4 minute read

EXPLORING MODERN DANCE

Natalie Desch was a dancer with the Limón Dance Company and spent eleven seasons with Doug Varone and Dancers. She was the reconstructor for Dances for Isadora on the women of the company streaming in from Utah via Zoom. We talked with her about the deep meaning behind this work. In restaging this work what do you hope to pass on? Well, I’m somewhat obsessed with the concept of time, and I love the study of history. So I find it thrilling that in 2021, a wonderful group of artists can assemble to embody important chapters of the past. But this doesn’t just mean investigating the trailblazing woman, Isadora Duncan, (1877-1927) who the choreographer, José Limón, (1908-1972) held with such high regard. Yes, we are studying the stages of an individual’s (Duncan’s) life, but we are also studying the philosophies, the zeitgeist of her time, and what personally made her such a visionary––she made seismic shifts in the aesthetics of dance in America and around the world. As well, we have such an opportunity to embody her convictions and her accomplishments through the lens of Limón’s vision of choreography from the year 1971 when he created it. That includes all the personal, political, societal, and aesthetic considerations in existence for him, his dancers, and the greater community at that time as well. It’s a rich opportunity to investigate these chapters of history and how they might also relate to the time in which we presently exist and grapple with the issues in front of us.

The piece was choreographed in 1971 What makes it a classic? I have an admitted bias for Limón’s work, so my answer comes from a very specific perspective! I’ ve had the privilege of learning about him for nearly thirty years–directly from those with whom he worked and from dancing his works first hand. Limón was a consummate formalist in his choreographic design and is especially revered for the magical ways he married musical scores with movement. Dances for Isadora is quite a poetic example of this. Limón captures five distinct eras of Isadora Duncan’s life using an array of piano pieces by Frederic Chopin as well as choosing to leave one solo in silence. These solos display the inherently strong rhythms found in the movement. Through the work, he sculpts both the subtle gestures and the bold physicality of Duncan’s very short-lived but complex life.

Advertisement

Which roles have you danced? I have danced the solo entitled Niobe which was taught to me by Limón company members as part of the audition process when I joined the Limón Company in 1996. It has a special place in my heart because of that. I believe it also has such relevance in 2021 as it speaks to the sadness and loss many people are experiencing as a result of the pandemic. In a tragic chapter of Isadora’s life, Duncan not only lost two young children in an automobile accident when they drowned in Paris’ River Seine (1913) but also lost a child (1914) who didn’t survive infancy. Niobe shares the tender tones of a mother’s grief for the loss of her children and the existential questions that arise when lives are lost.

How would you describe each of the solos?

Primavera – This solo is an exuberant celebration of youth and self-discovery. Primavera shows both a vivacious brightness in an allegro section as well as a thoughtful lyricism in its second section.

Maenad – This solo shows a most sensual side of femininity. With a grounded and strident physicality, we see a character with confidence in her wakening sexuality and sense of self.

Niobe – This solo is a lament––like a mother’s prayer for the loss of her children––sparse and grieving.

La Patrie – This solo is a nod to Duncan’s voice on social and political issues. As a feminist at the dawn of the 20th century, we see her asserting her power and her open-minded beliefs in women’s’ and individuals’ rights and equities.

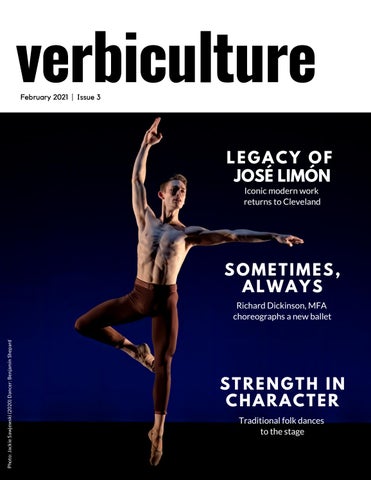

Scarf Dance – This solo is an enigmatic, dreamscape-like chronicle of a life. Its character is briefly revisited by ghosts of prior personalities who help tell this final chapter of life. The dramatic complexities of Isadora are apparent, and her accidental death, when the scarf she was wearing became entangled in the wheels of an Dancer: Sikhumbuzo Hlahleni automobile, are both abstract and haunting.

What strengths do the women of Verb bring to the piece? The artists of Verb possess such incredible depths of understanding when it comes to the subtleties of this work. To put their talents and abilities into perspective, however, some context about process has to be shared. Because of COVID-19 and travel restrictions, I had the unprecedented limitation of NOT being directly in the studio with the dancers as I taught the work. I really doubted whether a Zoom call could reveal the detail and nuance this work requires. However, any anxieties I had about this process were quickly assuaged by the talent and work ethic that were immediately evident! Not only do these women possess virtuosic technique and a mastery of skill in their bodies, but their imaginations and their artistic maturity was pronounced as well. Each woman learned all five of the solos (no easy feat!) and each dancer gave an outstanding and completely unique iteration of each of the chapters of the Duncan story. The women of Verb are a formidable group with the strengths of sensitivity, power, musicality, and theatricality.