23 minute read

The Dream of the ’20s Is Alive in Portland: A Study into the Continued Proliferation of Historic Theaters in the Rose City - By Jeremy Ebersole

from UO ASHP 2019 Journal

by uoashp2019

The Dream of the ’20s Is Alive in Portland: A Study into the Continued Proliferation of Historic Theaters in the Rose City

Jeremy Ebersole

Advertisement

Portland’s Oriental Theatre opened on Grand Avenue on New Year’s Eve, 1927, to great acclaim. The latest of many grand movie palaces and smaller neighborhood theaters to open in the city, the Oriental’s fame was short-lived, and a succession of owners along with periods of darkness followed for the next 40 years. The city even took over operation for a short time in the mid-1960s when the Municipal (now Keller) Auditorium was being renovated, but even this could not stave off the wrecking ball, and in 1970 the magnificent theater was demolished for a surface parking lot that remains to this day. 1 Changing economies and competition fueled by television, suburban multiplexes, home video, and streaming, along with the more recent challenge of digital projector conversion, have spelled the end of the majority of historic theaters across the country. Despite the more typical fate of the Oriental, however, Portland, is fortunate to have retained a disproportionately high percentage of these old gems, and it is the purpose of this paper to speculate why. The pertinent questions are thus as follows: (1) Is Portland legitimately rife with historic theaters?; and (2) If so, what policies or other factors have contributed to their high survival rate? This study finds that Portland does have more operating historic theaters (OHTs) per capita than other cities and speculates that the cause may be a complex combination of preservation efforts, arts policies, and significant cultural forces.

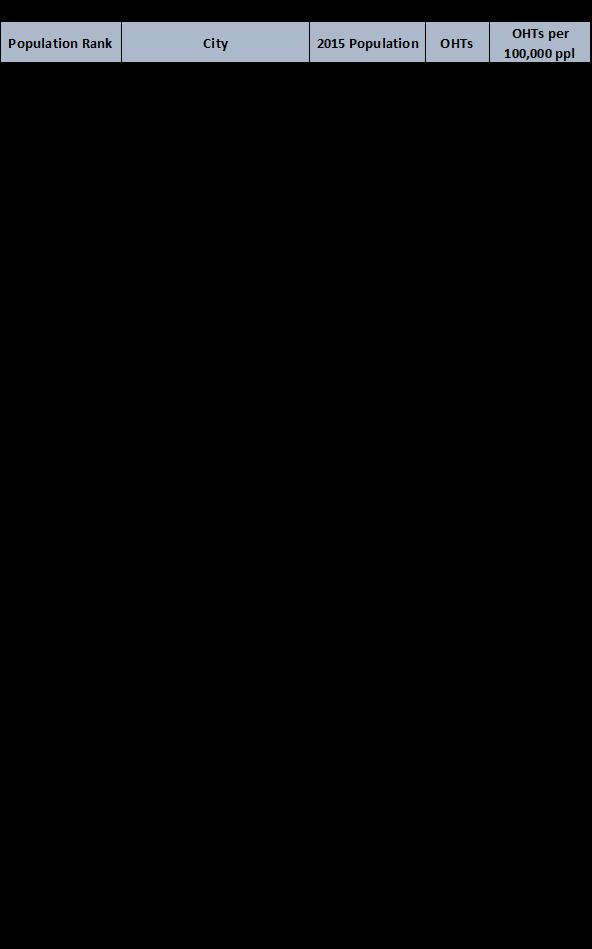

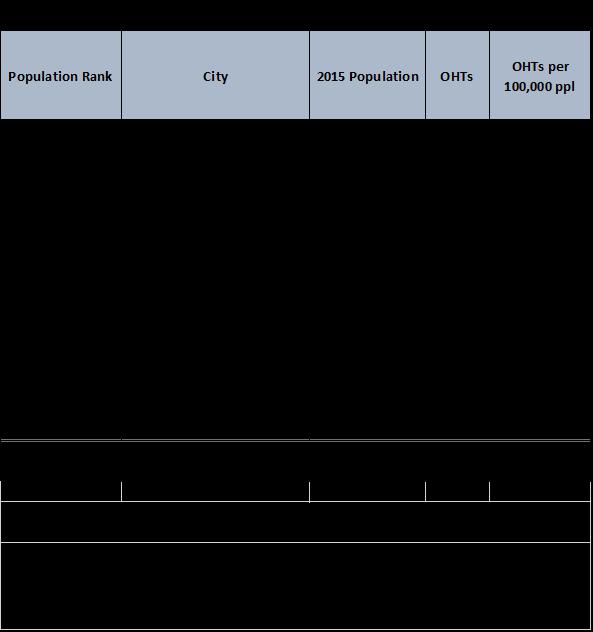

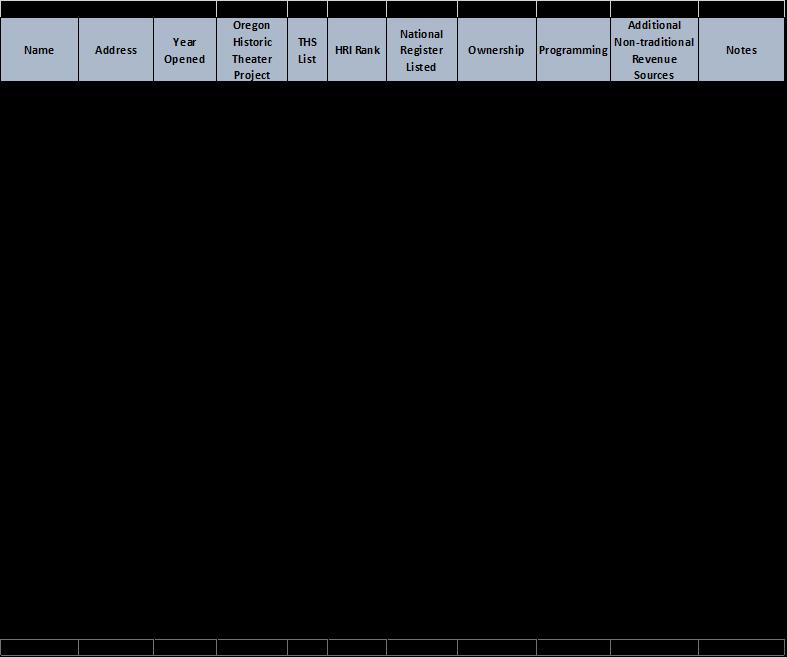

Attention is first turned to showing that the Rose City does indeed contain an unusually high number of OHTs. To do so, a thorough investigation was conducted comparing population data from the U.S. Census 2 for American cities with 2015 populations greater than 500,000 with national numbers of OHTs compiled in the same year by Curtis Cooper for the Theatre Historical Society of America (THS), a 40- year-old national non-profit organization dedicated to documenting the history and culture of theater buildings in the U.S. 3 To qualify for inclusion on the list, buildings must have been built prior to 1970 and had to be operating as a theater at the time. Cooper’s methodology in compiling the list was diverse and exhaustive, combing numerous websites, the THS archives, and real estate listings, among other sources (see Appendix A). The challenges of compiling an authoritative list of every operating historic theater in the country are myriad, however, not in the least because of differing definitions of what qualifies. Thus, while Cooper’s data was used as a baseline of comparison nationwide, the 2015 Oregon’s Historic Theater Project inventory (OHTP) compiled by the University of Oregon Community Service Center’s Community Planning Workshop (now called the Institute for Policy Research and Engagement) along

with Pacific Power, Oregon Main Streets, and Travel Oregon (now shepherded by Restore Oregon) was consulted as a backup for the city of Portland. 4 This survey had a cutoff year of 1965 (following the generally accepted 50 year rule) and did not include buildings originally built as something other than theaters. The variations in these methodologies produced slightly different results, with Cooper’s list containing six properties not on the OHTP list, which itself contained two unique properties (see Table 1).

ASHP Journal 201926 The results of the comparison are conclusive (see Table 2). Of the 34 U.S. cities with more than 500,000 people, Portland, though ranked twenty-sixth in population, 5 comes in fourth for number of OHTs (24) just behind Chicago (31), Los Angeles (42), and New York City (101), the largest cities in the country. Chicago’s population is four times that of Portland’s but it retains only 1.3 times as many OHTs. Los Angeles is six times larger than Portland and is the center of the film industry but has fewer than twice as many OHTs. New York City is a whopping 14 times more populous than Portland and arguably the entertainment capital of the world, and it still only has four times as many OHTs. Portland’s number is in fact twice as large as the average (which includes the weight of New York’s exceptionally high number). A fairer comparison, however, looks at OHTs per capita, and here Portland lands decisively at the top of the list, with almost four OHTs per 100,000 residents. Second place Detroit tops out with a ratio of 2.65:100,000, and the average is just a hair over 1:100,000. Thus, Portland has more than three times as many OHTs as the national average for large cities. Notably, even merging the Cooper and OHTP lists and using the strictest criteria possible of buildings built as theaters prior to 1965 and still operating as theaters in 2015, the results are still a good showing for Portland. Even with this handicap, Portland maintains 20 OHTs and a ratio of 3.17:100,000.

It is important to consider the limitations of these findings, however. Every effort was made to match the list of OHTs to their respective census tracts by examining which cities belonged to each tract and comparing them with addresses on Cooper’s list, but human error is a possibility. Also, this comparison looks at cities according to the U.S. census, not at metro areas. It is possible that expanding the search to include metro areas could yield different results. Similarly, in an effort to balance comprehensiveness with meaningful comparisons, this research does not include cities under 500,000. Finally, and perhaps most problematic but also most difficult to study, this study has not researched every historic theater ever built in the United States. It is possible than any number of factors led to more theaters having been built in Portland from the beginning, meaning the city may have just always been an attractive place for film exhibitors, rather than an ideal place for theater preservation. Gary Lacher and Steve Stone hint at this possibility in their book, Theatres of Portland, with the brief comment that “the city has actually had more theatre seats per capita than any other city in the country.” 6 What can be said with some certainty, however, is that the city of Portland does have more OHTs per capita than any

other large city in the country, and the next challenge is to determine why.

Research into this question was conducted by combing through old newspapers, scouring data from various arts organizations, comparing Oregon’s historic theater survey to that of Washington, web research, and conversations with various key stakeholders. A beginning look into the ways theaters have been saved around the country turns up a dizzying array of possibilities, where the most complex arrangements were often the most successful. 7 Two brief case studies of successful local OHTs turn up some promising clues, however. The Bagdad Theatre was built in 1927 to show first-run Universal films and followed a common line –turning to vaudeville in the 1940s and being triplexed (turning the existing single-screen venue into a three-screen venue) in 1973. A series of positive turns began when the theater hosted the 1975 Oregon premier of locally filmed “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” followed by its listing on the National Register in 1989. The turning point, however, was the 1991 purchase of the property by the McMenamins company, a local brewpub chain just getting off the ground and specializing in the restoration of historic buildings. Because of its additional revenue streams from other properties and sales of beer and food at the theater (a concept it had initiated in 1987 with the transformation of an old church into the Mission Theater), McMenamins could afford to operate the theater with $1 ticket sales. 8 The company enlivened the space by adding music, readings, classes, and documentaries to the repertoire and, according to the Los Angeles Times, served as “proof of the powers of

historic preservation, neon, and beer. In a city in love with making things and recycling them, it’s an old postcard with a fresh message scrawled on the back.… You can eat a meal and drink beer in the theater, a concept that’s novel in Los Angeles but old hat here.” 9 The Bagdad’s story displays a number of influences at work, namely the power of diversification, innovation, and culture in saving the building.

2019 ASHP Journal 27 Just a few miles north, the 1926 Hollywood Theatre has taken a different road. While it was also triplexed and added to the National Register, the Hollywood’s savior was not a company but a partnership among the government, a non-profit, and countless individual volunteers. The Oregon Film & Video Association (later Film Action Oregon) was formed as a non-profit organization by the state government to support local filmmakers but decided in 1997 to purchase the theater and fix it up to show second run, classic, children’s, and independent films, along with hosting special events. 10 With the help of many volunteers and donated supplies, the theater has grown in prominence and is supported by not only by the usual ticket and concession sales but also by the memberships, donations, grants, arts tax money, and tax-free status that being a non-profit provides. While the Hollywood’s status as a non-profit makes it very different from most Portland OHTs, its focus on eclectic offerings is common. Particularly important is the fact that threequarters of Portland’s OHTs, like the Hollywood, do not rely primarily on first run films for their repertoire, meaning a higher cut of the box office stays in house. 11 While these two stories are just a sampling, they

demonstrate an important fact: Portland’s OHTs do not appear to be primarily the result of policy initiatives.

ASHP Journal 201928 Oregon’s state support for the arts has been historically mediocre, though not without influence, and what does exist is only accessible to non-profits. 12 The State Arts Action Network ranked Oregon twenty-sixth in the U.S. for overall state allocation to the arts in 2017, 13 and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies puts the state in the fourth of five tiers for per capita arts spending. 14 More specifically, unlike states such as Iowa and New Mexico, no statewide initiative focused on historic theaters has been adopted in Oregon, despite the recent OHTP survey. Furthermore, while Washington’s earlier historic theater survey lists multiple state-level initiatives focused on supporting historic theaters that invested an average of $1 million per year between 1991 and 2008, 15 Oregon’s survey is mute on the point, seeming to indicate that no such initiatives have taken place here. 16 This should come as little surprise, however, given Oregon’s reputation as a “fairly anti-tax state in which new taxes and fees are adopted with reluctance.” 17 In fact, a recent study finds Oregonians have “little enthusiasm for government action to improve the economy.” 18 Another feasible policy solution –preservation policy –fares better, with 70% of Portland’s OHTs carrying some kind of designation, ranging from listing on the 1984 Historic Resources Inventory to individual listing on the National Register. Nonetheless, it is insufficient to say these minor protections, which are helpful but insufficient factors, are solely responsible for Portland’s OHT abundance. The rest of the answer likely lies in cultural factors, beginning with the redemption of arts funding.

Government funding for the arts has improved in recent years at both the city and state levels, and while the relatively recent implementation of these policies and their limitation to non-profit organizations make them an unlikely silver bullet for preserving historic theaters, the unique nature of these funding mechanisms may help create a strong culture of support for entertainment of all types in Portland. To remedy the historically lacking public support for the arts and heritage in Oregon, “A formal cultural planning task force –including the arts, humanities, community development, heritage, historic preservation and tourism –was created by passage of a special bill in 1999.” 19 The result of this task force, the Oregon Cultural Trust, was created “[t]o increase public and private investment in culture, to protect and stabilize Oregon's cultural resources, to expand public access to and use of Oregon’s cultural resources and enhance the quality of those resources, [and] to ensure that Oregon’s cultural resources are contributors to Oregon’s communities and quality of life.” 20 Involving citizens in the planning process naturally spurred increased awareness of the important role the arts play in enhancing quality of life and community identity. Two primary ways citizens interact with the Trust are by purchasing special license plates, which are seen throughout the state, and through the Cultural Trust Tax Credit, which “allows taxpayers who contribute to qualified nonprofits to redirect some of their tax payment from the General Fund to the OR Cultural Trust.” 21 The success of this mechanism is impressive; 22

additionally, “the very existence of the Trust also works to support the cultural ecology of the state of Oregon.” 23 In a similar way, Portland voters’ 2012 ballot measure approval of a $35 per person annual arts tax forces citizens to at least confront the idea of culture by mandating that the tax paperwork is filed by everyone, even if the citizen is exempt from paying. 24 These recent policies both reflect and influence a growing cultural awareness of the arts that bleeds into theater support of all kinds. 25 They are not, however, the only cultural drivers at work.

Among the most important of these cultural instigators is certainly McMenamins. The company’s late 1980s introduction of the cinema-pub concept, even if it used a former church as a venue, set off a trend that today supports 40% of Portland’s OHTs. “Portland led the way for the film community by establishing a new form of entertainment: the brew-pub theatre, restored out of older historic buildings.” 26 The city’s historic love of beer goes hand in hand with this success, as “Oregon and Washington are the two leading states in their proportion of draft beer consumption –27 percent of the beer sold there is drawn from taps, compared with just three percent in neighboring California.” 27 McMenamins’ success also highlights another reason for the success of local historic theaters: adaptability and innovation. Larcher and Stone speculate that “by the early 1970s, many small neighborhood and downtown theatres became distinctive in showing adult films, and it is only with this dubious credit that they survived at all.” 28 Many of today’s OHTs showed second run films in the 1990s, 29 and varied programming remains a strength of the majority. Similarly, more than half have taken a page from McMenamins’ book and diversified their offerings –from live music to arcade games to a video store.

2019 ASHP Journal 29 The people of Portland are also especially strong supporters of film, with the city earning the recent distinction of America’s best city for movie lovers. 30 This, combined with Portland citizens’ (if not always their government’s) love of the arts has helped ensure the success of many old cinemas. As evidence of the population’s support of cinema and the arts, a recent study found that Oregon’s share of arts and culture production is 9.3% greater than the national average. 31 The state also has the thirteenth highest percentage of workers in cultural occupations in the nation, with Portland landing in the top 10% nationwide. 32 Specifically addressing movies, another 2018 study finds that 56.3% of Multnomah County residents attended movies in the last three months, a number that places it in the top 15% of surveyed counties nationwide. 33 Finally, Portland’s neighborhood system and the culture it engenders is also healthy for OHTs. The implementation of the system in 1974 lends itself to support of community establishments. “Fueled in part by ‘buy local’ supporters who favor neighborhood establishments over national chains,” says the OHTP, “many venerable theaters are experiencing a comeback.” 34 Larcher and Stone are also bullish on the effect of neighborhoods, claiming, “the strength of these examples [of OHTs] has been the neighborhoods of Portland. With the refurbished growth of the inner communities, new populations and families have given Portland a continuing chance for theatres to

not only survive, but to entertain its citizens in the same manner as on those rainy nights of 80 years ago.” 35

Thus, while Portland’s preponderance of OHTs is apparent, its causes are more difficult to pin down. Despite limited direct support from policy initiatives, Portland’s historic theaters may indeed be benefitting from the larger cultural atmosphere the city and state’s unique arts funding structures engender. Much of the success of these theaters seems to be due to cultural factors including the influence of one substantial preservation-based brew-pub company, prudent adaptability in programming, a strong overall movie culture, and the city’s unique neighborhood system. The topic remains ripe for further research, including looking into whether a lack of development pressure in the city during the 1960s to 1990s (when most historic theaters nationwide were lost) played a meaningful role in the survival of Portland’s old theater buildings. Additionally, further examining the historic theater-specific policy initiatives in states that have implemented them may yield further tools for improving the still precarious position of many of Portland’s OHTs. For the time being, Portlanders can enjoy their documentaries, live music, arcade games, and even some first run films in the city’s many historic theaters, relishing the fact that they are blessed with an unusual abundance of them

Endnotes:

1 Charlie Hanna, “Helped by City Lease, Oriental Theatre ‘Fabulous’ Again,” Portland Sunday Oregonian, October 3, 1965, 6F; Bryan

Krefft, “Oriental Theatre,” Cinema Treasures website, accessed October 29, 2018, http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/2728.

2 “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2017 Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017,” U.S. Census Bureau, May 2018, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/ jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

3 This data was provided by Patrick Seymour, THSA Archives Director, in an email dated October 31, 2018. A November 6, 2018, email conversation with Mr. Cooper also revealed that the information has since been made available online at www.bestremainingseats.com.

4 Community Planning Workshop, “Oregon Historic Theaters: Statewide Survey and Needs Assessment” (Eugene: University of Oregon, 2015), https://orhistorictheaters.files.wordpress.com/20 15/09/oregon-historic-theaters-needsassessment1.pdf.

5 Just below Memphis and above Oklahoma City.

6 Gary Lacher and Steve Stone, Theatres of Portland (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2009), 7. A list compiled by Richard C. Prather in 2001 and provided by THSA in an email dated November 1, 2018, lists 375 theaters having existed at one time or another in the Portland metro region. Many of these were built after the 1960s, but many of them were not. For as many historic theaters as have been saved in Portland, many more have been lost.

7 League of Historic American Theatres, “Historic Theatre Rescue, Restoration, Rehabilitation and Adaptive Reuse Manual” (Forest Hills, MD: League of Historic American Theatres, 2012), https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/

LHAT/787daa61-5466-41d5-ad6f28c34e98e17d/UploadedImages/Site%20Docs/L HAT%20Rescue%20Rehab%20Manual.pdf.

8 John Pastier, “The Brews Brothers,” Preservation Magazine, Nov/Dec 1996, 70–73.

9 Christopher Reynolds, “Serving Up Beer, Films,” Los Angeles Times, August 25, 2013, L4.

10 Raymond F. Quinton, “Hollywood in Portlandia,” Historic Property Magazine, December 1998, 12, 14.

11 This detail about box office percentages kept in house for first run films versus other offerings was garnered through a phone conversation with Doug Whyte, executive director of the Hollywood Theatre, November 5, 2018.

12 “Investing in Oregon’s Arts,” Oregon Arts Commission website, accessed October 29, 2018, www.oregonartscommission.org/grants.

13 “Facts and Figures,” Americans for the Arts website, accessed October 29, 2018, www.americansforthearts.org/byprogram/networks-and-councils/state-artsaction-network/facts-figures.

14 “Per Capita Legislative Appropriations to State Arts Agencies,” National Assembly of State Arts Agencies website, accessed October 29, 2018, https://nasaaarts.org/nasaa_research/per-capita-legislativeappropriations-state-arts-agencies-2.

15 Artifacts Consulting, “Historic Theatres: Statewide Survey and Physical Needs Assessment” (Olympia: Washington State Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation, 2008), https://dahp.wa.gov/sites/default/files/theater%2 0survey.pdf.

16 This may be changing, but not as a result of state policy. Restore Oregon, the state preservation non-profit, has carried the torch begun with the OHTP forward and, as “part of a years-long initiative to identify and bring resources to Oregon’s historic theater owners and operators,” brought the League of Historic American Theatres regional conference to Portland this year. Though the organization was initially reluctant due to poor attendance at previous conferences in the Pacific Northwest, the effort, started by a local theater owner, was ultimately a sellout. Restore Oregon did large amounts of publicity and reached out to theaters previously on the organization’s endangered places list to encourage attendance. Additionally, they facilitated scholarships from Travel Oregon for 21 attendees. The conference was so successful, Portland is now in the running to host the national conference in the future. This information comes from a conversation with Katelyn Weber, Preservation Programs manager at Restore Oregon, October 26, 2018. (Upon my mentioning the subject of this paper, Katelyn quipped that Portland is “lousy with historic theaters.”) See also “Recap: League of Historic American Theatres (LHAT) 2018 Fall Regional Conference,” September 14, 2018, Restore Oregon website, https://restoreoregon.org/2018/09/14/recapleague-of-historic-american-theatres-lhat-2018- fall-regional-conference.

17 Kelly J. Barsdate, “Cultural Policy Innovation: A Review of the Arts at the State Level” (Washington, DC: National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, 2001), www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/ arts-bgrd.pdf, 4.

18 “Top Findings from the 2013 Oregon Values and Beliefs Survey,” Oregon Values and Beliefs Project, http://oregonvaluesproject.org/findings/topfindings.

19 Barsdate, “Cultural Policy Innovation,” 2.

20 Ibid.

21 Arts, Culture, and Oregon’s Economy (Eugene: ECONorthwest, 2012), https://issuu.com/oregonculture/docs/cultural_tr ust_economic_impact_stud.

22 $3.9 million was donated in this manner in 2011, some of which is distributed to the State Historic Preservation Office; ibid., 18.

23 Joshua Cummins, Milton Fernandez, Jennie Flinspach, Rogers, J. K. et al., The Impact of the Oregon Cultural Trust on the Statewide Cultural Policy Institutional Infrastructure (Eugene: University of Oregon Center for Community Arts and Cultural Policy, 2018), 21, https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstrea m/handle/1794/23299/The%20Impact%20of%2 0the%20Oregon%20Cultural%20Trust.pdf?sequ ence=1.

24 “Arts Tax,” City of Portland website, accessed October 29, 2018, www.portlandoregon.gov/revenue/60076.

25 There is evidence of support for the arts in Portland prior to these policies as well. A 1984 Oregonian poll found the nightlife and entertainment scene were among the city’s most attractive elements. This information comes from a document in the THSA archives, “The Business of Show Business: Economics and the Performing Arts Center,” produced by the Performing Arts Center likely as part of a fundraising campaign in the late 1980s.

26 Larcher and Stone, Theatres of Portland, 8.

27 Pastier, “The Brews Brothers.”

28 Larcher and Stone, Theatres of Portland, 7.

29 Pat Holmes, “Staying Afloat as a SingleScreen Theater,” This Week, November 9, 1994, 24.

30 As awarded by real estate blog Movoto based on movie theaters per capita, video rental stores per capita, number of indie theaters per capita, number of annual film festivals, number of film and cinema museums, number of film societies per capita, number of drive-in theaters per capita, and bonus points for specialty theaters per capita. Natalie Grigson, “The 10 Best Cities for Movie Lovers,” Movoto blog, October 9, 2013, https://www.movoto.com/blog/topten/movie-lovers.

31 Cummins et al., The Impact of the Oregon Cultural Trust on the Statewide Cultural Policy Institutional Infrastructure, 83.

32 Arts, Culture, and Oregon’s Economy, 2.

33 The same study finds that this top 15% finish for film attendance is better than the (still strong) top 20% finish for attendance at live performing arts or popular entertainment events. In addition, all three percentages climbed more than 5% from 2011 to 2014. Roland J. Kushner and Randy Cohen, Local Arts Index (LAI), United States, 2009–2015 (Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2018) https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36984.v1.

34 Evidence from the 2013 Oregon Values and Beliefs Survey also points to an anti-materialist bent, which could lend itself to more resources being spent on experiences such as films: “Given a choice between statement A (Our country would be better off if we all consumed less) or B (We need to buy things to support a strong economy), 57% of Oregonians favor consuming less (29% strongly), with 35% preferring to buy things (14% strongly).”

35 Larcher and Stone, Theatres of Portland, 99.

Appendix A

Cooper explained his methodology in an email dated November 7, 2018: “The information came mostly from these sources, but also there are times where a stray newspaper or magazine article leads me down a path as well: ● I started with the Cinema

Treasures ‘open’ list for each state. It was a huge job sorting out what was open and what fit my criteria (pre-1970) because they don’t designate entries as historic at all. ● I then started thinking about

Cinema Treasures “closed” list for each state, too. This was a bigger and longer nightmare because there are tons of theaters listed as closed that are actually demolished, or maybe never existed (yes, you read that right –people often post theaters that they “think” or “heard” were there for two years in 1918–1920). ● ATOS’s theater organ list ● LHAT has member and nonmember lists, with not-so-great information ● Water Winter Wonderland for

Michigan ● Kansas Historic Theatre

Association’s member list ● Preservation Directory –not the most reliable ● Old THSA conclave lists

● Roadside Attractions site ● Cinema Tour site ● “Los Angeles Theatres” (formerly Historic Los Angeles Theatres Google page) –a wonderful resource for SoCal ● TexasEscapes.com theater section ● Google Alerts –daily email for

Historic Theaters, Movie Palaces, etc. ● Facebook Google Maps was invaluable for determining if something was still there and/or had the correct address. I found that many small town theaters for some reason don’t have a [web]page or Facebook page of any kind, so I learned how to check for local business[es] that co-advertise for them as well as city hall listings (and city council meeting minutes) to see if a place was open. Commercial real estate listings were also often helpful in finding theaters and their status. Regarding criteria, I have struggled with that all along. The year 1970 seemed like a good cutoff point because by that time theater owners had stopped caring about what a theater looked like and built things that in later years nobody would miss if it disappeared. Even a good deal of the 1960s wasn’t so great, but they at least tried to create interesting facades and lobbies. However, when it comes to types of venues, I have adjusted my criteria multiple times as I have learned more. As that has happened, I occasionally will run into something in my database and debate (at too much length) if it still really belongs there. I include: ● Movie theaters

Legitimate theaters Former theaters that have been turned into other things, but still have enough elements that would allow them to become theaters/performance venues again. This often encompasses churches, retail and health clubs. School auditoriums that now are full-fledged performance spaces or have always had dual roles in the community as both a part of the school and a community gathering space. Churches and other historic buildings converted prior to 1970. Old ballrooms and civic auditoriums, which have stages and have presented many shows (and sometimes have/had massive organs) ● Historic theater buildings that have been substantially rebuilt inside (I have one where the theater was mostly gone, but two childhood friends got together and rebuilt it using all pieces of other historic buildings) ● Theaters that have been multiplexed Occasionally I will decline to put a theater on the list because it is [in] such bad shape because of neglect or because of owner modifications, but not often. I mostly don’t remove venues unless they have been demolished or burned down, or they’ve been turned into a brewery or some other interiorclearing business.”