PREMIUM ON SAFETY

ISSUE 53 | SUMMER 2025 IN THIS

Learning From All Operations 3 Small Flight Depts: All Hands on Deck 5 Liabilities from Non-Aviation Hangar Events 10

ISSUE 53 | SUMMER 2025 IN THIS

Learning From All Operations 3 Small Flight Depts: All Hands on Deck 5 Liabilities from Non-Aviation Hangar Events 10

PAUL ‘BJ’ RANSBURY & CLARKE “OTTER” MCNEACE Aviation Performance Solutions (APS)

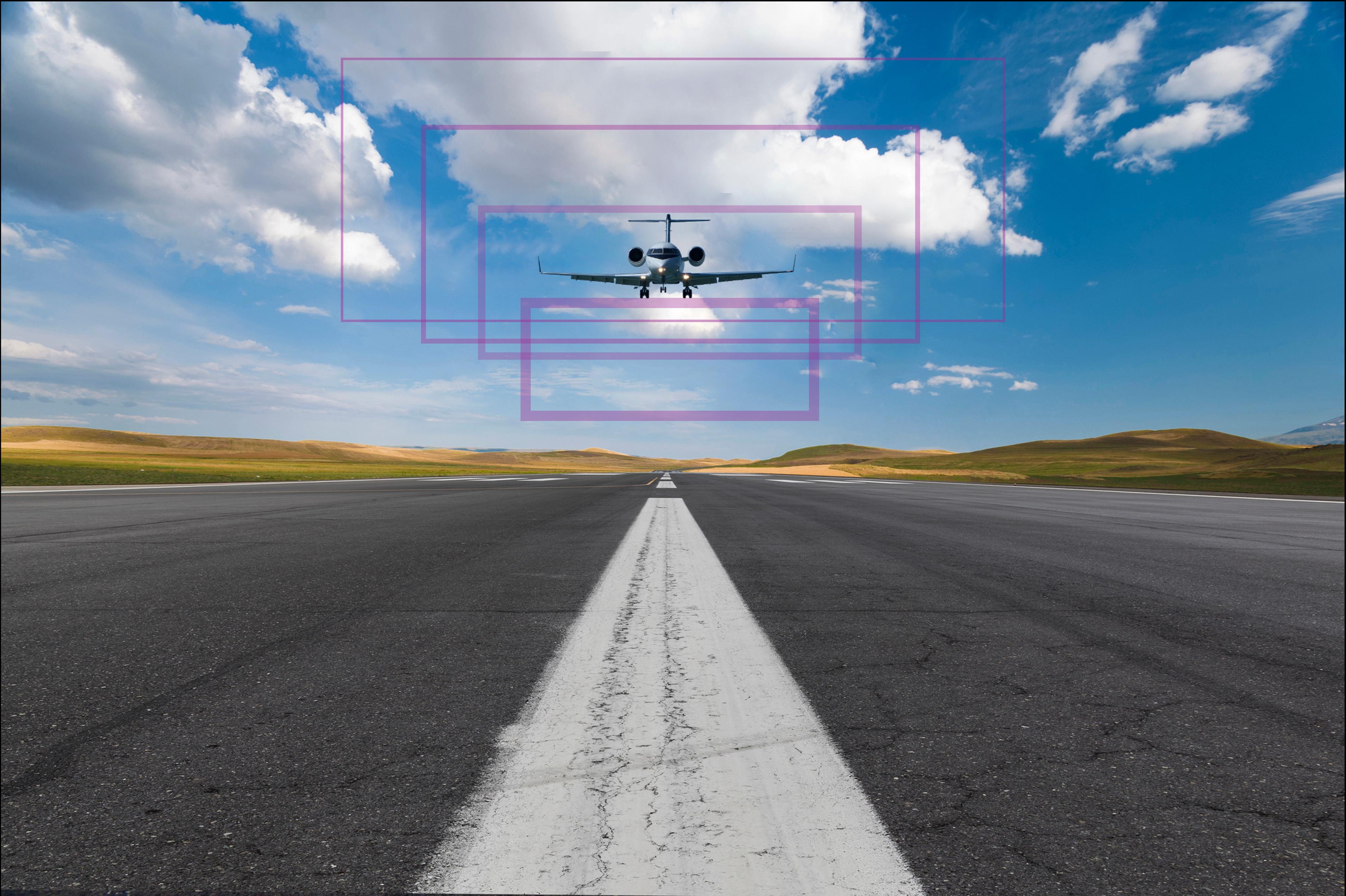

In January 2017, a Bombardier Challenger 604 operating at FL340 over the Arabian Sea was abruptly rolled by a wake vortex from an Airbus A380 passing in the opposite direction just 1,000 feet above. What followed a violent upset, a loss of 9,000 feet, multiple full rotations, serious injuries, and an airframe written off—was not only a testament to the destructive potential of mishandled wake turbulence at altitude, but also a stark reminder of the razor- thin margins and high- stakes decisionmaking required in cruise flight.

For corporate operators, the implications of this event reach well beyond procedural compliance. They spotlight an urgent need to integrate advanced understanding of high-altitude aerodynamics, high-altitude manual handling skills, and strategic navigation techniques into operating practices and training programs.

FAERODYNAMIC MARGINS IN CRUISE: COMPRESSED AND UNFORGIVING

At high altitude, aircraft operate close to their performance limits at much higher true airspeeds. Thrust margins are substantially reduced often 20–40% of what’s available at sea level and aerodynamic margins between stall and MMO can narrow to as little as 10–15 knots. The FAA's Advisory Circular 90-23G specifically warns that this margin compression significantly increases vulnerability to upsets if control discipline is not maintained.

PAUL RATTÉ, USAIG Safety Programs

alse urgency, like that headline tries to evoke, sure creates a lot of mayhem. It opens a bypass from our normal reasoning process, making us far more likely to act in ways counter to our own best interests. No wonder it’s a cyber-criminal’s best friend.

Imagination isn’t needed to see how false urgency haunts aviation. Rushed procedures; landings pressed in poor weather or from unstable approaches; ‘go’s’ that should have been ‘no’s’ are all- too-familiar accident factors.

The 2016 crash of a CJ4 into Lake Erie is a poignant example. Killed were the single pilot operator, his wife and two sons, their neighbor and his daughter. They’d made a 30-minute flight to Cleveland to attend a pro sporting event on an evening between Christmas and New Years, and crashed around 11PM on departure for home after the game. The story’s intrinsically tragic, but the specifics make it even more so. The trip was drivable in ~2.5 hours. The pilot had had just earned his CE-525 rating three weeks prior and had fewer than nine PIC hours in type. Winter precipitation was intermittent at departure, with gusts

to 30 knots. The pilot put in a full workday before the trip, spent the evening at a loud and bustling sports venue bounded by ground transits to and from, and had been awake for over 17 hours at departure. It’s hard not to wonder, with the means to live this lifestyle available: what caused this group to choose the course they did over a hotel, breakfast in Cleveland, and fl ying home in the morning?

Right now you fully see the threat. You shake your head and think, ‘I’d never fall prey to a setup like that. I’m selfaware and always weigh alternatives.’ But you won’t be tested on this while reading a safety article. You’ll be in an Uber laughing with others on the way back to the airport after an event, perhaps with something looming on tomorrow’s schedule, or maybe just motivated to impress or appease someone. You’ll be more tired than you’re admitting. It might be during the year’s most emotionally charged season. Insidiously, getting to pull into your driveway at 1AM becomes the top priority, alternatives notwithstanding and risk be damned.

My fl ying background is in emergency response. Resisting false urgency was a constant theme, with a whole system built to help consistently get to the right outcomes. Even with all that support, this human tendency to sometimes mis -prioritize and take irrational actions happened, spurring regret afterward for choices made. I was fortunate to be able to debrief all of mine.

Don’t wonder if false urgency’s coming for you. The better question is: are you ready to name it (as false), frame it (by maturely developing better options) and tame it (by acting in your own, your passengers’, your industry’s, and safety’s best interests)?

This aerodynamic fragility means that once disturbed, especially by a wake vortex, the opportunity for timely, smooth and controlled recovery is even more critical. The Challenger 604 event tragically illustrated how rapid, aggressive control inputs can compound the problem, leading to secondary upsets and structural failure.

Wake vortices are not only a low-altitude threat, but can have an increased threat footprint at high altitude. At cruise, vortices can descend 1,000 to 1,200 feet and persist for over three minutes in calm air. The lateral spread can exceed five miles. In non-radar airspace with limited separation standards, such as the RVSM environment in which the Challenger event occurred, this wake behavior poses a serious hazard.

Despite procedural compliance, the Challenger crew had no lateral offset option. The airway (L894) did not authorize the use of SLOP (Strategic Lateral Offset Procedure), even though the Mumbai FIR generally published approval. Without the ability to maneuver one or two nautical miles to the right, the crew remained exposed on the airway centerline.

SLOP is not just a procedural formality. ICAO Doc 4444 formally endorses its use to mitigate both collision and wake turbulence risk, especially in oceanic and remote airspace. Where approved, crews should apply a one to two nautical mile right offset, provided the aircraft is equipped with automatic offset tracking. But as the Challenger 604 case demonstrates, authorization is not universal. Corporate flight departments should systematically review airway- specific SLOP permissions and ensure flight crews understand when and how to apply them.

Recovery from upsets at high altitude demands precise yet smooth control movements. The Airplane Upset Recovery Training Aid (AURTA Rev. 2) and ICAO Doc 10011 both stress the importance of recognizing and operating within the margins of energy management. At high

Stay well, fl y smart, and fl y safe. Continues

altitude, recovery often requires counter-intuitive inputs such as unloading to reduce angle of attack, adjusting thrust, and accepting descent particularly when operating in the region of reverse command below L/D max.

Critically, recovery inputs must be tempered. In the Challenger case, aggressive control reactions led to multiple full rotations, inertial reference system failure, and structural overload. Recovery became possible only after the crew regained visual cues, underscoring the importance of resilience, spatial awareness, and training in realistic upset scenarios, which can’t be replicated accurately in a simulator.

The Challenger 604 wake encounter was not a procedural failure; it was a training and awareness gap. For corporate operators fl ying at high altitude in RVSM airspace, this event underscores the need for:

• Routine use of SLOP on oceanic routes where authorized

• Training that incorporates realistic wake turbulence scenarios

• High-altitude on-aircraft UPRT that emphasizes increased stick and rudder skills as well as improved aerodynamic awareness

• Strategic review of routes with wake exposure risks The message is clear: legality does not guarantee safety. Precision, preparation, and prevention keep the crew and passengers safe and secure at cruise.

Paul ‘BJ’ Ransbury, is APS’s CEO and Clarke “Otter” McNeace is APS’s EVP for Compliance and Standards. This article was written in accordance with APS’s content development policy

USAIG is proud that Aviation Performance Solutions is among the participating service providers in our safety programs. For eligible policyholders that apply an annual Performance Vector Safety Benefit toward our Basic Upset Prevention & Recovery Course offer, USAIG covers one pilot tuition to train with the industry’s leading UPRT provider. APS extends further discounts to USAIG policyholders and flexibly applies USAIG’s offer towards advanced course options for those that opt to upgrade their training.

Finding the right resources to support a robust safety program can be daunting. This recurring feature illuminates ideas and resources to help.

KRISTY KIERNAN

Boeing Center for Aviation and Aerospace Safety at EmbryRiddle Aeronautical University

On June 15, 2025, Delta Airlines Flight 1200 from Rochester New York to Atlanta Hartsfield landed safely. So did roughly 26,600 other Part 121 flights, along with about 10,000 business aviation flights. “Routine flight lands safely!” It’s not much of a headline.

As we all know, and probably have told our friends repeatedly over the past few months, aviation is the safest form of transportation. In 2024, we lost 251 people worldwide in commercial aircraft accidents. We killed that same number of people in the first three days of 2024 on American roadways. We got to this point in aviation safety by studying mishaps, incidents, and deviations to find accident precursors and mitigate risks before they manifest into mishaps. We have NTSB investigations, anonymous reporting systems, flight data monitoring programs, threat and error frameworks, and the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System. In short, we have made excellent progress by learning from our mistakes.

But in learning from what we do wrong, are we missing opportunities to learn from what we do right?

Let’s go back to June 15. While those 26,600 flights landed safely, many of those crews faced challenges like unexpected weather, traffic delays, sick passengers, or equipment malfunctions. I know from my own experience - twelve years fl ying in the Coast Guard, and several years of GA fl ying before and after - that there is rarely a day in which absolutely nothing happens. Crews continuously adapt and adjust to keep flights safe. In fact, NTSB and CAST (Commercial Aviation Safety Team) data suggests that pilots intervene to keep flights safe about 157,000 times for every one time pilot error contributes to a mishap. But how much do we really know about what crews do on ordinary flights to keep flights safe and effective?

Continues next page

I got curious about this, which thankfully is part of my current job as a researcher at Embry-Riddle’s Boeing Center for Aviation and Aerospace Safety, so my colleagues and I started asking pilots about recent flights in which something routine but unexpected occurred. Our first hurdle was getting pilots to talk about routine flights. Universally, they thought we were interested in big events – engine failures, fire indications – the kind of thing that happens on the last day at recurrent. It was hard for them to understand that what we really wanted to know about was everyday flights. It turns out that even on flights they considered routine and unexceptional, crews were regularly adjusting and adapting their behaviors, plans, and actions to anticipate and react to changing circumstances.

In systems engineering, this kind of performance is called “resilience”. Resilience means that a system can “adjust its functioning prior to, during, or following events (changes, disturbances, and opportunities), and thereby sustain required operations under both expected and unexpected conditions”.

Resilience doesn’t just happen – it’s a product of four capabilities: specifically, the abilities to plan, coordinate, adapt, and learn.

THE CAPABILITY TO PLAN

One of the pilots we interviewed described getting a TCAS RA while on a visual approach into a busy airport. Earlier, he had briefed his first officer to keep their eyes out for traffic, since he knew the field handled a lot of GA traffic, especially on a pretty Saturday morning. As a result, the instruction to “climb, climb now” did not startle them. In recognizing and articulating the local conditions, he wasn’t following a particular SOP, he was just thinking ahead. This ability to anticipate probable scenarios, think through what might happen, and prepare for contingencies is critical to maintaining system resilience.

Sometimes putting a plan into action requires including other elements in the system. One pilot told us about hearing an aircraft ahead of them on approach getting diverted to an alternate. “We started talking to dispatch and started trying to coordinate to go somewhere else in case we needed to do that,” he reported. The ability to create a shared mental model and communicate effectively makes it possible to enact a plan quickly and seamlessly.

Even great plans sometimes don’t survive first contact with the enemy. That’s true on the flight deck as well –flight crews make plans, but as events unfold, they have to change course and adapt. In a separate study, we interviewed flight instructors, and one CFI told us about fl ying into an airport with significant skydive activity. Although no skydiving was reported in the area, he knew from experience to keep a sharp lookout. Quite suddenly, he saw a parachutist almost in front of his aircraft. Taking the controls, he turned to the “tail” of the parachutist, passing safety behind him. The ability to appropriately monitor the environment and respond to changes when necessary can keep disturbances from turning into mishaps.

Almost every pilot we talked with described knowing what to do first and foremost because of their formal training, but they also described informal learning, through conversation, experience, and observation. The pilot in the previous scenario knew what to do because in that moment, he recalled the words of his own flight instructor for avoiding birds – turn towards the tail of the bird, since they’re unlikely to start fl ying backwards. The ability to learn goes beyond the capacity to recall and apply knowledge – it also includes the ability to reflect upon, build, and share knowledge. One pilot told us, “it’s those little things that you have in your mind of past experiences and past stories that you've heard so that when symptoms of a problem do present themselves to you, you can kind of reach back to those tidbits of information and maybe use that to analyze and figure out what's going on in your situation.”

One of the keys to learning is evaluating and reflecting on past performance. We all know the value of a debrief in the training environment, but in actual operations, how often do we take the time to talk about what we did? We may have good reasons for this – we are tired, we don’t have time, we’re not getting paid for it – but rarely is it because we genuinely had nothing to learn.

The idea that we can learn from all operations is gaining ground in aviation. American Airlines and Southwest Airlines both have formal programs designed to support learning from all operations (LFAO), with many other operators exploring how best to incorporate LFAO into

their training and safety management systems. The Flight Safety Foundation LFAO working group is coordinating efforts worldwide, and has collected several case studies on successful e by NASA, our Embry-Riddle team recently conducted a gap analysis and team resilient performance. Collectively, we are learning how organizations, managers, and concrete steps to increase resilient performance by learning from all operations.

Here are some steps you can take today to increase your own contribution to system resilience, and help your organization build resilience on the flight deck:

• Take a moment, right now, and reflect on the past three flights in your logbook. Although you may consider these flights routine, think about what challenges you encountered. How did you handle them? What prior knowledge helped you? What attitudes and behaviors prepared you? What did you learn that you can apply to your next flight?

• Commit to debriefing your next flight with your crew. Consider adopting the phrase used by United Airlines, “What went well and why?”

• If you are in a management position in safety or training, think about how you can support your flight crews’ resilient performance. Look into systems like CloudAhoy P-FOQA, FlightPulse, or CEFA, all of which provide data feedback for pilots to examine their own routine performance.

• Share this article with your colleagues and get a conversation going. The first step in learning from all operations is understanding that we can learn from our successes as well as our failures.

To paraphrase Marit De Vos of Leiden University, in aviation it’s like we’ve been trying to learn about marriage by only studying divorce. We all know there’s more to professional aviation than avoiding disaster.

Want to learn more? Read Flight Safety Foundation’s excellent primer.

Kristy Kiernan, Ph.D., is the Associate Director of the Boeing Center for Aviation & Aerospace Safety

JENNY SHOWALTER

I started working at my family’s former FBO in Orlando in the mid-90s during college and joined the business full time in 1996. I still remember the buzz of hosting our first National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) Static Display. Our ramp was literally overflowing with light and mid- sized jets, and the Falcon 900 and Gulfstream GIV stood out as the heavyweights. That was also the year the Global Express made its debut, ushering in the era of ultra-long -range jets that now seem like old news.

Back then, and still today, Orlando’s business aviation scene reflected what the data tells us: small operators are the heart of our industry. According to NBAA, members operating one or two aircraft make up roughly 80% of the association’s membership. That includes a significant number of owner-flown and single-pilot operations. Recent years have seen a rise in individual aircraft ownership paired with outsourcing to management companies. These organizations help bridge gaps by providing access to dispatch, HR, chief pilots, and other support roles, easing some of the burden on small flight department teams.

Continues next page

Although many benefit from that type of managed support, there are still plenty of stand-alone departments, and the day- to-day experience of a small operator remains distinct. As the wife, daughter, and sister of pilots fl ying for single-aircraft Part 91 operations, when I talk about the small operator experience, I’m not looking from the outside in. I’ve lived it. And in my work today as a business aviation career coach, I hear the same themes echoed by professionals working in these lean, high- trust environments.

It’s easy to center conversations about safety around larger, more resourced flight departments. They have the structure, staff, and funding to make safety a dedicated function. But small operators? They operate with fewer hands and more shared responsibility. When one or two people are managing dispatch, scheduling, catering, maintenance oversight, and operational control, not to mention fl ying, the margin for error shrinks fast. There’s a reason the phrase “many hands make light work” exists. In small operations, the opposite is often true. Everyone is doing more with less backup. Safety, no matter how important, can get pushed aside, like skipping a debrief or deferring a minor issue to save time.

Aircraft have evolved. The demands have multiplied. But the team size? Too often, it hasn’t. Fast forward from when I joined the industry to today, and aircraft are bigger, faster, and capable of fl ying farther than the human body or a two-pilot flight department can realistically keep up with. The demands on small teams have grown, but the team size hasn’t. For many, it’s still the same handful of people trying to meet every operational, regulatory, and customer expectation without dropping a ball. That’s where fatigue and burnout show up, and when they do, safety can be the first to feel the impact.

If the phrase “Take vacation while the plane is in maintenance” sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Small operators are often on a short leash, expected to be available 24/7/365. Constant readiness might feel like part of the job. But over time, it chips away at quality of life, and safety. Growing up in aviation, I was trained from a young age for this lifestyle. I learned early on that my dad’s primary role was to be available for work,

even when it was inconvenient. My dad, brother, and husband are among those who still live on call. Whenever we’re making plans, my husband always gives the caveat, “subject to change,” and I know I may have to handle things on my own if he gets called in.

This constant state of readiness isn’t just tiring. It lessens your ability to stay sharp. When time, focus, and mental clarity disappear, so can the ability to consistently make safe decisions. Many of my coaching clients are professionals from small flight departments who open up about these same challenges. The pressure to always be available. The unspoken expectation that if you “haven’t flown in two weeks, you must be rested and ready,” even though you’ve been “on standby” the entire time. It’s a dynamic that wears on even the most dedicated team member. The mental load of being perpetually prepared creates a quiet strain that doesn’t always show up in logbooks, but it shows up in decision fatigue, strained communication, blurred roles, and safety shortcuts made under pressure.

That strain can also show up in how leadership functions, or struggles, in small departments. If you're running a single-pilot operation and relying on steady contractors, it’s usually clear who’s in charge. But in a two-pilot operation, where both pilots are equally trained and typed, leadership can get murky. And when a principal is involved, the pilot in charge often serves a dual role, managing the relationship with the aircraft owner while also leading the team. That responsibility requires clear communication, not just with the principal, but within the department, to ensure aligned expectations.

When one of you leads on paper, but you operate as equals, it can build a strong, respectful rhythm, or create quiet tension. That relationship can be difficult to navigate if the lines of communication aren’t open. Without clarity and trust, even the best-intentioned teams can find themselves off balance, and that uncertainty can spill into the way decisions are made and how risks are assessed.

I also hear about issues that go beyond structure. Things like eroded standards or relaxed norms, simply because the relationships are too close, and the same two or three people are always fl ying together.

Familiarity can breed assumptions. Pre-flights, debriefs,

Continues next page

reporting, SMS participation, and other safety practices start to slip, not out of neglect, but out of habit. It becomes easy to believe you're operating safely simply because you know each other well or because 'this is the way we’ve always done it.' But without structured checks and balances, those assumptions can create blind spots, and in aviation, blind spots are vulnerabilities.

This is where professional development, training, and staying connected to industry best practices come into play. It’s important, especially for small teams, to develop team members outside of your organization, so they gain perspective. Exposure to how others operate provides a useful contrast that helps identify what’s working, what’s missing, and what may have become too familiar. Sometimes the safest thing you can do is step outside your own bubble. I know, it’s easier said than done. But for small operators, making time for growth isn’t optional. It’s essential.

Small operators are the backbone of our industry. But they carry heavy, often hidden burdens that deserve more attention. That’s why it’s worth stepping back and asking the hard questions: Are we doing everything we can to keep safety front and center? Are we speaking openly about the pressures our teams face, and addressing the risks that come from familiarity, fatigue, or unspoken expectations?

For small flight departments, there’s no safety department to pass the responsibility to. It lives with every member of the team, especially leadership. Taking a fresh look at internal communication, professional standards, and principal expectations isn’t just the best practice. It’s a safety imperative. Because when resources are limited, clarity, consistency, and open dialogue become your most important tools.

The National Business Aviation Association maintains a Small Flight Department Subcommittee focused on the challenges raised in the article above and more. Check out the many resources and articles developed specifically for small flight departments and available on NBAA’s website using the link to the right.

Jenny Showalter is a third-generation business aviation professional and founder of Showalter Business Aviation Career Coaching (SBACC). With nearly 30 years of experience, she helps industry professionals strategically elevate their careers through individualized coaching, resume writing, interview preparation, LinkedIn optimization, and outplacement services. Jenny’s aviation expertise and

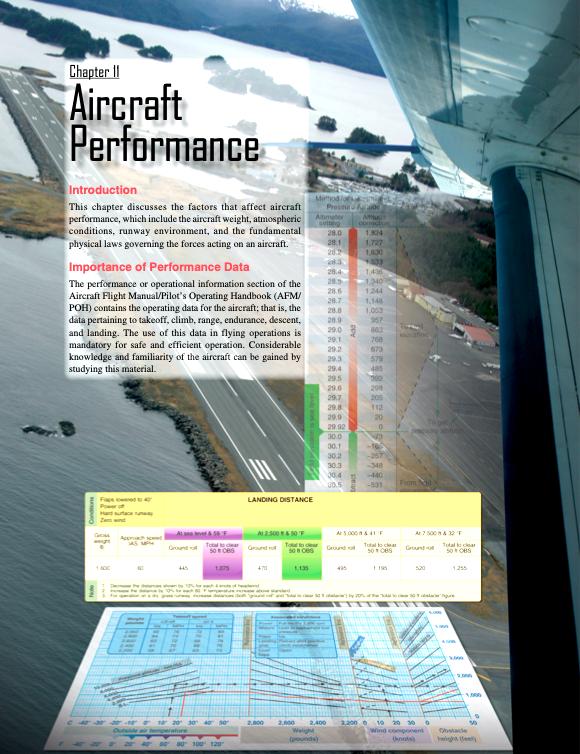

TAdvanced Aircrew Academy’s Aviation Challenge

raining on Aircraft Performance is crucial year-round, but its importance becomes even more pronounced during the warm weather months. High temperatures reduce air density a "high-density altitude" condition that directly affects aircraft engine performance, aerodynamic lift, and overall operational capability. Without proper training, crews may miscalculate takeoff or landing distances, climb gradients, or weight limitations, leading to increased operational risk. Comprehensive performance training ensures pilots understand how to interpret Aircraft Flight Manual (AFM) performance charts and apply correction factors for temperature, elevation, and runway conditions. It also equips crews with the skills to assess real- time airport and environmental data to make informed, safe decisions during critical phases of flight.

Warm weather operations often coincide with other complicating factors, such as higher passenger loads, longer flight legs, convective weather, and reduced runway lengths due to construction or increased traffic. These challenges amplify the need for precise takeoff and landing performance planning and awareness of regulatory requirements and airport- specific considerations. Training programs focusing on TORA, TODA, ASDA, LDA, and Part 25 certification standards prepare flight crews to navigate these conditions effectively. Pilots trained to analyze performance data and apply operator- specific procedures and operational specifications are better equipped to mitigate risks, comply with regulations, and maintain the highest flight safety standards even in demanding summer environments.

Here's a quiz to trigger some thinking about summer fl ying factors: (answers on page 14)

1. Pilots must ensure their aircraft will meet at least the minimum certification performance requirements to _________________

a. Avoid obstacles

b. Meet TERPS criteria

c. Comply with FAR Part 135 requirements

d. Comply with the AFM and be legal

2. AFM certification performance limitations ensure you can also meet FAR Part 91 and 135 operational regulatory requirements.

a. True

b. False

3. FAR 135.379 requires limiting the takeoff weight to meet obstacle clearance requirements. The net flight path must clear obstacles by at least _______ feet vertical clearance or 300 feet lateral clearance after passing the airport boundary.

a. 35

b. 50

c. 100

d. 200

Quiz continues next page

Advanced Aircrew Academy—a USAIG Performance Vector participating service provider—offers comprehensive eLearning modules and curricula for business aviation professionals. Customized online courses, training materials, and scenariobased training improve crew skills in areas such as crew resource management, emergency procedures, and operational effectiveness. Their extensive and adaptive training catalog has eLearning for every person in your flight department.

4. _____________________ is the runway plus or minus stopway length available and suitable for an airplane aborting a takeoff

a. Accelerate Stop Distance Available (ASDA)

b. Takeoff Run Available (TORA)

c. Landing Distance Available (LDA)

d. Takeoff Distance Available (TODA)

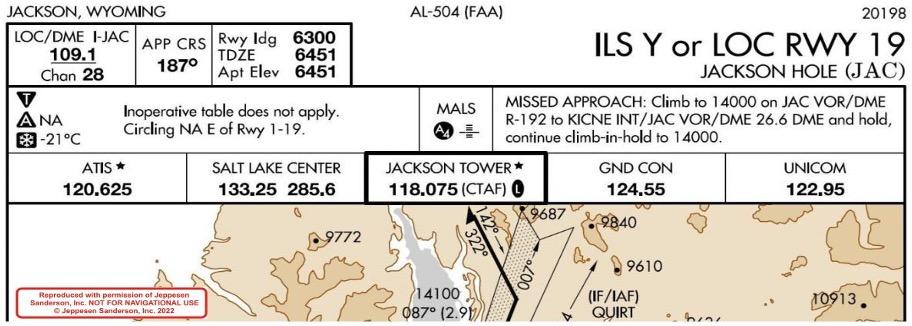

5. The Landing Distance Available for the ILS Y or LOC RWY 19 at JAC is _____________.

a. 6451 feet

b. Not shown

c. 6300 meters

d. 6300 feet

Quiz answers on page 14

Want a deeper dive on summer fl ying topics?

Consider Advanced Aircrew Academy’s Weather Radar training module and/or a review of the Aircraft Performance chapter in the FAA Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge

DANIEL FERGUSON, ESQ., USAIG VP, CLAIMS

Hangars and aviation premises are increasingly being repurposed for more than just aircraft—think luxury car storage, RV maintenance, boat detailing, and even highprofile social events. While these uses can increase principal and employee satisfaction and generate community engagement, they also introduce a host of potential first-party and thirdparty exposures that may fall outside the scope of traditional aviation insurance policies.

As aviation facilities increasingly host non-aeronautical activities, ranging from vehicle storage and maintenance to large- scale social gatherings, the legal landscape surrounding their use is becoming more complex. When a hangar transforms into a venue for a corporate dinner, charity auction, or private celebration, the risks extend far beyond traditional aviation operations. These events and activities introduce new exposures, such as unfamiliar guests, temporary obstacles, alcohol service, and increased foot traffic. Each of these factors can lead to injuries, property damage, and/or regulatory violations. Without clear procedures, proper contractual protections, and insurance coverage aligned with these activities, operators may find themselves facing liability and/or uninsured losses for incidents that fall outside the scope of traditional aviation risk.

Hangars and aviation facilities are no longer used exclusively for aircraft storage, maintenance, and operations. Increasingly, they are being used to store vehicles such as cars, boats, and RVs, and to perform maintenance or detailing work on non-aircraft assets. While these uses may seem like practical extensions of available space, they introduce a new category of risk that aviation operators may not be fully prepared to manage under existing policies and procedures.

The non-aeronautical use of aviation premises brings with it a range of legal liability exposures. The space available in a hangar may appear to be a logical place to prepare a boat for the season, detail a prized car owned by a pilot or principal, or even park vehicles used by passengers while

they are away. However, these uses of aviation space can invite potential losses. Often, such non-aviation activities evolve into multi-day or even multi-week arrangements. A space once reserved for the open movement of aircraft becomes a cluttered environment filled with sporadic vehicles and equipment unrelated to aviation operations. In such cases, a minor misstep could result in costly damage to an aircraft or other property. The owner of the non-aircraft vehicle may also expect compensation for any damage incurred, creating a dual liability scenario.

Additionally, the presence of non-aviation equipment and materials increases the risk of fire and other hazards within the hangar. The introduction of flammable fluids, battery-powered devices, or improperly stored materials can significantly elevate the risk profile of the facility. These risks are often not contemplated in the original design or insurance coverage of the hangar.

Perhaps the most visible and potentially hazardous nonaeronautical use of aviation facilities is the hosting of public and private events. Hangars are increasingly being repurposed for fundraisers, receptions, and community gatherings. Of all the potential pitfalls associated with such activities, premises liability is a significant concern. When members of the public are invited onto the premises, the operator is often alleged to have assumed a duty of care. Uneven flooring, unsecured equipment, or inadequate lighting can lead to slip-and-fall claims or other alleged injuries. If the event extends beyond the hangar, conditions on adjacent outdoor spaces, such as ramps or parking areas, can also result in injuries or vehicle accidents.

These events also introduce risks that are outside the control of the aviation operation itself. Vendors and contractors involved in setup, teardown, or event execution can create liability exposures that may ultimately be attributed to the facility operator. If alcohol is served, liquor liability becomes a significant concern, particularly if service is not handled by a licensed and insured third party. Even well-intentioned hospitality can lead to serious consequences if a guest is injured or causes harm after consuming alcohol at the event.

To manage these risks, aviation departments must take proactive steps. The most effective way to avoid such exposures is to prohibit non-aviation activities at aviation facilities altogether. However, if such activities

are permitted, risk mitigation and transfer strategies should be strongly considered as they can be critical in terms of managing the corresponding exposure(s).

Strong contracts are often essential to managing liability. Agreements with vendors, event organizers, and storage clients should often include hold harmless and indemnification clauses that shift liability away from the aviation operator. These contracts should also often provide for the furnishment of certificates of insurance from all third parties, including caterers, entertainers, and equipment providers, with respect to the insurance protections that the contracts require such third parties to procure for the operator. Waivers of subrogation should often be included to prevent the third parties’ insurers from seeking recovery from the operator after paying a claim. It can also be important to clearly define operational control and assign responsibilities for safety, security, and emergency response in such agreements.

In addition to contractual protections, aviation departments should consider implementing a range of risk management best practices. Pre-event safety walkthroughs can help identify and mitigate hazards before guests arrive. Access control measures can also be used to restrict entry to aircraft, maintenance areas, and other sensitive zones, including areas that may contain Sensitive Security Information as defined by the Transportation Security Administration. Emergency planning should often include coordination with local fire departments, EMS, and law enforcement, as well as the establishment of evacuation routes and communication protocols. Security measures such as signage, barriers, and designated personnel can help guide guests and protect high-value property. It can be important to have staff and volunteers trained on safety procedures and emergency protocols as well. After the event, operators should consider conducting a postevent review to document any incidents or near misses and use the findings to improve future planning.

Insurance coverage should also be carefully reviewed. Many aviation insurance policies are not designed to cover activities that are not directly associated with aviation operations. Operators should consider working closely with their insurance brokers and underwriters to identify potential gaps in coverage. Aviation premises liability coverage may not extend to non-aircraft property or activities. For example, damage to a stored car or injury during a non-aviation event may fall outside the policy’s intent.

Common exclusions in aviation policies include fire damage to rented premises unless specifically endorsed, consequential damages such as loss of use or business interruption, off-premises automobile use, and liquor liability. Coverage for medical expenses related to injuries on the premises may also be limited. Before permitting any nonaviation activity, it is important to coordinate with insurance professionals to understand what coverages are available and where exclusions may apply. In some cases, a separate special event policy or endorsement may be necessary to ensure adequate protection.

Using aviation facilities for non-aeronautical purposes, especially as event venues, can be a meaningful way to engage with the community and make use of available space. However, these activities come with a unique set of legal and insurance challenges. By understanding the exposures, reviewing insurance coverage, and implementing strong contractual and risk management practices, operators can protect themselves from liability and ensure that their facilities remain safe, compliant, and well-managed regardless of how they are used. ❖

DAVID JACK KENNY

People aren’t perfect. If they were, there’d be little need for the National Transportation Safety Board (or bankruptcy courts or marriage counselors, for that matter). When the stakes are high, multiple layers of safeguards are needed to protect us from the consequences of human imperfection: mechanical redundancy and rigorously constructed instrument procedures come to mind. And while their repeated invocations by advocates and company brass may start to seem repetitive, formal safety management systems (SMS) informed by flight data monitoring (FDM) can be crucial to catching individual failures before they explode into catastrophes.

On occasion, the NTSB has explicitly cited the lack of SMS and FDM programs as having contributed to causing crashes, as their absence deprived the operators of the chance to identify troublesome behavior in time to correct it. One example took place before dawn on an autumn morning in eastern Georgia.

Lessons Learned

International Airport about an hour later to pick up freight that was still en route to the airport. Their second leg, to the Thomson-McDuffie County Airport (HQU) in Thomson, Georgia was delayed for about two hours and 20 minutes. They took off again at 2:09 Central Daylight Time (3:09 Eastern).

At 5:03 Eastern time one of the pilots asked the Atlanta Center controller for “any information” about NOTAMS for the ILS approach to HQU’s Runway 10. The controller responded that one NOTAM indicated “GP – but, uh, we do not know what GP means – and then slash US, unserviceable.” “GP” was a reference to “glidepath,” or more familiarly “glideslope,” but the pilot on the radio merely replied, “Roger.” A second controller analyzed another NOTAM indicating that the localizer would also be out of service but correctly determined that it would not go into effect until 12:00 GMT (8:00 local time), more than two hours after they expected to land.

Overnight cargo flights were a familiar assignment for the 73-year-old captain and 63-year-old first officer, who had frequently flown them together. Their first leg of the night began at 21:32 local time on October 4, 2021 when they departed from their base at the El Paso (Texas) International Airport in a Falcon 20C. They landed at the Lubbock (Texas) Preston A. Smith

An advisory for thunderstorms was in effect, and there were storms to the west and north of HQU. The controller warned that his radar was “showing some moderate heavy extreme precipitation just west of the Atlanta VOR all the way to Atlanta” and the pilot replied that they’d “stay up here” at FL350 “as long as we can.” At 5:18, after apparently listening to HQU’s AWOS broadcast, the captain commented, “There’s gonna be lightning all around us.”

The first officer was the pilot fl ying. Between 5:18 and

5:25, the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) captured the captain repeatedly chastising him over deviations in altitude and heading, telling him three times to “fl y the airplane” and once, “Just fl y the damn airplane.” At one point the captain took the controls himself. Noting that they were “going through an area of storms,” he asked, “You’ve flown in bad weather before?” For over a minute, he repeatedly told the first officer to turn left 15 to 20 degrees to get onto their assigned heading of 130 degrees. After running the descent checklist, he interrupted his approach briefing to give the first officer another heading correction.

At 5:25, as the flight descended from FL 240 to 15,000 feet, an Atlanta Center controller warned them that “you’ve got an area of heavy to moderate precipitation present position, extends parallel to the field” and asked for their approach request. The captain requested the ILS to Runway 10 and was cleared to CEDAR, the initial approach fix, then direct to the field. It took the pilots some six minutes and the assistance of the controller to correctly identify CEDAR, an NDB with the identifier “AA.” During that time the captain warned the first officer about another impending altitude deviation and again told him “You fl y the damn airplane,” adding, “I don’t want you to kill me.”

Neither the crew nor the controller noted that the glideslope was out of service, making this a localizer approach. At 5:37 the controller advised they were 15 miles southwest of CEDAR and instructed them to “cross CEDAR at or above three thousand, cleared for the ILS localizer 10 into Thompson-McDuffie.” The captain, transmitting on the guard frequency, read it back as “cleared for the ILS” and was told that was a “good readback” and to “report back established on the procedure.” At 5:39, the captain said, “Would you fl y the airplane, man … I’ve been doing everything else,” then told the first officer to “fl y the ILS,” then, 40 seconds later, to “follow the glideslope without that.” “Loc[alizer]’s alive” was called out 28 seconds later.

ADS-B data showed that the Falcon passed CEDAR inbound 600 feet high and 500 feet left of Runway 10’s extended centerline at a groundspeed of about 165 knots. At 5:42:40 the captain transmitted that they were on the localizer, had the runway in sight, and cancelled IFR. The Falcon continued to descend about 600 feet above the three-degree visual descent path and deviated further to the left as the captain repeatedly warned the first officer, “We’re high and fast…you gotta lose 20 knots here.”

At 5:43:35 and again at 5:43:59, the captain instructed him to “use your air brake.” Four seconds later he said, “Now you’re low,” and two seconds after that “You’ve got trees.” The stall warning sounded just before the recording ended with two distinct sounds of impact. The “heavily fragmented” wreckage was subsequently found about three-quarters of a mile short of the runway threshold, 880 feet beyond the initial point of impact in 150foot pine trees. Both pilots were killed. Investigators found the landing gear down and both flaps and air brakes fully extended.

Continues next page

Well defined and implemented stabilized approach criteria are a cornerstone of consistently safe approaches and landings. A well integrated SMS paired with an FDM program provides the best means to assure your stabilized approach criteria are well defined and implemented.

The investigation revealed problems more extensive than the obvious failures of airmanship. The captain had logged nearly 12,000 hours that included 1,665 in make-and-model, but on several occasions had required additional training to pass required competency/proficiency checks. The check airman’s notes from a December 2017 DA20 simulator session noted that during instrument procedures, he was “cleared for right turn by ATC, mis - set hdg bug resulting in left turn. Distraction resulted in loss of airspeed to full stall condition.”

The first officer claimed 10,900 hours of flight experience and had flown SIC in Falcon 20s since 2009 but had never been upgraded to captain “due to pilot performance and a lack of aeronautical decision making and airmanship necessary to become a PIC/captain.” The operator reported that the two had been paired “for several months.” The accident flight was their fifth together in seven days.

Subscribe to Premium on Safety, view past issues, or share your comments, questions, and general feedback with USAIG

The Falcon 20’s approach checklist calls for the air brakes to be retracted, and the CVR recorded the confirmation of “airbrakes stowed” as the crew completed the approach checklist. The airplane’s aircraft flight manual prohibits extending the air brakes during approach if flaps are extended unless the anti-ice system is in use, and then only down to 500 feet AGL with approach speeds increased by 10 knots. Weather data didn’t suggest that the flight encountered icing conditions, ice wasn’t mentioned on the CVR recording, and a sound spectrum analysis found no evidence that ice protection was in use. Dassault representatives told investigators that “no data … existed as to what flight characteristics the airplane would demonstrate in an idle power, full landing flaps, landing gear down, and air brakes deployed configuration.”

According to the operator, the CVR tape revealed several violations of their standard operating procedures, including the captain’s failure as pilot monitoring to make altitude callouts at 1,000, 500, 100, and 50 feet AGL during a visual approach and both pilots’ failure to call for an immediate go-around when the approach remained unstable at 500 feet. At the time, the company did not have an FDM plan, and their formal SMS was described as “at the development stage.”

While the accident’s probable cause was “the continuation of an unstable dark night visual approach and the captain’s instruction to use air brakes … contrary to the airplane operating limitations,” the NTSB also cited “the operator’s lack of a safety management system and flight data monitoring program to proactively identify procedural non-compliance and unstable approaches.” With no information on this crew’s cockpit discipline, the company saw no reason to tighten their procedures. ❖

Premium on Safety is published by United States Aviation Underwriters (USAU) as managers of the United States Aircraft Insurance Group (USAIG) ©2025.

USAIG

AMERICA’S FIRST NAME IN AVIATION INSURANCE

125 Broad Street, 6th Floor New York, NY 10004

212.952.0100 | usaig.com

Publisher: John T. Brogan

President & CEO, USAIG

Editor: Paul S. Ratté

Your feedback is vital to our safety programs because it helps us focus on what’s most important to you. USAIG’s website (USAIG. com) offers a convenient way for us to receive your thoughts or suggestions. A visit there will provide a great look at all our services, including the “Safety” tab that outlines our safety programs. All the Safety pages contain a feature you can use to communicate directly with our Director of Aviation Safety Programs. We look forward to your comments on the newsletter (or our other safety programs) and advancing Premium on Safety in step with your needs and suggestions. Fly smart and fly safe!