusiast who was willing to share tidbits of information. As a result I was able to identify and source many parts that would assist Dave in progressing my build. In this respect I was very lucky to be living in New Zealand at a time before bureaucracy forced many car wreckers to clean up their yards. Thus, I was able to relatively easily source such items as dash eyeball vents, demister grille, dash switches and warning lights, door hardware, interior mirror, wiper motor, wiper, washer bottle, handbrake lever, and a host of other original fitment goodies that would either bolt straight in or could be suitably modified. When I say relatively easily, that still involved travelling the length and breadth of the country visiting various wreckers, knocking on doors

s MKII rear clip.

of farms that had promising wrecks lying in paddocks or under trees, and visiting as many swap meets as I could.

I gained meaningful employment once again, but kept drip feeding money to CCD as the arrangement seemed to suit both Dave and me well. Over the ensuing 15 years progress was very slow and, at times, very frustrating, with parts purchased overseas often taking many months to turn up. Any spare funds I accumulated went towards stripping down and rebuilding the 351 under the watchful eye of a local engine specialist, and sourcing a manifold and a set of 48 IDA Webers. eBay became my friend, with searches created for ZF transaxles, CAV ammeters, Stewart Warner 240A fuel pumps, and aero engine oil coolers, among other things. The greatest success was scoring a 1971 ZF DS25-1 transaxle out of a very early Californian Pantera for what would be considered a very good price in today’s market.

Based on the 1966 picture burned into my memory I had decided I liked the look of the MKII rear, and that dictated bodywork and what wheels I should get. Magnesium was discounted as being too expensive and more difficult to maintain so, after much searching and numerous blind alleys I chose Halibrand wine glass style three piece wheels from Image Wheels in the UK, and Avon CR6ZZ tyres to fit.

The wheels looked great but I was not keen on the sharp delineation from the rim to the centre. I dabble a little in oils on the side and was able to exchange a painting for a set of laser cut inserts that were bonded into the wheels to give a more original look.

Around this time Carmen and I decided a holiday was in order so we combined a trip to Europe with a visit to the Le Mans Classic in 2006. There we got to meet many of the wonderful folk in the GT40 Enthusiasts Club and, through their generosity, we were both lucky enough to be offered our very first rides in a GT40. The high speed trip down the Mulsanne Straight is an experience one does not forget.

s Top coat. s Body trial fitted.

s Loom in.

Once back in New Zealand I was informed by those in the know that Bill Hough in Massachusetts had worked on the original cars back in the day and was the man to ask about bodywork. I contacted Bill and he was very good to work with. He was willing to make a MKI front clip with single nostril, doors and sills, and a MKII rear as I requested, but pointed out that the MKII rear clip moulds he had were very old and would need some work to get them into shape. A deal was done and work commenced. I’m not sure how old Bill’s moulds were, but when the bodywork finally arrived dimples made by the rivets holding the periscopes in place on the rear deck were plainly visible and a little bird later told me that the rear clip was cast off an original MKII race car. No idea which car, but a nice link with the past if true.

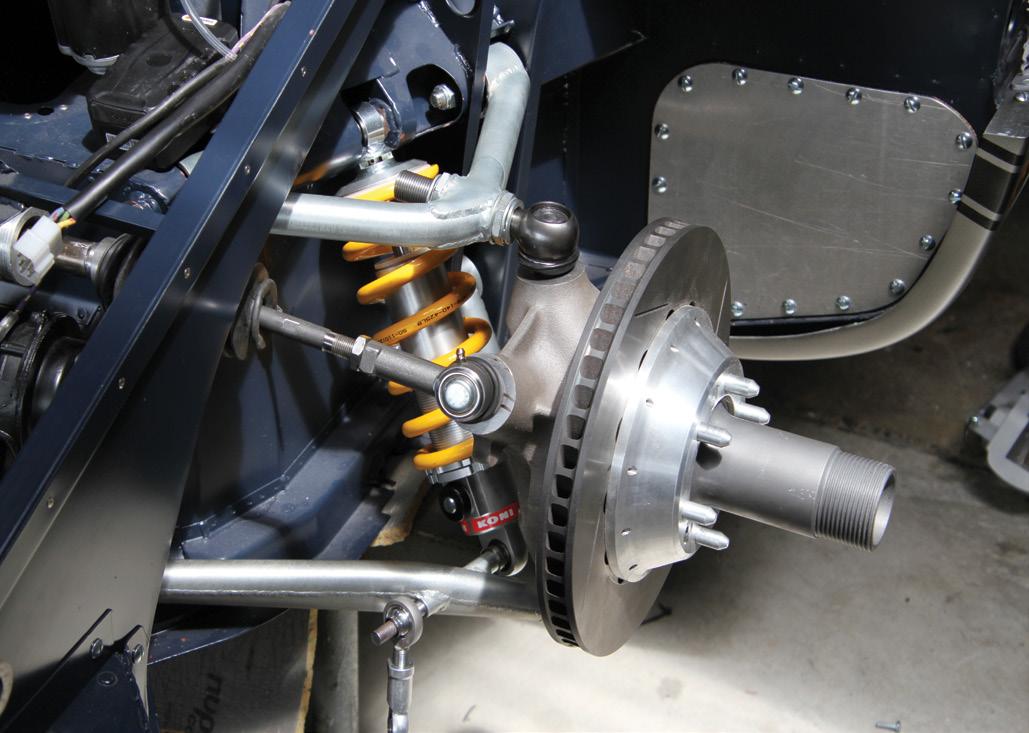

Brake calipers (Girling 18/4 and 16/4) and discs (AP racing vented) were ordered from BG Developments in the UK and Raceparts respectively and arrived very quickly. The engine was eventually finished, and the transaxle finally turned up (after languishing in a Los Angeles warehouse for two years), so both were promptly delivered to CCD, along with the body that I had prepped as far as I could. Dave and the lads had made significant progress, with the mono being almost complete, many of the suspension components made, and a myriad other little things organised.

With the roof made and fitted, and most body parts trial fitted, the engine and transaxle were also trial fitted, along with available suspension components. It was starting to look like a car, but at this stage we decided the mono was ready for paint, so everything was removed again.

I reiterate that all the above took place quite slowly over the space of some 15 years. In the interim CCD had built two other GT40s, was working on a third, and had supplied one other car and numerous monocoques in various stages of completion, all to overseas clients, and I felt that my project was being left behind somewhat. However, by October 2017 I was ready to cut back on my work hours and commit more time and money to getting the car completed. As a result, I came to an arrangement with Dave that John Shand (who had played a huge part in getting many of the CCD GT40s together, but was no longer with the firm) and I would spend a couple of days per week in the workshop. John was otherwise committed until early 2018 so I pottered away on things I was able to handle by myself, with some guidance from Dave, and from John when available.

Once John was fully on board things started to really progress. By this stage the body was all painted and we could begin final assembly. As anyone who has restored or built any car will know, “final assembly” is a very loose term, with most components being put on, taken off, then put back on and taken off again at least twice, and sometimes three or four times.

The first major job was re-installing the engine and fitting the eight inch twin plate clutch and transaxle. Then, with the alloy fuel tanks installed, we could plumb up the fuel system and check for correct function and leaks. The SW pumps made the correct noises, but one leaked, so needed stripping down and new gaskets fitted.

Next it was on to the electrics. An original style loom from Andy Booth at GT40 Gold Parts (along with numerous other bits and pieces) was laid in and connected up with an Autolite regulator, a refurbished Autolite alternator from a 1969 Falcon GT, and an original distributor retro-fitted with a Petronix electronic ignition module. Power was supplied by a sealed 12V gel battery installed at the front of the passenger footwell.

Still a long way to go, but with fuel, electrics, and a cooling system in place, what else would you do but try to start it? After a few slow turns it coughed into life, but only on 6 cylinders. A bit of

s Body colour on. The car in the background is a very original recreation of a car driven by Denny Hulme, being built for a UK client.

s Gauges and switches fitted. s Rear hubs, before and after.

s Front suspension.

a play with the HT leads got it on 7, then some tweaking of one of the carbs had it running on all 8. Not bad for lying idle for over ten years. It was tempting to start it every time I revisited the workshop, but sanity prevailed and we got on with other, more pressing tasks.

The pedal box was fitted as far forward as it could possibly go to accommodate my lanky frame. Everything between the front bulkhead and the pedal box was a tight fit, so it was with a huge sigh of relief we were able to get all the plumbing and, more importantly, me, fitting. I wanted to use the original style handbrake lever and actuating mechanism, and with the pedals so far forward it required some extra fiddling with routing the cable and the making of a custom pulley to get it to all in place and working well. Front and rear suspension was completed and fitted up with Koni 8212 coil-overs, then the steering rack with MGB internals was fitted.

Front and rear hubs were machined, as were disc bells. Once that lot was assembled the car was put on its own feet. Probably about time as the tyres on the wheels of the build stand had perished and collapsed as soon as we tried to move the rig.

The interior was then fitted, having been made to original specifications and with reference to original photographs, by a very clever local upholsterer in Dunedin. With the seats in, the 4-point harnesses could be installed and windscreen and mirrors fitted and adjusted.

The final task was manufacturing the rear axles. These started life as Rover P6 units that were cut in half and a custom axle welded in and machined to accept VZ Holden Commodore SS inner CV joints. OK, they’re not Rotoflex couplings, but MKIIs had CVs and I’m happy with the look of the end result.

With the axles fitted the next step was to go for a drive so on Friday, 1 March 2019, a little over 18½ years after I embarked on this crazy journey, the car moved under its own power. Woohoo! Noisy little sucker it is too. The next week we fitted the extinguisher system and then took it to the local race circuit for a bit of a shakedown.

I’d like to say it performed faultlessly, but it didn’t. We had incorrectly put a ballast resistor in the circuit for the Petronix ignitor (I was originally going to run a twin point distributor) and hadn’t thought to remove the ballast. This ultimately caused a severe misfire that was easily rectified by simply bypassing the ballast. Another electrical gremlin made the gauges inexplicably all suddenly stop reading momentarily from time to time and the speedo would not work. Other than that, it handled very well, pulled like a train, and elicited much favourable comment from other folk at the track.

The following week I trailered it home and left it in the hands of Roy Macdonald to get it certified, warranted and registered, having been already approved by the Limited Volume Vehicle Technical Association (LVVTA).

So – dream fulfilled. Despite looking a little like XGT-2 the car is not a recreation of any particular GT40, but rather is an incarnation of my ideal GT40. It is mostly MKI, but with a MKII tail and rear subframe, and MKII style CV joints instead of rubber doughnuts. One major concession to modernity I have made is the installation of an electric water pump (a) to keep it cool in stop/start city driving, and (b) to increase interior room by doing away with the usual bulkhead bulge. Overall, I am very pleased with the result.

Would I do it again? Probably not. It has come in at roughly five times my original (2000) budget and has taken far longer than I ever anticipated. While it seems like just yesterday I put down the deposit, looking back, some steps along the way have dragged by agonisingly slowly. Indeed, there were times when the frustration

s The business end. s Testing at Teretonga race circuit.

became so great that I considered pulling the plug on the whole thing, but I’m glad I persevered. To date we have covered a little over 5000 miles in it, with relatively few issues other than what you might expect from a completely scratch-build sports car. However, a quick pre-departure check of fluids, nuts, bolts, catches and hoses is an essential part of every journey.

What’s it like to drive? Much like the originals – very noisy (sounds like a bag of spanners when you hit a bump and the exhaust is very loud), hot, and it leaks like a sieve in the rain. However, the seats are surprisingly comfortable, it has bucket-loads of torque, and it holds the road beautifully. An interested group of onlookers gathers and numerous questions are a given wherever we stop.

A huge vote of thanks to my long-suffering partner Carmen, to Dave Brown for allowing me the flexibility of build to suit my circumstances, to CCD’s team of craftsmen (Neville, Phil, Neil and Petrus) who willingly tackled any problem I presented them, no matter how difficult, and lastly, to John Shand, without whose help the car would likely still be sitting on a build stand gathering dust.

Originally born and bred in Timaru, Brian is a retired marine biologist who lives in Dunedin. He has always been keen on cars and learned how they tick by blowing up his first car, an Austin A30, and having to rebuild it. Rebuilds of a Citroën Big 15 and a MKIII Zephyr followed, simply to get them running better. Other cars of interest have included a Prince B200, MKIV Zodiac, Lancia HPE, Rover SD1 Vitesse, and Sierra Sapphire Cosworth. Brian enjoys working with his hands, and when not tinkering with the GT40, has renovated a 120+ year old Speights home with his partner Carmen, and does realistic oil paintings, some of which feature cars.