11 minute read

Above the Mists of Africa

by Debra Bouwer

the Mists of Africa

Advertisement

— Mt Kenya —

Wet and sweaty after five days on the mountain, we crammed into a beaten-up, blue, 1952 Land Rover. Within seconds the windows had misted up. The driver wired the doors shut and off we went.

Lake Michaelson on Mt Kenya: Dmitry Yurlagin

Two days of heavy rain and a stream of traffic had turned the steep, downhill Chogoria road into a pavlova of whipped-up mud and deep trenches.The vehicle looked as bad as the road. Door handles were missing, the front bumper buckled and bent, and one wiper blade was all that remained. The roof hadn’t escaped unscathed either; its dented demeanour was evidence that at some point it had sustained a roll.

Gripping the steering wheel, our driver aimed the Land Rover down the ruts, at times steering up against the bank, using it to keep the vehicle “on the road”. Two hours later our downhill mud-ski ended and we emerged from the camphor forest. The rain stopped. The road ahead was dry. Behind us the mountain hid under a blanket of cloud.

Our trek up Mt Kenya had begun five days earlier on a sunny morning. Mt Kenya, like its southern sister, Kilimanjaro, is a volcano formed about three million years ago. Although Mt Kenya ranks as Africa’s second-highest peak, it once took centre stage, reaching an estimated height of over 6,000m. All that remains today are some glaciers and jagged eroded peaks. Home to the mountain god of the Ngai people, it boasts three summits named after Maasai chiefs; Nelion, Batian (both technical climbing peaks) and Lenana.

Lenana, like Kilimanjaro, is a trekking peak where a pair of hiking boots, fitness and determination are all that is required to reach the summit.

Mt Kenya is beautiful. Her many-sided approach means she presents a range of different faces, each with unique flora and fauna. She rises above the surrounding plains like a series of arthritic spines, casting endless shadows over the valleys below.

Having chosen a six-day trek along the Sirimon Chogoria route, our first day was a dusty fourhour walk to Old Moses Hut. Approaching camp, we were greeted by the happy clatter of pots and pans as teams already in situ went about preparing their evening meal. Porters darted to and fro, men huddled over gas burners and a cacophony of radio songs echoed across the courtyard. Outside the huts, trekkers huddled together in tiny patches of fading sunlight.

Early morning our door creaked open and the light crept in, beckoning us to venture onto the mountain. It was a clear day. Far in the distance, Nelion and Bation peered over a ridge to inspect the morning traffic in the foothills.

The vegetation on Mt Kenya is diverse. At first we found ourselves in a heath zone with gnarled sedges and red hot pokers. Prickly tussock grasses bit through our socks. A never-ending stream of fat safari ants crisscrossed the path, oblivious to the increasing gain in altitude. Alpine chats and starlings followed us, darting back and forth,

Kilimanjaro’s Night Sky: YongKX

WB YEATS, The land of heart’s desire

catching their afternoon meal as it sprung from the grass. Out of nowhere, a wide-eyed duiker bolted across the path. Our stop for the night was at Liki North, a remote and seldom used camp. A lone wooden hut resides in the haunted narrow valley alongside a frozen stream; its decaying timber like pages of an unpublished novel. The silence was almost deafening until late afternoon when shrill cries of a thousand ghosts screamed through the valley. “Hyrax,” yelled Patrick, our guide, “hyrax!” The rock hyrax is a short, squat, thickset and rotund creature. With their stubby legs and soft-padded feet, they dart about the rocks calling across the valley. Night comes quickly on the mountain, and with it, the biting cold.

Like every morning, the next day we were met by the warmth of the rising sun and slowly headed up and away from our valley of solitude, to join the trail to McKinders Hut. As though turning the page of a picture book, we found ourselves dwarfed by massive, green-leafed scenecios with their craggy trunks. The path disappeared into the shadow of their leaves and the entire valley seemed awash with green groundsel. Dotted along the ridge were inflorescent finger-like tendrils of lobelia telekii reaching for the sky. It was like walking through a scene from MiddleEarth meets Day of the Triffids.

The path to McKinders snakes through the valley, then rises steeply up a stony ridge to the camp. We were welcomed by a colony of hyrax, grunting and chattering welcome messages. Above us loomed the chieftains of Nelion and Batian and, hidden over a ridge, Lenana waited patiently to greet us.

The next morning saw an early start – 4am! We picked our way through steep, rocky, stone scree guided by the light of our headlamps. With Patrick at the helm, we made our way through the mist and away from camp and, in the early morning sunlight, we basked at the summit of patient Lenana.

The approach route was beautiful, yet nothing prepared us for the exquisite tapestry laid out on the descent. Here Mt Kenya presented us with her most captivating face; steep, smooth-sided cliffs, the incredible avocado green Gorges valley, and the azure blue and turquoise Lake Michaelson. The best surprise was her cloak of endless groves of yellow and orange protea bushes. That night we camped in Alice’s Wonderland.

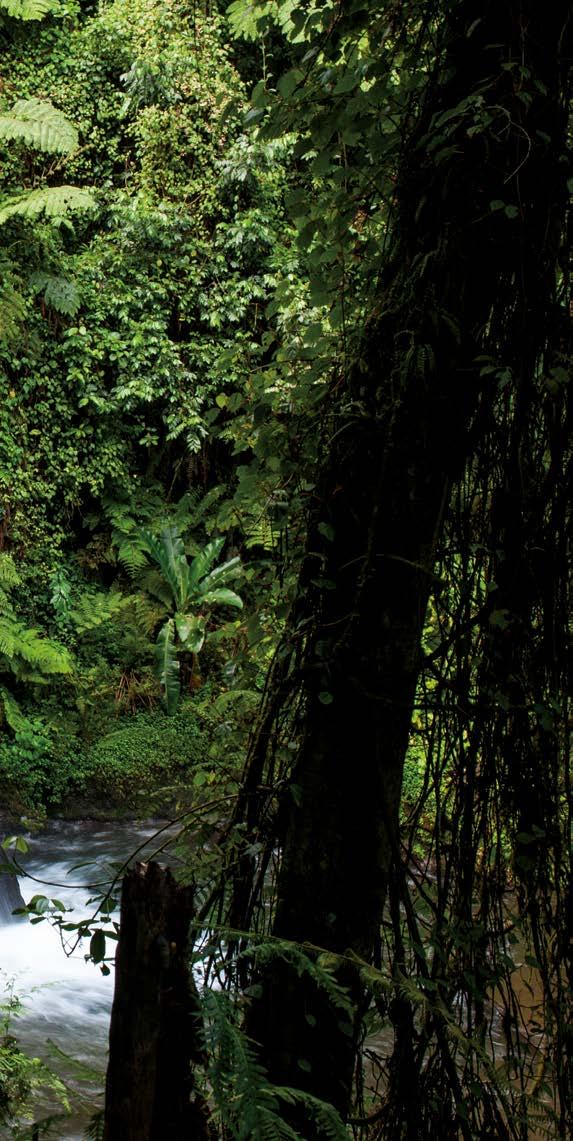

So it was that we reached the final day of our descent. The night had brought intermittent rain, and left a mist to accompany us past steep buttresses to the base of the mountain. We found ourselves in a rosewood forest, with long, twisted lichen braids hanging like curtains at the end of a mesmerising show. All that remained was a forest of camphor and a long muddy road to the Chogoria Village.

— Mt Kilimanjaro —

350km to the south, lies the snow-capped Kilimanjaro, reaching 5,895m. “Kilema Kyaro”, as she is known in the Chagga dialect, means “’‘impossible journey”, while “njaro” means “demon of the cold”. So great is her global attraction that each year about 24,000 people gather in the hopes of reaching her summit.

Mt Kilimanjaro route to the summit: Peter de Jong

Trekking through the forest on our first day was like walking in a fairyland. Heavy rain the night before, coupled with the morning heat, had spread a blanket of mist which hung suspended above the thick mud that gathered under our boots. Tall trees fought for a patch of sun, their feet firmly anchored by a maze of roots. Lichens hung in sheets from branches and tiny red flowers decorated the forest floor. All the while, a stream of heavily laden porters trudged past us on their way to Machame Camp, watched by the shy black-andwhite colobus monkeys.

Our first cold night on the mountain passed quickly and we woke to the familiar sound of pots clattering and porters singing. The smell of cooking eggs and porridge, mixed with the dankness of the forest, drove us from our tent to an incredible sight. Shrouded in cloud the evening before, the summit of Kilimanjaro now stood proud, her glacial mantle set afire by the morning sun.

Kilimanjaro comprises three volcanoes, Shira and Mawenzi, which are extinct, and Kibo, which is dormant. It is Kibo that forms the summit peak, her last eruption being about 100,000 years ago, resulting in the loss of five metres from her summit.

That day our aim was Shira Camp, a long, steady climb over rocky terrain, amid everlasting flower bushes resembling overgrown pom-poms. At about 12pm each day, the mist rolls in, filling the valley below and, for every 200m climbed, the temperature drops around two degrees. Along the paths grow grey shrubs and the once tall aquaria trees, now short and squat and struggling to survive in hostile conditions.

Shira is a dusty, sprawling camp, which erupts into a hive of activity each day as hundreds of tents are spread out in preparation for the afternoon show. Over the course of the day, the sun and the clouds compete for attention. As the afternoon draws to a close, the sun steals the final show by painting the skies bright orange and red before taking up its evening rest. Being equatorial, sunrise and sunset on these mountains is abrupt and night temperatures plummet. It is not surprising to wake to a camp covered in a thin veil of ice.

Heading away from camp, we stopped and looked back. We had literally stepped out of one geographical zone into the next. Unlike Mt Kenya’s complexity of vegetative zones, Kilimanjaro is neatly laid out as though its creator walked about with a measuring tape, demarking zones of 1,000m each. The base is a thick rain forest, then a heath zone, misty and rocky. Above that lies a lunar landscape of contorted volcanic rock and then a zone of snow and ice. Walking among the endless streams of molten lava rock, I became acutely aware that we were walking on a volcano. Millions of years of rock and debris lay around us, gnarled and crumpled by the sheer heat of the volcanic forces that blew it from its prior resting place.

A happy trekker above the clouds: mountaintreks

“Mountains are earth’s undecaying monuments.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Continuing along the Machame route, one of seven routes to the summit, we headed past “Lava Tower” to Baranco Camp. Here, towering scenecios stand as beacons of survival. These incredible plants have adapted to high-altitude living. Each day their leaves open, forming a rosette, capturing moisture from the air. At night they wrap themselves up, letting gravity take the moisture to their hollow core. As the leaves die, they wrap down around the trunk, insulating it against the cold.

A short scramble took us up the imposing Baranco Wall and into endless valleys. Our companions for the day were large black crows. Joining them was the odd chat and grey field mice scurrying about in the undergrowth.

Soon, Barafu Hut came into view, our last night’s stop before summit. Barafu means “ice” in Swahili and, true to its name, it is a cold and inhospitable camp. Tents squashed onto bits of open ground, their pegs buckled against the hard earth. Porters huddled against rocks, seeking shelter. Trekkers’ boots lay discarded in the dust. The howling wind whipped through camp, stealing much-needed oxygen.

After a short sleep, our guide Juma, assisted by the rising moon, pulled us from our warm beds. Heading up to the famous Uhuru peak, I recalled how at the start of the journey I had taken two steps each second. Now every two seconds, I was taking one step. Time was reversed as we slowly moved forward. Up here I felt like nothing more than an inconspicuous stitch on earth’s infinite tapestry.

The air is thin and biting; the moonlit landscape stark. Nothing moves except the biting wind and melting ice. All you hear is your breathing and feet crunching through frozen scree. I once heard that if you make it to sunrise, you will make it to summit. The thought of a warm bed, a hot cup of tea, a descent to lower altitudes are an easy lure to a tired mind and ailing muscles. There is something magical about a rising sun on a bitter morning. It lifts your spirits and bathes everything around you in a wash of golden light. Unlike Mt Kenya, summit pull is a good two hours longer and the scenery on the upper ridges more inhospitable. To the far right the volcanic vent of Kilimanjaro lies dormant along with massive towering blocks of the remains of Furtwangler Glacier. Ahead, stands the rickety remains of the summit board.

Just three degrees south of the equator, Mt Kenya and Kilimanjaro stand as beacons in Africa. Their unsung heroes are the many guides and porters who work tirelessly to showcase their beauty to endless visitors.

Africa is more than endless savannas with teeming wildlife. She is more than vast stretches of ocean and craggy shorelines or the canyons of Augrabies Falls or Blyde River. Above the clouds lie incredible mountain peaks, with such a diversity of plant and animal life, that it feels like a world unto itself. Perhaps they are indeed the mystical lands which grew from Jack’s beans, all those years ago.