42 minute read

The Go-Go Fifties The Distribution Racket; Kinowa, Western Scourge; Charlton’s Pulp

Chapter Ten Rise & Fall of the Action Heroes

CHANGING OF THE GUARD By mid-decade, a new regime was falling into place at Charlton as the publishing outfit was experiencing a generational shift. John Santangelo decided to relinquish some control to oldest son Charles as the company patriarch focused on new business in the old country. And, with Gold Star Books gone bust, Ed Levy was retiring to pursue his hobbies, plus Burt Levey was contemplating going full-time on real estate ventures. While it appeared Masulli assistant Bill Anderson was set to become managing editor of the comics division, Charles Santangelo opted to take a chance on Dick Giordano, who had been begging for the editorial gig. (Anderson eventually led their line of music mags.)

Advertisement

After eight-plus years in the position, Masulli had perhaps grown bored as comics managing editor and, while his term was relatively uneventful, there were a few memorable facets, including the giant monster titles and his enthusiastic shepherding of ill-fated Jungle Tales of Tarzan. Important too was Masulli recognizing that the burgeoning field of comics fandom could be used to Charlton’s benefit by tapping it as a source for talent.

Fanzine editors routinely included publishers on their comp lists and Masulli must have been delighted to read the positive notice regarding Jungle Tales of Tarzan shared by fans of both comics and Edgar Rice Burroughs (though probably less thrilled with comic fans’ seemingly endless criticism of Fraccio and Tallarico’s artwork on “Son of Vulcan” and Blue Beetle). The departing comics editor was also impressed with some of the zines themselves, especially Alter Ego, which, in a missive to editor Roy Thomas, Masulli described as “by far the best printed fanzine that there is.” Still, he was not above griping in blatant self-interest: “Fandom is guilty of being only taste-conscious and not sales-conscious… [though] you people can exert more influence and be of more value to the comics industry.”1 A FAN AT HEART In retrospect, what set apart the Action Heroes line—besides the undeniable quality of Ditko’s artwork—was not only Charlton’s irreverent tone and gumption to cite competitors by name in the letters pages, but there permeated a sense that its guiding hand was, at his core, a comic book fan. And, indeed, Giordano was exactly that, as well as a supremely nice guy endowed with the necessary editorial skills.

When asked by the author what made him believe he was up to the task— jumping from drawing table to editor’s desk—Giordano replied, “I got along with people. I’m sure you know that, Jon. I’m not sure why, it’s not something that I do consciously, but I know that’s the end result, people and I get along, and that I can depend on people to give me a fair degree of whatever skill level they have, just by asking for it. Because I manage things.”2

Giordano shared his simple editorial philosophy with Mike Friedrich. “I try to get the best people working for me,” he explained, “and then let them do their own thing. I figure that writing is the writer’s bag and the same for an artist. I point them in the direction I want to take, of course, and continue to guide them,

Above: Art drawn for a fanzine by Steve Ditko featuring his Action Hero characters. Right: One-page Pat Masulli interview, Comic Feature #3. Next page: Dick Giordano Action Heroes cover, Comic Book Artist #9 [Aug. 2000]. Colors by Tom Ziuko.

but, other than that, I leave them alone. If they produce badly, then they either do it over or stop working for me. That sounds rather harsh—it isn’t as bad as it sounds—the whole thing is a team project, really. It’s just that I believe the major work of writing should be done by the writer, and the artist should be working in his style, not someone else’s.”3

At Charlton, Giordano’s stint as editor, which started in July 1965, was among the finest of a quite august decade in the comics realm, one that boasted at least three top-notch comics editors (whom, incidentally, all had tenures enhanced with the artistry of one Stephen John Ditko). Stan Lee had appropriated the chummy, joking tone of EC Comics and—bolstered by the visionary universe-building and genius storytelling of Jack Kirby and Ditko— transformed Marvel Comics into a cultural juggernaut, morphing into a Baby Boomer icon in the process. Archie Goodwin, as editor and premier writer of the black-&-white comics magazines published by James Warren—Creepy, Eerie, Blazing Combat, and Vampirella—not only resurrected the spirit of EC, but also enlisted a breathtaking array of top-flight artists, including Frank Frazetta, Al Williamson, Neal Adams, and Ditko, who himself was inspired by Goodwin to produce his most bravura artwork.

Of the other two editors, Giordano’s style at Charlton— and as one of DC’s “artist-as-editors”in years that followed —was more akin to much-beloved Goodwin’s editorial approach, that of encouragement and expressed appreciation.

Son of Vulcan

As with the Blue Beetle revival, Son of Vulcan was technically an offspring of the Masulli era—as, after all, the editor co-created the series as its writer—but, while Dick Giordano recalled he was the one to come up with the phrase “Action Hero,” the cover of Mysteries of Unexplored Worlds #46 [May 1965] included the same phrase in a cover blurb. The declaration read that Son of Vulcan was: “The Newest Most Thrilling Action Hero! The Power of the Roman Gods Strikes Again!” (To be fair, that issue, along with the origin of Son of Vulcan, also included a house ad trumpeting “The Greatest Action-Heroes of All Time—On Sale Now,” ad copy that could well have been written under the direction of the burgeoning line’s soon-to-be editor, Giordano.) Despite Masulli answering an emphatic “No!”4 when asked if the character was inspired by a certain “God of Thunder” over at the competition, Son of Vulcan was clearly a swipe of Marvel’s mythology-based “Mighty Thor,” by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, with lame news professional Johnny Mann able to magically transform into a legendary figure (or, at least, an offspring!). After only five issues—the final two renamed for the character—the series ended with the first professional comic book writing by Roy Thomas, a Missouri teacher with quite a future ahead of him.

Son of Vulcan #49 [Nov. 1965] featured a costume redesign submitted by future comics legend Dave Cockrum, who was actually given a cover shout-out on the issue with a “special thanks” for his “costume ideas.”

In later years, despite Giordano’s time as executive editor during arguably DC’s most bountiful creative period —e.g., The Dark Knight Returns and Action Heroes-influenced Watchmen, two projects with which he was intimately involved—Giordano was most recognized for his art, specifically inking. All the same, in acknowledgment of his short but fruitful Charlton era, he was given the Alley Award for “Best Editor” by the Academy of Comic Book Arts and Sciences, in 1969, beating out prior five-time recipient Stan Lee.

Left: Instrumental in helping a good number of artists and writers enter the comics industry, Roy Thomas hoped to see accomplished fan artist Biljo White become a pro with a revival of Son of Vulcan that Thomas intended to write (under the guise of Gary Friedrich). Alas, the Action Heroes era was over by the time this splash penciled by White and inked by Sam Grainger was considered. Above: The cover of Mysteries of Unexplored Worlds #46 [May ’65], a blurb from same, and cover detail of MOUW #47. MOUW covers by Bill Fraccio and Tony Tallarico. “Son of Vulcan” page image courtesy of Aaron Caplan.

STAN LEE’S ASSESSMENT In a 1968 interview with Ron Liberman, editor Stan Lee had these words about the competitors of his Marvel Comics Group: “I don’t like to sound pompous, but we really don’t feel that we have much competition. National [DC], though, is really our only competition now. There are a few good books around, including Magnus [Robot Fighter] and Doctor Solar. Charlton had one or two books with good ideas, but they were battered out so badly, that they didn’t really ever worry us. Charlton has a deservedly bad reputation because their books are very much likes ours were about 30 years ago. All they try to do is bat them out fast; they don’t expect them to sell well, they’re not trying anything. They just turn them out and forget them. For a while, we were like Charlton, except bigger, and we turned out many more books than they did. Eventually we learned that you can’t build a fan following by not having respect for your public and just turning the books out. We learned pretty late in life. It was only six or seven years ago that we realized this.”52

While Giordano’s Action Hero achievements had failed to gain Marvel’s respect, a certain DC Comics “talent scout” had, by the summer of ’67, started to take notice.

HOME OF THE YOUNG In contrast to Lee’s view, some in comics fandom saw Marvel as being in debt to the Derby publisher for introducing a new generation of writers to the business. Glen Johnson opined in a 1970 fanzine, “Of all the companies, Charlton was most similar to Marvel in that they were trying to give each character his own life… and still be different. It must be noted though that Charlton gave people like Roy Thomas, Dennis O’Neil, Steve Skeates, Gary Friedrich, David Kaler, Richard Green, Pat Boyette, and others their first shot in professional writing and/or art. As you will see, most of those are the top names in the young industry today.”53

The New Captain Atom

Dick Giordano reminisced about the overhaul of Charlton’s space-born hero: “I traveled to Charlton’s New York office every Wednesday and met with our New York freelancers, who were delivering and picking up assignments. Besides being a convenient place to distribute checks and accept vouchers for work completed, the weekly meeting also gave me an opportunity to talk comics with the guys on a regular basis. I told [Ditko] of my plans to put together a line of costumed heroes who were not super-powered, as well as the fact that I wanted to keep Captain Atom in the line, even though he was definitely super-powered. Steve said he would try to come up with something that would make the good Captain fit. True to his word, when Steve and I met at a later date, he outlined and later plotted and drew the idea that became [CA #83]… which vastly de-powered Captain Atom and put him at center stage in the Action Hero line… Steve designed a new costume Nightshadefor Captain Atom which was intended, among other things, to call attention to the changes that had occurred in the character. (As an old stick-inthe-mud, I must admit that I liked the old costume better—but necessity called for all-new, and that’s where we went.)”54 Along with the revamping of Captain Atom, Giordano, writer Dave Kaler, and artist Ditko introduced an arch-nemesis, The Ghost, as well as a sidekick—and the first female Action Hero—Nightshade, the “darling of Darkness,” described here by Lou Mougin: “Actually, Nightshade was a refreshing change from the run of the mid’60s heroines. Most distaff super-beings, at that time, deigned to zap villains with [nothing] less ladylike than hex powers or invisible force fields. Charlton’s first-line heroine took the more direct route à la Emma Peel [of the British TV series, The Avengers] and beat the bejeebers out of hardened thugs with her gloved mitts and a little karate. No female was doing that in 1966 comics. After Nightshade, practically all super-heroines took up crash martial-arts courses. She soon won a solo series in the back of Captain Atom for three issues; Jim Aparo’s clean-lined, appealing art made her one of the first well-drawn ’60s solo heroines.”55 This page: Giordano’s overhaul of the atomic man, implemented by Kaler, Ditko, and Mastroserio, culminat ed in Captain Atom #83 [Nov. ’66]; Comic Comments #9 [Nov. ’66] cover by Alan Hutchinson; Captain Atom #84 [Jan. ’67] panel detail, and C.A. #85 [Mar. ’67] cover detail. Captain Atom vignette coloring by Tom Ziuko.

P.A.M. OF THE N.Y.P.D.

Some thought the work was produced by Pat Masulli, as the

Charlton editor, after all, had the same first and last letter in the initials. Others were convinced similarly-styled artist

George Tuska was using a pseudonym while augmenting his

Marvel assignments. And a few recognized the mysterious

PAM’s outstanding artistry had been gracing the pages of

Charlton comics for over a decade by the time the superb Action Heroes series, Thunderbolt, struck the newsstands in late 1965. It took entering retirement from a day job for him to finally reveal his secret in the 1970s, and the artist/writer explained the need for an acronym to Glen D. Johnson in 2000: “Actually, I worked for ten years in comics before the field started to dry up. (No work.) I was married with three kids and looked around for something steady to raise a family on, when someone mentioned that the civil service police exam was coming up. I studied, passed the written Pete Morisi test and the physical, and became a cop. During those days the police department had a ‘moonlighting’ rule about [not] holding outside jobs, and that’s when Charlton called me up and asked me to do one job for them:

‘Please.’ I said, ‘Okay,’ and that one job led to 20 years of work… signed by PAM.”56 Thus Peter Anthony Morisi [1928–2003]—Pete Morisi to most everyone—worked days as dispatcher as a New York City cop and, at night, created comic book stories for Charlton. Between 1955–75, PAM drew and often wrote a number of assignments for the publisher, including a remarkable, if short run of Kid

Montana [#32–39, Dec. ’61–Mar. ’63] involving dinosaurs, apes run amok, and even a Yeti. And he produced innumerable Westerns, among them a marvelous batch of “Gunmaster” adventures between ’64–65. After he left

Thunderbolt—his most acclaimed creation—Morisi went on to produce significant work for the

Derby company into the 1970s, when he proved to be effective on Charlton’s supernatural titles, drawing more than 100 stories.

PAM eventually purchased from

Charlton the rights to his greatest creation, T-Bolt, which, over the years, had been sporadically revived by DC and by Dynamite.

This page: The mysterious P.A.M. was eventually revealed to be Pete Morisi (seen here in his N.Y.P.D. portrait, circa 1956), whose sublime creation, Thunderbolt, is seen here in a cover detail from Thunderbolt #56 [Feb. ’67]. Thunderbolt #1 [Jan. ’66] opening page referencing the other Charlton Action Heroes.

Peter

Cannon… Thunderbolt

Part AmazingMan, part Golden Age Daredevil, and entirely Pete Morisi, Peter Cannon… Thunderbolt was, aside from Ditko’s Blue Beetle, the most highlyacclaimed title of the Dick Giordanoedited Action Heroes line. During a visit to the Charlton building, PAM noted that seven out of ten letters were for him or T-Bolt. And, despite suggestions to make the character more “Marvel-like,” emphasizing human foibles, “The fan mail,” Morisi declared, “likes T-Bolt the way he is (and this includes the most ‘adult’ mail that Charlton has ever gotten).”57 In a letter, PAM explained the origins of the character: “T-Bolt came into being after I bawled out Pat Masulli for not letting me do Blue Beetle. He mentioned there was an opening for a ‘one-shot’ costume hero super-type strip at Charlton. I said, ‘Okay, I’d submit ideas.’ Then came the long process of thinking. How to do a super-hero and not make him super? I knocked myself out thinking and finally came up with an origin for T-Bolt. Then the same process was repeated in figuring out a name, and once again for a costume. I created Tabu, so that T-Bolt would have someone to talk to. Sounds simple as I tell it, but it was work, work, work!”58 During those years as an incognito comic book creator, Morisi at the time explained, “Charlton’s pay is pretty bad… $25 per page… but it’s worth it to me… because it’s not my only source of income… and they leave me alone! No changes, no corrections, no big conferences, etc., etc. A simple discussion on the phone usually settles what Dick has in mind… or what I want to convey.”59 Because of his full-time commitment as a New York City policeman, meeting deadlines was a perennial problem for PAM, so much so that, after drawing eight of T-Bolt’s 11-issue run, he gave up the assignment, only to see it soon cancelled, along with all the other Action Heroes. For a brief spell, PAM drew new adventures of his “Can… Must… Will” hero in the 1980s for DC Comics, though much of that work remains unpublished. In a 1967 fanzine retrospective, future comics writer/publisher Mike Friedrich called PAM’s character the “leading hero at Charlton,” sharing that the creator “has presented a hero with a truly original power—the ability to utilize the normally unused portions of the brain—and gave the character one of the truly unique secret [identities]. How many other heroes literally loathe becoming their costumed selves? Who also wishes he didn’t have the power he possesses?”60

The New Blue Beetle

Certainly the central character in the Charlton Action Hero universe—at the very least a formidable equal to Captain Atom—was the third incarnation of Blue Beetle, a super-hero not unlike a certain amazing Spider-Man. Ted Kord is able to jump on villains from on high, boasts a terrifically designed costume, and is, simply put, an absolutely charming creation. In 1968, Steve Ditko, who was the man behind the revamp, described his thinking during an interview: “I was looking over the first Blue Beetle that Charlton Press put out, and it was terrible. I began thinking how it could have been handled. The ideas I had were good, so I marked them down, made sketches of the costume, gadgets, the bug, etc., and put them in an idea folder I have, and forgot about it. A year or so later, when Charlton Press was again planning to do super-heroes, I told Dick Giordano about the Blue Beetle idea I had. He was interested in trying it, so it came out of the idea file, and into the magazine.”61 About Ditko’s revitalization of a tired, old character, Giordano wrote: “[I]n one of his Wednesday visits [to the New York City Charlton office], Steve made a presentation of his ideas for the new Blue Beetle. He substituted Ted Kord for Dan Garret, the original Beetle, and kept the character in the original continuity, but eliminated the powers that Garret derived from his scarab and substituted specialized equipment for them. (I really loved the Bug—I thought at the time it was a stroke of genius.)”62

This spread: Panel detail from Blue Beetle #2 [Aug. ’67]; Blue Beetle #1 [June ’67] cover (both by Steve Ditko); and the ridiculously wordy cover (written by none other than editor Dick Giordano) of The Many Ghosts of Doctor Graves #1, with cover art by Pat Boyette; and Comic Comments #10 [Dec. ’66], Ghostly Tales #55 [May ’66] covers, both by Rocke Mastroserio. THE MANY VIRTUES OF DR. GRAVES One of the most enduring aspects of the Giordano years was his launching of Charlton’s supernatural line of comics, with story content not unlike the long-dormant Tales of the Mysterious Traveler, which deviated from the imprint’s recently cancelled “weird” anthologies, Strange Suspense Stories, Mysteries of Unknown Worlds, and tepidly named Unusual Tales. “[Giordano] was rewarded,” fanzine Champion #7 [1969] stated, “by watching them climb to the top of the Charlton sales charts.”63 Indeed, Ghostly Tales had 115 issues and The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves lasted for 72 issues.

Best of the two—and winner of the 1967 Alley Award for “Best Fantasy/Science Fiction/Supernatural Title,” in its debut year—was the latter, whose title character, Dr. M.T. Graves, was story host and oft protagonist (not unlike DC’s Phantom Stranger). About the mouthful of a title, Giordano said, “Ghostly Tales was selling, and we wanted to use the word ‘ghost’ in another title. Pat [Masulli] said, ‘We’ve got to come up right away with another ghost book, it’s got to have “ghost” in the title.’ So we started thinking up dozens of titles, and we ended up with ‘graves,’ which basically implies ‘ghosts.’ But somehow The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves doesn’t seem as clever as Ghostly Tales.”64

Regarding The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves #1 [May ’67] cover artist Pat Boyette, the editor said, “I thought his stuff was very specialized. He couldn’t do romance, couldn’t do war, but he could do this mystery stuff. I think I gave him basically Ghostly Tales and Many Ghosts.”65

Rocke Mastroserio

Rocco “Rocke”

Mastroserio [1927–1968] was born on Staten Island and raised in Manhattan’s “Hell’s Kitchen.” Attending the School of Industrial Arts, he became friends with Joe Orlando, and Mastroserio broke into comics working for L.B. Cole and later doing staff chores for All-American Comics. Soon he was inducted into the U.S. Marines and stationed at the Corps Institute in Quantico, Virginia. After the war, he attended the Cartoonists and Illustrators School, studying under Burne Hogarth, and he rejoined the comics profession. In 1955, with the industry in recession, he started at Charlton, where he worked for the next 13 or so years.

A biographical sketch appearing in Creepy #16 [Aug. 1967] states, “Former Charlton editor Pat Masulli helped him, by giving free rein to experiment, and present editor Dick Giordano also works closely with him.”66

It was his assignment inking Steve Ditko on the revival of Captain Atom that brought Mastroserio to the attention of comics fandom, and he immediately developed a reputation as a helpful and exceedingly friendly professional. Plus, of course, he had developed into an excellent artist, particularly effective when Charlton launched its Code-approved supernatural line of comics— Ghostly Tales, The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves, Ghost Manor, etc.—where his solid storytelling and robust inking were much in evidence. His artwork was, to put it plainly, getting better all the time.

Mastroserio also helped out newcomers at the Derby publishing house. “Grass” Green shared, “ ’Bout the best thing—re: me working for Charlton— was meeting and becoming friends with Rocke Mastroserio, who was a source of constant encouragement. I was only over to Derby a coupla times; Rocke and I mostly wrote each other. He thought that, with more work, I’d get better, and encouraged me to keep drawing and submitting stuff.”67

The artist joined the ranks of Warren Publishing, where he contributed exceptional artwork to the horror titles, and he also shared his talents with fandom, as is evident by his excellent cover featuring Ghostly Tales story host Mr. L Dedd for Comic Comments #10 [Nov./Dec. 1966]. Mastroserio also kept up a steady correspondence with that fanzine’s co-editor, Gary Brown, with whom he provided insider details about his Charlton work and opinions on peers.

“Incidentally,” he wrote Brown, “I’m not scheduled to ink the next Captain Atom.* I’m just too bogged down with work… If I were editor, I’d have Steve ink it for that ‘special look’ of his work. But he’s overloaded, so that’s out.

“As for Ditko, I for one can’t get over his imagination. There just isn’t anyone that I can think of who can match it. His version of Blue Beetle is a sure winner! And… he’s a very nice person. A good Joe!”68

Good Joe Gill was effusive regarding

Rocco Mastroserio

his pal. “Oh, Rocke, he was a great guy. He was deaf and he loved his artwork. He was a good artist. He and I were best friends. I talked a lot, and he didn’t hear me because he was deaf. We got along great! He loved to gamble.”69

Shockingly, Mastroserio was struck dead by a heart attack, in March 1968, a tragedy that sent shock waves through fandom. Don and Maggie Thompson’s Newfangles fanzine [#8, Mar. ’68] reported, “Mastroserio was (please pardon us for editorializing here) one of the finest comic artists in the business today and was continuing to improve. He was also a warm and gentle man who seemed honestly to have no idea how good he was… His loss is the greater because he was constantly improving.”70

Comic Comments courtesy of Mike Frfiedrich.

Writer Steve Skeates excelled at writing the spooky exploits of Dr. Graves, once using story ideas he intended for an issue of DC’s The Spectre, and seeing that tale, “Ghost Driver” [Many Ghosts… #11, Jan. 1969], rendered in authentic Doctor Strange style by the Mystic Arts Master’s own creator, Steve Ditko!

Another excellent Dr. Graves saga by Skeates was #5’s “Best of All Possible Worlds,” [Jan. ’68] as John Wells explained, “wherein a comic book fan was pulled into the pages of a Charlton comic and he had decided whether to go back into the real world with his girlfriend.”71

Ghostly Tales was hosted by Mr. L. Dedd and it set the template for Charlton’s numerous supernatural anthologies to come. Given his subsequent success gathering an astonishing roster of talents for his House of Secrets and Witching Hour at DC, Giordano said, “People that I thought were so good, Charlton hadn’t anything to offer them. Alex [Toth] was one, Gil Kane was another. I knew and loved their work, but I didn’t think I had the right to even ask them.”72 Still, the considerable talents of Boyette, Ditko, Mastroserio, Jim Aparo, and newly-arrived Rudy Palais, in GT’s first few years, was hardly anything to sniff at!

*Does this refer to the uninked Captain Atom #90 that remained in inventory until John Byrne inked it for Charlton Bullseye #1–2 [’75]?

D.C. GLANZMAN David Charles Glanzman [1928–2013] was the youngest brother of talented siblings Lew and Sam Glanzman (the latter, of course, a prolific Charlton artist), and he was looking for work in mid-summer 1965. Fortuitously, as he settled into his managing editor position at the company, Dick Giordano was in need of a production assistant and Sam suggested Dave (who was also known by his first two initials, D.C.).

Asked by Christopher Irving if he had any help in the Charlton office, Giordano replied, “I did have a secretary and one staff artist, D.C. Glanzman, who made all of the corrections. Occasionally, books had D.C. Glanzman down as a writer. That was Steve Ditko really trying hard not to explain that he did everything, but Dave and I got to be very friendly.”95

Confusion over Glanzman’s writing credits has persisted over the years, as those listed in BB and Question stories in Blue Beetle #1–5 were taken at face value, but Giordano insisted Glanzman simply agreed to allow Ditko to use, without compensation, his name as writer. “I have no idea why Steve didn’t want to take credit for it, but he didn’t,” Giordano said. “Dave Glanzman worked in the office, as a board man, making corrections, taking stories to New York for Code approval, things like that. We just asked him for permission to use his name as writer on some of Steve’s stories.”96 (Though Glanzman declined the author’s interview request in 2000, he did share his ex-boss’s letter of recommendation from 1967.) It’s no wonder that Steve Ditko creations Mr. A and The Question (the latter an Action Hero back-up in Blue Beetle) pretty much look identical, as even the originator mixed ’em up! “The Question (and Mr. A; I can’t seem to separate the two),”97 Ditko related in a 1968 mail interview.

Mr. A, a merciless character manifesting Ditko’s Ayn Randian philosophy, was created simultaneous to The Question, who appeared first in witzend #3 [1967].

Ditko shared background on The Question: “When Blue Beetle got his own magazine, they needed a companion feature for it. I didn’t want to do Mr. A, because I didn’t think the Code would let me do the type of stories I wanted to do, so I worked up The Question, using the basic idea of a man who was motivated by basic black-&-white principles. Where other ‘heroes’ powers are based on some accidental super-element, The Question and Mr. A’s ‘power’ is deliberately knowing what is right and acting accordingly. But it is one of choice, of choosing to know what is right and choosing to act on that knowledge in all his thoughts and actions with everyone he deals with. No conflict or contradiction in his behavior in either identity.” Ditko added, “He isn’t afraid to know or refuse to act on what is right no matter in what situation he finds himself. Where other heroes choose to be selfmade neurotics, The Question and Mr. A choose to be psychologically and intellectually healthy. It’s a choice everyone has to make.”98 In late summer 1968, though the Action Hero line had been cancelled, Charlton released the one-shot Mysterious Suspense #1 [Oct. ’68], an issue entirely devoted to (presumably) material meant as Blue Beetle back-ups.

This page: Dick Giordano’s 1967 letter of recommendation for D.C. Glanzman; panel detail from and cover of Mysterious Suspense #1 [Oct. ’68], with art by Steve Ditko.

The Question

The Question vignette coloring by Tom Ziuko.

FROM OUT OF THE FILING CABINET THEY CAME It’s commonly known in the trade as the “slush pile,” a batch of mail every publication accumulates: unsolicited queries and samples from hopeful contributors. In Charlton’s case, it was amassed in the filing cabinet drawers in the vacated office of Pat Masulli, and those submissions were scoured by the incoming Giordano. Asked how he discovered James Nicholas Aparo [1932–2005], whose first comics work appeared in Go-Go #6 [Apr. 1967], the editor said, “From a letter I found in the file cabinet I inherited. Most of the new people I got at Charlton were from the mail my predecessor never read, but just stuffed into the file drawers. I called Jim up, and he came down from Hartford, we talked for half-an-hour, and I said, ‘I’ve got something for you: How about “Bikini Luv”? It’s humor. Sexy girl, closer to the Archie style, really.’ He said, ‘Well, I’ll take a shot at it.’”119

Connecticut-born, self-taught artist Jim Aparo, who had been working in a dull advertising job at the time, remembered that his introduction to Charlton took place while on summer vacation. Lacking the money to do anything during the break—Aparo had just purchased a new home and was raising three kids—the

artist took the hour-long ride to Derby armed with a portfolio of work samples and comic-book material he produced just for his appointment with Giordano. Aparo was relieved as he stepped into the Charlton Press building having finally made a breakthrough and got a meeting with the new editor after having been rejected by former editor Pat Masulli. “Anyway,” Aparo told Jim Amash, “when I met Dick, he was the man in charge at the time. I showed Dick what I could do. It was my own stuff that I made up. I would take comic pages that existed from books and write the copy down like a script, ignoring the artist who did it. I said, ‘Now, how would I do this if I was drawing it?’ Dick saw the possibilities were there. He liked what he saw, so he gave me a script to do.”120 The humble and reliable Aparo was a rarity in the business, as he entered the comic book industry a fully-realized, exquisitely talented artist, a dependable professional Jim Aparo able to pencil, ink, and even letter, all in an instantly recognizable and unique style. He had previously produced regional newspaper comic strips, one about golfing, but given his devotion to comic books as a youth, Aparo enjoyed finally breaking into the field—and he appreciated the freedom afforded by Charlton. “I never asked to do anything,” he said. “Dick gave me what he thought I could do and I did it. That’s the kind of guy he was. He let you be your own boss. If you had trouble, give him a call. But otherwise, do it.”121 During the Action Hero years, Aparo drew romance, Western, science fiction, and supernatural stories, as well as rendering action heroine and Captain Atom chum Nightshade, “Thane of Bagarth” (a sword&-sorcery serial), “The Prankster” (starring a mischievous rebel in a dystopian future), and “Wander” (a mash-up of super-heroics, science fiction, and Westerns), as well as covers. After Giordano quit, the pragmatic artist continued to accept Charlton assignments while also freelancing for DC, and Aparo produced his greatest Charlton work, The Phantom, during managing editor Sal Gentile’s reign of 1968–72. Another extraordinary talent Giordano pulled from a Charlton file drawer was Pat Boyette—San Antonio native son and renaissance man Aaron Patrick Boyett, Jr. [1923–2000]—whose eclectic, fascinating, and diverse professional life included careers as television news anchor, B-movie filmmaker, and newspaper comic strip artist, and yet, as a certain point, he still felt something was missing. As Tom Spurgeon related, “In the mid-1960s, Boyette was commiserating with a friend in San Antonio over those aspects of their careers each found unfulfilling when a shared artistic interest led them on a lark to pursue jobs drawing comic books. Following up on a Charlton comic book randomly selected by the friend, Boyette called the company, made sure they were looking for artists, and sent along samples. When Charlton replied to his mailing, it was to say the company was re-structuring, and they would contact him in a year. Boyette recalled putting the thought of working for Charlton out of his mind.”122

Pat Boyette

Chapter Eleven Meet Jonnie Love and the Hippies

A TIGER BY THE TAIL Some 40-plus years after he resigned as Charlton’s managing editor of their comics line—the most consequential tenure of any employee in the history of Charlton Comics—Dick Giordano still felt a twinge of disappointment about the company. In 2009, he told a convention audience, “What happened was, because our marketing department at Charlton was not active in promoting the Action Hero line, the sales were low, and that was my real main reason for leaving there. I felt like I had worked very hard on that line and it wasn’t being backed up by anything. When I left, I don’t think they cared much, so, after I left in ’67 (something like that), they just cancelled the whole line. Sal Gentile was the editor, my replacement at the time, and Sal was a very sweet guy, but wasn’t very aggressive, and I guess he didn’t work hard enough to keep [the Action Heroes line] going.”1

Ultimately, due to its overall set-up, Giordano felt Charlton missed a great opportunity. After all, as far back as 1958, Newsdealer magazine, in an article headlined “A Capital Idea,” realized its potential, as the trade journal gushed about the all-in-one set up at Charlton: Something of a phenomenon in the world of publishing is an extraordinary one-stop shop nestled among the gentle rolling hills of central Connecticut. Here, it is not only possible, but commonplace for an idea to enter through one door and finished publications to leave from another.

What’s more, the very trucks speeding copies to various parts of the country are also owned and operated by what may be the most versatile and comprehensive publishing operation anywhere!2

In an interview with the author, Giordano said, “Well, the unique thing about Charlton, and the thing that always bothered me, was that they had a tiger by the tail, but didn’t know it. It was the only publishing operation I’ve ever heard of that was contained in one building—from concept to shipping! It took place within the same walls, within perhaps 100 yards of each other… Yeah, Charlton had it all. And that’s exactly what they had that nobody else did and, for example, if they wanted to go head-to-head with DC Comics—quality of the artwork, quality of the stories, quality of the printing and distribution—they probably could’ve done it at twothirds of the cost that DC was paying. And if they had done

This spread: Above inset is the public service announcement by the creators of Jonnie Love, which appeared in the Charlton Romance Group only a month after the character’s 1968 debut. Opposite are Charlton Comics covers from the Sal Gentile years. that, they really could have turned the comic book publishing business on its ear. But they chose to be junk dealers, they really did. I mean that in a literal sense: they thought they were producing junk; they thought of all of it as junk; they didn’t think it had any commercial value; they didn’t think there was any reason for them to be serious about it… the music magazines were making the money. I don’t even know why they published comics, to tell you the truth… just to keep the presses running was probably the biggest reason. And I think they felt good about somebody like me taking over and caring about the comics line, because, once I got there—this might’ve been true for [executive editor] Pat [Masulli], too, but it was much harder for him because he was also with the music business, and crossword puzzle books, and the humor books, and so forth—but once I got there, nobody

Chapter Twelve Charlton’s Cartoon Cavalcade

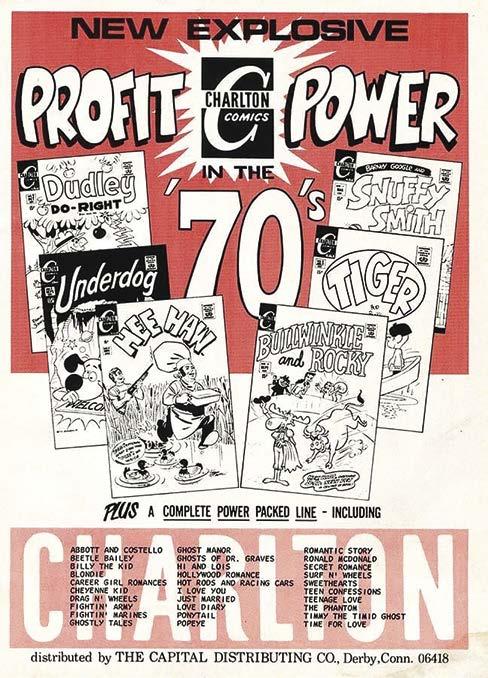

LICENSED TO PRINT As the new decade dawned for Charlton, in addition to sticking with its tried and true genres of war, supernatural, hot rods, and romance comics, which were still selling in reasonable numbers, the publisher made a major foray into licensed property comics. In 1970, titles featuring characters from Hanna-Barbera, Jay Ward, and Gamma cartoons; King Features Syndicate comic strips; and one-off Hee Haw and Ronald McDonald properties constituted close to half the publisher’s total comic book output. (By then, Westerns were considerably less reliable sellers, with 11 titles in 1960 dwindling down to two by the end of 1970.) And to produce those 22 titles, editor Sal Gentile was in a mad scramble to find “cartoony” cartoonists to draw the material.

Ray Dirgo was one of Gentile’s best and longest-lasting discoveries, and he became well-regarded for his Flintstones work. He recalled, “The first barrage of work came in summer 1969, when Charlton Comics signed to do the Hanna-Barbera comic line. Sal assigned me to write and draw the covers for the first seven comics of that line they published. They included: The Flintstones, Magilla Gorilla, Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, Quick Draw McGraw, Top Cat, and The Jetsons.”1

Dirgo continued, “In the beginning, I did most all The Jetsons, Top Cat, and Magilla Gorilla books, too. The Top Cats often required the shoehorn style of cartooning, because the scripts were constantly putting six cats and a policeman in one panel.” He added, “The flow of Hanna-Barbera work for me was incredible. Charlton imported a lot of artwork from Mexico. Maybe it’s because of extended siesta time, but they had many problems with late work. When that happened, I got more work.”

Along with Dirgo, Gentile found an array of cartoonists, including far too many anonymous hands whose work, to this day, remains uncredited (though, in truth, a chunk of the material was substandard, to the great dismay of the licensors and their overseas partners). Among the recognized artists, there was Frank Johnson, Frank Roberge, Paul Fung, Jr., Bill Yates, Phil Mendez, as well as an old hand Charlton wanted to use on a new venture involving the licenses. Tony Tallarico told Jim Amash, “I did a whole slew of coloring books for Charlton. They wanted to get into the coloring book field, and they had the license from Hanna-Barbera and a few other companies. I did all of them, and there was nobody that did a coloring book at Charlton but me.”2 WILDMAN LET LOOSE Another seasoned cartoonist, one who had worked for the Derby publisher during the Masulli years, was soon hired to be the overworked managing editor’s right-hand man. George Wildman had his own studio supplying art to Connecticut advertising agencies when Gentile gave him a call, right after Wildman’s biggest clients had moved to the West Coast. “I got an offer from Charlton because I had done some freelance for them starting in the late ’50s for their comic book division, fill-in stories. You know, fillers. And they made me an offer: Would I take a position as assistant editor? The advertising business, believe me, is a rat race.”3

Despite Wildman champing at the bit to work as a full-time cartoonist (especially for a publisher who had only just recently nabbed the rights to a character beloved by the longtime fan), but there was a big problem. And—no surprise here!—that problem was money.

This spread: Above is distributor trade journal ad promoting Charlton’s big push into licensed comics. Opposite is a heavily altered version of Hanna-Barbera Parade #10 [Dec. 1972] cover.

Chapter Thirteen The Plant and the Process

UNDER ONE ROOF In a splashy 1973 Sunday newspaper feature celebrating the storied comic strip legacy of Connecticut, writer Bill Crouch, Jr., shifted focus from strips to the state’s all-in-one comic book outfit. “The most visible indication of Southern Connecticut’s ‘Cartoon Power,’” he wrote in The Bridgeport Post, “is Derby’s huge Charlton Publications building. Long and low, the red-brown factory has almost a sinister look as it stretches from Division Street down along Pershing Drive.”1

Encompassing an expanse of between six and nine acres (sources vary), comics editor George Wildman estimated Charlton annually printed about 70 million comic books comprised of over 40 bi-monthly titles.* For Charlton Spotlight, the editor described the usual routine for the operation: “Let’s look at a given week: you see, Charlton Press was humongous in size. It was like six acres under one roof, one floor. One part of it had two floors and we had our own ballroom for when we had a Christmas party, or when someone was getting married, the company would offer [use of] it. I don’t know how little they charged.”2

The editor continued, “Everything was under one roof. Joe Gill was the only writer on staff. We also had a magazine division and they put out a lot of magazines. Boy, they were doing great at that. But anyway, it made it nice. We had all our engravers there, and we had our presses, and everything right out to shipping. We shipped to everywhere east of the Mississippi. Beyond that, the books went other ways. So, in a given week, Monday morning was always a staff meeting and that involved guys from the press room, from engraving, from the comics, from magazines, and so on, and reviewing what we’re doing, what management was doing, what was coming up, and what was on the schedule then. We had our own sales force; they were in there, too. Charlton Publications handled it all from publishing to distribution, and that was it. “Then, the rest of the week, you were pretty much on your own, getting all the work done in your own division, keeping all your own coordinates going—scripts going out, art coming in—coordinating the books. We had almost 50 books in our line, so I was editor, at one time, of, say, 50 comics. And it kept me going because, within comics, we had humor, we had romance, we had adventure, we had Western, and on and on. We had seven or eight categories of comics and that’s where I used a lot of good artists… Consequently, I’d go once a week into New York where we had an office, and a lot of artists would come into the city, and it was nice for them. They didn’t have to come up to Connecticut for assignments. They’d come down from Rochester or in from Chicago—not Hawaii, but anyway… And then we could have our conferences. So I would go in to New York and I would deal with King Features in person, Hanna-Barbera, and so on.”

*Ronald T. Scott, Charlton Press general manager of the late ’60s and into the ’70s, shared with the author: “At its high point, Charlton Comics was the third largest comic book publisher in the world, with production of more than 6,000,000 units each month.”3 This spread: In the ’70s, King Features devoted some of its multi-faceted educational presentation to Charlton’s soup-tonuts operation, including a slide presentation with color pix of the production process. Left, Cartoonist Profiles #20 [Dec. ’73]. All photos this spread courtesy of Donnie Pitchford.

Chapter Fourteen Charlton Takes Its Next Best Shot

THE COMING OF CUTI Amidst a rough-and-tumble Brooklyn upbringing, Nicola Cuti [1944–2020], developed a lifelong affection for space opera science fiction. It was after college and while in the U.S. Air Force when Nick Cuti encountered Creepy magazine and subsequently contributed to Warren’s horror mags as writer. After the service, he became an assistant to artistic idol Wallace Wood and, as cartoonist, Cuti created his underground comix character, Moonchild. About coming on board at Charlton, Cuti explained, “Well, what happened was, I had always been connected with Warren, right up until its demise. I was working with Woody at the studio and I discovered I really couldn’t live on $20 a week. So, there was an artist who used to come down to the studio to visit by the name of Tony Tallarico. And he was attached to Charlton. And, one day, he came into the studio, and said, ‘Nick, you know, they’re looking for an assistant editor at Charlton.’ Sal Gentile, who

had been the editor at Charlton, was being bumped up to magazines, and his assistant, George Wildman, had taken over as the editor of comics. And George was looking for an assistant, and Tony said, ‘Why don’t you apply?’ So I thought, ‘Yeah, sure. The opportunity to be working as an assistant editor at a comic book company? Sure.’ So I called up George Wildman and he offered to interview me in New York City. And I drove down to New York City, and I arrived at the city 20 minutes early for our appointment, and I thought, ‘Oh boy, no problem.’ Well, I got stuck in traffic and the traffic locked me in so that I was moving at about a half-hour to drive one block. So, I arrived [for] the appointment that I was originally 20 minutes early. I wound up being two hours late. Nick Cuti George waited for me, interviewed me, and I was hired.”1 For receiving $200 every payday, ten times the weekly salary he’d been getting from Woody, Cuti proved an excellent editor and fine writer, though his duties could be routine. “Myself and another guy by the name of Frank Bravo,” Cuti said, “the two of us were the production department… which meant that when artists would send in completed stories, we would look over the artwork, proofread it, and, if there were any spelling mistakes, we corrected them. And if there were any pieces of artwork that had to be corrected for one reason or another, we would do that.”2 Cuti continued, “At the time, the Comics Code was very strong, and so we would send our artwork to the Comics Code for approval by [administrator] Len Darvin. And then it would come back and they would sometimes ask for changes. It was up to the production department—Frank Bravo and myself—to make all the changes… Mostly, [the Code’s objections] had to do with bikinis being too brief or certain scenes being too frightening for children because we did a lot of horror comics. Or war comics that were a little bit too graphic for kids. And too bloody, or something like that. So we would change that sort of thing… We sent some very angry letters to Len about that, but I have a feeling that Darvin looked upon Marvel Comics as being more for the older kids and Charlton being for the younger kids. And that was the reason we were more heavily censored, I guess.”3

Primetime Primus

Joe Staton described his first regular Charlton series: “Primus was a licensed character from Ivan Tors (the producer of Sea Hunt) and it starred Robert Brown (who starred in Here Come the Brides). It was another skin-diver TV show, set in Florida, and there was a lot of international intrigue and stuff. It had a lot of potential, but it was shot so cheaply that there wasn’t a lot on the screen, really. Joe Gill wrote the comic, and he would throw in all kinds of stuff: Lots of spies, drug smuggling… It was before the Code allowed drug stories.”4 Of its seven issues, Primus had only two covers drawn by Staton. The artist said, “Sal liked to do photo-covers, he’d get carried away with them and spend days cutting up photos and making stills, collages. Somebody remarked how Sal would get lost for hours, putting those covers together.”

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK BELOW TO ORDER THIS BOOK!

This spread: At left is Primus #1, based on a little-remembered TV series; opposite is Joe Staton’s cover art for Comic Book Artist #12 [Mar. 2001], starring Charlton’s horror hosts and friends. Sticker image courtesy of Joe Staton. Opposite page coloring by Tom Ziuko.THE CHARLTON COMPANION An all-new definitive history of the notorious all-in-one comic book company, from the 1940s Golden Age to the Bronze Age of the ’70s. Examines Dick Giordano’s ’60s “Action Hero Line” featuring Steve Ditko and others (and inspiring Alan Moore’s Watchmen), Joe Staton’s E-Man and John Byrne’s Doomsday +1, and more. By Jon B. Cooke with Michael Ambrose & Frank Motler. (272-page FULL-COLOR softcover) $43.95 (Digital Edition) $15.99 ISBN: 978-1-60549-111-0 https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=95_94&products_id=1675