10 minute read

Decolonising Academia

By Bea Fones

In order to be truly ‘global citizens’, we must engage with social issues and inequalities. The Café des Arts and Ustinov Seminar teams of the Ustinov Global Citizenship Programme sought to begin this at home, within our own academic community where we, as a team of scholars, wanted to address and dismantle the ways UK Higher Education (HE) has been shaped by colonial power structures. We began planning the ‘Decolonising Academia’ discussion panel late in 2019, rescheduling twice in solidarity with strike action and due to lockdown restrictions. It eventually went ahead in a somewhat different – and certainly new to us – format: as a Zoom webinar in early June 2020!

Advertisement

We wished to challenge the privileging of whiteness that creates an environment where Black, Asian, and Ethnic Minority (BAME) students and staff face institutional racism and enormous barriers to inclusion and academic attainment. It is crucial to keep these conversations at the centre of our work, and use our platforms to combat inequalities within and outside our institutions.

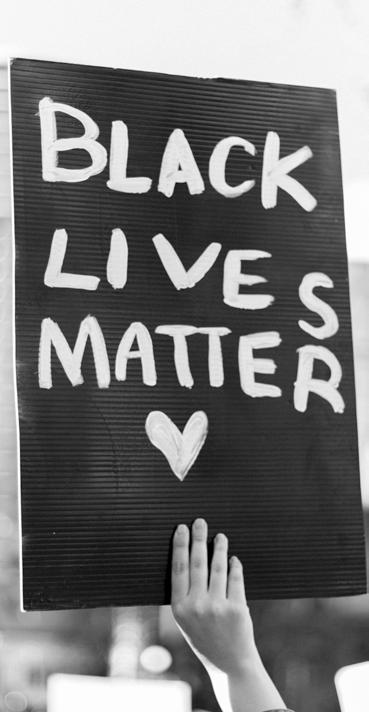

The event fell at a time of increased discussion highlighting the importance of antiracist action, with an enormous global resurgence of #BlackLivesMatter protests days after the death of George Floyd. We began the event with a minute of silence to commemorate the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and all who have lost their lives to police brutality and the violence inflicted on Black communities by structures of white supremacy.

Our panel of speakers joined us from a variety of institutional and disciplinary backgrounds. Dr Jason Arday (JA), Assistant Professor in Sociology at Durham, is a leading voice in the areas of race, education, class, social justice, intersectionality and cultural studies. He is a Trustee of the Racial Justice Network and the Runnymede Trust, the UK’s leading Race Equality Thinktank. Dr Janine Bradbury (JB) is a Senior Lecturer at York St. John University, specializing in African American literature, American Studies, and Critical Race Theory and is a former member of the Runnymede Trust’s Emerging Scholars Forum.

Dr Laura Loyola-Hernandez (LLH) received her PhD from the University of Cambridge and is currently a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Geography at the University of Leeds. She is interested in decolonial thought, feminist political geography, and critical race studies with a focus on Latin America. Mr Kayombo Chingonyi (KC) is Assistant Professor in the Department of English Studies in Durham whose interests are in contemporary poetry, the intersection of poetry and music, critical race studies, black studies, and studies of whiteness with a focus on performativity and lyric subjectivity. His latest book of poetry, Kumakanda, was a Guardian and Telegraph book of the year.

We were lucky to have two guest cochairs joining us for the event. Nailah Haque and Oluwaseun Twins have led Durham University People of Colour Association (DPOCA) as President and Vice-President respectively and are the 2020/2021 Undergraduate Academic Officer and President of Durham Students’ Union.

We were joined by 115 attendees from across the university and further afield for this crucial discussion; we are

enormously grateful for the high levels of engagement, and we hope the event was valuable for everyone who joined us.

We opened with asking panellists what it means to say that academia is colonial and what it would mean to decolonise. Our speakers emphasized that ‘decolonising’ holds different meanings for individuals and communities; it involves the acknowledgment and deconstruction of colonial power structures which erect barriers for BAME staff and students in UK HE. All the panellists articulated the need for pioneering, student-led movements which will bring new ideas to the forefront of the discussion.

JA: ‘I believe white people more generally need to understand what accompanies whiteness; the power, the privilege, the centrality and all it encompasses, and they themselves need to actively destabilise that.’

KC: ‘We cannot do decolonial work out in the world without doing it in centres of knowledge production, and universities are some of the most powerful sites of knowledge production. If the knowledge they produce is decolonial, then we’re doing something important with those imaginative spaces.’

Our panellists work in the arts, humanities, and social sciences; they highlighted how the colonial foundations of higher education manifest in their disciplines, what a ‘decolonised’ curriculum in each of their fields might look like, and how they define ‘diversifying’ and ‘decolonising’.

A potential pitfall of ‘decolonising’ academic spaces arises where the political radicalness of the movement can be lost when the exercise is co-opted and becomes a brand, Laura articulated. Much of the unpaid emotional labour which goes into decolonising efforts is expected of women of colour, Black women especially, in addition to further pastoral responsibilities. Emphasising that normative whiteness is not the centre of knowledge production, Kayombo highlighted that long-term ‘decolonial’ projects can start with short-term moves to ‘diversify’ curricula and institutions. Janine emphasised that students can challenge biases in the lecture theatre, where they feel that what they learn is not reflective of themselves. Panellists also weighed in on the use of acronyms like ‘BIPOC’, ‘people of colour’ and ‘BAME’, which are used widely in academia, policy, and activism. These terms should be approached critically, as while they can bring power in alliance, there is danger in homogenising and reinforcing white supremacy in contexts like the UK, where terms don’t reflect colonial legacies specific to individual ethnic groups. Another key issue was institutional gatekeeping, and how it is an important point of intervention for decolonising practices in academia. What creates barriers for people of colour – especially past the undergraduate level – and how can these barriers be challenged? Our speakers emphasized the role of inherited wealth and social capital which students of colour, and especially Black students, often struggle to access. This fosters an atmosphere where marginalised students must constantly prove themselves worthy, facing additional barriers to studying effectively and benefiting from academic reward systems. Jason drew attention to recent work by Leading Routes, a pioneering initiative aiming to prepare the next generation of Black academics, which investigated the attainment gap for Black students in HE. They found that just over 12% of academics in the UK are from BAME backgrounds, but this doesn’t take into consideration those on precarious, fixed term contracts. Only 32 Black women hold the rank of full Professor in the UK; this illustrates the difficulties for BAME students looking for role models or a ‘blueprint’ for how to succeed in academia. The mental health of BAME students, Laura argued, is not given enough attention; especially in the ways in which it intersects with immigration status, sexuality, gender identity and disability.

We asked our panellists to comment on measures like the Race Equality Charter (REC) and their effectiveness in addressing racial inequalities in HE. Whilst the REC and other measures may be an effective vehicle to engaging in better race equality practice in institutions, panellists responded, they can also become a box-ticking exercise for universities or an opportunity for an optical performance of change. Panellists emphasised the need to work with the community outside our universities, bringing activists, community organisers, and artists with us as contributors

rather than privileging the academic perspective.

Laura pointed to student-led initiatives, like ‘Why Is My Curriculum White?’ led by Melz Owusu in Leeds, as places where some of the most transformative work takes place. Our panellists all highlighted the dangers of ‘decolonising’ being coopted by universities without adequate self-reflection and commitment to supporting colleagues and students of colour who already bear the brunt of organising, mentoring, and additional unpaid emotional labour.

JB: ‘What I would really call for is a radical reconsideration of our spheres of influence, and by that, I mean, where do we want to publish? Where do we want to study? How are we going to get there and is there a way that we can make sure that more people have the opportunity to progress, that is free from institutional funding and recognition and validation?’ JB: ‘I think we just need to be mindful that what we’re doing doesn’t become performative. There’s such a big performative element, especially now with George Floyd, there’s such a scramble to demonstrate how great you are at this, at the cost of doing something genuinely meaningful… Decolonisation has become a new colonised space, and a contested space, and we must fight to protect it.’

With the recent global wave of support for the Black Lives Matter movement, there is a danger this work is not being done in a way which acknowledges how we have been complicit in racism ourselves. Anti-racism and decolonising work must move forward in order to be effective; our panellists emphasised the need to continually interrogate our own motivations. A member of the audience asked panellists to weigh in on how BAME academics can avoid complicity in colonial systems in HE. Our panellists emphasised the importance of keeping an awareness of positionality and privilege, acknowledging and changing behaviours which perpetuate anti-Blackness, supporting others and holding ourselves and others accountable. In response to a question about what students can do to contribute to decolonising efforts, panellists emphasised the significance of holding institutions to account, and taking advantage of the opportunity to give feedback on what they want to see more or less of in their modules and their institutions more widely.

LLH: ‘We do what we can with what we have. Speaking up is difficult, and a lot of the time, the burden comes to students or scholars or activists who are Black or are people of colour. Sometimes, it’s okay to take a step back and take care of ourselves, both as individuals and as a community, to hold ourselves, to elevate ourselves, to love ourselves and to celebrate that… We don’t always have to engage with these conversations because taking care of ourselves is resistance as well.’

Finally, we touched on the topic of how COVID-19 and its disproportionate effects on BAME communities will impact decolonising efforts in HE. Institutional factors prohibiting equal access for BAME communities to housing, education and employment will be intensified. The decolonising agenda, Jason said, should consider the implications of this going forward. For example, Year 13 students transitioning to HE are already disadvantaged by racial biases in that their predicted grades in secondary education (upon which university decisions will be based in the absence of formal examinations) are often far lower than their actual attainment. Factoring in where people attend university, their choices and future employment opportunities, the impacts of COVID-19 on these discussions is something which requires in-depth, nuanced treatment.

As scholars striving to be truly global citizens, we hope the Ustinov College Global Citizenship Programme can continue to be a space where these issues can be brought to the forefront of our work, pushing for equality and the liberation of marginalized people. We will not shy away from acknowledging and working to change the ways we ourselves have been complicit in racism. We hope to continue facilitating these discussions, even when they may be uncomfortable, and commit to providing a space for learning and action, open to the entire Durham University community.

We are enormously grateful to our panellists, chairs, and organising team for all the effort that went into this event, and to our audience members for attending and recognising the significance of this conversation. We hope you will continue to take this journey with us.

By Sorina Avadanei

snegurochka

that patch of sky, staring into my soul with hundreds of eyes and frozen eyelashes

for the first time in my life, i noticed the bridge pillars i noticed they covered the faded red stars

oh, if i could, i would have painted over the whole mountain pour the paint as the snow kept falling the whiteness would be as heavy and warm as my duvet i could fall asleep under it, i could fall asleep for as long as i wanted i could retract into earth’s core close my eyes, and, instead of black i would only see white

but the mountain never did anything wrong