5 minute read

The Dark Side of Costa Rica

from March 2020

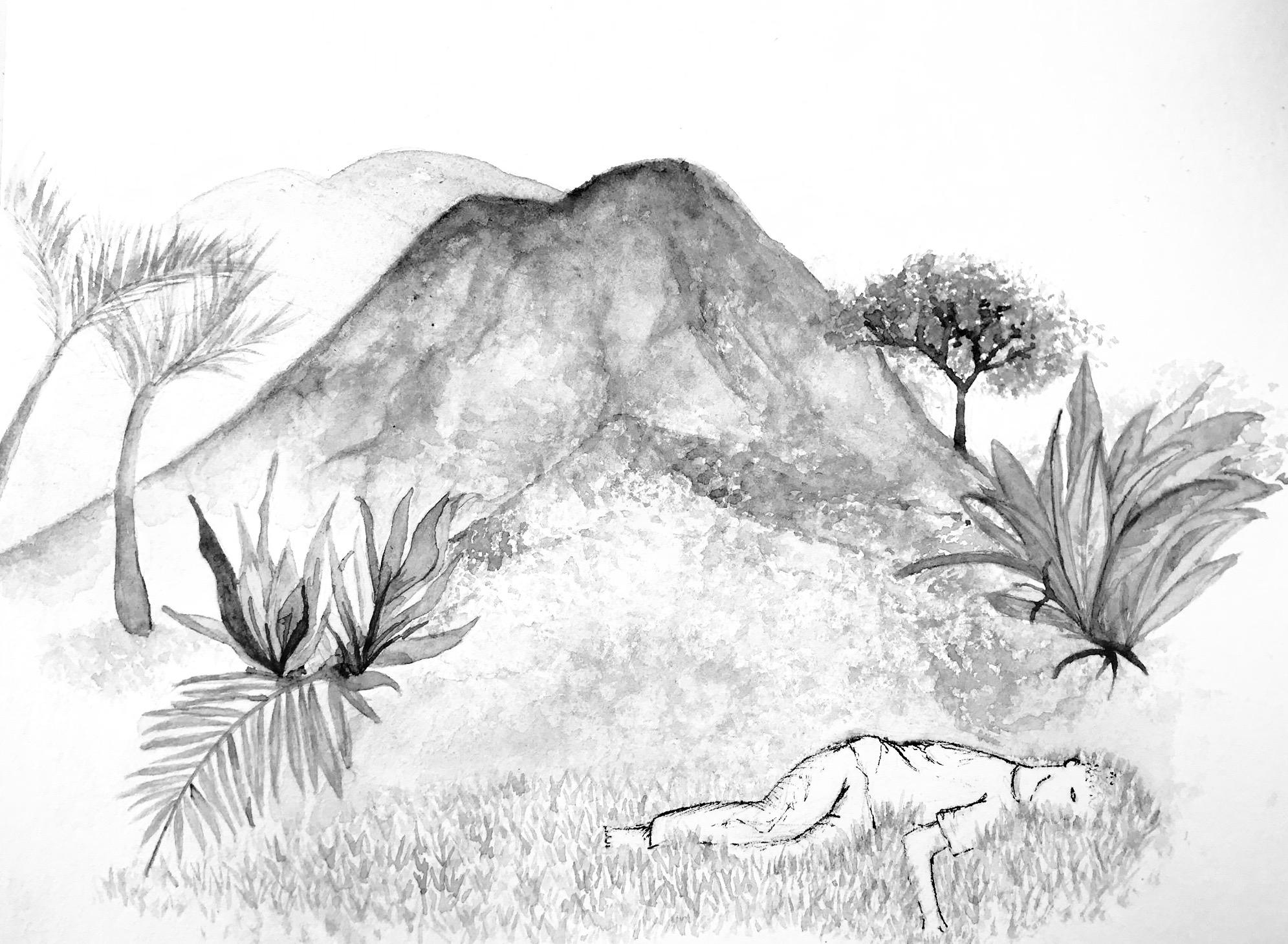

The Dark Side of Costa Rica by Anna Dekker

The prevailing image of Costa Rica is that of a green and peaceful country, making it a popular spot for eco-tourists. Relative to other countries in the area, it is indeed safe and peaceful. As tourism is one of the country’s main sources of income, it is understandable that this image is something the country wishes to uphold. Not surprisingly, most people are not aware of another side of Costa Rica; a side of racism, discrimination and violence. Latin America is seen as the most dangerous continent in the world for people who defend land rights and natural resources, and indigenous communities are often the victims. Costa Rica is not an exception when it comes to this.

Advertisement

On the 24th of February, Jehry Rivera, 45 years old, an indigenous right and land activist who belonged to the indigenous Brörán community in Térraba, was shot and killed by someone in an armed mob. Authorities had been warned before by human rights groups about non-indigenous people violently confronting Brörán families who were trying to reclaim land. According to the National Front of Indigenous Peoples (FRENAPI), two days before the attack, groups of landowners had come to Térraba to intimidate and attack indigenous people participating in territorial recoveries.

The killing of Jehry Rivera does not stand on its own. Two weeks before Rivera was killed, Mainor Ortiz Delgado, 29, a leader of the Bribri indigenous community in the nearby Salitre, was shot in the leg in front of his 13-year-old son. The attacks on Rivera and Mainor Ortiz took place less than a year after Sergio Rojas Ortiz, an internationally well-known land and human rights defender of the Bribri, 59, was shot dead on March 18th, 2019 after having been harassed, assaulted and threatened for years due to his work. Ironically, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights had issued precautionary measures in 2015, urging Costa Rican authorities to protect the lives of the Bribri and Brörán people, and the three indigenous men mentioned previously “received” these safety measures when they were attacked. In addition, to this day, the cases of Mainor Ortiz and Sergio Rojas remain unsolved.

So, what is the context of this violence, and why is it escalating? The eight indigenous ethnic groups in Costa Rica (around 2.4% of the population) were appointed 24 legally recognized indigenous territories in the 1977 Indigenous Act. These territories are exclusively for communities with historical ties to the land. Families who settled on one of these indigenous territories before 1977 are entitled to compensation and relocation by the government, whereas families who settled on these areas after this Act have no right to either. The problem is that this law has never been implemented, so the land was never returned to the indigenous people. Recently, the Bribri and Brörán people have been reclaiming some of their ancestral land through (unauthorized) non-violent occupations, with some success. This has led to tensions, because non-indigenous families and farmers claim their property and inheritance rights are being violated.

The complex situation calls for governmental interference, and many believe that not enough is being done. There is, however, some hope. In March 2018, 24 states approved the first environmental human rights treaty for Latin America and the Caribbean, known as the Escazú Agreement. The treaty aims to ensure access to information, citizen participation and access to justice in environmental matters, and specifically addresses environmental human rights defenders. In Costa Rica, the Legislative Assembly approved the agreement on the 13th of February and it is now awaiting definitive approval. It is a step in the right direction towards better protection of people like Jehry Rivera and Sergio Rojas.

4 Months Later: Smoke and the Coronavirus by Morris Chou

It is a gut wrenching feeling to see a place you called home for 3 years descend into a boiling pot of hate. Black words like “if we burn you burn with us” were easily found accompanying students as they rushed to class. 2019 was a dark year for Hong Kong as the year was dominated by the protest movement that gripped the city. Now, with the Coronavirus, the situation will surely get worse before recovering.

Most recently at a memorial vigil for the university student who died last November,

conflicts between the police and journalists have resulted in The News Executives’ Association and the Hong Kong Journalists’ Association publicly demanding an answer from the government. Carrie Lam and the police later apologized. Nonetheless, tensions still remain high and the city is still divided. It has been observed that some shops refuse to serve “Mandarin speakers” out of fear for the spread of the contagion. Although the dust has settled, smoke is still clearly on the horizon. Hong Kong’s trials are still not over.

Yet beneath the fear and the hate, I found laughter even jokes during the most violent of times last November. When confronting a neighbor about an odd gasoline smell in the bathrooms, it turned out the source of the smell was his attempts at washing tear gas from his clothes. Similarly, there was also fear as he lied about the origins of the scent when confronted for the first time. It was obvious that he did not want me to know he took part in the protest. Nevertheless, it is undeniable to witness the spark and the commitment within the protesters, that they would set aside their comforts and differences to walk on the streets, knowing that clouds of tear gas would shortly greet them.

Although the protest did not achieve the goals it set out, for me it is far from a futile movement led by naïve youths, nor should it be remembered as such. Carrie Lam remained in office and the actions of the police were not investigated. Yet, the people of Hong Kong managed to bring a city of 8 million to a standstill and people halfway around the world are writing articles about it. As they rightfully should.

In the Taiwanese presidential elections that followed the protests closely, it was the Democratic Progressive Party who claimed victory with overwhelming margins under its call for vigilance in guarding the democratic order of the island. The tale of Hong Kong’s protests is far from over and its impacts are far from certain. Therefore, it is with a fearful yet cheerful heart that I hope Hong Kong’s faith in democracy may live on.