6 minute read

The Family Car(s

The Family Car(s) Part XIV Of JOHN BROOME’s My Life In Little Pieces

A/E EDITOR’S NOTE: Last issue’s installment of the esteemed Golden/Silver Age comicbook writer’s 1998 “Offbeat Autobio” detailed several anecdotes relating to his wife Peggy, who had a way with a phrase herself.

Advertisement

We continue that accounting this time around, with a sideways look at the family unit’s colorful automobiles over the years, courtesy of their daughter Ricky Terry Brisacque. The text is, as always, © the Estate of

Irving Bernard “John” Broome…. P eggy’s penchant for giving fanciful names to our household articles extended to the automobiles we owned at various times, starting with a Model A Ford, a two-seater coupe that had served as a chicken coop in the previous owner’s backyard for some years. We had to clean out the feathers and the chicken doo-doo to use it. Obviously, it didn’t look like much, but it was cheap—this was in the depths of the Great

Depression of the 1930s and $15 was what we paid for it. However, would it work? We got hold of a battery, attached it, and cranked.

After a few tries, the old flivver exploded with a roar, shaking off chicken feathers and doo-doo to all sides like a dog coming out of a lake. In spite of this spectacular demonstration of the vitality of

American industry, Peggy named the Ford “Dying Capitalism”—in those days, all the young people we knew were communists. But in time, we learned better, I’m glad to say.

Our next car was a yellow Cadillac convertible with a golf club compartment, if you please, in the rear—no one had money to buy gasoline for such a huge car which did gallons to the mile almost, so we got it for a song, for $50, and Peggy, still loyal to her ideals, named it “Comrade Cadillac.” After that came a boxy but economical Chevrolet that brought us home safe and sound, and dry, more than once through thunderstorms in upstate New York where after the War we had begun to live. Water seemed the natural element of that old Chevy—it became the “Santa Maria.”

It was followed by a big gray Nash Ambassador, a car with a “powerful warhorse of an engine” that we kept for years, but which finally succumbed when a possibly overworked grease monkey left off the screw-on cap after checking the transmission oil level. It was with much regret, some months later, that we conducted the Old Gray Mare, emitting an increasingly loud wheeze of protest, to her final resting place, a Mad Max-type junkyard in nearby Poughkeepsie.

Our last car didn’t need a nickname: a four-seater blue convertible, it came equipped with its own: the Minx, dainty and spunky as an English lass: imported, yes, because Detroit had

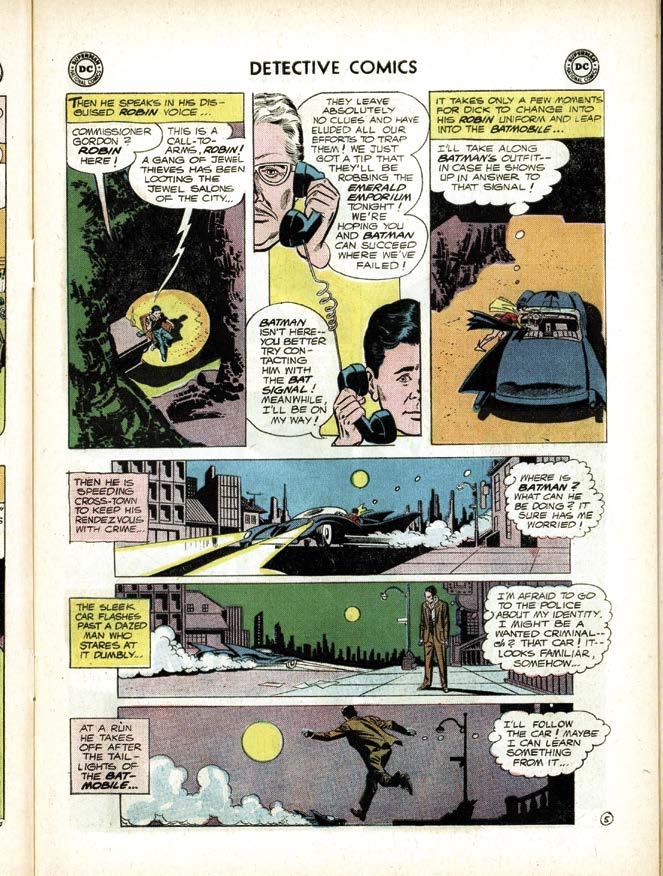

John, Peggy, & Ricky Broome in 1956. (We ran this photo three years ago, but it’s one of the few we have of Mrs. Broome, so thanks again to Ricky Terry Brisacque for the picture.) (Right:) Although John speaks this issue of some of the clunkers the Broome family owned at one time or another, at least he got to write about one of the supreme automobiles of popular fiction—the Batmobile, as per this page from Detective Comics #331 (Sept. 1964), as penciled by Carmine Infantino and inked by Joe Giella for editor Julius Schwartz’s “New Look Batman.” Thanks to Bob Bailey. [TM & © DC Comics.]

stopped making convertibles, presumably on the grounds of their being unsafe, and didn’t make them again till decades later. An incredible fact. Hard to understand. Although, come to think of it, it was a fact that might easily have made present-day cherishers of seatbelts and airbags happy since quite clearly it paved the way for the spread of those articles and for an increasing emphasis on motoring safety—if not at all on motoring joy or exhilaration or that bounding sense of freedom that comes from riding in a wind-whipped open convertible on a fine and sunshiny day.

“A Hank Of Hair And A Piece Of Bone…” Peggy Broome was once briefly concerned about losing a few strands of hair—while, behind the somewhat garish cover painting by Rudolph Belarski, her hubby had earlier written a tale about a man who got a whole new face, in the Better Publications science-fiction pulp Startling Stories, Vol. 6, #3 (Nov. 1941). The title illo is by Leo Morey. Thanks for the cover scan and artists’ IDs to David Saunders and his invaluable www.pulpartists.com website—and to Glenn MacKay and Art Lortie for the Broome title page. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

A P .S . Of Peggy Stories

She pressed me to tell her just what had gotten me angry the evening before at a friend’s house where we’d had dinner, but I was stubborn, it wasn’t anything important, and I was reluctant to explain.

“You’re only asking out of curiosity,” I charged.

She looked at me in astonishment.

“Of course!” she said.

Peggy was morose over her hair falling out during a shampoo. We played music on our recorders to distract her and cheer her up. After we finished, I remarked not very originally, “Music restoreth the soul.” “Yeah,” she responded with a plaintive pout, “but not the hair.”

Uncle Heinie

Peggy’s Uncle Heinie was already a bowed and stooped old graybeard with failing eyesight when I met him. However, he hardly seemed to change over the following decades when he easily outlasted every one of his fellow male family members, all, by the way, first-generation U.S. immigrants, and like him from the same corner of eastern Europe.

The wing of the clan that I got to know settled in quite toney Shore Road, Brooklyn (rumor had it that several Mafia bosses had their mansions there), in a solid brick two-family house. Peggy and folks downstairs and Uncle Heinie and family upstairs. When you chanced to encounter him during those years, Uncle Heinie was likely to trouble himself to explain how he happened to be still around when all the other family men of his generation had disappeared.

“I forgot to die,” he would say, a bit jauntily, giving way to what one suspicioned might have been a lifelong weakness for turning a phrase.

Once Peggy and her sister Mindelle (sixteen months between them) made so bold as to take their patriarchal uncle to task for what they considered some unfair treatment of his wife, their sainted Aunt Esther (and their mother’s sister), and Uncle Heinie on being so confronted, raised a hand before them as if he were Charlton Heston playing Moses on the heights of Mount Ararat. (Actually, a bloodline relation of his with the same last name was one of the most revered and honored rabbi-scholars in Judaism, and Uncle Heinie was not likely even for a moment to lose sight of his close connection with that illustrious personage.) you know what is the most important one of the Ten Commandments?”

The two young defenders of the rights of elderly wives were momentarily taken aback by this unexpected defensive maneuver. “Honor thy father and mother,” piped Mindelle, mostly because some answer seemed required.

“No,” their interlocutor assured them with a faintly curled upper lip and some strong professorial blinks behind the thick telescopic lenses through which he was peering down at them. “The most important of the Ten Commandments is—Mind Your Own Business!” And so saying, he turned and started up the narrow staircase to his abode above which at ninety, he could still negotiate without any assistance.

And that was Uncle Heinie.

Next issue, John Broome relates several anecdotes concerning his fellow DC Comics (and “Batman”) writer, David V. Reed.