20 minute read

The Life of David Bailly

All accounts of the life of David Bailly draw on the same source, art historian Josua Bruyn concluded in the first major review paper on the artist, written in 1951: town historian Jan Jansz. Orlers’ short biography of his fellow Leiden resident published in his Beschrijvinge van Leyden (1641). The one-and-a-half pages that Orlers devoted to Bailly’s life remained an important point of departure for all later studies on the painter. Orlers undoubtedly obtained his information at first hand, as Bailly was ‘to this day practising his Art to great acclaim’ when the book was published. Orlers’ admiration of his work was no mere lip service: an inventory of the contents of Orlers’ home included portraits of his daughter Barbara and her husband painted by Bailly (fig. 2) 1 Bruyn and other later authors showed that there were many other details to be added to Orlers’ concise biography. Though much remains unclear about the life of the painter, this article – based on systematic archive research – provides the basis for a new biography.

An academic environment

Advertisement

David Bailly was probably born in 1584, the fourth child of Pieter Bailly from Antwerp and Willempgen Wolfertsdr. of Noordwijk. His parents had married in Leiden in 1577, and had a daughter Anna, followed by a son Anthonij and a second daughter Neeltgen. After the birth of David the couple had another daughter, Susanna, and possibly also a sixth child.2 In 1581 the family rented a house on Steenschuur with Pieter’s sister Jacquemijne, her two children and a boarder.3

Pieter Bailly was one of many Protestant immigrants who sought refuge in the northern Netherlands.4 Most quickly established themselves in society, and Pieter was no exception. He started working as an engraver and calligrapher for the newly established university (1575) and town council. In 1582 he took a position as handwriting teacher to ‘all students and citizens’ children’, at an annual salary of 72 guilders, a monthly allowance of eight stuyvers per pupil, and free accommodation in Faliede Bagijnhof.5

In 1586 Pieter engraved his Nouvel alphabeth, a calligraphic instruction booklet for school teachers and pupils, the first edition of which he published himself, with subsequent editions issued by an Amsterdam publisher.6

It was there, literally at the heart of Leiden’s academic world, that David was born, next door to the former church that housed not only the university library, but also an anatomy theatre and a fencing school. Diagonally opposite the house where he was born, on the other side of Rapenburg, was the Academy Building, and behind that was the botanical garden (1590). The family moved when Pieter became the academy’s second beadle in 1590 – the Flemish immigrant Louis Elsevier remained first beadle – and was allocated a house on Achtergracht, near

Nonnensteeg.7 In 1594 the Baillys returned to Bagijnhof, where a new fencing school had just opened, and Pieter went to work as a fencing teacher.8 He also retained his position as beadle at the academy, and worked as a calligrapher for the office of the town clerk.9 In 1594 and 1595, for example, he was commissioned by town clerk Jan van Hout to make a fair copy of the first parts of all borough rights and privileges. When Prince Maurice was ceremonially welcomed to Leiden in 1594, Pieter applied the inscription to the triumphal arch that was erected on Kort Rapenburg, and three years later he was responsible for the gilt inscription on the new façade of the town hall.10 In May 1595 he received permission to install windows in the roof of his loft to provide enough light for the

‘constpersse’ (plate press) which he needed for his work for François van Ravelingen’s academic printing press. He was also granted permission to open a shop in the gateway of the Academy building – probably selling prints and study materials – on condition that no women would be admitted.11

Training

This environment was crucial for David’s personal and professional development. He grew up in the middle of town, with a father who worked for the university, and had firm roots among Leiden’s craftsmen, artists and Calvinists. As a ‘Constig Schrijver’ (literally an ‘artistic writer’) – in the words of Orlers – Pieter allowed his son to practise first with a pen, and then entrusted him to the tutelage of engraver Jacques de Gheyn II, who lived in Leiden between 1596 and 1602. Bailly was taught to paint by surgeon and painter Adriaen van der Burgh.12 He will have encountered numerous Dutch and foreign students and professors in his father’s shop every day, and the fencing school was also a favoured place for well-to-do young men to meet, as a 1610 print clearly shows (fig. 3)

The fencing school was run by German mathematician Ludolph van Ceulen. In June 1594 he had received permission from the town council to equip a room above the library at the former Faliede Bagijnkerk church for the school.13 It is not clear precisely what duties Pieters had as his assistant; according to his contract, he was not allowed to give lessons independently. After he was discharged from his position as beadle in 1598, and following repeated complaints that Pieter had no regard for the provisions of his contract, in 1602 the Leiden magistrate banned him from working as a fencing teacher.14 This was undoubtedly one of the reasons behind his relocation to Amsterdam a year later. His wife had died in the meantime, and his three oldest children were grown up. In May 1603 ‘Pieter Baillij, fencing master’, rented a house from the St Pietersgasthuis in Amsterdam for eighty guilders a year, and a year later he became betrothed to Catelijne de Witte of Leeuwarden.15 The couple had four children between 1603 and 1608.16

Amsterdam – and beyond

It is possible that David moved to Amsterdam with his father, though Orlers states that he had become apprenticed there to painter and art dealer Cornelis van der Voort, an immigrant from Turnhout in Flanders, in 1601.17 Unfortunately, we know nothing more about David’s years in Amsterdam. Did he perhaps help his father with his illustrations for his fencing manual Cort Bewys van ‘t Rapier alleen, which the ‘appointed Fencing Master of Amstelredam’ presented to Maurice of Nassau? The album, containing 23 separate ink and watercolour drawings showing the correct positions for fencing, included in the titles and short descriptions a sample of all forms of

lettering that Pieter was able to offer as a calligrapher (fig. 4)

The Cort Bewys was part of a tradition of books on weapons and fencing dedicated to Maurice, who was very interested in military matters – including the Wapenhandelinghe (1608) by David’s early mentor Jacques de Gheyn II, on which Pieter’s book was probably based.18 The manuscript was Pieter’s final achievement; he is believed to have died in 1608 or 1609.19

Was this why David embarked on a long trip around that time? Orlers states that he developed a ‘desire and appetite’ to discover other countries and artists, and in the winter of 1608 he left for Hamburg, where he would spend a year. There is no known evidence of what he did there, but it is likely that he sought out distant relatives or merchants from the Flemish immigrant community for whom he may have worked on an ad hoc basis.20 In 1609 David travelled south, along the usual trade route via Bremen, Frankfurt, Augsburg and Tyrol to Venice and, eventually, Rome.21 According to Orlers, he intended to spend a few years there, but for reasons that are unclear he quickly returned to Venice, where he lived for a few months in 1610. Although there is also no evidence relating to his time in Venice, it again seems likely that David would have contacted other Dutch residents of the city, either merchants or artists.22 Who he met, what he saw, and what artistic influence this had on him remains uncertain, unfortunately.23

Bailly must have embarked on his return trip to the Dutch Republic around 1611. He travelled north along the same route, with stops at various German courts where, according to Orlers, he ‘practised his Art at the homes of divers great Gentlemen’. Orlers names some of them, including Simon VI Count of Lippe-Detmold, Count Ernst zu Holstein-Schaumburg in Bückeburg, and Anton II von Oldenburg-Delmenhorst or Anton Günther, Count of Oldenburg, all art lovers and enthusiastic builders. His greatest admirer was Henry Julius, Duke of BrunswickLüneburg, who was so convinced of David’s talents that he offered him a permanent position, which the painter ‘politely’ declined.24 If Orlers’ account is correct, this means that the duke had seen Bailly’s work. He may have been the anonymous ‘Mahler’ (painter) who portrayed Henry Julius’ younger sons in 1611, for which he received the sum of ten Reichsthaler 25 But no evidence of any other commissions or work from this period of Bailly’s life has been found.

Back in Leiden

David Bailly arrived back in Leiden in the course of 1613. Once there, he could rely on a familiar family network. His brother Anthonij and sisters Neeltgen and Susanna had married local partners, and their children also lived in Leiden. Only his eldest sister Anna had left Leiden, moving to Delft in 1607, after marrying spectacle and lens maker Evert Harmansz. (van) Steenwijck.26 David’s aunt

Jacquemijne had married a member of an old Leiden family, Symon Thomas van Swieten, secretary of the board of orphanages, around 1590 (before David moved to Amsterdam). Van Swieten had died in the meantime. Their daughter Maria married the painter Aernout Elsevier in 1607; he was the son of Louis, her uncle Pieter Bailly’s former colleague in his role as beadle. Together, they ran De Gekroonde Regenboog inn on Breestraat, which was frequented by Bailly and other Leiden painters.27 Maria’s sister Jacomijntje married Aernout’s cousin Isaac Elsevier in 1616. The Elsevier and Bailly-Van Swieten families were therefore doubly related, and notarised documents from the time show that members of the family regularly witnessed legal or business transactions for each other.28

The earliest known painting by Bailly dates from 1616. That was the year he took on Niclaes Adriaenssen as his student. Adriaenssen, a boy from Antwerp, moved to Leiden with his mother in 1611. He had first been taught by Paul van Somer, who lived at De Roode Leeuw inn on Breestraat, owned by Steven de Gheyn (brother of the engraver). When Van Somer left Leiden Bailly, ‘a very good expert master’, was brought in to replace him.29 Bailly was not impressed with his pupils (and nephews) Harmen and Pieter Steenwijck. He had taught them for five and three years respectively, but according to his housekeeper complained that the boys ‘did little work’ and that he had received no reimbursement for costs, board and teaching.30 Another Leiden apprentice was Willem van Heemskerck. His name appears in a 1622 account of an argument involving Bailly which got out of hand. The affair shows that he was actively involved in the art trade, working with fellow Leiden painters including Aernout Elsevier and Cornelis Liefrinck.

On Monday 7 March 1622 Michiel Chimaer, an auctioneer at the boedelkamer (which sold the effects of deceased persons), appeared in the ‘Voorcamer’ (antechamber) of the space that Bailly rented at the home of tailor Isaac de Coene, on Kloksteeg. Van Heemskerck, who had been painting there, stated that he had seen nothing, but had heard Bailly and Chimaer talking about a receipt, and that there was a lot of cursing, and striking ‘with fists’. Bailly’s landlord stated that he heard ‘a din and stamping of feet’ upstairs and went to see what was happening. He had not seen any fighting, though he did witness some ‘squabbling’. He believed the argument had arisen when Chimaer refused to write a receipt for fifteen guilders that Bailly had paid for paintings. ‘Why should I give you a receipt when you have not paid?’, Chimaer had responded in a mocking tone. Bailly grasped him firmly by the arm and said he would not let him go until he gave him proof of payment. Chimaer then admitted he had received the money, but threatened on leaving the room that he would seek retribution.31 Chimaer did indeed take Bailly to court for causing injury to a public person in the performance of their duties. According to his version of events, the deadline for payment for the paintings had long passed, he had issued Bailly several reminders, and had now come to collect the money himself. The painter immediately cursed him, calling him a ‘filthy knave and worse’, though he did pay him the money. Bailly was however so impatient as Chimaer looked for his change that he hit him ‘harshly’ on the head five or six times. This sequence of events had shocked Chimaer so much that he was unable to write out a receipt. The bailiff viewed the matter very gravely, and ordered Bailly to be given a public reprimand, fined three hundred guilders and banned from the town for four years. This did not come to pass, possibly because of the exculpatory statements made by his pupil and landlord.32 He did not even lose his position in the civic guard.33

The unspecified paintings that Bailly had bought from Chimaer came from the collection of François Boudewijns, an eminent merchant from Den Bosch who for many years had lived in Staden near Hamburg, and in 1609 acquired poorterrecht (‘citizens’ rights’) in Leiden. After Boudewijn’s widow Jacquelijne Chombaerts died in 1621 an inventory was drawn up at a vacant premises on Rapenburg belonging to Bailly’s cousin by marriage Aernout Elsevier, where her effects were auctioned off.34 Bailly bought the paintings on behalf of François Schuyrman, Chombaerts’ grandson from her first marriage. His brother Abraham Schuyrman engaged the painters Cornelis Liefrinck and Elsevier to bid on work at the same auction. François Schuyrman handed over the formal written request for these services in the presence of Bailly, who stated that Elsevier and Liefrinck were paid ‘a double rider’ for their services, a considerable sum (28 guilders). The idea was to drive up the price for the ‘picture of the crucifixion of our lord opening with two doors’ (presumably an altarpiece), in order ‘also to benefit’ the auction house. They were authorised to bid up to 1500 guilders. Bailly played it safe: he stated that he could no longer recollect whether he had heard of this plan before or after the auction.35

Established art dealer and painter

Bailly’s status in the art world in Leiden meant he was often engaged to value artworks.36 He traded art with other members of the Leiden painters’ guild, including pieces by Esaias van de Velde II, Quirijn Ponsz. van Slingelandt and Maerten Fransz. van der Hulst.37 As co-founder of the guild, Bailly co-authored its first set of rules pertaining to the sale of paintings (‘Ordonnantie op het vercopen van Schilderijen’, 1642), designed to curb competition on the town’s art market.38 His fellow dealers and artists appreciated his expertise, and in 1645 Bailly and three others were nominated to run the guild.39 Nothing came of the nomination, though in 1648 he was indeed appointed head of the guild, and dean thereafter.40

Alongside his activities as an art dealer, Bailly was first and foremost a portrait painter. He lived close to the Academy Building, as he had during childhood, and had clients within the academic community, including a number of professors, and also well-heeled foreign students such as the Polish Prince Janusz Radziwiłł, Bohemian nobleman Samuel Grudna-Grudzinsky and Christian Rosenkrantz of Denmark.41 His portraits of professors were published mainly as prints, and Bailly had a preference for engraver Willem Jacobsz. Delff.42

Like his father, David like to move in intellectual academic circles, as evidenced for example by his drawing in the album amicorum of his ‘great’ friend Cornelis de Glarges.43 Another contributor to this album was Gérard Thibault, who had connections with the interests, associates and networks of both Bailly and his father (fig. 5)

Born in Antwerp, Thibault had become one of the most innovative fencing masters in Europe, favoured by Maurice of Nassau and other princes. In 1622 he moved to Leiden, where he and the Elseviers started work on a grand publication about the art of fencing, the Academie de l’espée (1628-1630). The title page features an engraved portrait of the author, made after a 1627 design drawing by Bailly.44

Marriage and death

Bailly married in 1642, at the age of 58. His new wife, 15 years his junior, was Agneta van Swanenburg. She was the only as yet unmarried daughter of Maertgen Gerritsdr. and Leiden notary Cornelis Pouwelsz. van Swanenburg.45 Her sisters Trijntgen (Geertruut) and Heyltgen (Helena) had both married much earlier.46 Agneta’s parents were fairly well off. They owned houses around Garenmarkt, bought several grave plots at St Peter’s Church and had purchased annuities for their five children.47 In 1632 her mother – a widow for some years by then – decided that Agneta, as an unmarried woman, also had the right to the 4500 guilders that her sisters had received when they married.48 Why Agneta did not marry until she was in her forties is unclear.

Agneta and David did not have children, and in their wills (drawn up in 1644 and 1657) they left virtually all their assets to each other. Little is known about their marriage, apart from a number of official documents pertaining to business matters: the management of an avenue with a ditch alongside it from Agneta’s father’s estate, the sale of a bond, a loan.49 In financial terms, the relationship between Bailly and his in-laws was somewhat unequal. The will of the wealthy Leiden goldsmith Jan van Griecken and his wife Helena (Heyltgen) van Swanenburg bequeathed Agneta – in the event that all three of the couple’s daughters and their children were deceased – a half-yearly endowment of 250 guilders. Upon Agneta’s death, however, this would not be transferred to David.50 His assets worth 5000 guilders (in 1646) had come almost entirely from his wife, who is also explicitly named in tax records.51 They never bought a house, but lived instead in David’s rented rooms on Kloksteeg. Nevertheless, their assets shrank considerably over time.52 Barely five months before his death Bailly, a devout Calvinist, became cellar master at the Staten Collegie theological college, presumably perhaps to earn a little extra income.53

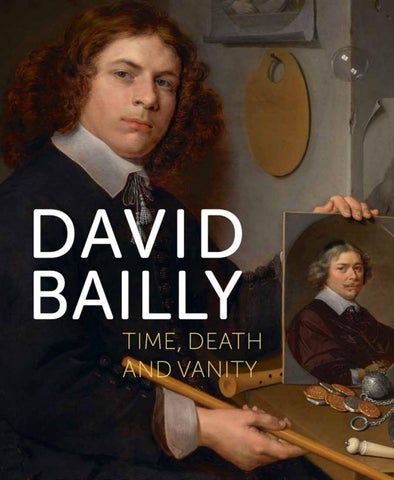

On 5 November 1657 a grave was opened at St Peter’s Church for ‘Mr Davidt Ballij’, undoubtedly the plot that Agneta had been given by her mother, near the southern wall of the church.54 Bailly had always had a view of that wall when he was working in his ‘voorcamer’. It was his view when he made his great Vanitas Still Life with Portrait of a Young Painter. Life and death were always close – both literally and metaphorically.

1 Orlers 1641, pp. 371-372. Estate Inventory: ELO, Weeskamer (Board of orphanages), inv. 13479, fol. 5v (1640).

2 The children at ELO, SAII Census, inv. 1289, fols. 23r-v (Sept. 1581). Pieter later stated that he had six children. During the same period, several immigrants named Bailly (and variant spellings) lived in Leiden. They included a David Bailly, tanner; an Anthoni and a Susanna, all members of the Wallonian Church. They do not appear to have been related to the painter.

3 ELO, DTB Ondertrouwboeken (Register of banns of marriage), inv. 1A, fol. 60v (28-12-1577); ibidem, ORA Waarboeken (Register of property transactions), inv. 67H, fol. 291r (15-1581) residing at Hooigracht; Census 1581 (n.2): Steenschuur.

4 I have been unable to unearth any information about the time Pieter spent in Antwerp. Bailly is a common name among Flemish immigrants, with families in Amsterdam, Hamburg and elsewhere.

5 ELO, SA II Gerechtsdagboeken (Court records), inv. 45, fol. 151v (22-2-1582); Molhuysen 1913, p. 33 (28-4-1582). For the address, see also the tax records for 1583 and 1585: ELO, SAII Vetus 1585 and Omslag 1583.

6 A unique copy at Columbia University Library, New York.

7 Witkam 1971, p. 70 (26-111590). Appointment as beadle and applications for building alterations: ELO, SA II Gerechtsdagboeken (Court records), inv. 46, fol. 49r (3-11591); ibidem, fols. 67v-68r (21-21591); ibidem, fol. 83v (4-4-1591).

8 Witkam 1971, p. 71 with sources.

9 ELO, SA II Gerechtsdagboeken (Court records), inv. 44, fol. 459v (21-8-1586): request for exemption from civic guard duty in connection with appointment to position in office of town clerk.

10 Rammelman Elsevier 1857, p. 283. Bill (32 guilders) in Pieter’s handwriting: ELO, SAII Bill copy, inv. 795, no page no. (undat.). Overvoorde 1908, p. 19: bill from Bailly for 26 guilders for gilt inscriptions on town hall (17-8-1597).

11 Molhuysen 1913, p. 93 (24-5-1595).

12 Orlers 1641, p. 371. Adriaen van der Burgh’s wife was De Gheyn’s sister.

13 ELO, SA II Gerechtsdagboeken (Court records), inv. 47, fol. 50r (6-9-1594). On Van Ceulen, see Rammelman Elsevier 1846.

14 ELO, SA II Gerechtsdagboeken (Court records), inv. 47, fols. 266v-267v (25-1-1602).

15 SAA, Gasthuizen (Shelters for indigents), inv. 1454 (25-5-1603); ibidem, Trouwboeken (Marriage register), fol. 225r (20-5-1604); NHA, Ondertrouwboeken (Register of banns of marriage), inv. 47, p. 261 (23-5-1604).

16 SAA, DTB, inv. 4, p. 99 (Pieter, 198-1604); inv. 39, p. 78 (Annetje, 25-10-1605), p. 114 (Marij, 4-2-1607) and p. 161 (Herman, 26-8-1608). Pieter Sr. was still alive in August 1608.

17 Orlers 1641, p. 371. Thomas de Keyser was also a student of Van der Voort.

18 The Hague, National Library (KB), sign. 72 F 37. Galas/ Steenput 2011.

19 In 1608 Cornelis van Heusden succeeded him as fencing master: Fontaine Verwey 1978, p. 290.

20 Hamburg, Staatsarchiv, Stade Reformed Church, inv. 111-1 nr. 87194 (baptism register): listings for Anthoine, Estienne, Anna and Hans Bailly (1591-1592); idem, inv. AI2 (Niederländische Armenkasse).

21 Was this trip connected with the unspecified conflict between Bailly and a merchant from Bremen? ELO, ORA Schepenbank (Aldermen’s court), inv. 47N, fol. 242r (19-8-1622).

22 Research in Venice at the Archivio di Stato Veneziana and at the Archivio di Storico del Patriarcato di Venezia, Archivio segreto (Status animarum) has yielded no results so far.

23 The St. Sebastian figure in Bailly’s still lifes may have been inspired by the statue by Alessandro Vittoria at San. Francesco della Vigna in Venice: Popper-Voskuil 1973, p. 73, n. 38.

24 Orlers 1641, p. 371. These aristocrats are all known as patrons of architects and artists. Research in their archives (including financial records) in Detmold, Bückeburg and Oldenburg has not revealed any information concerning commissions awarded to Bailly or purchases of his work.

25 Hanover, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv (NLA), Hann. 76c, (Kammerrechnung 1611-1612), A Nr. 42, fol. 132v (Ausgaben auff die Junge Herren vndt Frewlein): ‘nr. 15. Item S.F.S zubehueff eines Mahlers so s.f.s. ab conterfeijt 10 Rthaler = 21-10-0’. The prince portrayed was either Christian or Rudolph. RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, Hofstede de Groot fiches, no. 1013926: listing of a portrait drawing of Duke Christian by David Bailly, auctioned in Amsterdam on 26 November 1792. The wheareabouts of this drawing are unknown. See also Bruyn 1951, p. 153.

26 Zuidervaart/Rijks 2015. ELO, DTB Ondertrouwboeken (Register of banns of marriage), inv. 6F, fol. 11r: wedding of Anna Bailly and Evert Harmansz. van Steenwijck, 23-5-1627); ibidem, inv. 4, fol. 168v: Anthonij Bailly, baker, and Grietgen Pietersdr. van Stralen, 19-4-1602). Neeltgen married I. Job Lenaertsz. of Utrecht, mentioned in ibidem, inv. 8, fol. 258v, marriage to II. Claes Claesz. van Bugersma, tinsmith (10-1-1619) and III. ibidem, inv. 11, fol. 212r to Cornelis van Hemert, saddler (9-6-1636). Susanna was married to Henrick Cornelisz., draper (ELO, NA, inv. 213, doc. 131, 20-10-1627). Jacquemijne Bailly and Symon van Swieten as married couple: ELO, DTB Ondertrouwboeken (Register of banns of marriage), inv. 3C, fol. 120r (13-5-1595). Maria van Swieten and Aernout Elsevier: ibidem, inv. 6, fol. 126 (9-2-1607): their daughter married painter Aernout Waelpot in 1639. Their son Louis also became a painter: Bredius 1915-1922, p. 2133. Jacomijntje van Swieten married Isaac Elsevier on 20-1-1616 (ELO, DTB Ondertrouwboeken (Register of banns of marriage), inv. 8H, fol. 95v).

27 Drinking debts mentioned in ELO, NA, inv. 319, doc. 127 (24-121626).

28 E.g. ELO, NA, inv. 90, fols. 18r-19v (27-3-1609): bond belonging to Jacquemijne Bailly and son-in-law Aernout Elsevier. Idem, inv. 178, fol. 151r (25-41616): Bailly as guarantor for his brother Anthonij, with witnesses Aernout and Abraham Elsevier and ibidem, inv. 236, doc. 148 (1-6-1621): authorisation issued by Bailly.

29 Spiessens 2011, p. 175 (15-4-1616).

30 ELO, NA, inv. 674, doc. 90 (21-4-1660).

31 ELO, NA, inv. 139, doc. 61 (16-31622, statement by De Coene); ibidem, doc. 79 (Willem van Heemskerck).

32 ELO, ORA Correctieboeken (Records of penalties), inv. 4, fols. 149v-151v (12-3-1622).

33 In 1626 Bailly received three guilders for efforts with regard to items for the civic guard: ELO, SAII Schutterij, inv. 5, fol. 213v (7-3-1626). In June he asked to be discharged from the civic guard because he wished to move house. Permission was not granted: Bruyn 1951, p. 154. In 1628 ‘officer’ Bailly made a statement concerning a bill of exchange from Danish students: ELO, NA, inv. 365, doc. 9 (30-5-1628).

34 See Rapenburg VI, pp. 88-89. Estate: ELO, NA, inv. 101, doc. 84 (6-7-1621).

35 Six years later, all concerned gave evidence at the request of François Schuyrmans: ELO, ORA Getuignisboeken (Witness statements), inv. 79, fol. 176r (Bailly, 1-4-1627); fol. 185r-186r (Elsevier, 30-4-1627) and fol. 208r (Liefrinck and Bailly on the artwork and the efforts to drive up the price, 22-9-1627). The painting was in the ‘camer: 1 schilderije met dooren van de passie’ (‘1 painting of the passion with doors’), presumably an altarpiece: Rapenburg VI, p. 125. A piece on which Bailly, ‘aged approximately 40’, gave evidence concerning a valuation may also be this work: ELO, NA, inv. 248 (10-3-1627).

36 ELO, SA II Schepenbank (Aldermen’s court), inv. 47Y, no page nos., (6-2-1643).

37 ELO, Gilden (Guilds), inv. 855, no page nos., (1644-1645).

38 ELO, Gilden (Guilds), inv. 849, pp. 3-5 (13-4-1642).

39 ELO, SA II Gerechtsdagboeken (Court records), inv. 66, fols. 92r-93v (4-4-1645). ELO, Gilden (Guilds), inv. 849 (16-6-1644): payment of membership fee.

40 In this capacity Bailly submitted a complaint to the town council with other members of the guild board: ELO, SA II Gerechtsdagboeken (Court records), inv. 66, fol. 93r (18-3-1648), also Gilden (Guilds), inv. 849, pp. 7-8.

41 Radziwiłł: Wroclaw 2006, p. 282; Alb. Stud. col. 234 (14-4-1631). Grundzinsky: ELO, NA, inv. 521, nr 9 (9-11633): acknowledgement of 15-guilder debt to Bailly for work supplied; Alb. Stud. col. 230 (28-9-1630). Rosenkrantz: Alb. Stud. col. 291 (19-11-1637).

42 ELO, ORA Vredemakersboeken (Conciliation records), inv. 47N, fol. 214r (27-6-1622): case of Pieter de Clopper v. Bailly concerning the portrait of Festus Hommius. Bailly had recommended that the portrait ‘be cut’ in Delft, during which process it seems to have been damaged.

43 KB, 75 J 48, fol. 161r.

44 On Thibault: Fontaine Verwey 1978. The design drawing was auctioned by Christie’s London, auction 29-11-1977, lot. 138.

45 ELO, SA II Schepenhuwelijken (Marriage register), inv. 199, fol. 149v (3-5-1642). Witnesses: Bailly’s cousin Simon van Swieten (Aernout Elsevier’s brother-in-law) and Wullemke van Tettrode (Agneta’s aunt).

46 ELO, DTB Ondertrouwboeken (Register of banns of marriage), inv. 1A, fol. 230v (10-11-1584): wedding of Agneta’s parents, both approximately 23 years of age. Their children were Jacop

Cornelis (b. c. 1586), Trijntgen (b. c. 1590), Heyltgen (b. c. 1594) and Agneta (b. c. 1598).

47 Huizen: ELO, SAII Bonboeken (Property register) inv. 6617, fols. 416r and 412v; inv. 6618, fol. 57r. Graves at St Peter’s Church: ELO, Kerkvoogdij grafboeken (Church burial records), inv. 993, fols. 41r and 85v-86r. Annuities: ELO, SA II Tresorie-ordinaris (Town financial records), inv. 7473, fols. 633v and 639r-v; inv. 7477 fols. 481r-v.

48 ELO, NA, inv. 308, doc. 112 (29-12-1632); ibidem, inv. 309, doc. 27 (22-1-1637). Agneta in fact made two wills in which her mother was beneficiary: ibidem, inv. 204, doc. 77 (27-4-1618); inv. 207, doc. 63 (28-8-1621).

49 Concerning the avenue: ELO, NA, inv. 113 (no page nos. 3-9-1642); ELO, ORA Getuignisboeken (Witness statements), inv. 79W, fol. 136r-137v (29-9-1642). Bond: ELO, NA, inv. 447, doc. 62 (243-1654).

50 ELO, NA, inv. 406, doc. 241 (Van Griecken-Van Swanenburg will, 9-9-1652). Her ‘Conterfeitsel’ (portrait) is mentioned in Helena’s estate inventory: ibidem, inv. 762, akte 531. Wills of Bailly: ibidem, inv. 114, doc. 46 (23-8-1644); inv. 845, doc. 34 (18-4-1657). After Bailly’s death Agneta probably rented number 51 Rapenburg: Rapenburg III, p. 716. She made a will in 1666; the estate did not include any paintings: ELO, SAII Schepenbank (Aldermen’s court), inv. 50R, fol. 175r (16-4-1670).

51 They are not mentioned until 1645. ELO, SA II Kohieren vermogensheffing (Wealth tax records), inv. 4356, fol. 74v: ‘Mr David Bailij married to Agneta van Swanenburgh on the assets of his wife ‘ (1646). The assets were worth five thousand guilders.

52 ELO, SA II Kohieren vermogensheffing (Wealth tax records), inv. 4361, fol. 68v: still 3000 guilders in 1654.

53 De Baar 1975.

54 ELO, Kerkvoogdij Blafferd (Church financial records), inv. 157, fol. 7v (5-11-1657); ibidem, Journaal (Journal), inv. 100 (no page nos.). In 1621 Maertgen Gerritsdr. disposed of two burial plots to her daughters in a lottery. Heyltgen won Zuid-buitenwandeling 78 and Agneta Zuid-binnenwandeling 40: ibidem, Grafboeken (Burial records), inv. 993, fols. 41r and 86r.