9 minute read

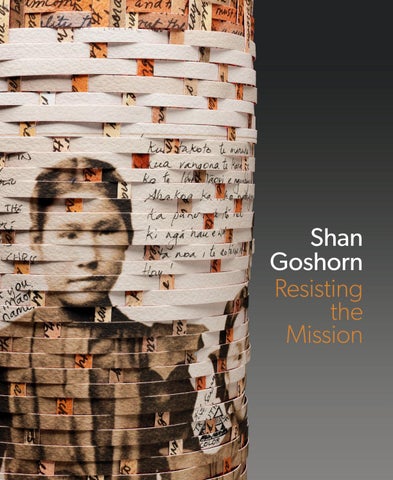

Resisting the Mission

Shan Goshorn

This exhibition has been a long time in the making, beginning when I approached my teen years and learned that both of my great-grandmother’s parents attended Carlisle Indian School.1 I’m not sure when my specific questions about boarding schools arose, but it took my relatives years to talk with me about them. I created my first boarding school basket—which was a complicated double-weave technique AND the first time I wove a photograph—in 2010. Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian Boarding School (fig. 1) received the Best of Show award at the Red Earth Indian Art Festival in Oklahoma City, resulting in coverage in the Oklahoma City newspaper.2 This is noteworthy because the write-up attracted a Native elder to make a two-hour trip and pay the entry fee to the event, with the specific plan to visit my booth and see this basket. She listened attentively from her wheelchair while I explained the research involved, the Carlisle student imagery, related text, and the weaving process. She began to weep quietly and said, “This is our piece. It belongs in a museum. It tells our story.” I was deeply moved by her response and slowly found myself inspired to deliberately begin creating work to “tell our story.” In 2013, I received a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, which allowed me access to the archives of the Smithsonian Institution, including the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Anthropological Archives (NAA). It was part of my family knowledge that we had many relatives who attended Carlisle, but it was not until I actually saw their names on the Carlisle student roster that I realized the resounding power that written words embody. As I had communicated in advance with several curators involved in my fellowship about specific interests, they pulled many boxes of photos for my perusal.3 At the NAA, the very first photo I viewed featured a large group of young Carlisle students seated seventeen rows deep (fig. 2). Their wool military uniforms, shorn hair, and unsmiling brown faces shook my mother-heart to the core. I had to excuse myself to collect my composure. It was the goal of the Carlisle Indian School’s founder, Richard H. Pratt (fig. 3), to stamp out anything that was slightly reminiscent of Native culture, punishing the children frequently and often harshly for the crime of “acting Indian,” especially for speaking their tribal languages.4 In one of his famous propaganda speeches, Pratt coined the phrase “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” which became the guiding mantra for subsequent boarding schools that sprang up all over the United States and Canada.5 As my research continued, I read multiple accounts of confused children who, despite years of enduring this “social experiment,” knew they did not

Advertisement

1. Shan Goshorn, Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian Boarding School, 2011. Woven basket: Ink, archival pigment, and acrylic on paper splints. Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, NJ. Museum purchase, acquisition fund; 2015.12.a, b. Photo: Peter Jacobs.

2. John. N. Choate, Carlisle Indian School, 1884. Albumen print. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA, PA-CH2-001.

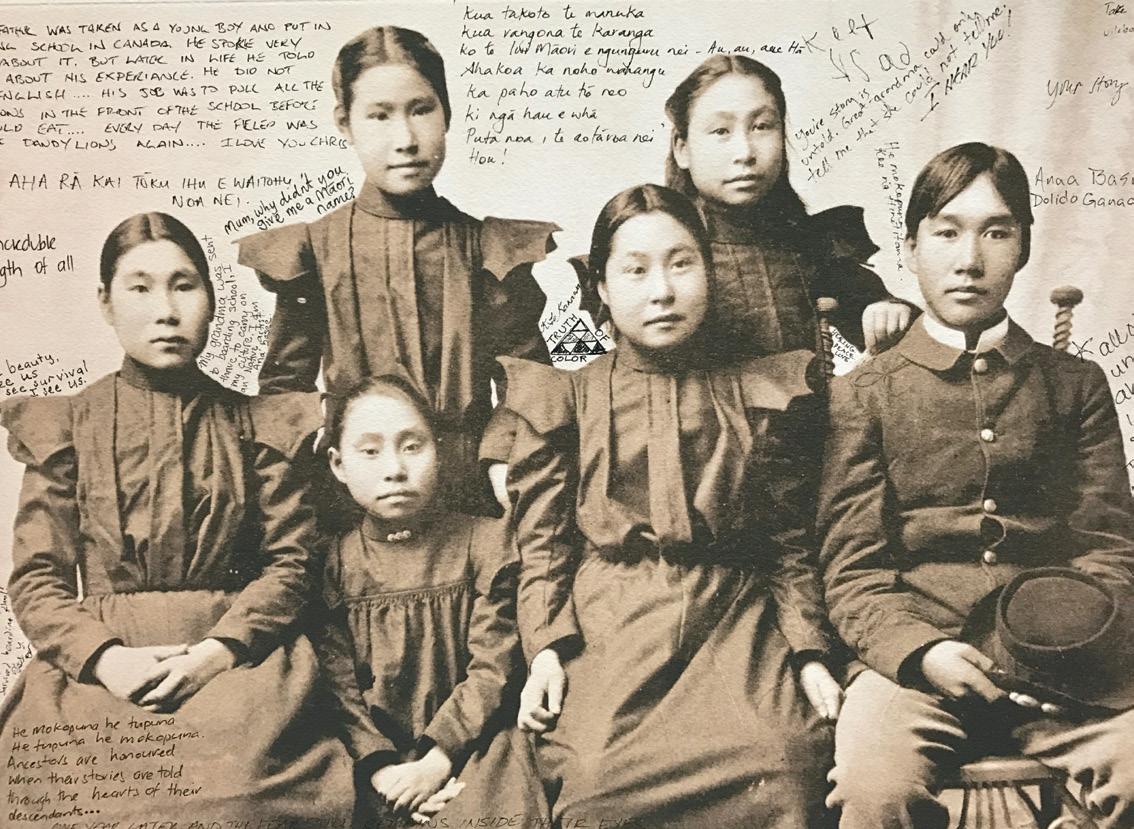

OPPOSITE Detail of print of Alaskan Indians for Resisting the Mission prior to cutting into splints and weaving.

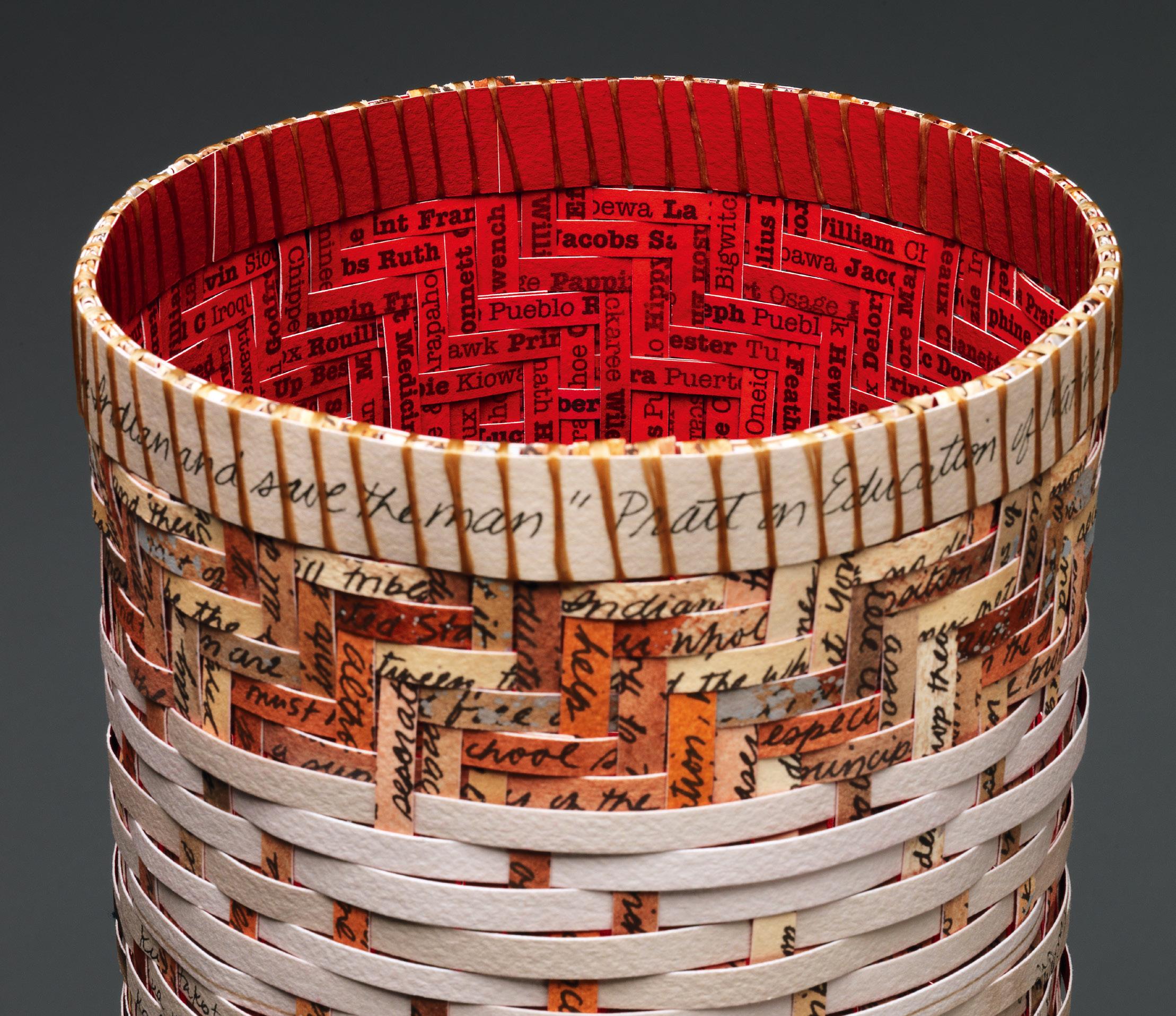

3. John N. Choate, Richard Henry Pratt, n.d. Albumen print mounted on card. Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle Indian School, PC 2002.2, folder 1. fit into white culture. When they returned to their people, they looked, dressed, and acted very differently than the children who had left, many no longer able to speak their native tongue due to Carlisle’s strictly enforced rules. One narrative recounts a boy’s reintroduction to his family; his inability to understand anything his grandmother said led her to finally ask, “Then who are you?”6 The attempt by the US government to eliminate all Native practices almost worked. Carlisle graduates didn’t or couldn’t teach their children their language, customs, and spiritual beliefs. As a result, three generations of Native culture were silenced. Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence—seven pairs of baskets (fig. 4)—was conceived to involve as many Native voices as possible to address this void. The before-and-after images were chosen after viewing photographs from countless museums and historical facilities; these images were enlarged to approximately 15 by 19 inches (fig. 5) and either hand carried or mailed to almost a dozen communities, asking participants to write their own personal messages on the surface of the photographs (fig. 6). It is these original documents that were cut into splints and woven with Pratt’s infamous speech. The interior of this set of baskets is printed with names from the Carlisle student roster and painted a deep red, symbolic of Native people (fig. 7). I followed my weaving with a social media request asking for donations of cedar, sage, sweet grass, and tobacco along with any personal notes the participants cared to add. From these contributions, my daughter Neosha and I created enough bundles to place on each individual grave in the student cemetery; we carried these to Carlisle and included a sage ceremony

4. Shan Goshorn, Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence, 2017. Woven baskets: ink, archival pigment, and acrylic on paper splints, polyester sinew.

OPPOSITE TOP LEFT

5. Before-and-after photographs for Resisting the Mission in the artist’s studio, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2016.

OPPOSITE TOP RIGHT

6. Detail of print of Alaska Indians for Resisting the Mission, prior to cutting into splints and weaving.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM

7. Interior of basket from Resisting the Mission.

8. Shan Goshorn placing bundles on each of the grave markers in the Carlisle Indian School Cemetery, Carlisle, PA, 2016. Photo: Neosha Pendergraft. with our prayers as we visited every one of these deceased children, who were never able to return home (fig. 8).7 It was a tremendously powerful experience for me. While boarding schools are not the only subject matter I use in my work, my commitment to the topic remains consistent. After the creation of Educational Genocide, Dickinson College, which is located near the Carlisle Indian School, approached me about having a solo exhibition featuring only Carlisle baskets. I turned down several repeated requests, as it seemed too big a commitment. But in 2016, I finally felt led to accept this offer, in part due to the timing; 2018 is the hundred-year commemoration of the closing of this school, which was such a source of generational trauma. There is healing that desperately needs to happen. Giving Native people an opportunity to add their voices to this work feels like a small step toward helping us reclaim our stolen voices.8 It is my prayer that these baskets will help inspire a new dialogue to spark and generate such changes. I wish to express my sincere, grateful thanks to my family, friends, and colleagues who have encouraged and supported me during my quest. But most of all, I acknowledge the ancestors who have had a strong, stable hand in guiding me. Repeatedly, the very material I needed (photos, documents) would show up unexpectedly…the ancestors made it clear from the beginning that they were not just supportive of my work but rather, they were IMPATIENT for this information to be shared.

These are OUR stories.

NOTES

1. Mose (Moses) Powell and Elkan (Elkany) Wolf (Wolfe).

2. Daily Oklahoman, June 2011. I hauled this basket back and forth between my home in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and father’s home in North Carolina, during his final illness. At one point, I was working on it ceaselessly, during many quiet hours at his bedside. I could not have poured more sorrow into this piece, but it felt appropriate. It was a gift to have that kind of connection made all the more powerful during his transition.

3. Heather Shannon and Rebecca Trout, both of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; and

Gina Rappaport of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

4. On Indian boarding schools in general, see David Wallace Adams,

Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School

Experience, 1875–1928 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995).

For Carlisle, see Genevieve Bell, “Telling Stories Out of School: Remembering the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 1879–1918” (PhD diss., Stanford University, 1998); and Jacqueline Fear-Segal, White

Man’s Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

5. Richard Henry Pratt, Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction (1892), 46–59, repr. in Richard H.

Pratt, “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites,” Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the “Friends of the Indian,” 1880–1900, ed. Francis Paul Prucha (Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), 260–71. 6. Floyd Red Crow Westerman, interview with Charla Bear, in “American

Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many,” Morning Edition, NPR, May 12, 2008. For a transcription of the news story, see “American Indian

Boarding Schools Haunt Many,” NPR, accessed June 18, 2018, www. npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16516865.

7. On the remains of the Indian children buried at the school, see

Fear-Segal, White Man’s Club; Fear-Segal, “The History and Reclamation of a Sacred Space: The Indian School Cemetery,” in Carlisle

Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, & Reclamations, ed. Jacqueline Fear-Segal and Susan D. Rose, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 152–84; Barbara Landis, “Death at

Carlisle: Naming the Unknowns in the Cemetery,” in Fear-Segal and

Rose, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 185–200; and J. W. Joseph,

Hugh Matternes, and Matthew Rector, Archival Research of the Carlisle Indian School Cemetery: U.S. Army Garrison, Carlisle Barracks,

Carlisle, Pennsylvania (New South Associates Technical Report 2635,

Contract W912P9-16-D-0015, Task Order 6, July 5, 2017). See also

“Cemetery Information,” Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource

Center, Archives & Special Collections, Dickinson College, http:// carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/cemetery-information.

8. Postcolonial scholarship has focused considerable attention on the role of voice in society. Regarding Indian boarding schools, see Barbara K. Carbonneau-Dahlen, John Lowe, and Staci Leon Morris, “Giving

Voice to Historical Trauma Through Storytelling: The Impact of Boarding School Experience on American Indians,” Journal of Aggression,

Maltreatment and Trauma 25 (2016): 598–617.

OPPOSITE Shan Goshorn, Three Sioux Students from Resisting the Mission (detail), 2018, cat. 2.5.