1 minute read

CREATIVE WRITERS: THE CANLIT CHILDREN OF TRENT

by Sean Kane, author of Raccoon: A Wondertale.

For the TRENT Magazine excerpt of Raccoon, please see page 25.

I can’t claim that Trent made me become a writer, but it is a surprise to see how many novelists it did create. The reason is historical. Trent in the early ’70s was at the forefront of a national campaign for a Canadian identity and literature. For Canada to express its dreams, it needed to support its own struggling writers and publishers. In 1972, a Royal Commission on Book Publishing revealed the extent of the foreign domination of the book trade in Canada and recommended government funding of an emerging national literature. In 1975, To Know Ourselves:The Report of the Commission on Canadian Studies by Trent’s founding president Tom Symons demonstrated the foreign influence on faculty hirings and research interests in the nation’s universities and called for more attention to the study of Canada. Trent’s Canadian Studies program began in 1972, the year Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals won re-election with the campaign theme “The Land is Strong.” The Canadianization of Trent in the 1970s seemed as urgent as its Indigenization is today.

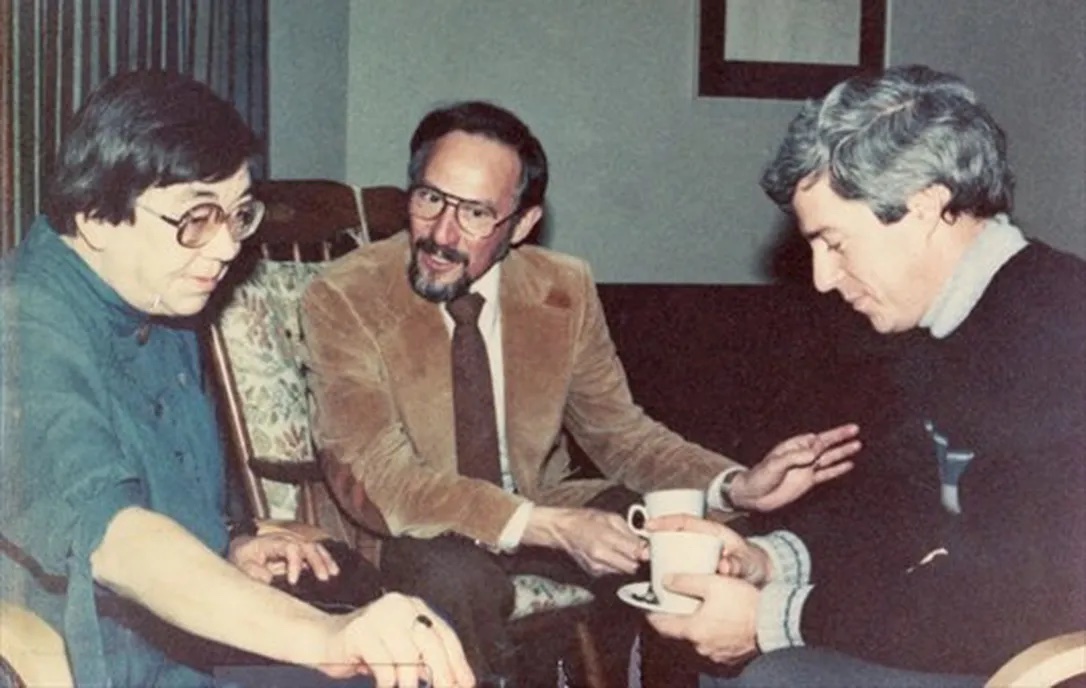

In 1973, the novelist Margaret Laurence, then at the height of her reputation, made her home in Lakefield and was welcomed by a Trent gala involving writers from across Canada. One of the guests, A.J.M. Smith, a poet of the 1930s, donated his library of early Canadian books to Trent, to be housed in the room that bears his name. On becoming Trent’s chancellor in 1981, Laurence squelched an impulse to de-fund Trent’s college system by threatening to resign. A decade later, on becoming chancellor, Peter Gzowski, a popular CBC Radio host and regular promoter of Canadian writers, declined to emulate Laurence’s gesture when I invited him to.

No accident that Cathy Bacque ’78 and Anne McClelland ’76, the daughters of Toronto publishers, came to Trent. And the children of writers: James ’70, the son of poet and playwright James Reaney; Hilary, daughter of Dennis Lee (Alligator Pie!), who would visit the University at least 10 times; Jenny, who later accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature on behalf of her mother, Alice Munro; (briefly) Penny, whose father Pierre Berton was a best-selling author of books about Canada’s defining events and personalities. Several Trent graduates opened book stores; others went into publishing, such as Jennifer Murray ’76, director of marketing at Penguin Books Canada.

In the 1970s and ’80s, an amiable English major named Linwood Barclay ’73 would go on to become a well-known novelist. And a reserved philosophy major named Yann Martel ’81 would win the Booker Prize. His first novel, Self, contains scenes set at Trent, and was probably written when he lived at “the Manor,” later the home of Trent rowers. Richard B. Wright ’70, who took a degree in English, won the Governor General’s Award. Honorary degree recipient Dr. Julie Johnston won it twice for young adult fiction. There is also the young adult novelist Holly Bennett ’75, novelist and short story writer Craig Davidson ’94, children’s book author Troon Harrison ’90, crime-mystery writer Michael Johansen ‘84, novelist and children’s book writer Paul Nicholas Mason ‘76, fantasy novelist Kate Story ‘86, and songwriter-novelist Christopher Ward ‘67. The 1970s tradition of the Writers Reading Series continued, most recently hosted by Lewis MacLeod, son of the short-story masterpiece author Alistair MacLeod.

Then there are the poets and playwrights—too many to list. Many belonged to the spirit of the time, and are summed up for me by Ian Arlett reading his mind-altering zen poems in the smoky air of the Jolly Hangman pub.

The styles of A.J.M. Smith and Peter Gzowski served their age as well. This brings me to wonder if Trent could name rooms and buildings after writers who are enduring national treasures. Isabella Valancy Crawford is one. She was the only woman to make a living by her writing in 19thcentury Canada when the book culture was controlled by men. She took on racism, patriarchy, social class, inhibited sexuality, and war, while promoting a commonwealth in nature where animals, people, and the forest spirits are equals. Her tombstone in Little Lake Cemetery has the inscription: Poet, by the Grace of God

My own story is timely, not enduring. I came to Trent with its pot lights and desk lamps because I didn’t want to grow old teaching under fluorescent lights at U of T. On the committee interviewing me was Orm Mitchell, son of the legendary writer W.O. Mitchell. Then there was Ian McLachlan, who seduced me with the words: “You can teach and write at the same time here.” To prove it, he produced the manuscript of his novel, which I passed to my father—then president of Macmillan of Canada, publisher of mainstream Canlit. Ian’s Seventh Hexagram was a finalist for the Governor General’s Award, having won the Books in Canada First Novel prize. It was followed by Helen in Exile,

published in London and New York. When we sketched the plan for the future Cultural Studies Department on a serviette at the Delta Chelsea Hotel in Toronto, we made sure to claim creative writing in its academic mandate.

I didn’t write the novel Ian promised I would until 25 years later. And it was about Trent. Virtual Freedom was displayed in airport bookstores and front of store stacks in Chapters. My brief fling with being an author was affirmed by Tom Symons appearing at the Leacock Humour Awards to support me (Harry Symons, his father, won the first Leacock Medal in 1948; I didn’t). Also at my table was Andrew Pyper, now an international best-selling novelist. He lived in Peterborough at that time as Trent’s Writer in Residence with Leah McLaren ’95, a Cultural Studies major, soon to be a Globe and Mail columnist and fiction writer.

How does my Raccoon Wondertale fit into the Trent picture? In the summer of 2019, my agent was courted by “scouts” —scouts are people employed by international publishers to seek out hot manuscripts. New York editors were gossiping mischievously, daring each other to publish my portrait of President Donald J. Trump as the raccoon “Meatbreath.” Commercial publishing is not for the faint-hearted. At a troubled time when I was writing the final chapter, Siobhan O’Connor,

Trent graduate and long-serving associate director of the Writers Union of Canada, stepped in to help. Thanks to two Trent novelists, Don LePan (honorary D.Litt.) and Julian Samuel ’74, my book was picked up by Guernica Editions. And there, by the luck of Trent community, it landed on the screen of Dylan Curran ’15, the sales and marketing specialist, who turned out to be a Trent grad.

Dylan advised me to mention Raccoon with the reminiscence “Trent in High Autumn” written for the Trent Alumni Alma Matters e-broadcast and social media. From this publication and posts, the book slipped out into cyberspace, prompting her to release the marketing data to online bookstores and retailers in 14 countries. I woke up one morning to find my book listed for sale at the Harvard Book Store and Walmart.

Did Trent make me? No. I came here already formed by the Toronto nationalist publishing scene. But Trent made my novels what they are. If anyone wonders why I’m unable to focus on a single main character, it is because of Trent. In Raccoon, my hero is a community. And the community is full of well-known Canadian authors disguised as raccoons, especially Margaret Atwood aka “Touchwit” (she got back at me in her afterword). Ours was the first university in the world to award her an honorary degree. That was 50 years ago, 1973, the year I came to Trent.

Continuing this tradition, future writers attending Trent can study Creative Writing: www.trentu.ca/english/programs/undergraduate/plans-study/creative-writing or Journalism and Creative Writing (B.A. andDiploma): www.trentu.ca/futurestudents/degree/journalism-and-creative-writing