16 minute read

First to Vote

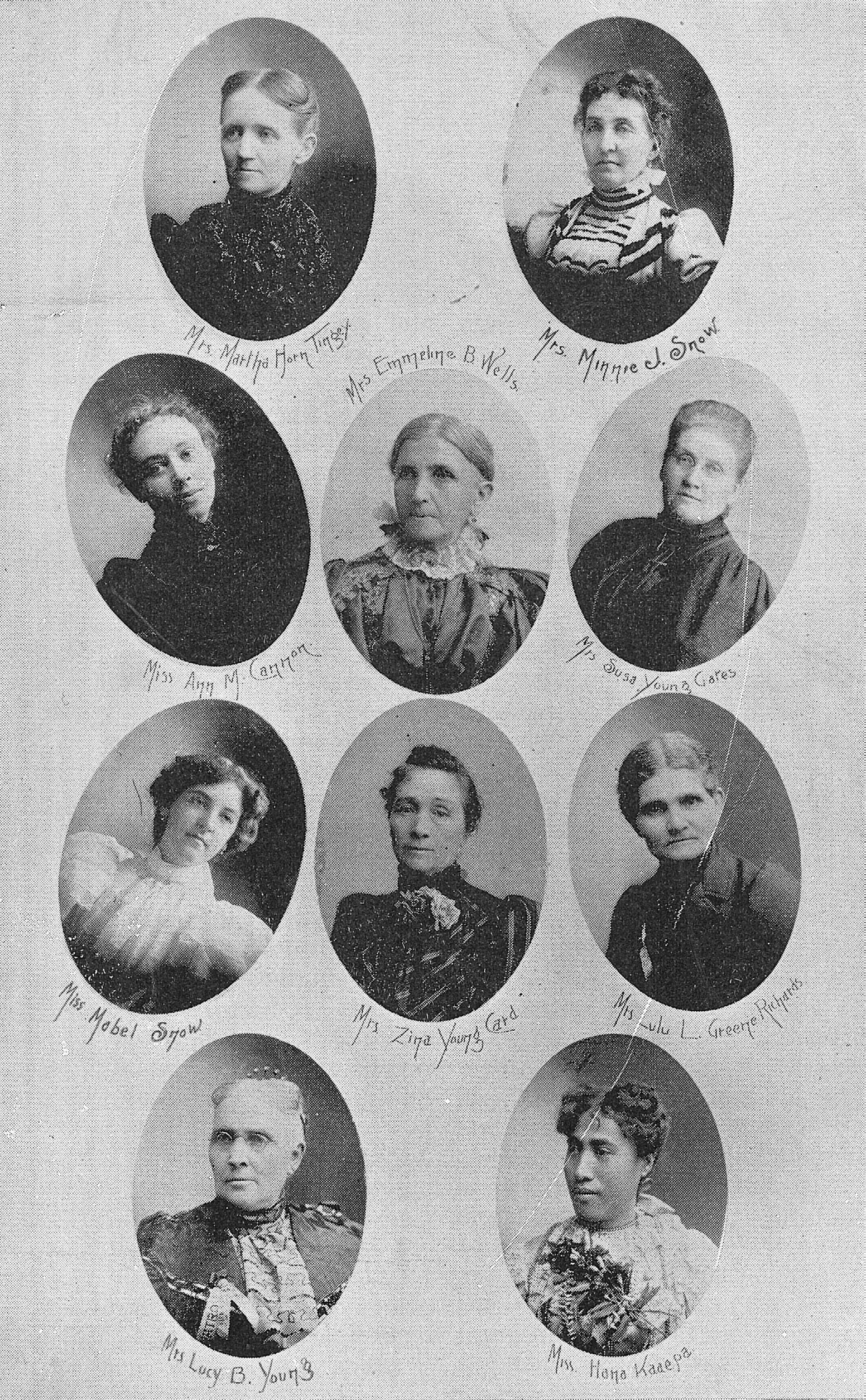

The Utah delegation to the triennial National Council of Women, held in Washington, D.C., in February 1899. Note, particularly, in the bottom right corner, Hannah Kaaepa, a Native Hawaiian woman. Young Woman’s Journal, May 1899.

First to Vote: Commemorating Utah’s Suffragists

BY KATHERINE KITTERMAN

The year 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of Utah women’s first votes: the first cast in the United States under a law that made women’s suffrage rights equal to men’s.1 It also marks the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment and the fifty-fifth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, offering a unique opportunity for Utahns to reflect on the long, messy, and unfinished work for equal suffrage.

Leading up to the Nineteenth Amendment centennial, a resurgence of voting rights history is pulling the suffrage movement back from the sidelines of U.S. history. We’re remembering how—far from being a long but triumphant march forward (for white women)—the movement came to focus narrowly on voting rights, how it split on issues of race, and how various factions negotiated, compromised, or protested to achieve their goals.2 Americans are rediscovering the implications of that movement— with all its fractures, successes, compromises, and setbacks—for our democracy today. We are still wrestling with many of the same questions the suffrage movement raised over one hundred years ago: whose voices matter in the public square, where women fit in politics, business, and community leadership, and how social change should happen.

In 2020, Utahns commemorated the sesquicentennial of women’s suffrage with legislative ceremonies, exhibits, public events, and new monuments. Martha Hughes Cannon will soon represent Utah in the United States Capitol, and a memorial at Council Hall in Salt Lake City now honors the first Utah women voters and all those who followed as federal and state legislation slowly expanded the franchise. From billboards to classrooms, Utahns are rediscovering the local leaders who advanced women’s rights.

In 1970, Leonard J. Arrington remarked it was “fitting” for the Utah Historical Quarterly to highlight women’s contributions in a special issue for the centennial of women’s suffrage in Utah.3 He noted that women in Utah were “the first in the nation to exercise the right of suffrage” and that they were among the first to serve as elected officials. They played crucial roles in many local industries and ran the first women’s periodical west of the Mississippi. Fifty years later, there’s much more to say about Utah’s complex suffrage story and Utahns’ role in the movement for women’s voting rights.

Seraph Young, who became, on February 14, 1870, the first woman in the United States to cast a vote under a women’s equal suffrage law. Reproduced in Deseret Evening News, March 8, 1902.

Utah women citizens became the first in the United States to cast ballots with equal suffrage when they voted in 1870 elections. Their votes attracted national attention and scrutiny, prompting visits from leading suffragists and congressional legislation. The struggle for women’s voting rights in Utah shaped the trajectory of the national movement, and it produced generations of committed suffragists who worked for nearly fifty years to advance a federal amendment enfranchising women.

Despite its historically significant beginning, the story of suffrage in Utah is often relegated to a side note in the national narrative about voting rights history, due to several factors. First, this story played out early. Utah women gained voting rights twice, but in the nineteenth century, before the national movement gained winning momentum or developed a recognizable visual culture. The first suffrage victories in Utah and other western states were crucial, but they became a less-visible prologue to the wins that began accruing more rapidly in the twentieth century. Second, Utah suffragists generally enjoyed support in their work for women’s voting rights from the majority in their communities, especially from Latter-day Saint leaders. There was real opposition to women’s suffrage in some quarters within Utah, but suffragists did not face the same kind of protracted, uphill battle in Utah as they did in most other parts of the United States. This has led many people to conclude that Utah women did not do much to gain the vote.

Third, and most importantly, Utah’s suffrage story has been entangled in the conflict over the Latter-day Saint practice of polygamy from the very beginning. Polygamy was the precipitating factor for Utah’s 1870 suffrage law, and it was the reason Congress revoked Utah women’s voting rights in 1887. It also complicated Utah suffragists’ relationships with various factions of the national movement for women’s rights, well past the official end of polygamy in 1890.4 Unfortunately, many people today write off Utah women’s early political engagement, just like their nineteenth-century contemporaries did, because they consider “the Utah experiment seriously compromised by theocracy and polygamy.”5

The problem with dismissing women’s suffrage in Utah as an experiment or a Mormon public relations ploy is that this obscures the very real political experience Utah women gained as voters and political actors in the 1870s and 1880s. Utah women’s engagement in politics mattered, both to themselves and to other women across the country.6

Utah’s female citizens were the first substantial population of voting women in the United States.7 Their ballots immediately attracted national attention and scrutiny, and as their voting rights became a political football in the conflict over the “Mormon Question,” women both inside and outside the LDS church entered the fray to have their say.8

Latter-day Saint women had collectively entered politics to defend their religious practice and the rights of polygamous men against congressional attack. But within a few years of having gained the franchise, antipolygamists began to target their voting rights as a factor upholding polygamy—or the “liberty of self-degradation,” as the popular nineteenth-century lecturer Kate Field put it.9 The Liberal Party in Utah also attempted to overturn Utah’s women’s suffrage law several times throughout the 1870s and 1880s.10

Many Latter-day Saint women found the need to defend their own voting rights as an equally pressing reason to remain in the political fray; congressional proposals to disenfranchise them came as early as 1873 in an antipolygamy bill introduced by a New Jersey senator.11 They countered antisuffrage arguments nationally and locally decades before those same arguments would be turned on other women as the suffrage movement began to attract organized opposition. Some of the strongest arguments against Mormon women’s right to vote, for instance, developed out the speeches and writings of Utah’s Jennie Froiseth, vice president of the Utah Ladies’ Antipolygamy Society and editor of the Antipolygamy Standard. 12

As Mormon women attempted to defend both polygamy and their voting rights, they adopted and adapted established patterns of women’s political engagement from the antislavery movement and the nascent suffrage movement. Across the territory, they held indignation meetings, petitioned, lobbied, and wrote newspaper articles to counter antipolygamy and antisuffrage arguments. In response to a congressional bill that would have repealed women’s suffrage in Utah, several thousand women petitioned in 1878: “We have exercised the ballot with our own free will and choice, having fully demonstrated that honorable women command as much respect at the polls, as in the drawing-room, the parlor, and the Church.”13 They sought to demonstrate that they were not voting only as their husbands or church leaders directed, but rather that they were capable of rational, intelligent decisions on political matters and that their influence in politics was uplifting, not disruptive, to American society.

Through the course of this political engagement and their defense of their voting rights in the 1870s and 1880s, Mormon women in Utah came to describe and see themselves as citizens.14 This was a meaningful rhetorical choice at a time when the meaning of citizenship was still very much debated in American society. In the early 1870s, the National American Suffrage Association was unsuccessfully trying to demonstrate that (native-born, white) women already held voting rights flowing from their U.S. citizenship.15 At a time when women in other parts of the United States were facing arrest and fines for voting illegally, Utah women were arguing to federal officials that the government was obligated to protect their voting rights as loyal U.S. citizens. Through this engagement, they became articulate political actors in their own behalf.

So what did Utah women do to gain voting rights? First, evidence indicates that Utah women were not the entirely passive observers of the suffrage question in 1870 that some previous historians assumed them to be.16 Minutes from the Salt Lake City Fifteenth Ward LDS Relief Society show that leading Latter-day Saint women passed a motion to “demand of the Gov the right of franchise” at a mass meeting on January 6, 1870.17 That meeting led to the “great indignation meeting” one week later that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich explores in A House Full of Females, and also precipitated similar gatherings in more than fifty towns across Utah Territory. These meetings mobilized over twenty thousand women.18 Utah women did not publicly campaign for the vote in 1870, but their territory-wide mobilization to defend polygamy demonstrated to Mormon lawmakers that women could be valuable political partners. It certainly advanced a goal that some women had felt and expressed privately.19

Three leaders of the women’s suffrage movement in Utah, Emily Richards, Sarah M. Kimball, and Phoebe Beatie, photographed in 1875. Utah State Historical Society, photograph no. 28709.

Later, after Congress disenfranchised all Utah women through the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, Utah women officially organized under the National Woman Suffrage Association to regain the franchise. This effort involved thousands of women across the territory, from San Juan County to St. George, and from Beaver to Brigham City.20 At least twenty-one counties had branches of the Woman Suffrage Association (WSA) of Utah by 1895. As part of this network, suffragists gathered regularly to sing from the Utah Woman Suffrage Song Book, educate each other about civics and current political issues, perform music and recitations, and plan events to sustain local support for women’s voting rights.21 The Woman’s Exponent shared news of local WSA meetings and projects, as well as reporting news of women’s rights and reprinting articles from national suffrage periodicals like the Woman’s Journal and the National Citizen and Ballot Box. 22 Utah suffragists’ careful organization, lobbying, and petitioning secured the inclusion of an equal suffrage clause in Utah’s constitution that also allowed women citizens to hold public office.23

The commitment of Utah women to the cause of equal suffrage did not end with statehood. While the new constitution guaranteed the equal voting rights of male and female citizens, discriminatory U.S. citizenship laws still excluded many women of color from the polls. Women who had emigrated from many Asian countries could not apply for U.S. citizenship until 1952. Many Native Americans were not considered U.S. citizens until 1924, and even then, many states—including Utah—had laws on the books that prevented people living on reservations from voting. The state legislature only repealed Utah’s law in 1957, as a legal challenge was making its way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Elizabeth A. Taylor, who actively encouraged women’s political participation. This newspaper image was preserved by Taylor’s granddaughter, Josephine Taylor Dickey. Courtesy of Amy Tanner Thiriot.

Many women of color in Utah pushed against boundaries of social inclusion to advocate for a fuller realization of equal suffrage. Elizabeth A. Taylor and Alice Nesbitt were particularly active in political campaigns, encouraging their fellow black women to register and vote despite the discrimination they might face in doing so.24 Hannah Kaaepa, a Hawaiian Latter-day Saint, emigrated to Iosepa, Utah, in 1898, the same year the United States annexed Hawaii. At the invitation of May Wright Sewall, Kaaepa addressed the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. in 1899. Speaking in both English and Hawaiian, she urged council members to support the dethroned Queen Lili‘uokalani’s efforts to secure voting rights for Hawaiian women as well as men.25

Between Utah statehood in 1896 and the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, Utahns elected sixteen women to the state legislature and over 130 women to county offices across the state.26 Those numbers would decline in coming decades, but the experience Utah women gained in campaigning, mobilizing voters, and public administration should not be overlooked. The real and practical effects of women’s suffrage in Utah came not only through policies, but also in the way it shaped women’s view of their place in the public square and in the way Utahns marshalled their forces to support national women’s suffrage.

A snapshot simply labeled “Payson 1920” that appears to show women and men queueing at a voting location. Arthur Nichols, photographer. Courtesy of Suzanne Nichols and Jana Warner.

Many Utah suffragists continued their engagement in the national movement for an amendment to the federal constitution. As Martha Hughes Cannon testified in 1898, while serving as the nation’s first female state senator, “none of the unpleasant results which were predicted have occurred.”27 Women from Utah and elsewhere in the West demonstrated that the sky did not fall when women voted. Through the Utah Council of Women, they worked with both the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), as well as the more radical National Woman’s Party. Utahns continued to raise funds, welcome national suffrage leaders, attend conventions, lobby lawmakers, and gather petition signatures in support of suffrage. For example, Utah contributed nearly 40,000 signatures to a massive NAWSA petition for a suffrage amendment presented to Congress in 1910—three times the state’s assignment and one-tenth of the total number of signatures.28 And Utah’s federal delegation were some of the strongest advocates for the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment.”

Utah women punched above their weight in the national suffrage movement, and their experience and contributions shaped the trajectory and ultimate success of that movement in securing a federal amendment for women’s suffrage. The year 1920 was no more the end of suffrage work than 1870 was the beginning, but Utah women’s crucial role in the long struggle toward women’s political equality is worth remembering. Their efforts for the cause of equal voting rights should not be dismissed, overlooked, or forgotten. They supply needed examples of public engagement, careful strategy, and community leadership for Utahns today.

Notes

1. Although Wyoming Territory was first to pass a law extending voting rights to women citizens, in December 1869, Utah Territory passed a similar law two months later, in February 1870. Due to the timing of elections, Utah women were first to go to the polls. They voted in Salt Lake City’s municipal election on February 14, 1870, and in the territory-wide general election on August 1, 1870. Wyoming women first cast ballots in a general election on September 6, 1870. A note on terminology: although nineteenth-century Americans used the term woman suffrage, this issue of Utah Historical Quarterly will use the more accessible women’s suffrage, except in the case of proper nouns.

2. Lisa Tetrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

3. Leonard J. Arrington, “Women as a Force in Utah History,” Utah Historical Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Winter 1970): 5.

4. See Joan Iversen, “The Mormon-Suffrage Relationship: Personal and Political Quandaries,” Frontiers 11, no. 2/3 (1990): 8–16; and Joan Smyth Iversen, The AntiPolygamy Controversy in U.S. Women’s Movements, 1880–1925: A Debate on the American Home (New York: Routledge, 1997).

5. T. A. Larson, “Woman Suffrage in Western America,” Utah Historical Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Winter 1970): 17.

6. Historical work that does take Utah women’s political engagement seriously owes its foundations to research and publications such as Carol Cornwall Madsen’s edited volume Battle for the Ballot: Essays on Woman Suffrage in Utah, 1870–1896 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1997), and her two biographies of Emmeline Wells, An Advocate for Women: The Public Life of Emmeline B. Wells, 1870–1920 (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 2006) and Emmeline B. Wells: An Intimate History (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2017). Also incredibly important is work such as that included in the Utah Women’s History Association’s collection edited by Patricia Lyn Scott and Linda Thatcher, Women in Utah History: Paradigm or Paradox? (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2005) that began to contextualize Utah women’s political participation collectively and as individuals.

7. In 1870, approximately 1,500 women citizens in Wyoming would have been eligible to vote, but that number was nearly 18,000 in Utah by conservative estimates— twelve times larger. See United States Census Bureau, 1870 Census: A Compendium of the Ninth Census, Sex, and School, Military, and Citizenship Ages, accessed April 13, 2020, www2.census.gov/library/publications /decennial/1870/compendium/1870e-27.pdf.

8. Beverly Beeton, “Woman Suffrage in Territorial Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 46, no. 2 (Spring 1978): 6–26.

9. Sarah Barringer Gordon, “The Liberty of Self-Degradation: Polygamy, Woman Suffrage, and Consent in Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of American History 83, no. 3 (December 1996): 815–97.

10. See for example “Proposed Memorial to Congress for a Registration Act for Utah,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 16, 1872, 1; “Utah Gentiles Interview the President on the Polygamy Question,” Eureka (UT) Daily Sentinel, January 30, 1876, 2; “Female Franchise,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, October 2, 1880, 3.

11. “The Frelinghuysen Bill,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, February 18, 1873, 2.

12. For example, in 1880, Froiseth wrote in the Antipolygamy Standard, “The only effect that the franchise has had in this Territory, has been to increase the spread of polygamy and the consequent degradation of woman.” See “Polygamy and Woman Suffrage,” Antipolygamy Standard 1, no. 3 (June 1880): 20. Froiseth was a suffragist herself who served as NWSA vice-president for Utah from at least 1884 to 1888. See National Woman Suffrage Association: Report of the Sixteenth Annual Washington Convention (Rochester, NY: C. Mann Press, 1884), 141.

13. Memorial of Utah Women Against the Christiancy-Luttrell Bills Which Would Disenfranchise Them, March 4, 1878, HR45A-H23.6, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 233; National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.

14. Memorial of Utah Women; “Petition for Woman Suffrage,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, December 19, 1877, 3; Emmeline B. Wells, “Letter to the Sisters at Home,” Woman’s Exponent, April 1, 1886, 164.

15. This “New Departure” strategy hit an insurmountable roadblock in 1875 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Minor v. Happersett that citizenship alone did not guarantee women the right to vote.

16. T. A. Larson, “Woman Suffrage in Western America,” Utah Historical Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Winter 1970): 19; see also, Thomas G. Alexander, “An Experiment in Progressive Legislation: The Granting of Woman Suffrage in Utah in 1870,” Utah Historical Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Winter 1970): 26.

17. “Minutes of a Ladies Mass Meeting,” January 6, 1870, Fifteenth Ward, Salt Lake Stake, Relief Society Minutes and Records, 1868–1968, vol. 1, 1868–1873, p. 139–42, LR 2848 14, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah, available online at catalog.churchofjesuschrist. org, accessed April 17, 2020.

18. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870 (New York: Vintage, 2017); “The Ladies’ Mass Meetings—Their True Significance,” Deseret News, March 9, 1870.

19. The minutes of the January 6 mass meeting were published in the Deseret News along with the call for a large indignation meeting in Salt Lake City’s Old Tabernacle, but the women’s resolution to demand the right of franchise was omitted in that publication. See “Minutes of a Ladies’ Mass Meeting,” Deseret News, January 12, 1870, 8.

20. For a closer look at two local suffrage associations, see Lisa Bryner Bohman, “A Fresh Perspective: The Woman Suffrage Associations of Beaver and Farmington, Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 59, No. 1 (Winter 1991): 4–21.

21. Utah Woman Suffrage Song Book (Salt Lake City: Woman’s Exponent Office, [1890]), LDS Church History Library.

22. For example, see “W.S.A. Reports,” “W.S. Party at Payson, Utah,” Woman’s Exponent, March 15, 1892, 134, and “Women Druggists in Buffalo,” “Notes and News,” Woman’s Exponent, September 15, 1889, 58.

23. Jean Bickmore White, “Woman’s Place is in the Constitution: The Fight for Equal Suffrage in 1895,” Utah Historical Quarterly 42, no. 4 (Fall 1974): 344–69.

24. “Rally of Colored Women,” August 23, 1895, Salt Lake Tribune, 3; “Echoes of the Election,” Broad Ax (Salt Lake City, UT), November 12, 1898, 1.

25. “Hana Kaapea’s Presentation,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, February 26, 1899, 4; “The Recent Triennial in Washington,” Young Woman’s Journal 10, no. 5 (May 1899): 195, 203–204.

26. Katherine Kitterman and Rebekah Ryan Clark, Thinking Women: A Timeline of Suffrage in Utah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), end matter. For information about each of these of these women—compiled by the Utah women’s history nonprofit, Better Days 2020— see “Explore the History,” Better Days 2020, accessed May 20, 2020, utahwomenshistory.org/explore-the -history/.

27. Quoted in Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 4, 1883–1900 (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1902), 319.

28. “Council of Women Has Busy Meeting,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 2, 1909, 12.