11 minute read

Alf Engen: A Son's Reminiscences

Alf Engen: A Son's Reminiscences

By ALAN K. ENGEN

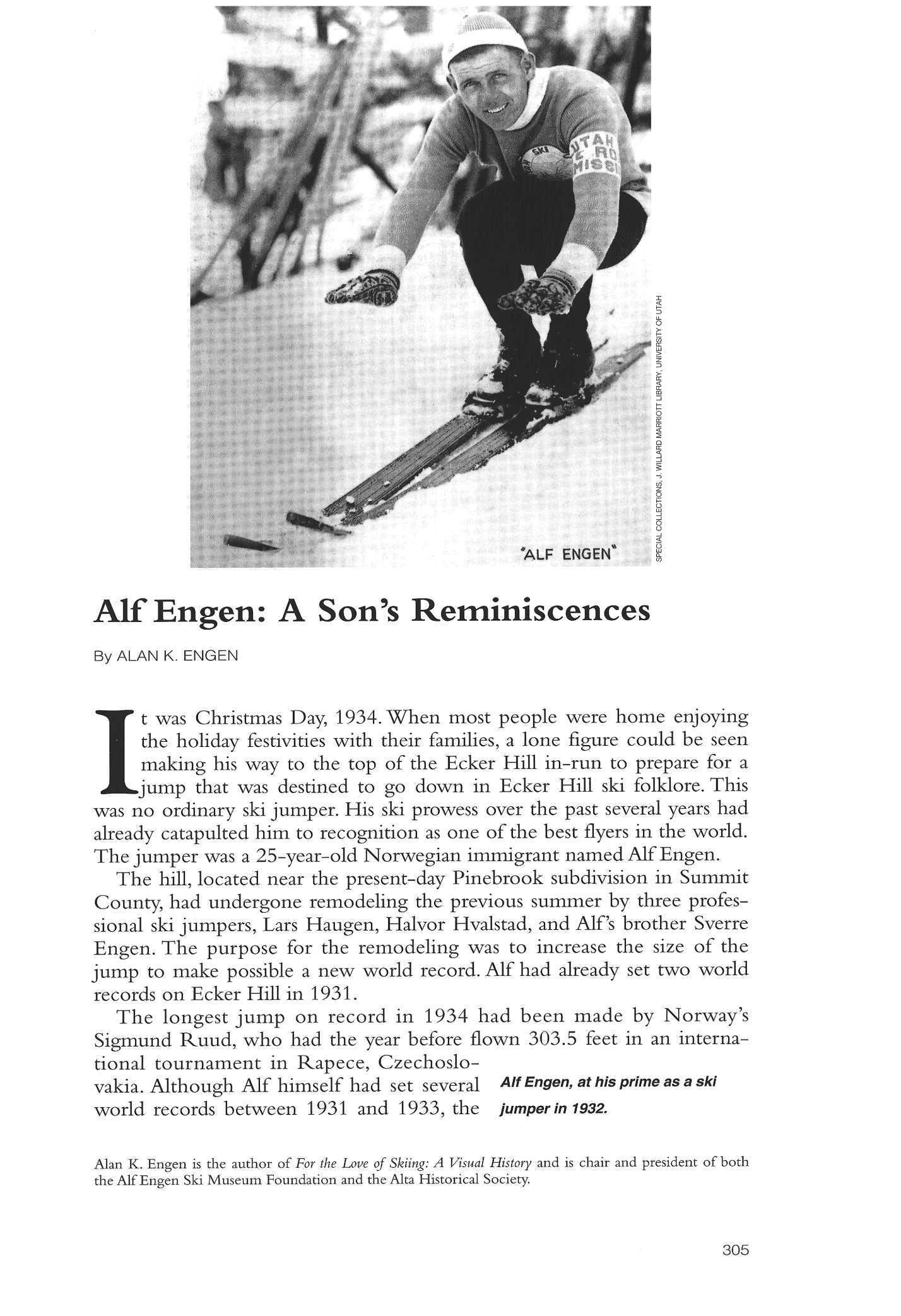

It was Christmas Day, 1934. When most people were home enjoying the holiday festivities with their families, a lone figure could be seen making his way to the top of the Ecker Hill in-run to prepare for a jump that was destined to go down in Ecker Hill ski folklore. This was no ordinary ski jumper. His ski prowess over the past several years had already catapulted him to recognition as one of the best flyers in the world. The jumper was a 25-year-old Norwegian immigrant named Alf Engen.

The hill, located near the present-day Pinebrook subdivision in Summit County, had undergone remodeling the previous summer by three professional ski jumpers, Lars Haugen, Halvor Hvalstad, and Alf's brother Sverre Engen. The purpose for the remodeling was to increase the size of the jump to make possible a new world record. Alf had already set two world records on Ecker Hill in 1931.

The longest jump on record in 1934 had been made by Norway's Sigmund Ruud, who had the year before flown 303.5 feet in an international tournament in Rapece, Czechoslovakia. Although Alf himself had set several world records between 1931 and 1933, the farthest he had gone was 266 feet. He was anxious to see if the elusive 300-foot mark could be obtained on Ecker Hill, which was at the time one of the largest jumps in America.

Alf later said that when he got to the top of the jump and looked down the in-run he knew he was about to go farther than he had ever gone. "I really did not know what to expect because no one had yet tried the hill with the takeoff moved so far back," he told me. "My biggest fear was not being able to judge the speed and possibly out-jump the hill and land on the flat."To land on the flat would cause severe injury.

Sverre Engen said that when Alf raised his hand to signal the start of his descent, all the jumpers at the scene and the hill markers just held their breath. Alf started down the in-run with a running start, gaining momentum that would allow him to approach the take-off at a speed well in excess of sixty miles per hour. His entire body coiled in preparation for the fraction of a second when it would spring up and out, carrying him into space. The jump had to be timed just perfectly to be successful. If he jumped too soon, his flight would be cut short. If too late, the air pressure could tip him over backwards.

The day was clear with no wind. Alf took off, following a trajectory that took him higher and farther than anyone had imagined, causing him to land close to the bottom, or transition, of the hill. The impact, according to Sverre, made a loud cracking sound. When he came to a stop, the markers on the hill yelled to Alf that he had jumped 296 feet, setting a new hill record. That record still stands today as the longest official jump ever made on Ecker Hill.

While this is only one story in a lifetime of experiences of my legendary father, it is the one that answers the question, "How far did Alf go on Ecker Hill?" The following year he flew 311 feet on the hill, but it was only in practice, not in sanctioned competition, so it could not be counted as an officially recognized jump.

Alf was born in 1909 to Trond and Martha Engen in Mjondalen, Norway, a small town approximately thirty miles southwest of Oslo. Being the oldest of three brothers, he had to drop out of school at age nine when their father died of Spanish flu during the Norwegian epidemic of 1919. During Alf's early life, economic conditions were challenging in Norway, and it was hard for him to find work. However, during winter months he always found time to enjoy his favorite pastime, ski jumping, and he was good at it. By the late 1920s he had gained a strong reputation in his hometown as an excellent ski jumper and soccer player. He came close to making Norway's Olympic ski jumping team in 1928. Although he did not make the team, right after the 1928 Olympics he did defeat all the Norwegian jumpers at Konnerud Kollen, a large hill near Mjondalen. Prior to coming to the United States, Alf also finished in the top ten in international competition on the world-famous Holmenkollen Hill in Oslo.

On July 4, 1929, a group of Norwegian immigrants, including Alf, arrived at Ellis Island in time to get a glimpse of the fireworks display going on in the New York harbor. My father told me that he had never in his life seen anything like it and thought to himself, "This must be like what happens in America every day!" Unfortunately, it did not take long to learn that life in the U.S. was not just one big celebration. Shortly after clearing Ellis Island, itself no easy task, Alf made his "way to the Chicago area, as he had been told that a large contingent of Norwegians lived there. He "was able to get a job at Western Electric making holes in metal plates and, later on, a job as a bricklayer's apprentice. As a nineteen-year-old, he found that not knowing the language was a major challenge. He did learn how to say "coffee" and "doughnuts" from some of his associates at work, and those items became his main staple for a brief time.

What eventually led Alf to Utah in early January 1930 was his recruitment into a newly formed group of Norwegian and American ski jumpers. Their idea was to make money by performing extraordinary feats in the air—making long jumps on a pair of twelve-foot-long skis fastened to flimsy boots only by leather straps. It worked; the spectators loved it. There were thirteen members in the original professional ski-jumping group, which included, in addition to Alf and Sverre Engen, Halvor Bjorngaard, Carl Hall, Alf Mathisen, Einar Fredbo, Ted Rex, Steffan Trogstad, Lars Haugen, Halvor Hvalstad, Bert Wilcheck, Sigurd Ulland, and Oliver Kaldahl.

The group came to Utah on a tour. My father often told me that when he first saw the beautiful Wasatch Mountains towering over the Salt Lake Valley he fell in love with this area and never wanted to leave. For the most part, that is what happened; however, during the '30s he did return to the Northeast for a short time to jump in tournaments. He also lived in Sun Valley, Idaho, during the late '30s and early '40s following his 1937 marriage to my mother, Evelyn.

Alf never did compete in the Olympics. He could not compete in the 1932 Games at Lake Placid, New York, because he was a professional, not amateur, athlete (the criteria of the time differed from today's). In 1935 he -was selected for the 1936 U.S. Ski Jumping Team but was disqualified at the last minute because his picture appeared on boxes of Wheaties, the "Breakfast of Champions" and in related advertisements. As he said on numerous occasions, "I never did get any money for it, but I got plenty of Wheaties Everyone in my family had plenty of Wheaties."

Then in 1940 and 1944, the Olympic games were cancelled due to World War II. In 1947 Alf was again selected for the U.S. team but instead chose to honor a special request by the U.S. Olympic Committee that he coach. It is hard to tell what would have actually happened had he competed in the Olympics during his prime, but he was universally regarded as one of the finest ski jumpers in the world during the 1930s and '40s. It is my personal belief that, barring injury, he would have been an Olympic champion.

Besides being an outstanding competitive skier in all disciplines (jumping, cross-country, downhill, and slalom), Alf managed to be featured in several movies, including a Fox Movietone featurette titled Snow Trails in 1941, the Warner Brothers movie Northern Pursuit in 1943, a movie short called Ski Gulls in 1944, and the Twentieth Century Fox movie shorts Ski Aces and Playtime fourney in 1945. In addition, as a representative of the Forest Service, he was instrumental in laying out a number of ski areas throughout the country, particularly in the Intermountain and Pacific Northwest regions. Alta, Snow Basin, and Bogus Basin are but three of thirty-one areas he personally laid out during the late 1930s and early '40s.

Following his coaching experience in the 1948 winter Olympic Games, which were held at St. Moritz, Switzerland, my father moved his family from Sun Valley back to Salt Lake City and took over the ski school at Alta. For the next forty years he ran the Alf Engen Ski School, which still carries his name. During those years he played a key role in developing many of the ski teaching techniques still being used and was mentor to many nowfamous ski professionals such as Junior Bounous, Max Lundberg, Bill Lash, Lou Lorentz, Keith Lange, and others. He was also one of the principals in establishing and running the Deseret News Ski School from 1948 through 1989. Over the years this particular ski outreach program has played a dramatic role in the development of skiers in the Intermountain region. Thousands of people from all walks of life and all age groups have been given the opportunity to learn to ski at very low cost through this program, which was started by my father, Wilby Durham (assistant general manager of the Deseret News), and Sverre Engen.

Alf's awards throughout his lifetime are too numerous to mention. However, some of the more important honors include sixteen U.S. national championship titles (representing jumping, cross-country, downhill, and slalom); the North American ski-jumping title in 1937; world records (he once broke the world record twice in the same day); the coveted Ail- American Ski Trophy in 1940; the Utah Skier of the Century Award in 1953; and election to the Helm's Hall of Fame in 1954, the U.S. Ski Hall of Fame in 1956, the Utah Sports Hall of Fame in 1970, and the Professional Ski Instructors of America—Intermountain Division Hall of Fame in 1989. In addition, he was selected and honored as one of the Founders of American Skiing in 1994, given the Utah Centennial "Once in a Hundred" award in 1996, and was named Utah's Athlete of the Century in December 1999 by the Salt LakeTribune.

In the late summer of 2002, after the Olympics are over, another significant event is planned for Utah. A new facility called the Joe Quinney Winter Sports Center/Alf Engen Ski Museum will open to the public at the Utah Olympic Park near Park City. There, for the entire world to see, will be mementos from Alf's life plus an in-depth look at Utah's many contributions to ski history It is the hope of all those who have dedicated time and effort to this museum that it will indeed be a legacy not only of the 2002 Olympics but also of all the ski legends and pioneers who contributed so much to ski history in the Intermountain region.

Am I proud of my father? You bet I am! But my pride stems not so much from his accomplishments as from the kind of man he was. His passing in the summer of 1997 was indeed a loss for all who knew him. He seemed to love everyone, and people responded to him in kind. Perhaps the most fitting tribute that can be said about my father is what is written on his grave marker:

NOTES

Alan K Engen is the author of For the Love of Skiing: A Visual History and is chair and president of both the Alf Engen Ski Museum Foundation and the Alta Historical Society