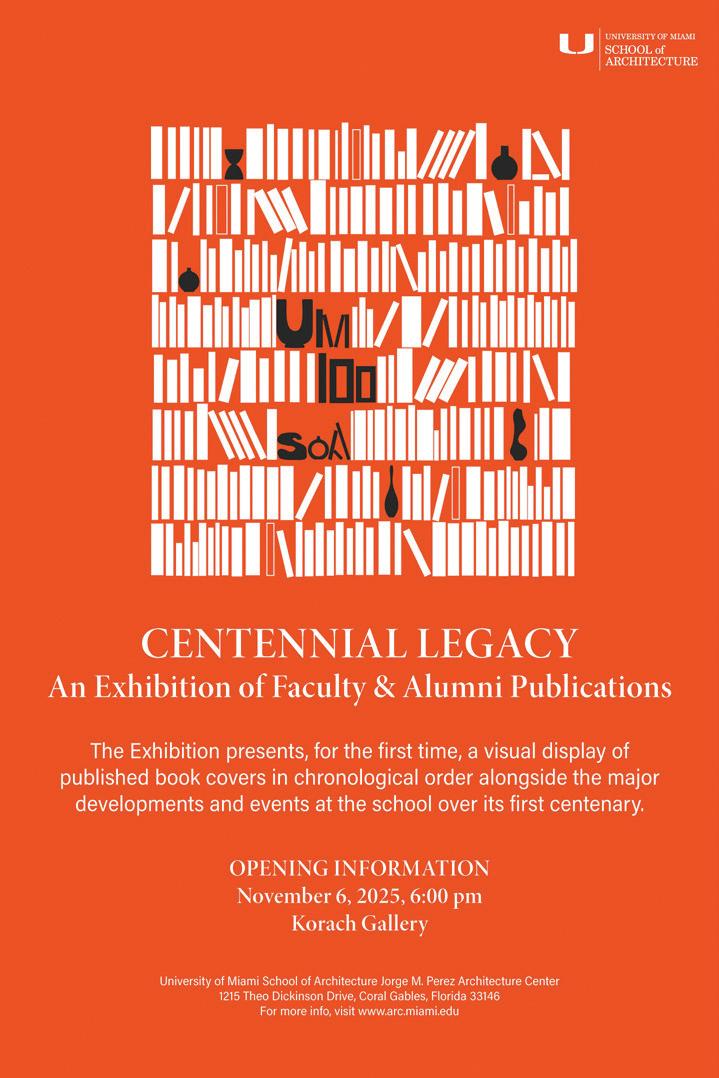

CENTENNIAL LEGACY

An Exhibition of Faculty and Alumni Publications

University of Miami School of Architecture

Fall 2025 - Spring 2026

University of Miami School of Architecture

Fall 2025 - Spring 2026

University of Miami School of Architecture

Fall 2025 - Spring 2026

Dedicated to the memory of Professor Teofilo Victoria, (1953-2024)

Figure 1 Centennial Legacy Exhibition Poster, © Varsha Gopal

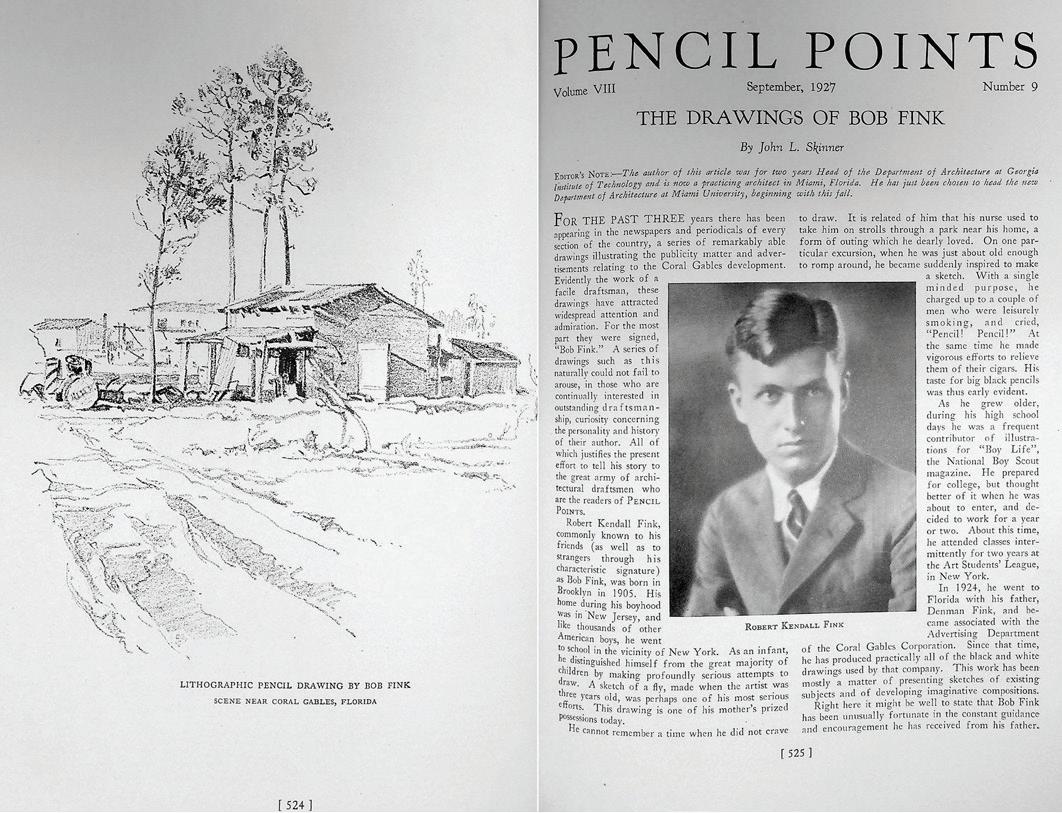

Figure 2 John Llewellyn Skinner, “The Drawings of Bob Fink,” Pencil Points VIII, no. 9 (1927)

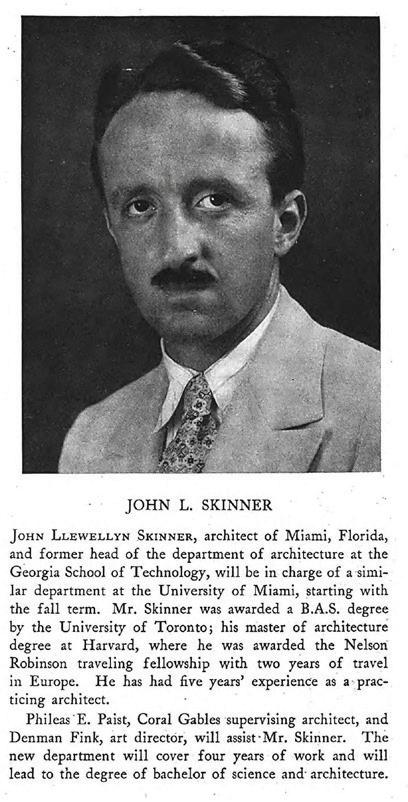

Figure 3 John Llewellyn Skinner, “Whittlings,” Pencil Points VIII, no. 1 (1927)

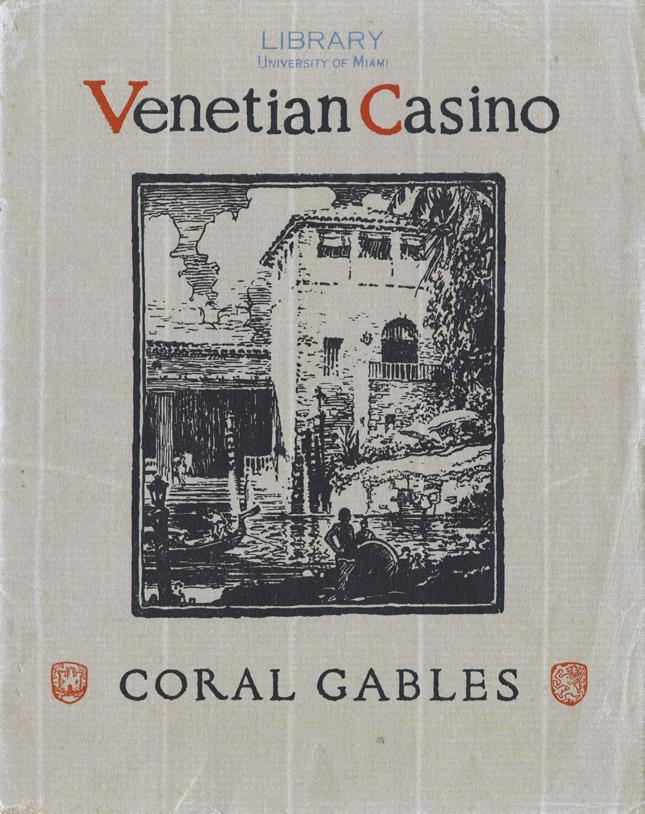

Figure 4 George E. Merrick, Venetian Casino: Coral Gables (1924), cover by Denman Fink

Figure 5 Robert Fitch Smith, The Work of Robert Fitch Smith, A.I.A. (1941), cover

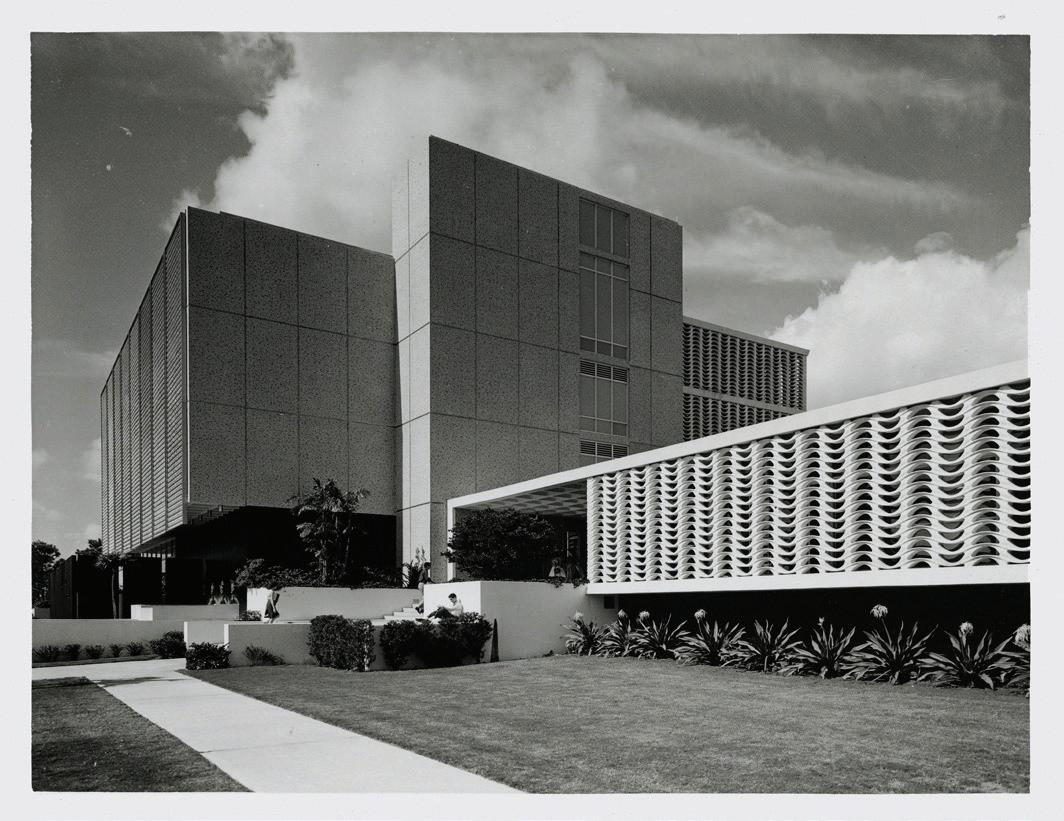

Figure 6 Exterior view of the McArthur Engineering Building, University of Miami Historical Photograph Collection, University of Miami Library, Coral Gables FL

Figure 7 University of Miami School of Architecture, Marion Manley Buildings, photo © Steven Brooke

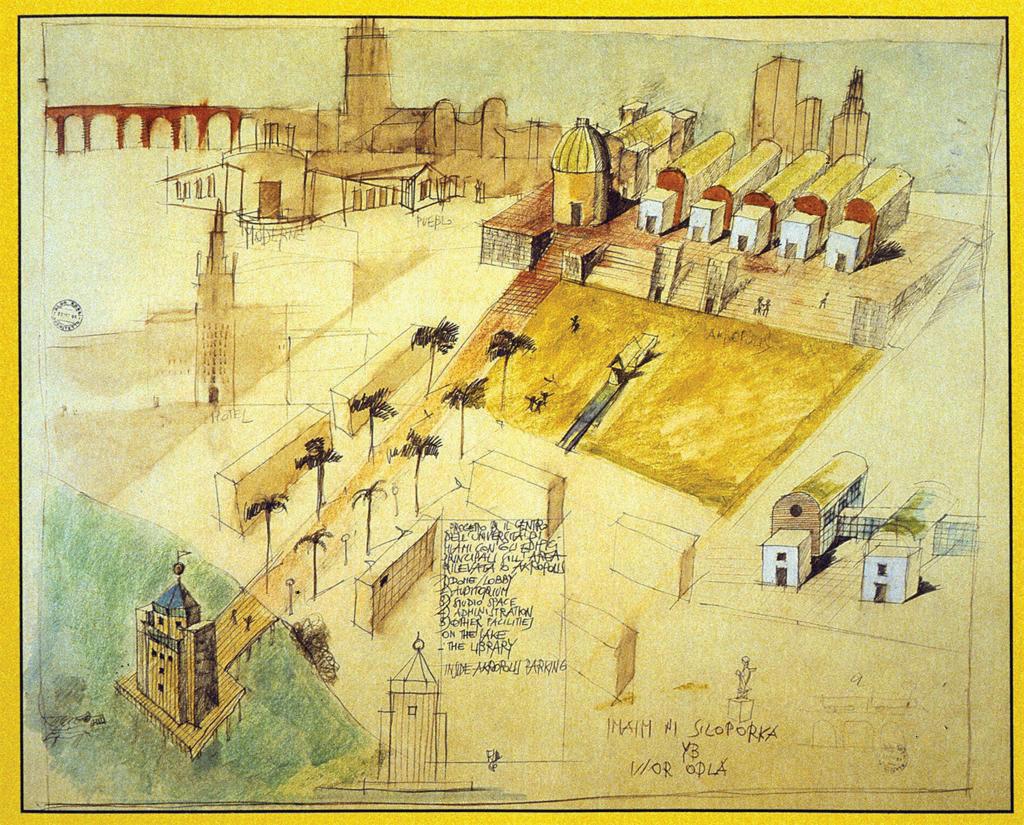

Figure 8 Aldo Rossi, Proposal for a New School of Architecture at the University of Miami (1986), University of Miami Architecture Research Center

Figure 9 Jean-François Lejuene, ed., The New City (1991), cover

Figure 10 University of Miami School of Architecture, Jorge M. Perez Architecture Center, Léon Krier and Merril, Pastor & Colgan Architects, photo © Steven Brooke

Figure 11 University of Miami School of Architecture, B.E. & W.R. Miller BuildLab, Rocco Ceo et al., photo © Steven Brooke.

Figure 12 University of Miami School of Architecture, Murphy Design Studio, Arquitectonica, photo © Miami in Focus

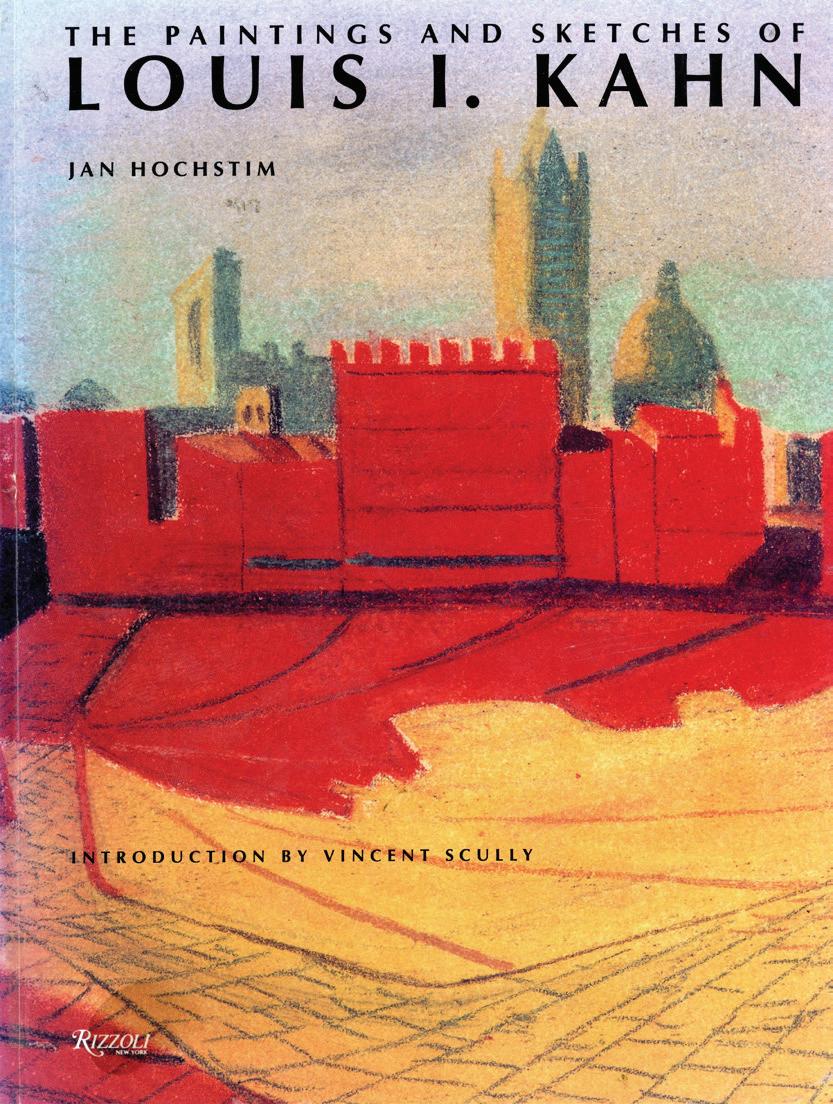

Plate 1 Jan Hochstim, The Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn (Rizzoli, 1991), cover

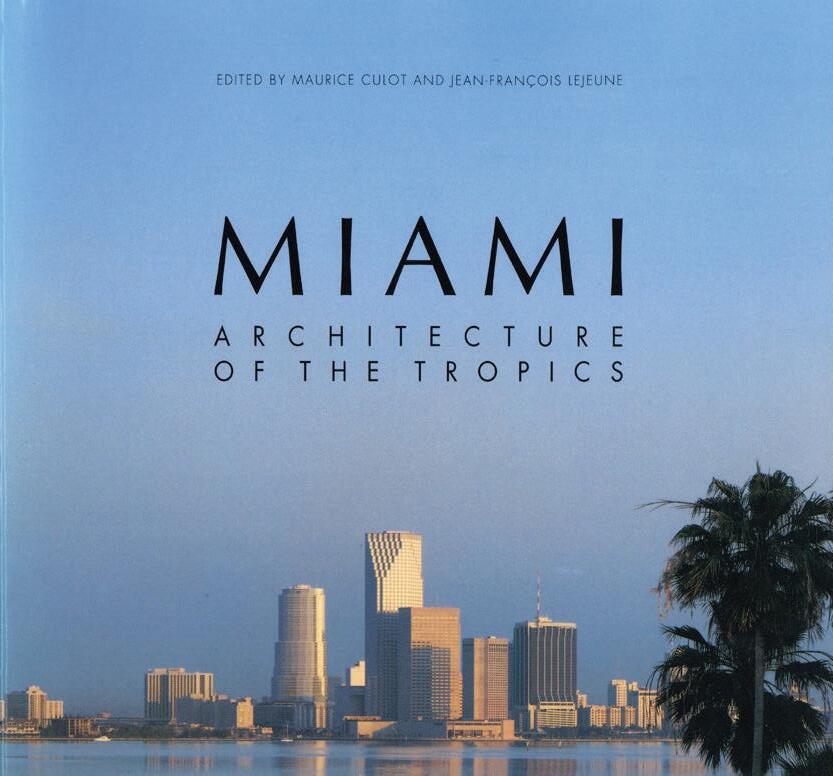

Plate 2 Maurice Culot and Jean-François Lejeune, Miami: Architecture of the Tropics (Center of Fine Arts; Archives d’Architecture Moderne, 1992), cover

Plate 3 Steven Brooke, Seaside (Pelican Pub. Co. Inc., 1995), cover

Plate 4 Vincent Scully, et al., Between Two Towers: The Drawings of the School of Miami (Monacelli Press, 1996), cover

Plate 5 Roberto M. Behar and Maurice Culot, Coral Gables: An American Garden City (Norma Editions, 1997), cover

Plate 6 Andres Duany et al., Charter of the New Urbanism (McGraw-Hill Professional, 1999), cover

Plate 7 Richard John, Thomas Gordon Smith and the Rebirth of Classical Architecture (Andreas Papadakis, 2001), cover

Plate 8 Rocco Ceo and Joanna Lombard, Historic Landscapes of Florida (University of Miami School of Architecture, 2001), cover

Plate 9 Charles C. Bohl, Place Making: Town Centers, Main Streets and Transit Villages (Urban Land Institute, 2002), cover

Plate 10 Jan Hochstim and Steven Brooke, Florida Modern: Residential Architecture 1945-1970 (Rizzoli, 2005), cover

Plate 11 Beth Dunlop and Joanna Lombard, Great Houses of Florida (Rizzoli, 2008), cover

(In the list of Figures and Plates)

Plate 12 Carmen Guerrero, Salvatore Santuccio, and Nicolò Sardo, Luigi Moretti: Le Ville: Disegni e Modelli (Palombi, 2009), cover

Plate 13 Allan T. Shulman et al., Miami Modern Metropolis: Paradise and Paradox in Midcentury Architecture and Planning (Balcony Press, 2009), cover

Plate 14 Galina Tachieva, Sprawl Repair Manual (Island Press, 2010), cover

Plate 15 Catherine Lynn and Carie Penabad, Marion Manley: Miami’s First Woman Architect (University of Georgia Press, 2010), cover

Plate 16 Sonia Cháo ed., Under the Sun: Sustainable Traditions & Innovations in Sustainable Architecture and Urbanism (Center for Urban and Community Design, University of Miami School of Architecture, 2012), cover

Plate 17 Rodolphe el-Khoury, Figures: Essays on Contemporary Architecture (Oscar Riera Ojeda, 2014), cover

Plate 18 Allan T. Shulman, Building Bacardi: Architecture, Art & Identity (Rizzoli, 2016), cover

Plate 19 Carie Penabad ed., Call to Order: Sustaining Simplicity in Architecture (Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers, 2017), cover

Plate 20 Tom Spain, The Drawings and Paintings of Coral Gables and Rome (Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers, 2018), cover

Plate 21 Victor Deupi ed., Transformation in Classical Architecture (Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers, 2018), cover

Plate 22 Eric Firley, Designing Change: Professional Mutations in Urban Design 1980-2020 (nai010, 2019), cover

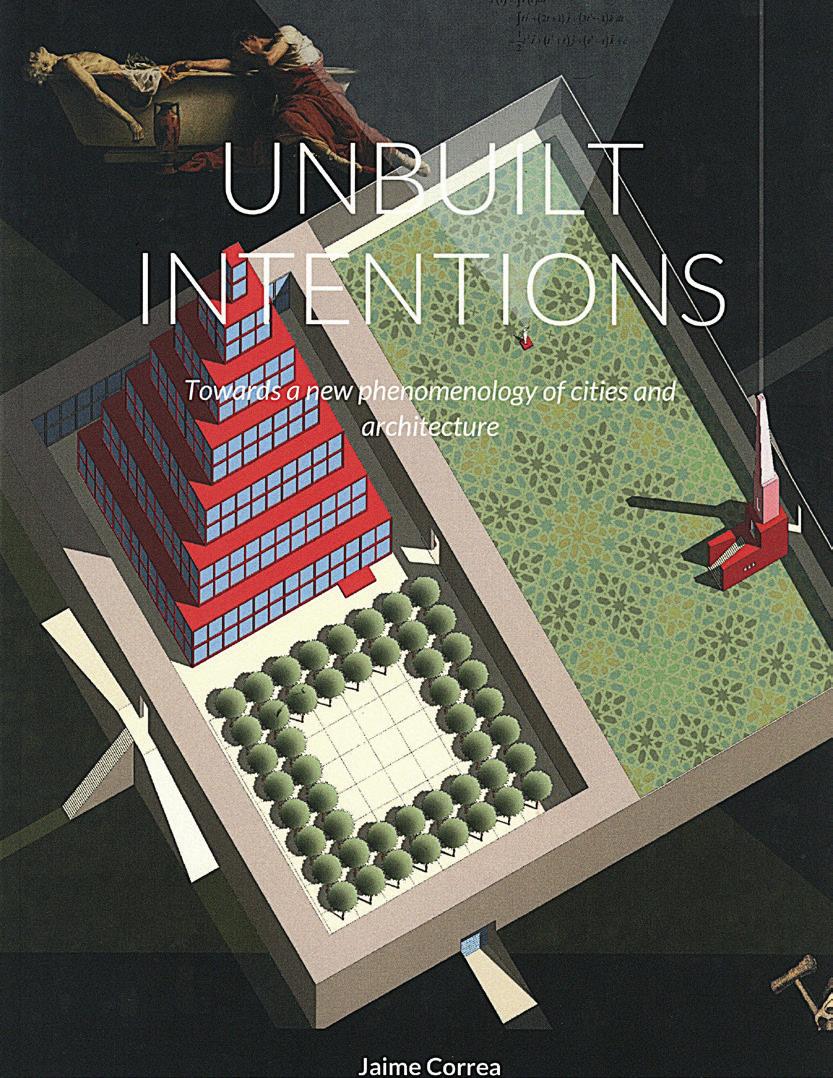

Plate 23 Jaime Correa, Unbuilt Intentions: Towards a New Phenomenology of Cities and Architecture (Lulu, 2020), cover

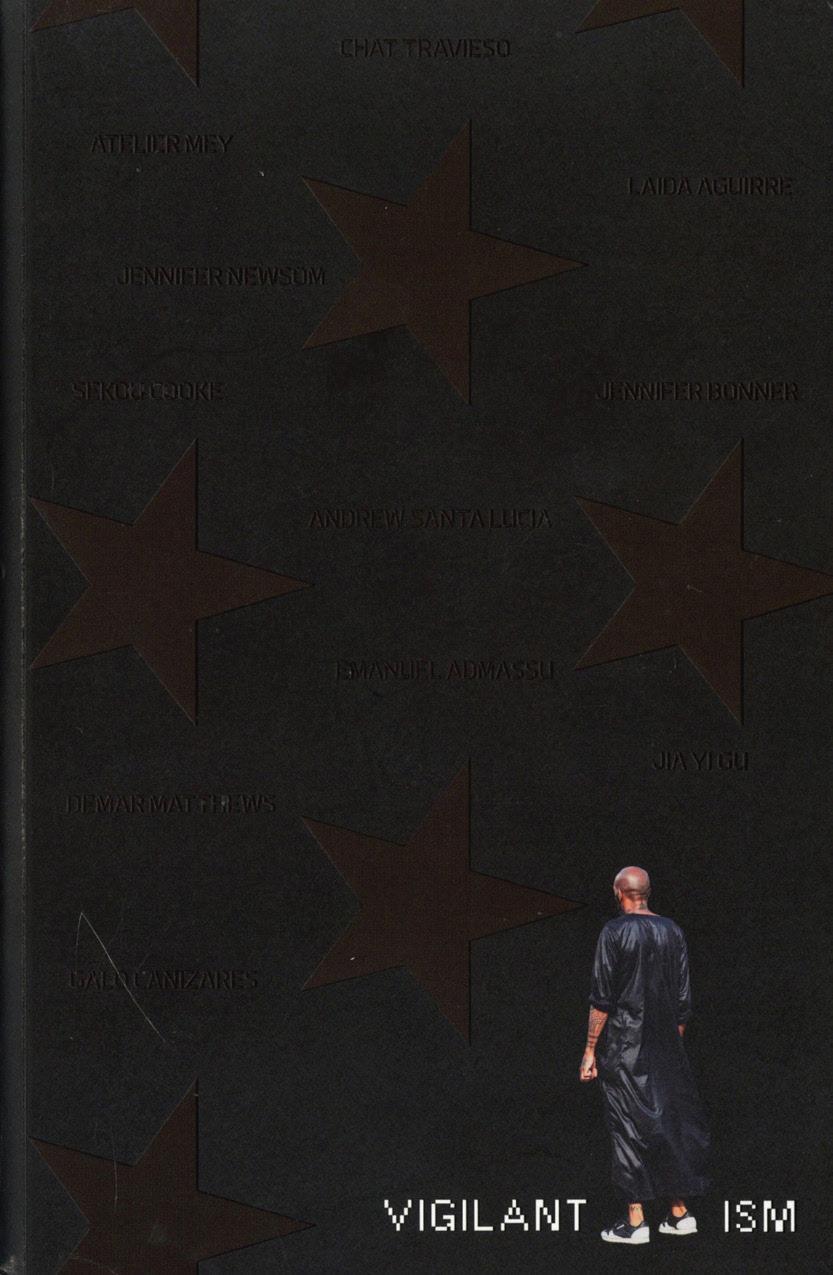

Plate 24 Germane Barnes and Shawhin Roudbari, Vigilantism (MAS Context, 2020), cover

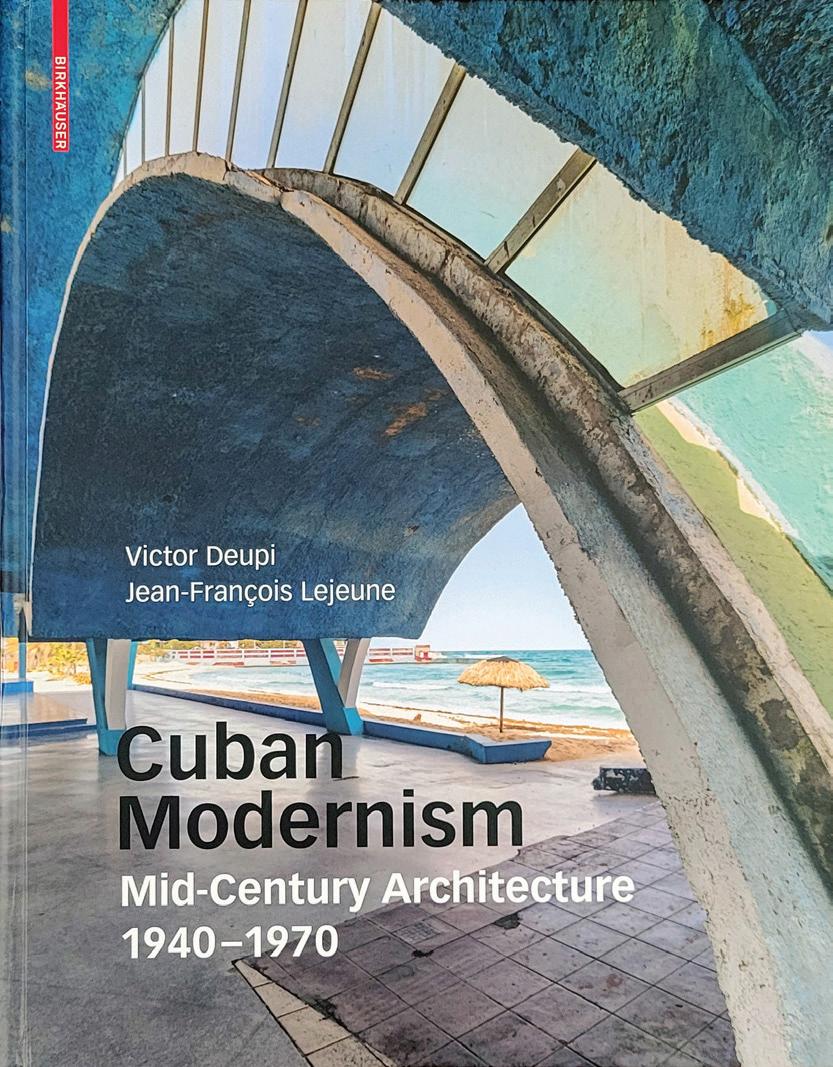

Plate 25 Victor Deupi and Jean-François Lejeune, Cuban Modernism: Mid-Century Architecture 1940-1970 (Birkhäuser, 2021), cover

Plate 26 Charlotte von Moos, In Miami in the 1980s (Buchhandlung Walther König, 2022), cover

Plate 27 Charlotte von Moos and Florian Sauter, Some Fragments (Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, 2022), cover

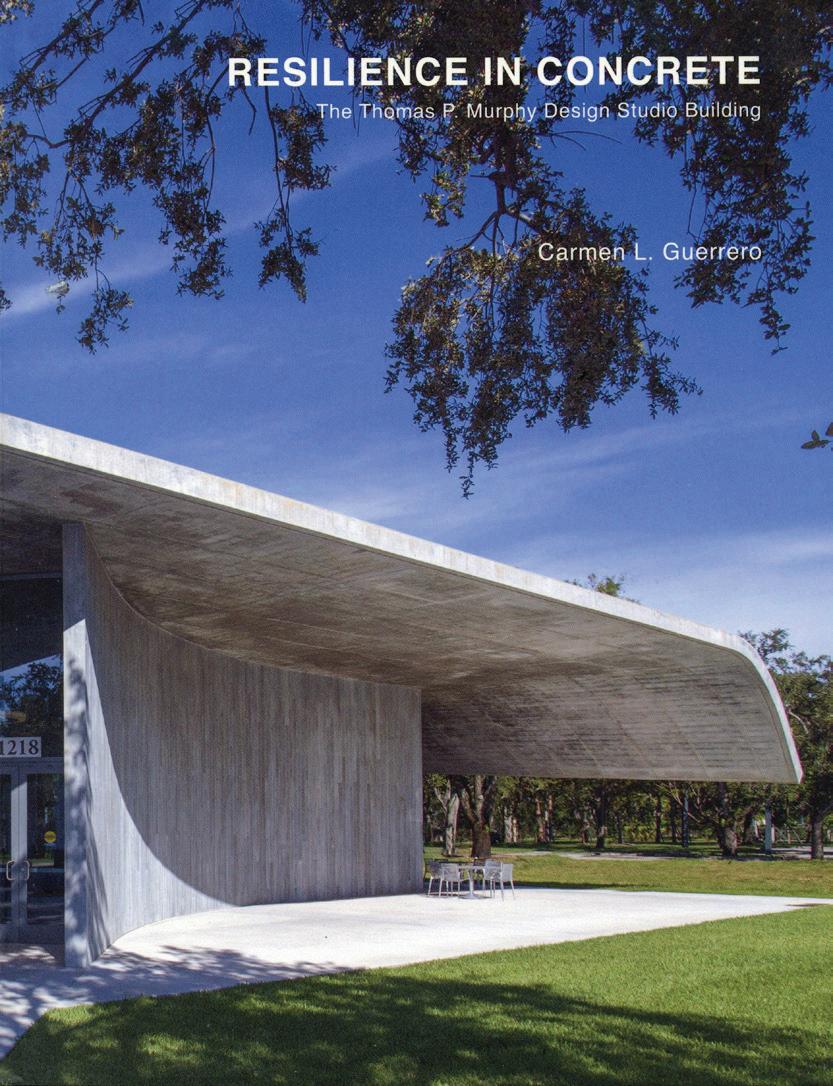

Plate 28 Carmen Guerrero ed., Resilience in Concrete: The Thomas P. Murphy Design Studio Building (Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers, 2022), cover

Plate 29 José Gelabert-Navia, Rome (Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers, 2023), cover

Plate 30 Charles Bohl and James Dougherty, The Art of the New Urbanism (Wiley, 2025), cover

Plate 31 Sonia Cháo, Calibrating Coastal Urban Resilience (Routledge, 2025), cover

Plate 32 Jean-François Lejeune, The Other Rome: Building the Modern Metropolis, 1870-1960 (Birkhäuser, 2025), cover

Plate 33 Roberto M. Behar and Rosario Marquardt / R&R STUDIOS, The Home We Share: Three Social Sculptures for Princeton University (Park Books / Scheidegger & Spiess, 2025), cover

The design of the Centennial Legacy: An Exhibition of Faculty and Alumni Publications and the associated catalog could not have come about without the collaboration of many people, or the institutional backing of the School of Architecture. I would like to thank the dean of the school, Rodolphe el-Khoury, for his encouragement and support for both the exhibition and catalog and for his thoughtful suggestions throughout the process. The school’s Centennial Task Force, chaired by Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, spawned the Exhibition Committee that has met weekly over the course of the last year to gather material and design the exhibition. Lizz has been a constant presence throughout, whose insight and thoughtfulness has made the curation and design of the exhibition infinitely more substantial and enjoyable. Gilda B. Santana, head of the Architecture Research Center, has not only shared her research on the history of the School of Architecture but has also opened the collection to us to use as needed. My research assistants, Varsha Gopal and Delayni Etienne, both graduate students in the School of Architecture, have worked meticulously on the documentation and design of the exhibition, and for that I am immensely grateful. Ivonne de la Paz, the school’s marketing specialist, has provided invaluable exhibition and book design, and communications advice. I thank everyone on the Exhibition Committee profoundly for their tireless dedication to this project.

Several School of Architecture colleagues contributed to the process at key moments, adding nuanced insights and production support. They include Roberto Behar, Madison Brinnon, Steven Brooke, Michael Cannon, Max Jarosz, Jean-François Lejeune, Allan Shulman, and Veruska Vasconez. The initial selection of published works could not have come about without Sonia Cháo’s web list of faculty publications spread across 15 categories. We reduced the categories to five and updated them with recent additions and alumni contributions. We also assembled them in chronological order to create a distinct visual presentation.

Exclusions from the exhibition or list of publications are unintentional, and for any errors or attribution failures that exist, I apologize in advance. Still, as part of the larger centennial project, we will be updating the list which will be on the school’s website. Finally, the phrase “it takes a village” comes to mind when considering the production of the Centennial Legacy exhibition, and in this case the academic village of the University of Miami School of Architecture truly does resemble an extended family over generations, all linked by a common desire to improve and enhance the built environment, one book at a time.

Victor Deupi, Ph.D.

Associate Professor in Practice

University of Miami School of Architecture

The centennial of the University of Miami offers the School of Architecture an opportunity to reflect on its legacy and its evolving contributions to the discipline. Milestones of this magnitude are often marked by exhibitions of buildings or design projects—tangible works that embody the architect’s craft. Instead, our choice to highlight books authored by faculty and alumni signals a different yet equally vital dimension of architectural education: the production of knowledge.

At the School of Architecture, we remain deeply committed to the practice of architecture and to the design of buildings and cities. That commitment defines our teaching, our research, and our engagement with communities. The university context also compels us to look beyond the building project to the ideas, histories, and theories that frame and sustain it. Scholarship and publishing are part of this endeavor. Books extend the reach of our studios and classrooms, carrying the school’s influence well beyond our community, and situating our work in broader conversations across disciplines, geographies, and generations.

This exhibition, and the catalog that accompanies it, reveal the extraordinary breadth of that scholarly engagement. The volumes represented here span history and theory, technology and sustainability, design and urbanism. They encompass studies of the Mediterranean and the Caribbean, investigations into modernism and classicism, explorations of resilience, and visions for new forms of urban life. Taken together, they remind us that architecture thrives when ideas are tested across a wide horizon, and when diverse perspectives are brought into dialogue.

Equally striking is the diversity of intellectual and ideological orientations. Our faculty and alumni pursue their work from many different vantage points and convictions, sometimes in tension with one another, but always contributing to a fertile ground of inquiry. The richness of this collective endeavor affirms that the vitality of an academic community lies not in consensus but in the coexistence of multiple voices—a setting in which, to borrow a phrase, “a thousand flowers bloom.”

In celebrating these publications, we honor not only the individuals who produced them but also the larger culture of curiosity and critical reflection that defines this school. As the University enters its second century, the School of Architecture looks forward to continuing this dual commitment: to the practice of architecture as a building project, and to the production of knowledge that expands and deepens our understanding of it.

Rodolphe el-Khoury Dean, University of Miami School of Architecture

No literary effect in the world can compare to the pure, sober taste of history. [The historian] does not want his history dry, but he does want it sec (Johan Huizinga).1

The distinguished Dutch historian Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) deftly drew the analogy between history and wine in his celebrated essay “The Task of Cultural History” (1929), suggesting that history, like excellent wine, should be appreciated more for its richness, depth, and ability to evoke a specific unique flavor, or sense of terroir (the total natural environment of any viticultural site), than as a simple chronological sequence of events.2 For Huizinga, the historian does not want to read – or drink –something so adulterated that a general historical sensibility is lost. Instead, cultural history, like great wine, requires a certain conviction or belief that it can be appreciated and understood, and that it conveys a sense that it must have been that way, and in doing so, it revives the aesthetic element in historical interpretation.3

Huizinga’s analogy offers a valuable framework for understanding the Centennial Legacy exhibition. This exhibition, presented by the School of Architecture as part of the University of Miami’s centenary celebration, showcases the rich history of professional, academic, and scholarly publications produced by its faculty and alumni since the school’s founding in 1927. Indeed, throughout its history, the University has contributed to the discipline of architecture by having its faculty engage in both professional practice and scholarly research. To that end, An Exhibition of Faculty and Alumni Publications presents for the first time a visual display of published book covers in chronological order alongside the major developments and events at the school over its first centenary. Consisting of more than 200 volumes, the exhibition covers a range of topics that include architecture, urban design, history and theory, landscape and the environment, art and design, with a considerable number having a distinct focus on South Florida. With selected volumes highlighted in greater detail, and many physical copies on view for perusing, the exhibition provides an interactive presentation of the often-solitary practice of researching and writing (Figure 1). To be sure, the exhibition should be appreciated with a delicious glass of wine.

1 “The Task of Cultural History,” republished in his collected essays Men and Ideas: History, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, trans. by James S. Holmes and Hans van Marle (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1984), 49.

2 The dry/sec distinction is of interest as most highly rated wines- whether red, white, or rosé- can be described as dry, with sweet wines that have a higher residual sugar content being the exception, Jancis Robinson, and Julia Harding, eds., The Oxford Companion to Wine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 618. On the concept of terroir, see idem, 693-95.

3 See for instance R. L. Colie, “Johan Huizinga and the Task of Cultural History,” The American Historical Review 69, no. 3 (1964): 607–30.

4 Bowman Foster Ashe, University of Miami, the First Twenty-Five Years: 1926-1951 (Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press, 1952).

5 The most comprehensive account of the school’s history is by Gilda B. Santana, “Making the University of Miami School of Architecture: Conversations with Faculty on Research, Pedagogy, and the City: 1983-2003,” Masters’ Thesis, University of Miami School of Architecture (2019). Continuous footnotes will not be given.

6 Pencil Points VIII, no. 9 (1927): 525-34, and 573.

7 See, “Whittlings,” in Pencil Points VIII, no. 1 (1927):43.

The University of Miami was originally founded in 1925 on a 160-acre site in Coral Gables donated by the City of Coral Gables founder George E. Merrick. An ambitious Beaux-Arts masterplan showed preliminary designs of Spanish revival buildings by the Miami architects Paul Chalfin (1874-1959) and Phineas Paist (1873-1937), and the artist and designer Denman Fink (1880-1956).4 Despite a devastating hurricane that decimated Miami in September of 1926, plans for the University continued forward. In 1927, the American architect John Llewellyn Skinner (1893-1972) initiated the first program of architecture at the University as a department within the College of Liberal Arts.5 A graduate of Harvard University (1921), he took an extended tour of Europe with a stay at the American Academy in Rome (1921-1922), then became head of the Department of Architecture at the Georgia School of Technology (1922-1925). In Miami, Skinner would team up with Phineas Paist and Denman Fink to form the core of the University’s new architecture faculty. The new department, the second in the state after the University of Florida, which was established in 1925, consisted of four years of study leading to a Bachelor of Science in Architecture degree, which followed the French Beaux-Arts educational system under the supervision of the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York. Students also engaged in the study of local vernacular buildings, and the early cohort also included women.

During those early years, Skinner would publish essays in the journal Pencil Points, such as “The Drawings of Bob Fink,” the son of Denman Fink and a talented artist, as well and provide updates on the new Miami program in architecture (Figures 1-2).6 At a public lecture at the Coral Gables Theater, Skinner quoted Cardinal Richelieu, “If you seek versatility, go find an architect, for he must be an artist or his buildings would offend the eye,” further suggesting that “[i]t is the architect’s duty to know … and to understand that a great deal of beauty lies in the simple mass and proportion of a building as well as in its detail.”7 This modern classical thinking was very much at the core of the new program’s mission and evident in the kinds of early publications that came out of the department’s faculty.

In addition to Skinner, both Phineas Paist and Denman Fink would engage in book and journal publications promoting Coral Gables as a kind of magical dreamscape. Paist graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (1904) and traveled through Europe, like Skinner, with extended stays at the American Academy in Rome (1911-12, 1913).8 He settled in Miami in 1916, working with Paul Chalfin and F. Burrall Hofmann at the Villa Vizcaya overlooking Biscayne Bay, and by 1923 he was an important supervising architect in the early development of George E. Merrick’s garden city of Coral Gables.9 His writings included an essay on color, and his architectural projects were featured in several early books on Coral Gables.10 Denman Fink was an American artist and illustrator who studied at the Pittsburgh School of Design, the Boston Museum of Art, and the Art Students League of New York.11 More importantly, he was George E. Merrick’s uncle, and the latter brought him to Miami in 1926 to join the Coral Gables development team not only to work on murals and drawings, but also to design entrances to the community, fountains, plazas, and the city-owned Venetian Pool. He became the head of the art department at the University of Miami, where he also taught architecture students until his retirement in 1952. Fink would contribute cover illustrations and images to several publications such as George E. Merrick’s Venetian Casino: Coral Gables (1924) and Merrick’s The Story of Coral Gables (1927), two books that promoted the new garden city with its Spanish Mediterranean imagery (Figure 4).

Skinner would also hire Ohio-raised Robert Fitch Smith as a design instructor. Smith received his degree from the University in 1931, and shortly thereafter established his architectural practice in Miami, working on residential, resort, religious, and civic buildings until his death in 1964. Fitch also published a book on his architectural projects in 1941 (Figure 5).12 In 1940, Skinner would go into architectural partnership with Harold Steward, who had previously worked with Phineas Paist, to form Steward and Skinner Associates. Among their most important works were the Miami Memorial Library in Bayfront Park (1950), and the Miami-Dade County Auditorium in Little Havana (1951).13

By the early 1930s, however, several factors including the lingering effects of the hurricane, the market crash of 1929, and the subsequent Great Depression, caused the University to reduce its scale of operation and terminate the architecture program at the end of the 1932-1933 academic year. Five students from the first enrolled class

8 The Centennial Directory of the American Academy in Rome, ed. by Benjamin G. Kohl, Wayne A. Linker, and Buff Suzanne Kavelman (New York and Rome: The American Academy in Rome, 1995), 238.

9 On his life and work, see Nicholas N. Patricios, “Phineas Paist and the Architecture of Coral Gables, Florida,” Tequesta LXIV (2004): 5-27. On the Villa Vizcaya, see Witold Rybczynski, Laurie Olin, and Steven Brooke, Vizcaya: An American Villa and Its Makers (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

10 Phineas E. Paist, “StuccoColor,” National Builder (October 1924): 46-47; Marjorie Stoneman Douglas, Coral Gables: Miami Riviera (Coral Gables: Coral Gables Corporation, 1925); and Coral Gables Today: The Miami Riviera (publisher not identified), 1926.

11 “Denman Fink Dies; Drew Gables Plans,” The Miami Herald (June 7, 1956), 1; and “Denman Fink Dead; Artist and Teacher,” The New York Times (June 8, 1956), 24.

12 Smith, Robert Fitch, The Work of Robert Fitch Smith, A.I.A., Architect, Robert S. Yeats, Associate, Miami, Florida (New York: Architectural Catalog Co., 1941).

13 “Miami Memorial Public Library,” Florida Architecture (1952): 100–102; and “Dade County Auditorium,” Florida Architecture (1953): 86–87.

14 Planos en desarrollo. Un informe especial al VI Congreso Panamericano de Arquitectura que se reunirá en la ciudad de Lima, Peru, 1947 (Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami, 1947); “University of Miami Moves Back to Boom-Bought Campus and into First Unit of AllModern Educational Plant,” Architectural Forum 89, no. 1 (July 1948): 76–82; and Carie Penabad, “University of Miami: Building a Postwar American Campus,” in Miami Modern Metropolis: Paradise and Paradox in Midcentury Architecture and Planning, ed. by Allan T. Shulman (Glendale, CA: Bass Museum of Art, 2009), 240-49.

15 “Diversity Achievement Award: Women’s Reunion + Symposium,” The School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at UrbanaChampagne (2019), n.p.

graduated in a ceremony at the Miami Biltmore Club. It was not be until after the Second World War that the University’s first president, Bowman Foster Ashe, took advantage of the U.S. government’s postwar educational programs to launch a bold vision of a modern campus.14 Ashe hired Miami architects Marion Manley, the state’s first woman architect, and Robert Law Weed to provide the University with a new master plan. Their vision was a radical departure from the 1926 plan, offering instead a flexible and functionalist approach new to University settings, seen only before at Florida Southern College in Lakeland by Frank Lloyd Wright (1938) and at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1941). It was under this bold vision of a modern university that architectural courses once again appeared in the 1950s, now in the Department of Architectural Engineering curriculum in the newly established School of Engineering.

The School of Engineering, like the Department of Architecture, had humble beginnings in the late 1920s and early 1930s. With the onset of the Second World War, however, the University expanded its engineering related courses to support the military effort. After the war, the School of Engineering was established in 1947, with a new five-year Bachelor of Science in Architectural Engineering program started in 1952 under the leadership of James Elliott Branch, who ran the program until 1968. Branch graduated from the University of Illinois in 1929 and had been an instructor in architecture there from 19311950 before joining the University of Miami, with the experience of having taught at one of the most important and long-standing architecture programs in the nation.15 With a new cohort of faculty from Illinois, Branch re-structured the program into a five-year Bachelor of Architecture in 1961, describing it as “a sequence of courses in architectural design, structural design, construction, building materials, city planning, building equipment, office practice, and the humanities.”16

During this time, the University was undergoing a radical transformation and architects such as Marion Manley, Robert Law Weed, Robert Murray Little, and Wahl Snyder were responsible for the designs of several distinctive buildings on campus. Indeed, Wahl Snyder and Darrell F. Fleeger were in charge of the new J. Neville McArthur Engineering Building, which opened in 1959. The building’s signature feature was a molded concrete sculptural screen made of diagonally cut cylinders shading walls of glass and was described by the architects as resembling a series of stacked potato chips or rippling waves (Figure 6).

16 University of Miami Bulletin (Coral Gables: The University of Miami, 1965) 249. Figure 6

During this time, architects such as Jan Hochstim, who graduated in 1954, would emerge as leading faculty

members of the program. Other faculty to join during 1960s included Paul Buisson, Felipe J. Préstamo, and Thomas A. Spain, all of whom would contribute significantly to the scholarly output of the school over the next several decades, with publications ranging from the drawings and paintings of Louis I. Kahn to the study of Caribbean and Latin American urbanization (Plate 1 & 20).17

In 1968, the architecture program became affiliated with the University’s new Center for Urban Studies, and figures such as Ralph Warburton, Joseph Middlebrooks, and Richard Langendorf introduced students to urban planning and housing, establishing the Master of Urban and Regional Planning. Middlebrooks would produce several community planning reports, including comprehensive development plans for Riviera Beach, and Opa Locka, Florida.18 Langendorf, who came from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, in Washington, D.C., would write about residential segregation and new communities from a public policy perspective.19 In this context, additions to the faculty from the 1970s and early 1980s included Tomás López-Gottardi, Aristides J. Millas, Nicholas N. Patricios, and John Ames Steffan, who would strengthen the program and initiate a robust period of academic and scholarly publications that continues to the present.20

As the program began to grow in numbers, not just in terms of faculty but student enrollment as well, the desire to separate from the School of Engineering also grew. Accreditation by the National Architectural Accreditation Board (NAAB) was achieved in 1974, allowing students to graduate with a professional degree in architecture, required for licensure. From there, independence from the School of Engineering was simply a matter of time. In 1983, department chair John Steffan urged the new University president, Edward T. Foote, to establish a separate school of architecture.21

In June 1983, the Department of Architecture and Planning officially became the University of Miami School of Architecture. The school moved from the McArthur Building to a group of international-style apartment buildings designed in 1947 by Marion Manley (Figure 7). It had an enrollment of 320 students in two programs, the five-year Bachelor of Architecture, and a two- year Masters in Urban and Regional Planning.

Following Steffan’s departure the following year to become dean at the University of Maryland, Nicholas Patricios was appointed interim dean, and a year later after a national search, Thomas John Regan was appointed the school’s first dean. The school’s emergence coincided with several intellectual strains that were shaping the critical discourse of

17 Jan Hochstim, Sketches and paintings of Louis I. Kahn, analysis and Catalog raisonné (Thesis, Dissertation, University of Miami, 1976), later published as The Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn (New York: Rizzoli, 1991); and Felipe J. Préstamo y Hernández, Plan for the Coordination of Transportation Services: Dade County, 1981-1985 (Miami, FL: United Way of Dade County, Area Agency on Aging for Dade and Monroe Counties, 1981).

18 Joseph Middlebrooks, Comprehensive development plan: capital improvement program, Riviera Beach, Florida (Miami, Fla., Urban Planning Studio, 1975); and Comprehensive development plan for the City of OpaLocka (Miami, FL, Urban Planning Studio, 1978).

19 Richard Langendorf, New communities--the American experience: a discussion paper (Coral Gables, University of Miami Center for Urban and Regional Studies, 1973); and Richard Langendorf, Arthur L. Silvers, and Rodney P. Stiefbold, Residential segregation and economic opportunity in metropolitan areas (Coral Gables, Fl and Springfield, Va: National Technical Information Service, 1976).

20 See for instance, Aristides J. Millas, and Claudia M. Rogers, The Development of Mobility Criteria for the Elderly: Within the Context of a Neighborhood: An Interdisciplinary Research Project Supported by the University of Miami Institute for the Study of Aging (Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami, 1979); and Nicholas N. Patricios, and Aristides J. Millas, Coral Gables Central Business District Study: An Academic Community Service Project (Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami, 1983).

21 Steffan had previously published along with Horacio Caminos, and John F. C Turner, Urban Dwelling Environments: An Elementary Survey of Settlements for the Study of Design Determinants (Cambridge, Mass: M.I.T. Press, 1969).

architectural education at the time. The increasing interest in history and theory, the elaboration of architectural representation, environmental concerns, and the recognition that architecture and urban design are reciprocally related were shaping a contemporary pluralism, challenging the foundations of international modernism, the Bauhaus, and any form of structural or functional determinism.

The influence of Europeans played an enormous part in transforming the School of Architecture’s vision in the mid-1980s. Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City, first published in 1966 and reprinted in multiple languages worldwide, and Maurice Culot and Léon Krier’s Rational Architecture: The Reconstruction of the European City (1978), encouraged a rediscovery of the traditional European city.22 Rossi came to the University of Miami in 1986 to design a new campus for the School of Architecture, a highly publicized work that was never built (Figure 8).23 Conceived as an academic village based on his concept of the basic typologies that constitute a city, the plan had an enormous impact on the school’s burgeoning intellectual focus on design, history, city planning and civic activism, ecology, and the conservation of vernacular forms, giving the school a unique identity among North American programs in architecture.

22 The English edition was first printed in 1982 and published by Opposition books under the editorial leadership of Peter Eisenman. The full title of Krier’s book was Rational Architecture: The Reconstruction of the European City = Architecture Rationnelle: La Reconstruction de La Ville Européenne (Brussels: Éditions des Archives d’architecture moderne, 1978).

23 See the “Aldo Rossi Proposal for University of Miami School of Architecture,” Architecture Research Center, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, FL (1987).

The faculty at the School of Architecture, which now included a third wave of new hirings, responded with a strong output of architectural design and critical thinking through many built works and publications. It was in the 1980s that study abroad emerged with programs in Venice, then Rome, offering students similar “Grand Tour” experiences to what Skinner and Paist experienced in the 1920s, and what Rossi and Krier were encouraging architects to consider more directly. Also, in 1988 the Master of Architecture in Suburb and Town Design was initiated to promote the idea of architecture as a civic art. In the wake of this new program, the school launched its first journal, The New City, which was published in three editions from 1991-1996 under the editorial supervision of faculty member Jean-François Lejeune (Figure 9).

The school’s interest in the cultural continuity of traditional architecture and urbanism caught the attention of architectural historian Vincent Scully, whose student at Yale in the 1950s had been University President Edward Foote. Scully was invited to teach at the School of Architecture as a distinguished visiting professor in 1991. He would teach both at Yale and the University of Miami until his retirement in 2009. The 1996 publication of Between Two Towers: The Drawings of the School of Miami, by Scully with contributions by faculty members Jorge Hernandez, Catherine Lynn, and Teofilo Victoria, featured students’ remarkable drawings and watercolors, bringing further national and international attention to the school (Plate 4).24

Faculty publications reflecting the many facets of the school and architectural thinking at the time increased in volume and scale. Works such Towns & Town Making Principles (1991), documenting the Harvard exhibit of the work of Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk; Maurice Culot and Jean-François Lejeune’s Miami: Architecture of the Tropics (1992); and Roberto Behar’s Coral Gables: An American Garden City (1997) all brought to light the importance of South Florida’s urbanism and the unique presence of the school within its historical context (Plates 2 & 5). Hurricane Andrew, which ravaged South Florida in August of 1992, encouraged faculty to engage in community activism, resulting in its documentation in The New South Dade Planning Charrette: From Adversity to Opportunity (1992), produced by Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and Sonia Cháo, who subsequently established the school’s Center for Urban and Community Design under the auspices of dean Roger Schluntz.

The late 1990s and early 21st century brought many changes to the architectural campus, including new buildings and deans. The Jorge M. Perez Architecture Center by Léon Krier in conjunction with Merrill Pastor & Colgan Architects of Vero Beach, and the firm of Ferguson Glasgow Schuster Soto of Coral Gables, opened in 2005 (Figure 10). Alumna Nati Soto worked with Krier to produce the Perez Center, which includes Glasgow Hall, commemorating the initiating gift of her partner. The B.E. and W.R. BuildLab designed by Professor Rocco Ceo (Figure 11) and the Thomas P. Murphy Design Studio Building, designed by the Miami firm Arquitectonica followed in 2018 (Figure 12). Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk became dean in 1995 and remained in place until 2013 when she was succeeded by the current dean, Rodolphe el-Khoury (2014-present).

Many new architects from across the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa have joined the faculty, representing the pluralism of contemporary architecture while still acknowledging the school’s historic approach to urbanism and the rich context of South Florida.

This diversity reflects clearly in the many publications produced in the last 25 years, beginning with Richard John’s Thomas Gordon Smith and the Rebirth of Classical

24 Vincent Scully, et al., Between Two Towers: The Drawings of the School of Miami (New York: Monacelli Press, 1996).

25 This material will also be compiled and made available during the exhibition, though not as prominently as the book publications.

Architecture (2001), and Rocco Ceo and Joanna Lombard’s Historic Landscapes of Florida (2002). There followed The New Civic Art (2003), with multiple faculty and alumni authors, Jan Hochstim and Steven Brooke’s Florida Modern (2005), Allan T. Shulman’s (ed.) Miami Modern Metropolis (2009), Catherine Lynn and Carie Penabad’s Marion Manley (2010), Eric Firley’s Urban Housing Handbook (2011, and revised 2023), Nicholas Patricios’ The Sacred Architecture of Byzantium (2013), Rodolphe el- Khoury’s Figures: Essays on Contemporary Architecture (2014), Germane Barnes’ Vigilantism (2020), Charlotte von Moos’ In Miami in the 1980s (2022), José Gelabert Navia’s Rome and Coral Gables (both 2023), and Jean-François Lejeune’s, The Other Rome: Building the Modern Metropolis 1870-1960 (2025), among many others (Plates 7, 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 24, 26, 29 & 32).

It should be noted that the intellectual focus of the school has not been strictly limited to Europe and North America but is equally concerned with the Caribbean and Latin America. Beginning with Jean-Francois Lejeune’s Cruelty & Utopia: Cities and Landscapes of Latin America (2005), a recipient of the International Committee of Architectural Critics (CICA) Julius Posener Exhibition Catalog Award, and followed by Kenneth Treister, Felipe J. Préstamo, and Raúl B. García’s Havana Forever: A Pictorial and Cultural History of an Unforgettable City (2009); Adib Cure and Carie Penabad’s Barranquilla: Redefining the Urban Center (2009); Sonia Cháo’s Under the Sun: Sustainable Traditions & Innovations in Sustainable Architecture and Urbanism (2012); Allan Shulman’s Building Bacardi: Architecture, Art & Identity (2016); and Victor Deupi and Jean-François Lejeune’s Cuban Modernism (2021), several School of Architecture faculty have brought to light the critical importance of the American north/south axis (Plates 16, 18, 25).

In addition, a reflection of the school’s wide publishing interests are the works of alumni authors (Plates 14 & 30). Galina Tachieva published Sprawl Repair Manual (2010), and Hermes Mallea published Great Houses of Havana (2011) and Havana Living Today (2017). Victor Dover co-authored Street Design (2014), Andrew Cogar published Visions of Home (2021), and more recently James Dougherty and Chuck Bohl (faculty member since 2000) edited The Art of the New Urbanism (2025). Finally, it should be mentioned that books are not the only form of publications faculty and alumni have produced. There are many scholarly essays, book chapters, reviews, exhibition catalogs, pamphlets and documents, newspaper articles, and online blogs and podcasts that increase the growing list of scholarly work exponentially.25

As the University of Miami embarks on its second century, it is safe to say that scholarly publications will remain at the forefront of the intellectual work produced by faculty and alumni of the School of Architecture. And no doubt, new and unpredictable forms of published work will emerge, adding to the many ways that curiosity and critical thinking about the built environment can reach the wider public. Media will change, and the modes of transmission will inevitably evolve with it, but the writing will never stop!

The following titles have been selected from the exhibition and highlighted in much greater detail, providing viewers of the exhibition with a more interactive and nuanced experience of what it takes to produce a scholarly book and market it commercially. Book reviews, publishers’ descriptions, and personal anecdotes add to the viewer’s experience and underline the fact that as in architectural design, book publication requires a team effort.

26 “Review of The Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn, by J. Hochstim,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 52, no. 1 (1993): 115–18.

The Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn. Rizzoli, 1991

Hochstim’s book, The Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn, is the first complete collection and study of the artistic work created by the renowned 20th-century Estonian-born American architect Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974). Before he became famous for his many buildings and projects, Kahn produced an extensive collection of paintings, sketches, pastels, watercolors, and oil paintings, largely from his North American and European travels, particularly at the American Academy in Rome in 1950. His artwork, which includes landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and cityscapes, evolved over time, ranging from modern illustration and realism to the more abstract and stark pieces he produced later in his career. Hochstim’s book is arranged in chronological order, with a description and analysis for each of the 480 known artworks. In addition to the catalog, the book contains a detailed analysis of how his art influenced his architecture, a biography, a comprehensive bibliography, and an introduction by Vincent Scully, a leading authority on Kahn and University of Miami visiting professor.

Jan Hochstim’s The Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn, with 480 major illustrations in the Catalog section, is the most comprehensive collection of Kahn’s artistic work yet published.

It is based on the author’s master’s thesis (University of Miami, 1976), which included a two-day interview with Kahn in 1972 … Kahn’s drawings, like those of other great architectural draftsmen (Le Corbusier’s sketches were a major source of influence), attempt to capture the essence of his subjects; they become increasingly re-compositions and re-creations of reality rather than photographic renderings (Fikret K. Yegul).26

Miami: Architecture of the Tropics. Center of Fine Arts; Archives d’Architecture Moderne, 1992

Brief Description

Maurice Culot and Jean-François Lejeune’s book, Miami: Architecture of the Tropics, served as the catalog for an exhibition of the same name that was held at the Center for the Fine Arts in Miami from December 19, 1992, to March 7, 1993. The exhibition was a collaboration between the Fondation pour l’Architecture in Brussels and the University of Miami’s School of Architecture. The book includes a foreword by Mark Ormond (director of the Miami Center for the Fine Arts), an introduction by Caroline Mierop (curator of the exhibition), and essays by Maurice Culot (president of the Fondation pour l’Architecture), Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater- Zyberk, and Jean-François Lejeune. The content explores modern tropical architecture, which is a design approach that uses passive strategies to minimize heat and promote air circulation in response to a tropical climate. The book reveals how Miami architects have successfully addressed the challenges of designing residential, commercial, and institutional buildings that harmonize with the tropical environment and topography of South Florida.

Author’s Comments

1992: the summer of the destruction of Hurricane Andrew. Yet, it was also a seminal fall with the publication of the special issue “Miami” of the Italian periodical Abitare in November 1992 and one month later, the opening of the large exhibition Miami Architecture of the Tropics at the Center for Fine Arts (now PAMM). The accompanying book was edited jointly by Jean-François Lejeune and historian, author, and urbanist Maurice Culot. Invited at the school as visiting critics, Mierop and Culot discovered and explored both Miami’s architectural history and its new architecture—much of it involving the faculty— being thought up and built in continuation of the three traditions of Miami discussed by Duany and Plater-Zyberk: the Cracker vernacular, the Mediterranean Revival, and the Modernist. Also on display was Aldo Rossi’s project for the new school of architecture. Sadly unbuilt, it attracted disappointed visitors for many years (Jean- François Lejeune).

For the historian the most interesting chapter is the somewhat tongue-in-cheek work “The Three Traditions of Miami” by Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, probably America’s most innovative contemporary urban planners … In “Dream of Cities,” JeanFrançois Lejeune, also associated with the University of Miami School of Architecture, discusses urbanism in the last years of this century … This is a beautifully designed book with many striking color photographs. It is at its best, as was the exhibit, in detailing the contemporary work of the young architects of Miami (Donald W. Curl).27

27 “Review of Miami: Architecture of the Tropics,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 72, no. 4 (1994): 515–17.

Steven Brooke’s book Seaside is a photographic guide and documentation of the Florida resort town of the same name, designed by Andres Duany and Plater-Zyberk (with others) in 1981. The book details how the town evolved from its origins as an idea—by founder Robert Davis—of a traditional seaside village on the water to a model for the New Urbanism movement. The book is heavily illustrated with Brooke’s extraordinary architectural photographs, which capture the essence and design of the town. Moreover, the book serves as a guide to Seaside, providing a comprehensive look at the town’s buildings, including some of its most beautifully designed homes. Brooke’s text describes the specific architectural elements that define the “Florida style” as seen in Seaside. This includes features like tin roofs, picket fences, and large porches, which all contribute to the town’s Southern vernacular character. The book also highlights the urban design principles of New Urbanism, such as walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. Through his photography and text, Brooke documents Seaside’s growth from its “earliest pioneer stages” with dirt roads and simple cottages to its development into a thriving community with award-winning houses and public buildings.

From Seaside’s inception, I was asked to serve as its photographer of record. To my knowledge, no photographer—past or present—has had such an opportunity. Piranesi and Vasi documented 18th-century Rome already in decay. Canaletto, Marieschi, and Bellotto depicted Venice in its static grandeur. David Roberts portrayed a relatively changeless Holy Land, while Vermeer and de Hooch captured fragments of Dutch towns. Even my earlier work in Miami Beach recorded an existing district undergoing modest transformation. Seaside, by contrast, offered something wholly different: the chance to document, from the very beginning, a community destined to become a landmark in architectural and urban history.

I understood that the world would first encounter Seaside largely through my photographs. At a time when its simple coastal cottages were derided by critics as “Tobacco Road shacks,” it was essential to present them with the same disciplined eye I applied to works of greater size, cost, or pedigree. My responsibility was not only to ennoble these modest structures but also to convey Seaside’s larger vision: the human scale of its streets, the careful arrangement of its buildings, and the presence of iconic beach pavilions rather than high-rises at street termini. The way each view was framed became critical to communicating both what was there and what was to come (Steven Brooke).

Contributions by Jorge Hernandez, Catherine Lynn, Teofilo Victoria Between Two Towers: The Drawings of the School of Miami. Monacelli Press, 1996

Brief Description

This exceptionally elegant publication combines the work of the students and faculty of the University of Miami School of Architecture with a text by the school’s distinguished visiting architectural history professor, Vincent Scully, from Yale University. The School of Architecture is known for its whimsical and analytical drawings of architecture, urban planning, and landscape design, illustrating the natural and man-made environment, animals and objects, and plans for designing and reinventing built and unbuilt cities. Miami’s principal urban centers and surrounding environments are apparent in the students’ work, with vivid colors echoing the spirit of Coral Gables, Key West, and the Everglades. Miami’s vital position as a major nexus of the greater Caribbean world is also evident, as the drawings embrace the cultural richness of the West Indies and Central and South America in both subject matter and style. Imaginatively designed, Between Two Towers features a horizontal, sketchbook-like format with gatefold pages, capturing the incredible detail, complexity, and scale of the student and faculty drawings, some reaching 10 feet in height and length. The drawings come in a variety of media, including graphite, colored pencil, ink, and watercolor. Scully’s informative text recounts the school’s history and documents the distinctive teaching approach of its faculty.

Contributor’s Comments

In this provocative and highly visual work, Scully casts the drawings and attendant pedagogy of the University of Miami School of Architecture to counterpose prevailing trends in Modernism as a critique which “…involves, before all else, the development of a special kind of drawing, one which, by the late years of the 20th century, has begun to affect the course of contemporary architecture profoundly, has begun to restore architecture… to its former glory as the shaper of the human community, as the fundamental intermediary between humanity and nature’s invincible laws.” (Scully pg. 9)

Scully and Lynn first saw the drawings in process in 1990 in New London, Connecticut, where Professors Hernandez and Victoria, with Jorge and Luis Trelles and Frank Martinez in assistance and their students, began testing and putting together the methodology of the summer traveling studio at the invitation of former chair and the school’s founder, John Steffan, in an old barn he lent. There, under the hay lofts and rafters, the students drew, documented and analyzed the structure and iconography of New England’s townscapes, landscapes, and monuments. They drew as an act of respect, of deference to the place where they would later site their designs.

28 “Drawing to Understand,” The Chronicle of Higher Education 43, no. 31 (Apr 11, 1997): 1.

This studio was born as a reaction to the explosive global colonization of the “Local” fostered by the phenomena of “Starchitecture,” which treated site as a petri dish for gargantuan “follies” from the egos of whomever the prevailing star might be at any given time. The program grew and continued over many summers to distinct and distant places. Scully and Lynn joined the faculty in 1991 and taught at Miami every winter term for nearly 20 years. The traveling summer studio – now the “Open City Studio”—has continued under a new generation of faculty, Adib Cure, Steven Fett, Carie Penabad, and Edgar Sarli, where the experiment, its intellectual progeny, and Scully’s insight have been memorialized in the school curriculum and pedagogy to this day (Jorge Hernandez).

Ten years after being elevated from a department in the engineering school to become the School of Architecture (1983), a visual identity was coalescing amidst national recognition of the school’s special character. This became the subject matter for Between Two Towers: The Drawings of the School of Miami (1996). Instigated by architecture historians Vincent Scully and Catherine Lynn shortly after they joined the faculty, the images and text represent a foundational time in the school’s history. The work reflects a renewed international appreciation for architectural drawings and the faculty’s growing awareness of the cultural—read local and historical—context for buildings, landscapes, and cities. From historical documentation to interpretative images of character and identity, to design projects in the studio and in budding professional practice, the subject matter concerns place-making a focus for that emerging movement called the New Urbanism.

Escaping the continental antipode of South Florida, and in search of a deeper history, the peripatetic (young) faculty took students to points north and abroad – New England, Venice (hence the reference to Ruskin), the Caribbean (with the Mediterranean a single discontinuous sea), Latin America, and Japan. Often the travelers’ resource limits inspired inventions of subject matter and technique. Keen observation and precision in skills encouraged, many students produced the first beautiful drawing of their career (Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk).

Something very like (John) Ruskin’s fever of drawing animates the School of Architecture at the University of Miami. From the moment undergraduates arrive, they are pushed to draw freehand. Close by, they draw the works of architects, the local products of their profession and the works of nature, the palms, ficus, and live oak trees that press right up to studio windows, the leaves, blossoms, and fruits that instantly appear on drafting tables. Promptly students find themselves in the Everglades, in the citrus groves, in the agricultural Redland of South Florida, drawing, drawing, as are the young instructors at their sides. And they continue to do so for their full five years, dodging the traffic of downtown Miami, the skateboarders on South Beach, the tourists in Key West. A great many travel with their ever-drawing mentors to the ancient Spanish towns of the Caribbean and Central and South America. And some go to Rome. They can amaze even themselves with the pictures they bring back (Catherine Lynn).28

Roberto M. Behar and Maurice Culot

Contributors: Maurice Culot, Elizabeth Guyton, Joanna Lombard, Roberto M. Behar, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Vincent Scully

Coral Gables: An American Garden City. Norma Editions, 1997

Publisher’s Description

In 1921 a visionary entrepreneur, George E. Merrick, decided to build the most beautiful garden city in the world eight kilometers southwest of Miami, on the site of a family lemon plantation: Coral Gables, named for the coral stone used for the prominent gable of the Merricks’ first house. Surrounded by a stone wall pierced by monumental gates, Coral Gables, with its trees, its shaded paths, its fountains, actually corresponds to the dream of its creator. The beauty and extravagance of the place is based on unforgettable monuments: the picturesque Venetian swimming pool from 1924, a mecca of social life where Esther Williams frolicked and where Johnny Weissmuller, alias Tarzan, made his debut as a master swimmer; the Biltmore Hotel with its tower inspired by the Giralda of Seville; the baroque churches supposed to recall the Californian Catholic missions intended to evangelize the Indian populations; and the unique network of canals that connect the city to Biscayne Bay, populated in the 1920s with authentic gondolas.

Author’s Comments

Working on Coral Gables: An American Garden City gave me the opportunity to explore and uncover the unique and fascinating history behind the making of Coral Gables. The city’s distinctive approach to uniting architecture, landscape, and urban design into an artistic civic endeavor shaped everything I pursued thereafter. Collaborating with Maurice Culot, founder of the remarkable Archives d’Architecture Moderne in Brussels, and editor of numerous influential books on architecture and cities, I discovered the joy of telling architectural stories through beautiful and meaningful publications. His lessons, along with the gift of his enduring friendship, remain treasures I will always cherish (Roberto M. Behar). Plate 5

Michael Leccese and Kathleen McCormick, eds.

Contributors: Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Galina Tachieva, et al.

Charter of the New Urbanism. McGraw Hill, 1999

Publisher’s Description

The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) is the leading organization promoting walkable, mixed-use neighborhood development, sustainable communities, and healthier living conditions. Thoroughly updated to cover the latest environmental, economic, and social implications of urban design, Charter of the New Urbanism features insightful writing from [multiple] authors on each of the Charter’s principles. Real-world case studies, plans, and examples are included throughout.

This pioneering guide explains how to restore urban centers, reconfigure sprawling suburbs, conserve environmental assets, and preserve our built legacy. It examines communities at three separate but interdependent levels:

• The region: Metropolis, city, and town

• Neighborhood, district, and corridor

• Block, street, and building

Featuring new photos and illustrations, this practical, up-to-date resource is invaluable for design professionals, developers, planners, elected officials, and citizen activists.

Author’s Comments

The Charter of the New Urbanism is an elaboration of the manifesto of the same title that defines the principles of New Urbanism. The book’s 27 chapters, each written by a founding member of the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU), explain the 27 principles of the charter. These are organized by a gradation of the built environment: Region, Metropolis, City, and Town; Neighborhood; Street, Block, and Building. These reflect the expertise of the organization’s founders: Calthorpe, proponent of regional plans in California and Oregon; Duany and Plater- Zyberk, designers of new neighborhoods and towns in Florida and Maryland; Moule, Polyzoides and Solomon, designers of urban housing in California.

The Congress for the New Urbanism was founded in 1993, a year after a meeting in Alexandria, Virginia of architects, landscape architects, planners, traffic engineers, attorneys, civic activists, and others, determined that an organization was needed to

advance knowledge and experience in a unified manner, to address the problems of suburban sprawl and urban disinvestment as “one interrelated community-building challenge.”

The charter was written in 1996 and at the CNU meeting in Charleston signed by all the attendees, including then secretary of United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Henry Cisneros and many faculty members of the University of Miami School of Architecture. The book was published in 1999; a second edition followed in 2013. The charter has been translated into more than a dozen languages, which can be accessed on the organization’s website www.cnu.org (Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk).

Planners can stop grumbling. The Charter of the New Urbanism has arrived: a bold, visionary, fleshed-out statement of the original set of principles put forth by the Congress of the New Urbanism in their earlier Ahwanhee Principles. Here is planning’s emancipation proclamation of freedom from postmodern relativity: Planning, it seems, is not entirely about process. There are, in fact, some fairly concrete principles that can be adhered to, and, in this document, no less than 27 urban designers, architects, politicians, and even a few planners have stepped forward to lay down the law of good city form. This is not to say that change, diversity, and participatory process are not an integral part of their statement.

The significance of the charter must be judged from two perspectives. From the point of view of planning academicians, it represents a bold statement insofar as it is unabashedly normative: It asserts, in resolute terms, what the basis of beauty in urban planning is. Here, beauty is not entirely within the eye of the beholder. Instead, it is centered on the values of truth and goodness in urban form, ideals that are knowable, manifested in specific aesthetic principles of spatial organization. Yet the boldness of this ideal is probably perceptible only if one is looking from the academic point of view. For a majority of practicing planners, the charter undoubtedly represents a composite summary of the kinds of principles they have tried (ineffectively, for the most part) to pursue on a daily basis. There is hope here for realization of these principles, since the New Urbanists expertly tie together an amalgam of many widely held beliefs about what a good pattern of development is supposed to be and how it can be sustained (Emily Talen).29

29 “Charter of the New Urbanism: Valuing the New Urbanism: The Impact of the New Urbanism on Prices of Single-Family Homes,” Journal of the American Planning Association 67, no. 1 (Winter, 2001): 110-12.

Thomas Gordon Smith and the Rebirth of Classical Architecture. Andreas Papadakis, 2001

Publisher’s Description

Thomas Gordon Smith has played a central role in the revival of classicism in contemporary architecture in America. In the late 1970s he became a key figure in the development of PostModernism but after contributing to that movement’s seminal exhibition at the 1980 Venice Biennale, he rejected the ironic approach of Robert Venturi and the decontextualization of Charles Moore to develop an architecture that draws freely on the 25 centuries of the classical tradition. His conviction in the enduring relevance of the tradition to contemporary life has resulted in buildings that in terms of materials and function are just as much a product of the modern world as a high-tech office building or a Deconstructivist museum extension, but in addition to admirably fulfilling the job for which they were intended, they also have the rare quality of engaging us intellectually. This extensively illustrated monograph presents Thomas Gordon Smith’s buildings and projects for the first time. A biographical essay explores the polymathic range of his other activities, including his influential role as an educator, commentator on Vitruvius, historian of the Greek Revival, painter of frescoes, and designer and collector of furniture.

Author’s Comments

In August 1994 I was asked to speak at a symposium on contemporary classical architecture held at a stunning new seaside villa in the Peloponnese, which had been designed and built by the expatriate American artist Charles Shoup. At the time I was a fellow of Merton College, Oxford, where I taught medieval and Renaissance Italian history. I had recently completed a three-year stint as a thesis tutor at the Architectural Association School of Architecture while completing my PhD at the Warburg Institute. The villa had its own private beach and so, at the first break in the proceedings, I leapt at the opportunity to have a cooling dip in the Mediterranean; when I emerged from my swim I encountered a figure sitting on a rock at the edge of the beach hunched over a sheaf of papers, furiously making notes. It was Thomas Gordon Smith, one of the participants in the symposium, at work on his commentary on Vitruvius. The University of Notre Dame had hired him five years previously to transform its architecture program into a new classical architecture school, the first to operate in the United States for many decades, and his intense study of Vitruvius was part of that endeavor. A few months after the symposium, the Prince of Wales invited me to become the director of his Institute of Architecture in London, so over the next three years, as the head of the only traditional school of architecture in the UK, I naturally turned to Thomas to collaborate

on a number of initiatives: I asked him (and several members of his faculty) to teach on the Summer Schools I organized for the prince in the United States and he, in turn, invited me to speak at Notre Dame and in a lecture series he organized in Russia at the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts.

In early 1998, following the dramatic shift in British popular sentiment against the Royal family in the wake of Diana’s death, it was announced that Prince Charles would curtail what were perceived to be his most publicly controversial activities and, consequently, the professional architectural program at his Institute of Architecture would be wound down. Finding myself, unexpectedly, with time on my hands and keen to continue contributing to the intellectual project of reviving a classical pedagogy, I asked Thomas if he would be willing to be the subject of an architectural biography. Over the next few months, with long interviews conducted by telephone and working closely with Thomas and his wife Marika, who ran his architectural office, to gather images, the publication took shape. The timing was fortuitous because Andreas Papadakis, the Greek Cypriot publisher whose imprint Academy Editions had played a crucial role in the international architectural debates of the 1970s and 80s, was itching to return to the business now that the non-competition clause imposed as part of the sale of his publishing house to Wiley-VCH had expired. The result was this book: Thomas Gordon Smith and the Rebirth of Classical Architecture (Richard John).

Praise

Richard John admirably conveys the fey qualities of Smith’s work, skipping around the edges of antiquity, at once faun-like and sacerdotal, Etruscan and Early Christian, exuding innocence, strangeness, and abandon, and always suggesting a variety of religious experiences (Vincent Scully).

Thomas Gordon Smith, perhaps the most intellectually stimulating of the traditional and classical architects at work today in the United States, has found in Richard John the ideal biographer. As in the plot of a first-class detective story, we follow the careful construction of a career through the analysis of a complex weave of contrasting social, intellectual and architectural conjunctions, including Thomas Gordon Smith’s meetings with figures as varied as Paolo Portoghesi, Christian Norberg Schulz, Philip Johnson, and Stanley Tigerman. The result, rich with illustrations of stunning beauty, is one of the most remarkable biographies of any modern architect (David Watkin).

Review

Smith, of the School of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame, was in the 1970s a key figure in the postmodernist and decontexualist movements, but he has moved on, having rediscovered the imaginative richness of the classical tradition. This handsome book provides an engaging account of what he thinks architecture can again be, along with striking illustrations of his work, including private houses, civic buildings, and churches. If it is true that we are, in significant part, the spaces in which we live, Smith points to a future of greater human flourishing.30

30 “Thomas Gordon Smith: The Rebirth of Classical Architecture.” First Things: A Monthly Journal of Religion and Public Life (February 2003): 65.

Historic Landscapes of Florida. Deering Foundation and the University of Miami School of Architecture, 2001

Brief Description

Historic Landscapes of Florida by Rocco Ceo and Joanna Lombard is a book that documents and analyzes significant historic landscapes across the state of Florida. The book is the result of a decade-long project where the authors, in collaboration with students from the University of Miami, created a record of Florida’s important and often threatened landscapes. The book also highlights the need to understand these spaces as meaningful cultural resources. Moreover, the authors explore how these landscapes are not just natural areas but are interconnected systems that reveal the history and aspirations of the people who shaped them. They argue for the conservation and preservation of these sites, to build public awareness and encourage advocacy for their protection. Finally, the book also delves into the design principles behind these historic landscapes, often revealing the work of visionary landscape architects who artfully orchestrated site planning, landscaping, and architecture to create a true sense of place.

Judging a book by its cover, Historic Landscapes of Florida suggests a broad regional topic, with only a hint at its method. What is less obvious is the extensive primary research undertaken by the slow and careful process of documenting the landscapes and its architecture—to scale. This work, carried on by students over many years, teaches architecture students about how to use drawing as a research method. The images form more than a catalog of these landscapes; they are explorations in new ways of representing the intimate relationship found between landscape and architecture. Many landscapes, drawn for the first time here, became tools of preservation for their stewards, and 24 years later, a record of change. A moment in time that captures how architecture education was both learning the tools of the profession and simultaneously producing new knowledge for future generations (Rocco Ceo).

If it weren’t for a series of timely associations, I am not sure this book would have happened! I had been documenting and studying American gardens and their European precedents through a Wheelwright Fellowship and continued that work here at UM with students, while also studying the Florida work of William Lyman Phillips, an Olmsted protégé. Rocco had been documenting cultural landscapes in Florida. Javier Cenicacelaya was the dean at the time, and he brought us together to his office to suggest that we collaborate on publishing the 10 years of work we each had been conducting. That was the beginning of the great adventure that led to the book. Catherine (Tappy) Lynn Plate 8

edited the book with us over summer months, and we also launched an accompanying exhibition of the book’s 27 drawings that traveled to museums and libraries across Florida. A few of the drawings are at the top of Glasgow Hall today (Joanna Lombard).

Florida’s historic gardens and landscapes are the subject of a new book and traveling exhibition. Historic Landscapes of Florida by Rocco J. Ceo and Joanna Lombard details the history and design of 27 such diverse landscapes as Miami’s Villa Vizcaya and Parrot Jungle; the Fairchild Tropical Gardens in Coral Gables; Sarasota’s Ca’ d’Zan; the Mountain Lake Sanctuary (Bok Tower Gardens) in Lake Wales; and the Ravine Gardens in Palatka. The volume is richly illustrated with handsome line drawings, historic postcards and views, and contemporary photographs. Thirty original drawings from the book will be on display at the Thomas Edison Estate and Botanical Gardens in Fort Myers March 1 to May 31 and at the Mennella Museum of American Folk Art in Orlando October 1 to December 31. The book and accompanying exhibit were made possible by a grant from the Deering Foundation.31

31 “A New Look at Florida’s Historic Landscapes,” Florida History & The Arts Magazine 10, no. 2 (Spring 2002): 5.

Place Making: Developing Town Centers, Main Streets, and Urban Villages. Urban Land Institute, 2002

Brief Description

Place Making was the first book to specifically focus on New Urbanist town centers. The book was commissioned and published by the Urban Land Institute, the oldest and largest network of cross-disciplinary real estate and land use experts in the world. Place Making remains in print today and has been a best-selling book in the extensive ULI catalog for over two decades.

Publisher’s Description

Addressing one of the hottest trends in real estate—the development of town centers and urban villages with mixed uses in pedestrian-friendly settings— this book will help navigate through the unique design and development issues and reveal how to make all elements work together.

Author’s Comments

The creation of Place Making was a pivotal moment in my personal life and career, almost like a Dickens story. I was all but dissertation at UNC-Chapel Hill and spent the summer writing three grant proposals to fund my doctoral research, “The Social, Civic and Symbolic Functions of the Public Realm: A Comparative Analysis of New Urbanist Town Centers and Conventional Shopping Centers.” I had turned down opportunities to explore different topics and use existing data from faculty research grants I was involved in, taking a risk that I might persuade someone to fund my research on New Urbanism. That fall, the anxiety grew around the dinner table as rejection letters arrived one after another (picture the family by the fireside with three children aged 7 months to 5 years). I was writing book reviews for Urban Land at the time, and a friend suggested I propose covering a ULI conference on town centers and writing a feature article to help advance my research. That proposal was approved but quickly canceled because the assignment had already been promised to another writer. Just a few weeks later, I received a call from a vice president at ULI, who had read my letter about my dissertation research on town centers and asked me to submit a proposal for a book. The project was approved on Thanksgiving Day, securing the funding I needed to visit the case study sites and meet with dozens of developers, architects, consultants, and local officials involved in the projects featured in the book and, later, in my dissertation.

The writing of the book began in Chapel Hill and continued in Miami less than a year later, when I joined the faculty at the School of Architecture. While most ULI books

focus primarily on contemporary case studies, my proposal called for additional chapters on “Learning from the Past,” “Timeless Design Principles,” and a “Compendium of Placemaking Practices for Town Centers” as a concluding chapter. The goal was to give the book a longer shelf life, which has been born out over the years, and I credit the rich intellectual environment and engagement of my colleagues at the School of Architecture as being instrumental in helping me realize that goal (Chuck Bohl).

Ever try to create a mixed-use development? Do not try it without first reading Place Making: Developing Town Centers, Main Streets and Urban Villages by Charles C. Bohl. This excellently researched book describes the state of the art of mixed-use, placecreating developments. The case studies are particularly valuable ... The book seamlessly serves a variety of audiences: developers, planners, designers, and general readers interested in urban places (Douglas Farr).32

32 “Urban Design,” Journal of the American Planning Association 70, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 103-04.

Florida Modern: Residential Architecture 1945-1970. Rizzoli, 2004

Publisher’s Description

Between 1941 and 1966, Florida became host to sweeping innovations in residential architecture rivaled only by what was happening in California with the Case Study Houses. Florida Modern documents the best work of the era, from Key West to Jacksonville, documenting numerous unsung and unpublished masterpieces by such architects as Paul Rudolph, Gene Leedy, and Rufus Nims. With today’s widespread resurgence of interest in “Mid-century Modernism,” the houses appear as fresh and contemporary as they did over 50 years ago. Many of the houses have been preserved as they were originally built, with Saarinen chairs and Eames furniture all part of the mise-en-scène.

While these houses found their inspiration in part from the philosophies of the Bauhaus, they were quick to incorporate aspects of regional Southern architecture, using verandas, porches, and raised floors to open out to tropical vegetation, and more importantly, cooling breezes. The appeal of many of these homes is the blurring of indoors and outdoors, the connection to the natural environment, and, perhaps even more so today, the ecoconscious spirit that favored local materials and natural ventilation.

Author’s Comments

I had the good fortune to be mentored by one of the Sarasota School’s leading figures, Mark Hampton. Through that relationship I was given the opportunity to photograph not only his work, but also the architecture of Carl Abbott, Paul Rudolph, Gene Leedy, Victor Lundy, and other luminaries. Much of their most significant work was completed before I began my own career, so revisiting these projects was both a privilege and a challenge. Documenting this body of architecture allowed me to engage directly with a vital chapter in Florida’s modernist history, and to contribute to preserving its legacy for future generations (Steven Brooke).

Florida’s fragile, elegant early Modern architecture has been comparatively uncelebrated, even in a period of intense interest in the decades immediately following World War II. The notable exception was, of course, Paul Rudolph, who lived in Sarasota in 1940 and 1941 and returned after the war to produce works of enormous delicacy and delight before leaving in 1958 to become dean of architecture

at Yale. The Sarasota School (as it came to be called) eclipsed inquiries into other postwar architecture in Florida.

Jan Hochstim’s Florida Modern, with a fine selection of contemporary photographs by Steven Brooke, goes far to redress the oversight. Hochstim, a professor at the University of Miami School of Architecture, notes that the postwar Florida house did not necessarily “reflect the prewar European concern for social significance and functionality,” but rather, it was based on a fierce desire to experiment with materials and forms responsive to a hot and unyielding climate. Thus came houses with deep, overhanging flat roofs, louvered windows, and cross ventilation. Before air-conditioning became the norm, houses were wrapped around courtyards or ensconced within a larger screened enclosure, as in Igor Polevitsky’s 1949 Birdcage House.

These houses are finally getting their due. Many that survived have owners committed to preserving them. Hochstim has documented almost 100 houses in his statewide study, which is enhanced by informative text and an appealing design, itself an ode to the graphics of the era (Beth Dunlop).33

33 “Florida Modern: Residential Architecture 1945-1970.” Architectural Record 194, no. 4 (April 1, 2006): 70.

34 “Great Houses of Florida Book Celebrates Legacy of Florida’s ‘Great Houses’.” Sarasota Herald Tribune, 25 Oct. 2008.

Great Houses of Florida. Rizzoli, 2008

Great Houses of Florida, published by Rizzoli in 2008, is a lavishly illustrated book that provides a tour of some of the state’s most notable and intriguing historic homes. The book showcases a variety of architectural styles and periods, including iconic residences such as the Ca’ d’Zan, the Venetian style palazzo of John and Mabel Ringling in Sarasota; Villa Vizcaya, James Deering’s spectacular Italianate estate in Miami; and the historic homes of Ernest Hemingway and John James Audubon in Key West. Featuring new color photography, the book offers a detailed look into the architecture and history of these magnificent houses, which were once the winter playgrounds for America’s wealthiest and most famous figures.

Collaboration is always the key! I was a “Florida Humanities Road Scholar” giving talks on the Historic Landscapes of Florida work all over the state. As I encountered historic properties and communities seeking to preserve them, Beth Dunlop suggested that telling the stories of the houses associated with the landscapes would contribute to those efforts. The editors at Rizzoli had done another kind of “Great Houses” book so they provided support. We connected with Steven Brooke, who set out on a photographic journey and the book came together over many months of exploration and research. Then we traveled around Florida to give talks at many of the houses, and they shared their stories of the book bringing attention to their preservation efforts, which was an especially rewarding aspect of the project (Joanna Lombard).

Vizcaya, El Jardin, Ca’ d’Zan. These are among the landmark houses of Florida, celebrated in a new book from Rizzoli New York, “Great Houses of Florida,” by Beth Dunlop and Joanna Lombard, with photography by Steven Brooke.