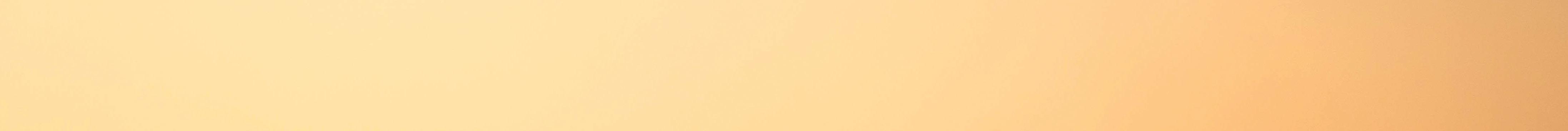

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2025

WHY DO WE NEED PLANT DATA? AT A CROSSROADS THE OKAVANGO

WADDLE WE DO WITHOUT THE PENGUINS? ON THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION

HOW CAMERA TRAPS ARE SAFEGUARDING NAMIBIA’S NATURAL HERITAGE

WHY DO WE NEED PLANT DATA? AT A CROSSROADS THE OKAVANGO

WADDLE WE DO WITHOUT THE PENGUINS? ON THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION

HOW CAMERA TRAPS ARE SAFEGUARDING NAMIBIA’S NATURAL HERITAGE

824,268 km²

21 March 1990 INDEPENDENCE:

CURRENT PRESIDENT: Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah

Multiparty parliament

Democratic constitution Division of power between executive, legislature and judiciary

Secular state

Christian freedom of religion

SURFACE AREA: Windhoek CAPITAL: 90%

MAIN PRIVATE SECTORS: Mining, Manufacturing, Fishing and Agriculture 46%

BIGGEST EMPLOYER: Agriculture

FASTEST-GROWING SECTOR: Information Communication Industry

Diamonds, uranium, copper, lead, zinc, magnesium, cadmium, arsenic, pyrites, silver, gold, lithium minerals, dimension stones (granite, marble, blue sodalite) and many semiprecious stones

CURRENCY:

The Namibian Dollar (N$) is fixed to and on par with the SA Rand. The South African Rand is also legal tender.

Foreign currency, international Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Diners Club credit cards are accepted.

TAX AND CUSTOMS

All goods and services are priced to include value-added tax of 15%. Visitors may reclaim VAT.

ENQUIRIES: Namibia Revenue Agency (NamRA) Tel (+264) 61 209 2259 in Windhoek

Public transport is NOT available to all tourist destinations in Namibia.

There are bus services from Windhoek to Swakopmund as well as Cape Town/Johannesburg/Vic Falls.

Namibia’s main railway line runs from the South African border, connecting Windhoek to Swakopmund in the west and Tsumeb in the north.

There is an extensive network of international and regional flights from Windhoek and domestic charters to all destinations.

NATURE RESERVES: of surface area

ROADS:

HIGHEST MOUNTAIN: Brandberg

HARBOURS: Walvis Bay, Lüderitz

Spitzkoppe, Moltkeblick, Gamsberg

PERENNIAL RIVERS: Orange, Kunene, Okavango, Zambezi and Kwando/Linyanti/Chobe

EPHEMERAL RIVERS:

Numerous, including Fish, Kuiseb, Swakop and Ugab

20% 14 400 680

OTHER PROMINENT MOUNTAINS: vegetation zones species of trees

MAIN AIRPORTS: Hosea Kutako International Airport, Eros Airport

RAIL NETWORK:

TELECOMMUNICATIONS:

6.2 telephone lines per 100 inhabitants

MOBILE COMMUNICATION SYSTEM:

Direct-dialling facilities to 221 countries

GSM agreements with 150

species of lichen

LIVING FOSSIL PLANT: Welwitschia mirabilis

BIG GAME:

Elephant, lion, rhino, buffalo, cheetah, leopard, giraffe

20 antelope species

250 mammal species (14 endemic)

256 699

50 reptile species

ENDEMIC BIRDS including Herero Chat, Rockrunner, Damara Tern, Monteiro’s Hornbill and Dune Lark frog species

Most tap water is purified and safe to drink.

Visitors should exercise caution in rural areas.

0.4182 medical doctor per 1,000 people privately run hospitals in Windhoek with intensive-care units

4

Medical practitioners (world standard) 24-hour medical emergency services

3.1 million DENSITY: 3.8 per km²

461,000 inhabitants in Windhoek (15% of total) OFFICIAL LANGUAGE:

13 ethnic cultures 16 languages and dialects

LITERACY RATE: 1.8% POPULATION GROWTH RATE:

EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS: over 1,900 schools, various vocational and tertiary institutions bird species

GMT + 2 hours

220 volts AC, 50hz, with outlets for round three-pin type plugs

FOREIGN REPRESENTATION

More than 50 countries have Namibian consular or embassy representation in Windhoek.

PUBLISHING EDITORS

Elzanne McCulloch elzanne@venture.com.na

Gail Thomson gailsfelines@gmail.com

PRODUCTION

Liza Lottering liza@venture.com.na

LAYOUT & DESIGN

Richmond Ackah Jnr. design@venture.com.na

CUSTOMER SERVICE

Bonn Nortjé bonn@venture.com.na

PRINTERS

John Meinert Printing, Windhoek

The editorial content of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia is contributed by the Namibia Chamber of Environment, freelance journalists, employees of the Namibian Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) and NGOs. It does not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies held by MEFT or the publisher. No part of the magazine may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Conservation and the Environment in Namibia is published by Venture Publications Pty Ltd in Windhoek, Namibia www.venture.com.na Tel: +264 81 285 7450, 5 Conradie Street, Windhoek PO Box 21593, Windhoek, Namibia

That’s our mantra at Venture Media. Sharing stories, information and inspiration to an audience that understand and value why certain things matter. Why conservation, tourism, people & communities, businesses and ethics matter.

How these elements interrelate and how we can bring about change, contribute to the world and support each other. Whether for an entire nation, an industry, a community, or even just an individual.

We find, explore, discover, teach, showcase and share stories that matter.

www.venture.com.na or email us at info@venture.com.na for a curated proposal.

In 2021, we're focussing on telling and sharing STORIES THAT MATTER acros riou tal p urney and share your s wi ders ertain things matter

tion communities matter

w t elat ng about change, ute por er for an entire nation mun dividual

Each year, as we compile Conservation and the Environment in Namibia, I am reminded that conservation is as much about people as it is about nature. Behind every project, every set of data, every animal protected or tree replanted, there are individuals – scientists, community members, students, and rangers – driven by purpose and hope. They are the guardians of a changing world.

This year’s edition arrives at a critical moment. Namibia’s conservation landscape is evolving rapidly, facing pressures that are both old and new. From the fragile flow of the Okavango and the decline of our African Penguins, to the lesser-seen threats to woodlands and nearendemic plants, the stories in these pages reveal the complexity of protecting what we hold dear. They also reflect innovation and courage: communities coexisting with elephants, scientists gathering long-term plant and carbon data to guide future policy, and creative solutions to the challenges of human–wildlife conflict.

The truth is that conservation is no longer just about saving species; it’s about sustaining systems. It’s about understanding that an elephant herd in Kunene, a pangolin in Nyae Nyae, and a waterway in Kavango are all part of the same lifeline. It’s about acknowledging that the health of our environment defines our own well-being as Namibians.

Amid uncertainty, there is also resilience. Across the country, new generations of conservationists are emerging – young Namibians who see science and stewardship not as opposing worlds but as shared responsibilities. They are equipped with knowledge, technology, and passion, and they remind us that hope is an active choice.

As publishers, our role is to ensure that these stories continue to be told, that truth is amplified, and that collective awareness translates into action. Because only when we understand why something matters, do we truly begin to protect it.

Thank you to every contributor, researcher, and organisation featured in this issue, and to our readers, who continue to champion stories that matter. Together, we keep the conversation alive, and with it, the vision of a future where people and planet thrive side by side.

Yours in conservation,

Elzanne McCulloch

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is a membership-based and -driven umbrella organisation established as a voluntary association under Namibian Common Law to support and promote the interests of the environmental NGO sector and its work. The Members constitute the Council – the highest decision-making organ of the NCE. The Council elects Members to the Executive Committee at an AGM to oversee and give strategic direction to the work of the NCE Secretariat. The Secretariat (staff) of the NCE comprise a CEO and Office Manager. Only the Office Manager is employed full-time. The NCE currently has 67 Full Members – Namibian registered NGOs whose main business, or a significant portion of whose business, comprises involvement in and promotion of environmental matters in Namibia; and 13 Associate Members – individuals running environmental programmes and non-Namibian NGOs likewise involved in local to national environmental matters in Namibia. A list of Members follows. For more information on each Member, their contact details and website link, please go to the NCE website at www.n-c-e.org/members.

THE NCE HAS FOUR ASPIRATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND FIVE OPERATIONAL OBJECTIVES AS FOLLOWS:

Aspirational Objectives

• Conserve the natural environment

• Protect indigenous biodiversity and endangered species

• Promote best environmental practices

• Support efforts to prevent and reduce environmental degradation and pollution

Operational Objectives

• Represent the environmental interests of Members

• Act as a consultative forum for Members

• Engage with policy- and lawmakers to improve environmental policy and its implementation

• Build environmental skills in young Namibians

• Support and advise Members on environmental matters and facilitate access to environmental information

The NCE espouses the following key values:

• To uphold the fundamental rights and freedoms entrenched in Namibia’s Constitution and laws, including the principles of sustainable use, protection of biodiversity and inter-generational equity;

• To promote compliance with, uphold and share environmental best practice, recognising that the Earth’s resources are finite, and that human health and wellbeing are inextricably linked to environmental health;

• To recognise that environmental best practice is best promoted by implementing the following seven principles: sustainability, polluter pays, precautionary, equity, effectiveness and efficiency, human rights and participation;

• To develop skills, expertise and passion in young Namibians on environmental issues;

• To ensure political and ideological neutrality, be evidence-based and counter fake information; and

• To promote inclusiveness and to fiercely and fearlessly reject any form of discrimination.

TO EFFECTIVELY IMPLEMENT THESE OBJECTIVES AND VALUES, THE NCE HAS DEVELOPED EIGHT STRATEGIC PROGRAMME AREAS:

1. Support to Members

The NCE provides office facilities, boardroom, internet and safe parking for its out-of-town Members when in Windhoek. In partnership with EcoWings Namibia and FlyNamibia / Westair, two Cessna 182s and a Piper Cub are available for conservation purposes such as aerial surveys, radio-tracking and anti-poaching work. Our three 4x4 Toyota Hilux double-cab vehicles have become too costly to maintain. They have been sold and in early 2025, a new 4x4 will be purchased for use by Members for their conservation work; registration and research permit facilitation; and any other support requested by Members.

2. National facilitation

The NCE organises symposia and workshops on topical and priority issues; supports the development of strategic Best Practice Guides at sector level, the first on mining, the second (in preparation) reviews policy and legislation on and/or impacting Namibia’s environment; facilitates collaboration on conservation assessments and action plans, the latest being Namibia’s Carnivore Red Data Book (http://the-eis.com/ elibrary/search/27193); and representing the sector and Members on national bodies.

3. Environmental information

The NCE hosts and supports the development of Namibia’s Environmental Information Service (EIS at www.the-eis.com) in partnership with Paratus Telecom, a one-stop-shop for all environmental information on Namibia. The EIS comprises an e-library with over 30,435 reports, publications, maps, data sets, theses, etc., which are searchable and down-loadable. Included are all Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports since 2020 (over 5,700), over 800 wildlife survey reports and counts (some going back to 1926), and wildlife crime reports (over 4,000). It provides an Atlasing platform for citizen science data collection that currently covers mammals, reptiles, amphibians, butterflies, plants (both indigenous and invasive alien) and archaeology. Records are conveniently entered via a free cell phone App.

The NCE has also established a free, open access scientific e-journal – Namibian Journal of Environment – now in its ninth year (www. nje.org.na). The NCE and Venture Media’s environmental website “Conservation Namibia” (www.conservationnamibia.com) tells Namibia’s conservation stories via blogs, factsheets, video and articles from this magazine. The NCE informs the public on topical environmental issues on its website (www.n-c-e.org), Facebook page, X (Twitter) feed and LinkedIN profile. The Namibian Environment and Wildlife Society (NEWS) with support from the NCE recently launched a new tool to help stakeholders and the public better engage with EIAs – the EIA Tracker (https://eia-tracker.org.na/), a transparent, user-friendly system that presents and maintains information on all

development projects that require EIAs, with a current database of 2,298 proposed and existing projects.

The NCE addresses national threats to Namibia’s environment and natural resources by first attempting to work constructively with the relevant government or other entity but, if necessary, through public exposure. The NCE has addressed the issue of Chinese incentivised poaching and illegal trade in specially protected wildlife, the overfishing of pilchards in Namibian waters, illegal and unsustainable timber harvesting and export, and the need to reduce and eliminate single-use plastic from Namibia’s environment.

In 2024, it published a position paper on the proposed hydrogen developments for the Tsau ||Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park, explaining that this product is correctly termed red hydrogen due to the major potential impacts on biodiversity (https://n-c-e.org/ wp-content/uploads/Green-hydrogen-Tsau-Khaeb-National-ParkNCE-Position-Paper.pdf). This year, NCE produced a series of films showcasing Namibia’s Wildlife Economy – including a 7-minute teaser, a 36-minute full film, and 11 interviews of varying lengths featuring MEFT, community leaders, hunters and game ranchers, and non-government conservation organisations. The purpose of this film is to help people who are not familiar with the concept of the wildlife economy and the role of hunting in conservation –especially Western policy-makers and decision-makers – to be better informed on this issue and reduce their pressure on Namibia and its neighbouring countries for taking this approach to conservation. The NCE also produced an opinion on the in-situ leach uranium mining in the transboundary Stampriet aquifer in the Kalahari. Our position is simple – you don’t pollute and contaminate one of our most important groundwater resources for years and decades for short-term uranium mining benefits. This would put at risk the entire economy of the Kalahari, and many sectors beyond this aquifer (https:// conservationnamibia.com/blog/uranium-leach-mining.php).

It has also initiated a highly successful pangolin reward scheme in partnership with MEFT, some NCE Members and communities. The scheme rewards people for providing information on pangolin trafficking leading to arrests – more than 300 criminal cases opened and over 500 people arrested and charged.

5. Environmental policy research

When we talk about the “environment” we mean the interrelationship of ecological, social and economic aspects – essentially sustainable development. This is appropriate for a country with an economy reliant mainly on natural resource-based primary production where ecological and socio-economic issues are two sides of the same coin. However, this conceptual approach is rarely understood by people from western industrialised countries who think of environment as being just the green environment. To get around this problem, the NCE has established a socio-economic / livelihoods component that works seamlessly with the environmental component and focusses mainly on the urban environment. Over 50% of Namibians now live in towns and the city of Windhoek, with a projected rise to 70% by 2030. The priority areas of focus are access to affordable urban land for housing, appropriate sanitation, solid waste management, energy and research on the economics of poverty.

6. Young Namibian training and mentorship

Over the past eight academic years (2018-2025) the NCE in partnership with Woodtiger Fund has provided 270 post-graduate bursaries in the broad environmental field (including subjects such as biodiversity conservation, natural resources management, wildlife and tourism management, sustainable agriculture, water, forestry and fisheries management, climate change mitigation and adaptation, renewable energy, data and spatial science, risk and change management, leadership, through to environmental economics, environmental law, environmental engineering) and 52 internships, mainly for NCE bursaryholders, that involves close mentoring by experienced environmental professionals. The aim is to build the capacity and confidence of young Namibians to become the environmental leaders of tomorrow.

In 2024, NCE supported the establishment of the Namibian Youth Chamber of Environment, which seeks to inspire and equip young (18-35 years) Namibians with the confidence and skills to advocate for the environment during their studies, within their communities and in their professional settings. NYCE was formally established during their first AGM held in June 2024. They are active on social media, using Instagram, TikTok and WhatsApp to reach young people interested in the environment across the country. Current membership stands at 335 individuals and eight youth organisations, with members from all 14 regions of Namibia. This year, NYCE held a successful Arbour Day in collaboration with the Schools Environmental Clubs of Namibia to get scholars and students involved in tree planting and to learn more about Namibia’s indigenous plants. They also hold regular clean-up campaigns, webinars, and quizzes to keep their membership engaged and inspired.

7. Fund raising

Core funding for the NCE is currently provided by B2Gold. This means that all additional funding received is invested directly into environmental projects and programmes – there are no overhead costs. The NCE focuses on corporate support and avoids targeting funding sources that may compete with its Members. The corporate sector assists with fund raising by approaching their clients, partners and networks. Our main sponsors are shown on the back cover.

Funds raised by the NCE are used strategically to support priority environmental projects and programmes in Namibia. Emphasis is placed on legacy initiatives that have tangible outcomes. These are often based on national policy and bring together government and NGO partners, communities and the private sector, and frequently lead to investments by larger bilateral or multi-lateral funding organisations. An on-line grant application process allows NCE Members to apply for funding. To date 229 grants have been awarded, to the value of just under N$ 32 million, with 90% going to NCE Members. Some of these projects are showcased in this magazine.

A. Speiser Environmental Consultants cc

African Conservation Services cc

Africat Foundation

Ameib Scientific Station

Anchor Environmental Consultants (Pty) Ltd

Ashby Associates cc

Biodiversity Research Centre, NUST (BRC-NUST)

Botanical Society of Namibia

Brown Hyena Research Project Trust Fund

Bwabwata Living Museum

Canyon Nature Trust

Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF)

Conservancy Association of Namibia (CANAM)

Desert Lion Conservation Trust

Development Workshop Namibia (DWN)

Environmental Assessment Professionals Association of Namibia (EAPAN)

Earthlife Namibia

Eco Awards Namibia

Eco-logic Environmental Management Consultancy cc

EduVentures

Elephant Human Relations Aid (EHRA)

Environmental Compliance Consulting (ECC)

EnviroScience

Felines Communication and Conservation Consultants cc

Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF)

Gobabeb Research and Training Centre

Greenspace

Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC)

JARO Consultancy

Kwando Carnivore Project

LM Environmental Consultants

Museums Association of Namibia

N/a’an ku sê Foundation

Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO)

Namib Desert Environmental Education Trust (NaDEET)

Namibia Archaeological Trust

Namibia Biomass Industry Group (N-BiG)

Namibia Bird Club

Namibia Nature Foundation (NNF)

Namibia Professional Hunting Association (NAPHA)

Namibia Scientific Society (NSS)

Namibian Environment and Wildlife Society (NEWS)

Namibian Hydrogeological Association

NamibRand Nature Reserve

Namibian Beekeeping Association

Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN)

Ocean Conservation Namibia

Omba Arts Trust

Ongava Game Reserve / Research Centre

Orange River-Karoo Conservation Area (ORKCA)

Otjikoto Trust

Pangolin Conservation and Research Foundation

ProNamib Nature Reserve

Progress Namibia TAS cc

Rare and Endangered Species Trust (REST)

Research and Information Services of Namibia (RAISON)

Rooikat Trust

Save The Rhino Trust (SRT)

Scientific Society Swakopmund

Seeis Conservancy

SLR Environmental Consulting

Southern African Institute of Environmental Assessment (SAIEA)

SunCycles Namibia

Sustainable Solutions Trust

Tourism Supporting Conservation Trust (TOSCO)

Twin Hills Trust

Venture Media

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS

Bell, Maria A

Black-footed Cat Research Project Namibia

Bockmühl, Frank

Desert Elephant Conservation

Irish, Dr John

Kolberg, Herta

Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research

Lukubwe, Dr Michael S

Namibia Animal Rehabilitation, Research and Education Centre (NARREC)

Seabirds and Marine Ecosystems Programme

Sea Search Research and Conservation (Namibia Dolphin Project)

Strohbach, Dr Ben

Wild Bird Rescue

Namibia is in desperate need of truly sustainable development. Even using a very broad definition of “employed” (if you have worked at least one hour in the past week), our unemployment rate sits at an unacceptably high 55%, and a shocking 61% among young Namibians. All sectors of the country should be seized with addressing this issue, including the environmental sector. Yet the particular responsibility of our sector is to ensure that development is sustainable and thereby benefits future generations of Namibians as well as those alive today.

NCE’s stance on various development projects proposed during recent years reflects this responsibility. We support projects and ideas that have strong potential for creating economic growth and jobs with environmental impacts that are well-understood and can be mitigated through responsible management. Among these are responsible mining, including marine phosphate dredging, and the developing offshore oil and gas sector.

We do not support projects that produce relatively few jobs or economic benefits in relation to their environmental impacts. Examples of these are poorly managed mining operations in areas that are better suited for high-value tourism, in situ leach mining using the Stampriet Aquifer, exploring for oil and gas in the Okavango ecosystem, and developing hydrogen projects in the Tsau ||Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park. Each project is assessed on its merits, taking into consideration the costs, benefits, risks and location, among other factors.

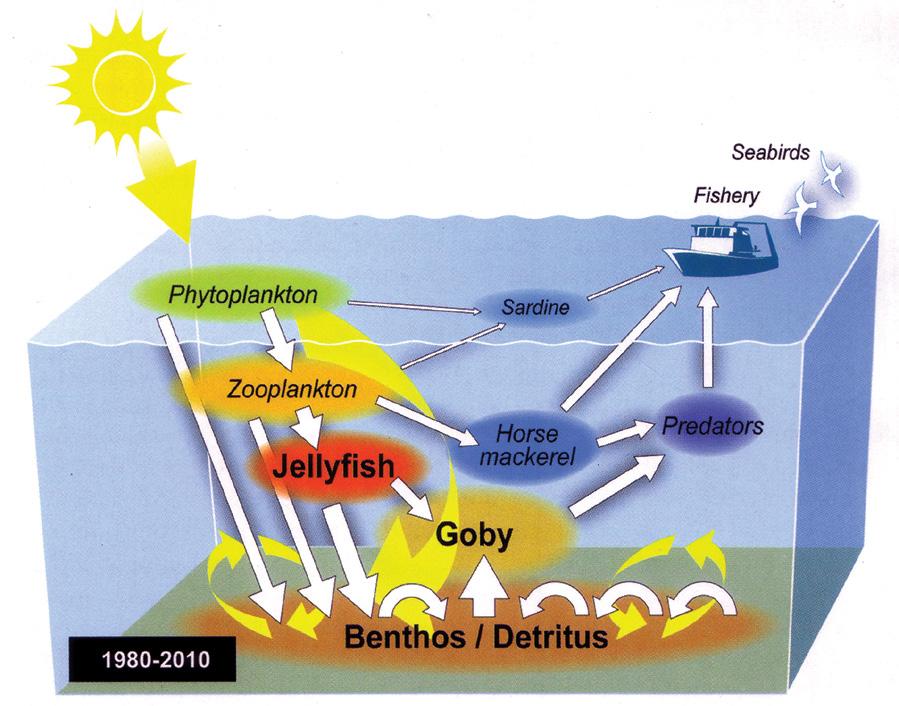

Namibia’s possible development pathways should be assessed at the national scale with an eye on global developments and our future. Each development project within a sector should therefore be evaluated in terms of its contributions to these larger outcomes. We take this approach to assessing Namibia’s energy sector, which is on the cusp of major change. Which energy options will deliver the maximum benefits and jobs for as many Namibians as possible, both today and in the future? Turn to p.74 to find out.

Wherever possible, we work with government to promote sustainable development initiatives, such as our recent film showcasing the wildlife economy. Yet it remains our responsibility as a Chamber to ring the alarm bells and stand against unsustainable development options whenever they are proposed.

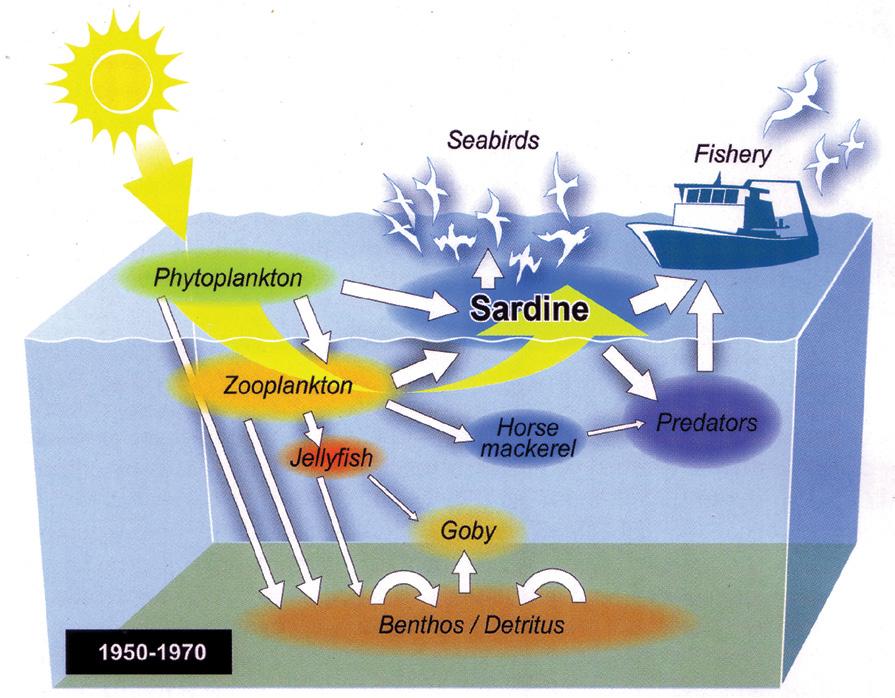

Several articles in this year’s magazine tackle development-related challenges. In the ocean, the fisheries industry and marine biodiversity are suffering the consequences of corruption and unsustainable fishing quotas and practices over the last few decades (pp.40 and 71). Moving inland, the Okavango River system could collapse if nothing is done about unsustainable water use and development in the catchment areas and along its banks in Angola and Namibia, which would result in economic collapse for Botswana’s tourism sector (p.24).

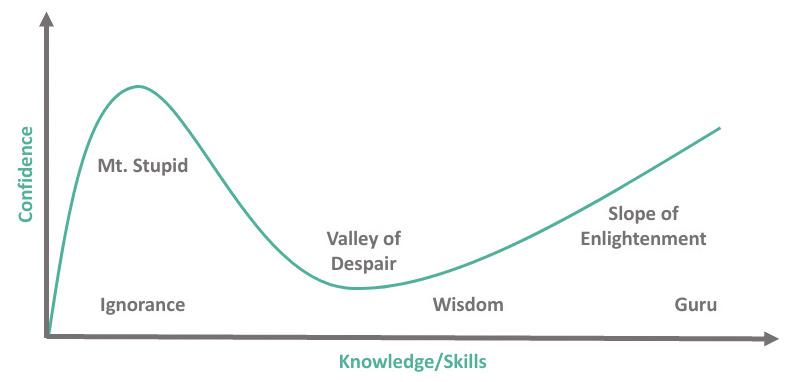

Another important element of sound decision-making for sustainable development is science – collecting long-term, reliable data and analysing it to answer our most pressing questions is indispensable. On page 60 Prof. Morgan Hauptfleisch explains how science moves us away from arrogance with little knowledge towards a place of uncertainty with more knowledge, until we finally gain real understanding of complex socio-ecological issues.

Dedicated plant researchers (showcased on pp.18 and 50) are contributing valuable information to this cause. Science has led the way to a new classification system for giraffe (p.30), alerting the world to the dangers of lead bullets (p.44), and recording amazing hyaena behaviour (p.14). Combining scientific methods and local knowledge makes even greater gains for conservation, as illustrated for elephant conservation in communal conservancies (pp.10 and 56) and Namibia’s overall approach to community conservation (pp.36 and 66). In this regard, we support two very important platforms that make good quality information available to everyone free of charge. These are the Environmental Information Service (EIS) at www.the-eis.com and Conservation Namibia at conservationnamibia.com on which all the articles in this magazine are published to make them internationally available.

As you dive into the stories told by NCE members in this year’s edition, maintain a sustainable development perspective, noting how the environmental sector can contribute to Namibia’s prosperity, both now and for generations to come.

Yours in Conservation,

Chris Brown and Gail Thomson

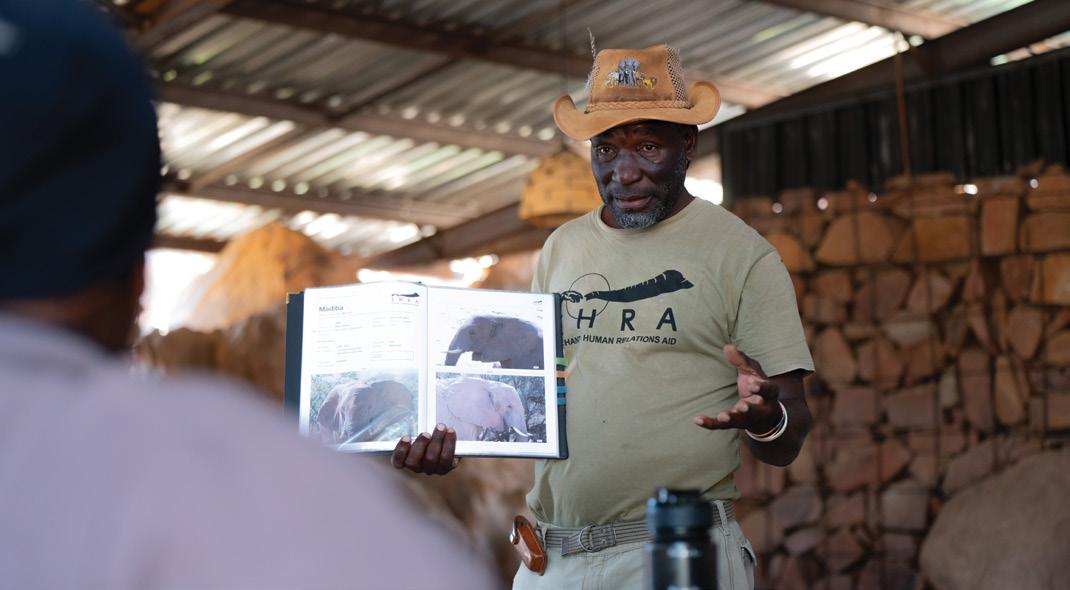

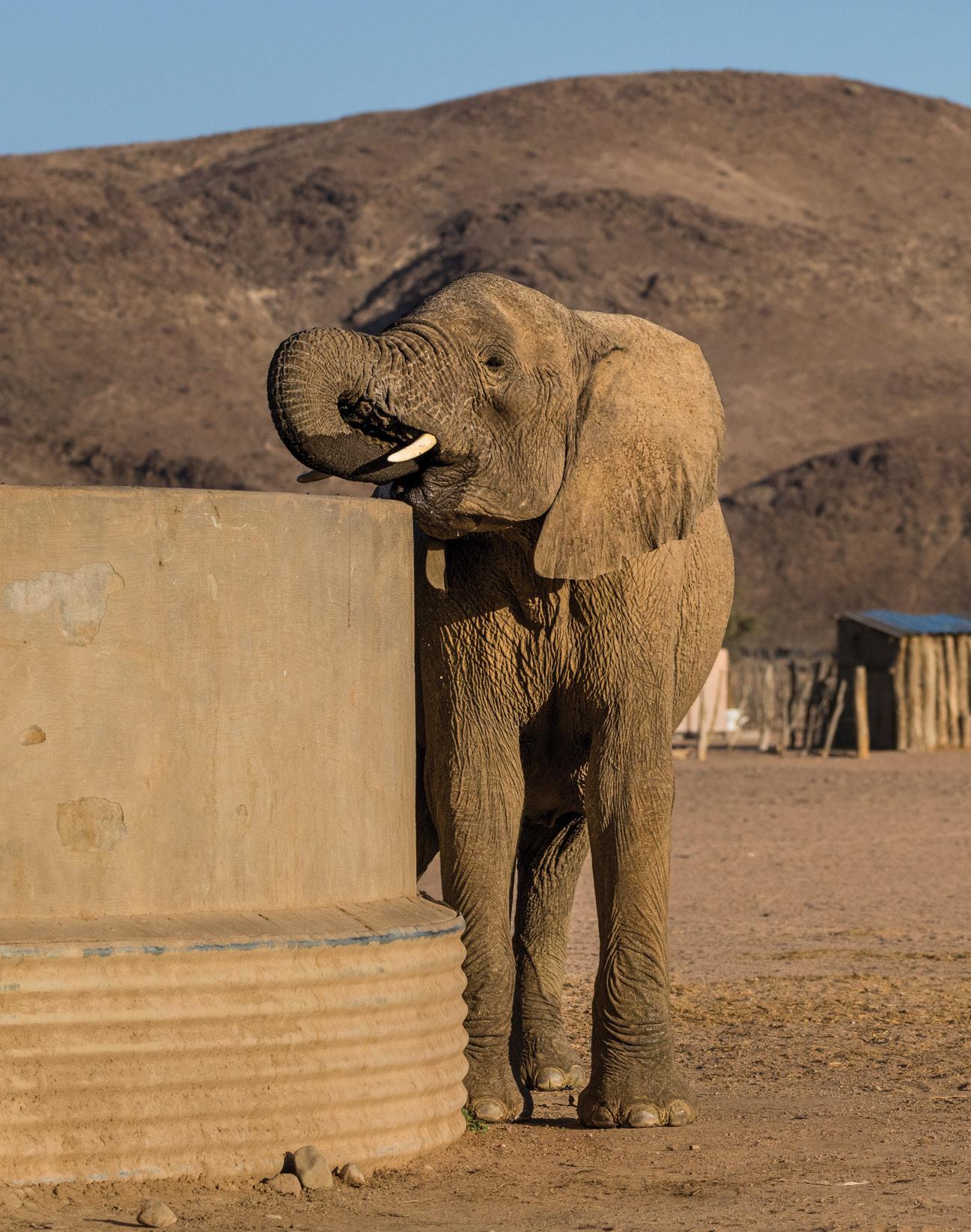

How Community Elephant Guards are working towards coexistence

Text and photos by: Elephant Human Relations Aid (EHRA)

Since 2003, Elephant-Human Relations Aid (EHRA) has been dedicated to implementing holistic solutions for human-elephant conflicts in Namibia’s northwest. We assess the diverse ways that free-roaming elephants negatively impact people’s lives and livelihoods, and trial and apply effective measures to foster peaceful coexistence. The ultimate aim is to safeguard elephant survival beyond national park boundaries by employing strategies centred on harmonious living and habitat protection.

EHRA launched the Elephant Guard Programme in 2019 as a boots-on-the-ground extension of its longstanding conflict prevention work, providing regular outreach, safety education, and rapid response to communities experiencing human-elephant conflict. The Community Elephant Guards are local people – respected members of their villages and conservancies – carefully chosen by traditional leaders or conservancy committees. This ensures deep trust and cultural alignment. Before taking on their vital roles, each Guard undergoes a long and rigorous training programme, which they must pass to be certified. This training equips them with the knowledge, skills, and confidence to respond effectively to complex situations involving elephants.

Although the programme paused during COVID-19 due to funding constraints, it was revived in 2022 and is now active in Sorris Sorris Conservancy, the greater Omatjete area, and around Fransfontein town. Five trained Community Elephant Guards work around the clock in these elephant conflict hotspots – including one outstanding female Guard who is breaking barriers and inspiring other women.

Human-elephant conflict is one of the main drivers of elephant population decline in northwest Namibia, and at the heart of this conflict lies fear and misunderstanding. EHRA’s educational PEACE Project (People and Elephants Amicably Co-Existing), launched in 2009, laid the foundation by training thousands of community members on how to safely interact with elephants and prevent conflict. The Elephant Guards now continue that legacy, becoming the trusted experts in their communities – first responders during emergencies, elephant educators, and compassionate listeners.

What is truly remarkable is how motivated these local communities are to take ownership of the situation themselves. Rather than outside actors stepping in, it is their own neighbours – people who share their daily lives and challenges – leading the way. This local leadership is transforming fear into agency, inspiring pride and proactive problem-solving.

The Elephant Guards’ daily work is as diverse as it is vital. One of their most important roles is providing live updates on collared elephant movements – a sort of elephant “weather app” that helps communities prepare for a visit. This real-time information, paired with in-person outreach, helps shift fear into empowerment.

When conflict occurs, the Guards are often the first to respond –day or night. They assess the damage, help with repairs, and offer immediate support. Equally important, they investigate the cause and recommend practical solutions, often using materials and knowledge already available within the community.

The numbers reflect their dedication. In the past year, Elephant Guards spent:

• 29.5% of their time on community outreach and training

• 20.6% responding to conflict and conducting repairs

• 16.6% attending community meetings to build trust

• 6.6% supporting Eco Clubs at schools

• 5.6% guarding homesteads and funerals during elephant activity

The remaining time was spent coordinating logistics, reporting data, and following up on prior incidents – work that often goes unseen but is essential to the programme’s success.

The results are tangible. As one villager, Mr. Sarob from Farm Arbeid, recalled: “I was walking with two friends when we bumped into elephants. They wanted to run, but I remembered what Taiwin [our Elephant Guard] had taught us – not to run, since there might be more elephants nearby. So, we climbed a hill instead. From there, we saw we were surrounded. That knowledge may have saved our lives.”

Types of elephant damages reported in the conservancies that EHRA works with

The Guards are often called in the middle of the night when elephants approach villages. Residents are scared – sometimes too scared to implement what they’ve been taught. In these moments, Guards like Taiwin, the Head Guard for the western region, calmly stay on the phone, guiding people step by step through how to safely move elephants away from homesteads.

Perhaps most empowering is how the Guards help communities find low-cost, high-impact solutions using what they already have. One popular tactic involves the use of honey bee sounds, which elephants naturally avoid. While real beehive fences aren’t always feasible in this dry part of the country, villagers now download the buzzing of angry bees from YouTube and play them through phones, speakers, or even televisions when elephants approach.

“They know elephants are smart,” says Taiwin. “So they download several different versions to keep them guessing. And it works!” Thanks to the Elephant Guards, many families who once lived in constant fear now feel secure and confident. With protected water tanks, solar pumps replacing diesel, gardens surrounded by electrified fencing, and a growing toolbox of conflict mitigation strategies, attitudes are shifting. People are not only more accepting of elephants – they’re starting to feel proud of them.

“I used to be terrified of elephants. I didn’t want them. Now, I feel safe and I understand. I can enjoy the elephants now,” says Geraldine from Farm Irene. “And when my grandchildren visit, I show them the elephants. I’m proud they are here.”

In a world where coexistence often feels like a dream, EHRA’s Elephant Guards are proving that with the right knowledge, local leadership, and compassion, it’s a reality worth working for.

“Their passion, creativity, and commitment are what make this programme truly special,” reflects Christin Winter, EHRA’s Conservation Programme Manager. “This small team dreams big – and they are making that dream work.”

By: Gail Thomson

Tivat, a female brown hyaena, was afraid of seals when she first encountered them. Over a few months, she learned to kill seal pups ‒ not unusual for a brown hyaena. Just one year after her first encounter with seals, Tivat did something that (to our knowledge) no other brown hyaena has achieved: she killed an adult Cape fur seal!

To understand this achievement, you need to know a little more about brown hyaenas. Every carnivore textbook will tell you that they are primarily scavengers, with only 6-16% of their meals coming from things they have killed. They are known to eat snakes, insects, and even fruits and vegetables!

The hyaenas living along the coastline of Namibia are renowned for killing seal pups, and probably hunt more than their inland relatives. Nonetheless, they prefer taking pups that are sleeping or not paying attention to their surroundings. The unsuspecting seal pup is quickly dispatched with a crushing bite to the head.

Dr Marie Lemerle of the Brown Hyena Research Project thought she had witnessed all of the brown hyaena’s hunting strategies, until Tivat showed up. “I’ve spent over 3,000 hours watching brown hyaenas foraging near seal colonies,” she says, “sometimes they pretend to be sleeping to get the pups to relax and forget that a predator is there; other times they dash into the colony and grab any pup that is too slow to get away.”

When Tivat first showed up at the Baker’s Bay seal colony south of Lüderitz, she was an unlikely candidate for pushing the boundaries of hyaena hunting abilities. “She was extremely skittish when we first spotted her in October 2023,” Lemerle recalls, “she even ran away from the seals!” The research team has since discovered that this hyaena most likely originates from an area without a seal colony, which explains her unusual nervousness.

In May 2024, after several months of visiting the seal colony, Tivat discovered what many other hyaenas had before her: seal pups are

quite easy to kill. By January 2025, she had become a prolific pup-killer, managing to take 12 of them in just over an hour of hunting.

Yet Tivat had already set her targets on bigger prey: “I was amazed to witness her trying to take down an adult female seal during October 2024, but unsurprised that her hunt was not successful.” After 90 seconds of struggling, the seal managed to escape. Dr Lemerle’s assumption that Tivat was being overly ambitious is based on her knowledge of the species and extensive personal observations.

Brown hyaenas have never before been recorded taking down prey larger than themselves. Hyaenas only weigh 50 kg maximum, while the average weight of a female Cape fur seal is 57 kg (the massive male seals weigh over 240 kg). Only lions are known to successfully hunt adult Cape fur seals from the land, as recorded by Dr Philip Stander on the Skeleton Coast. Lions are way above brown hyaenas in the predator pecking order, so surely Tivat’s dream of killing an adult seal was unrealistic?

That assumption was shattered on 9 July 2025. Lemerle and Natacha Anglade (a Master of Science student) spent the whole day at Baker’s Bay seal colony, watching from different vantage points. Their patience paid off, as they witnessed something that no scientist had before.

Tivat arrived at the colony in mid-morning and started creating havoc among the seals. She ran up to each group of seals in turn, causing most of them to flee into the sea. Sometimes, the seals would charge back at her, ‘knowing’ that they are too big for a brown hyaena to subdue. One struggle lasted only three seconds before the seal freed itself from the hyaena’s grip.

Tivat was undaunted and tried her luck with four seals that day. Her fourth attempt earned her the ultimate prize. The final victim initially lunged at Tivat, but it seems that the hyaena had learned how to fight during the previous struggles and latched onto the seal’s neck. “We filmed the battle from our distant observation points, but we knew it would soon be over when blood spurted from the seal’s carotid vein,” Lemerle remembers this brutal, fascinating scene

clearly. It took about eight minutes from the first attack to the seal’s last breath.

As it turns out, this incredible feat wasn’t a once-off event. Tivat has since killed at least one more adult seal, and the researchers noted that the most recent kill was highly efficient. “It seems like she is specialising in taking adult seals due to the lack of pups in the colony at this time,” observes Lemerle, “it will be interesting to see if other hyaenas will learn her hunting tactics.”

To learn more about this remarkable hyaena, the Brown Hyena Research Project fitted Tivat with a GPS collar in August 2025. “While we were collaring her, we estimated her age at 10-12 years old, and she weighed 43 kg, making her seal-hunting feats even more impressive!” Lemerle and the research team hope to learn more about Tivat and her clan. Since brown hyaenas from the same clan often forage separately, it is challenging to determine which clan they belong to solely by observing their hunts. With GPS data, the researchers are likely to find the clan’s den where they raise their cubs, and thus identify Tivat’s clan mates.

This discovery demonstrates the value of long-term observational research, where scientists simply watch their subjects and record their behaviour. It also shows what we can learn when animals are not disturbed by human presence. These brown hyaenas inhabit the Tsau ǁKhaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park, which is off-limits to all but a select few researchers and permit-holding visitors. The researchers watch the hyaenas from a distance to ensure that their presence isn’t influencing the hyaena or seal behaviour.

As Tsau ǁKhaeb opens to the public with plans for tourism, the impacts on the animals that have lived with minimal human presence need to be minimised as much as possible. This is possible with well-managed tourism, says Lemerle: “If there are a limited number of vehicles operating in the area, we can work with them to establish best practices for viewing hyaenas and seals.” Rule-breakers are relatively easy to identify and report when there are few of them.

If the Park is opened up for industrial development, however, such rules and regulations are likely to be trampled, along with the unique plants found here. The plans to produce hydrogen in this area include large industrial plants, solar panels, wind turbines, pipelines, roads, and pylons. With so many people involved in the construction and maintenance of such infrastructure, it will be impossible to limit their disturbance of wild animals, not to mention the plethora of other impacts of this ill-conceived idea.

While concerns about the future of Tsau ǁKhaeb National Park remain in the background, the hyaena researchers will continue to study this resilient and adaptable carnivore. Tivat may even be a pioneer of new hyaena behaviour if others start copying her methods. Follow the Brown Hyaena Research Project on Facebook for future updates about Tivat and insights into the lives of these remarkable coastal carnivores.

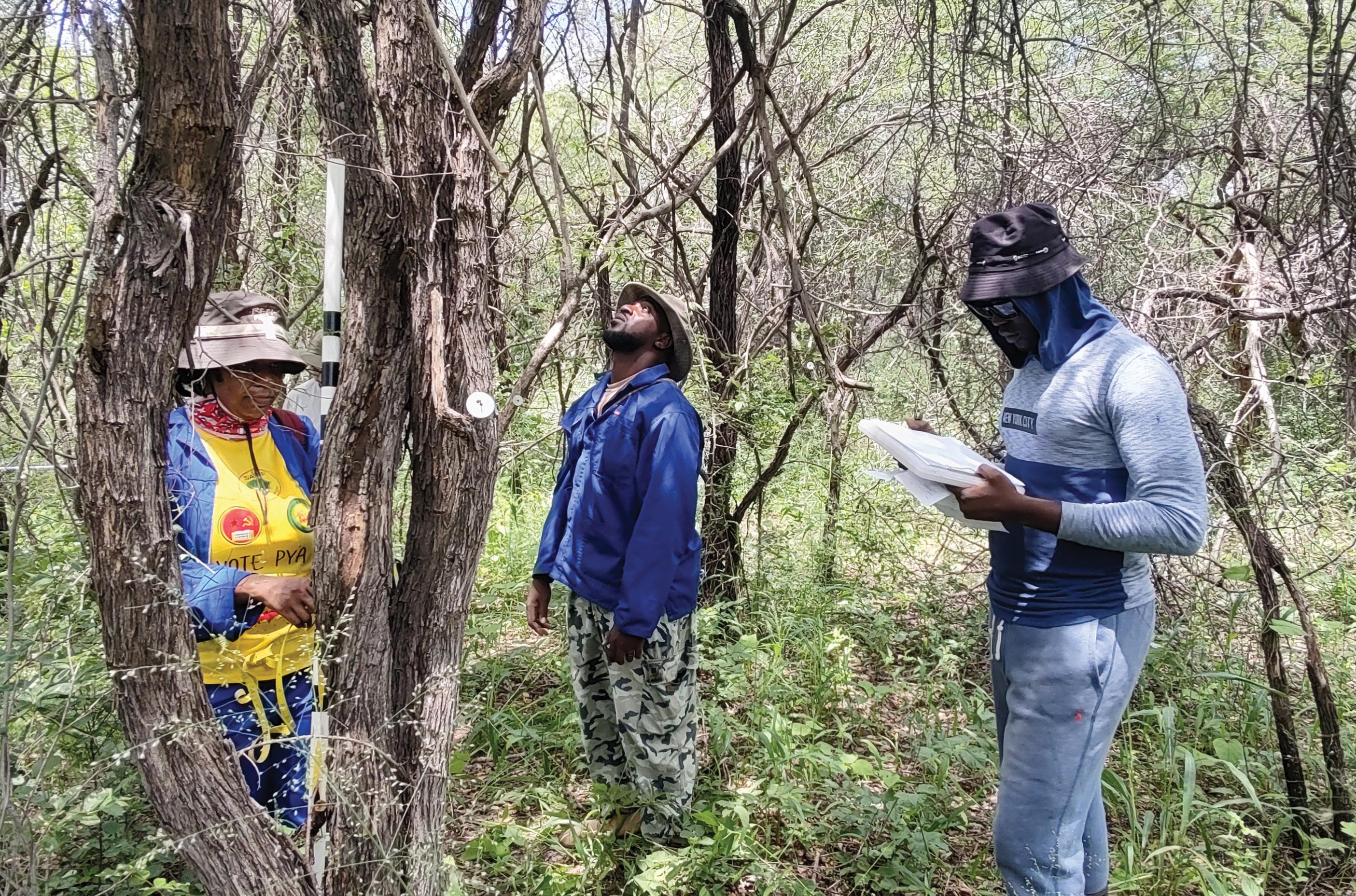

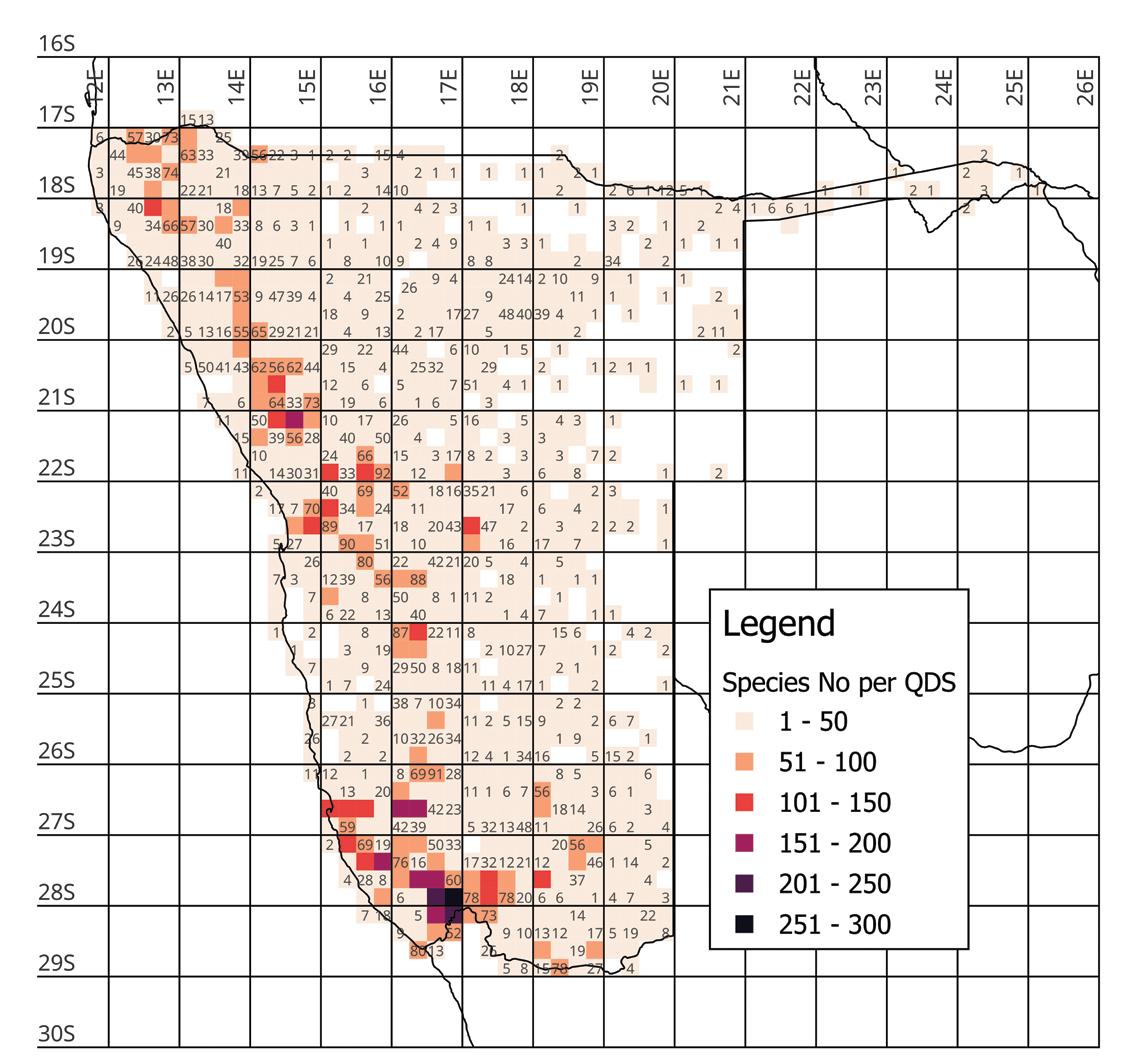

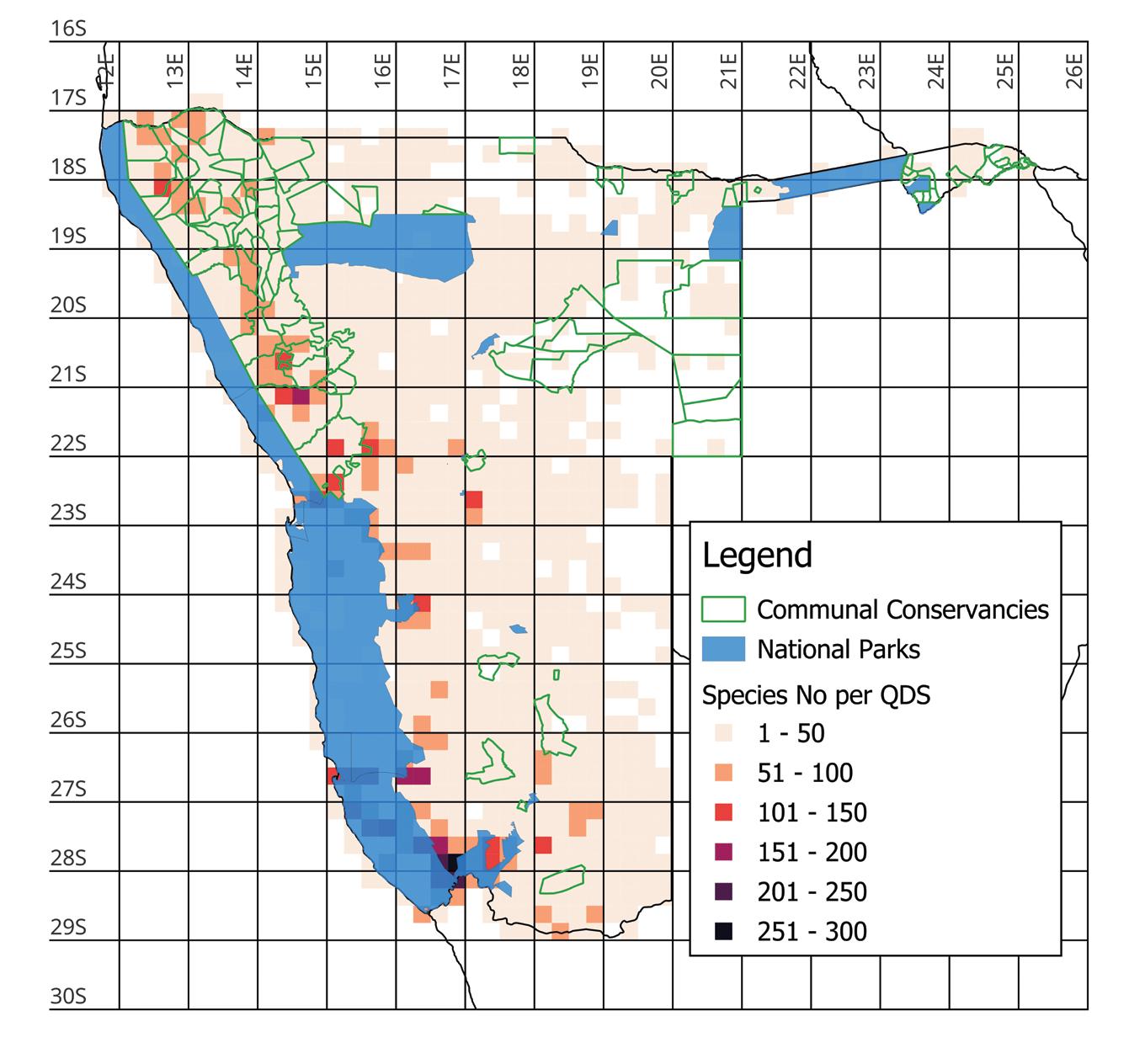

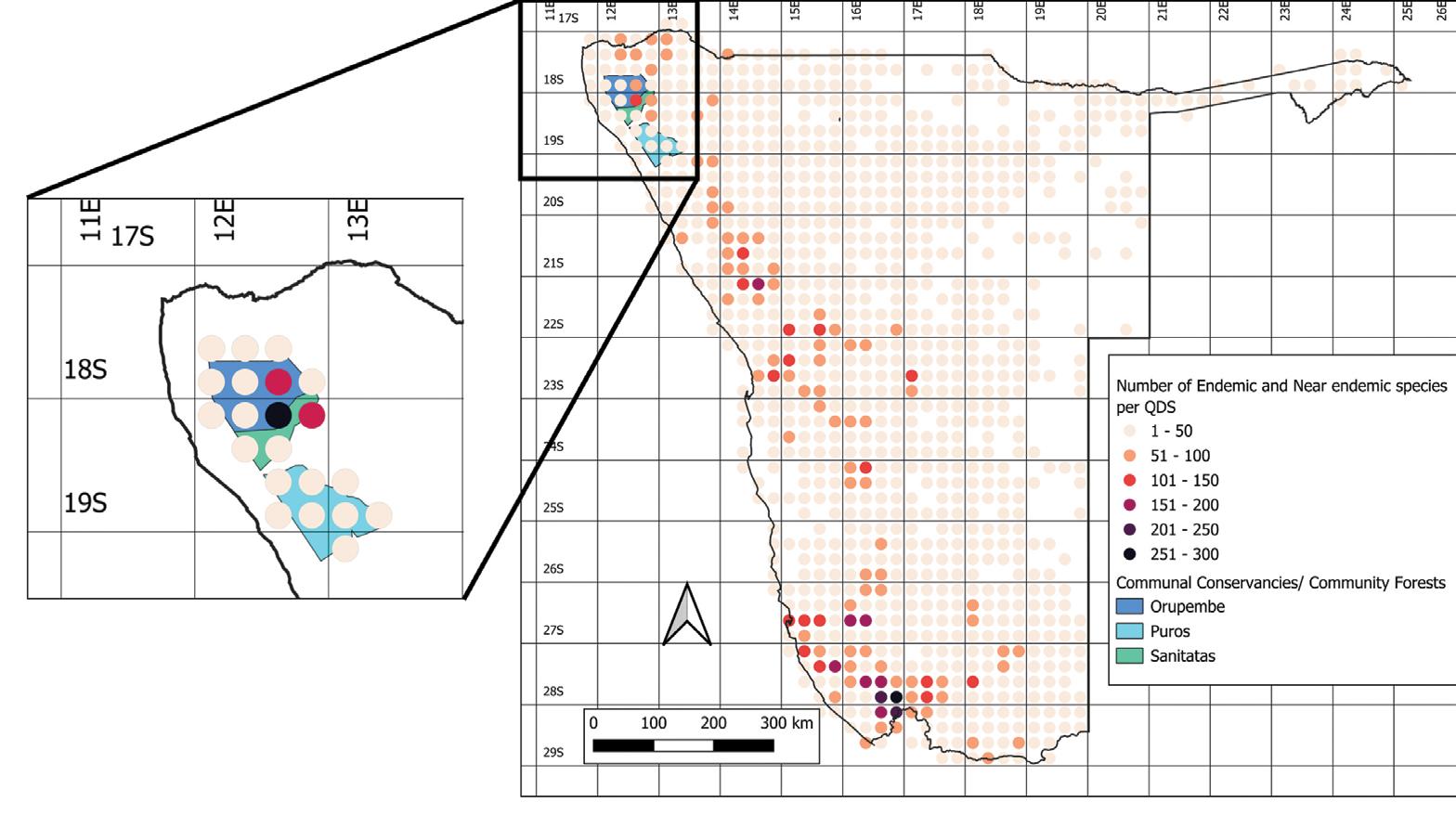

By: Alice Jones, Leena Naftal, Hermane Diesse, Gabriel Uusiku, John Godlee, Kyle Dexter and Vera De Cauwer

Vimbai Rukuni, George Lyanabu and Hermane Diesse during the resurvey of our plots at Sachinga Livestock Centre, Zambezi

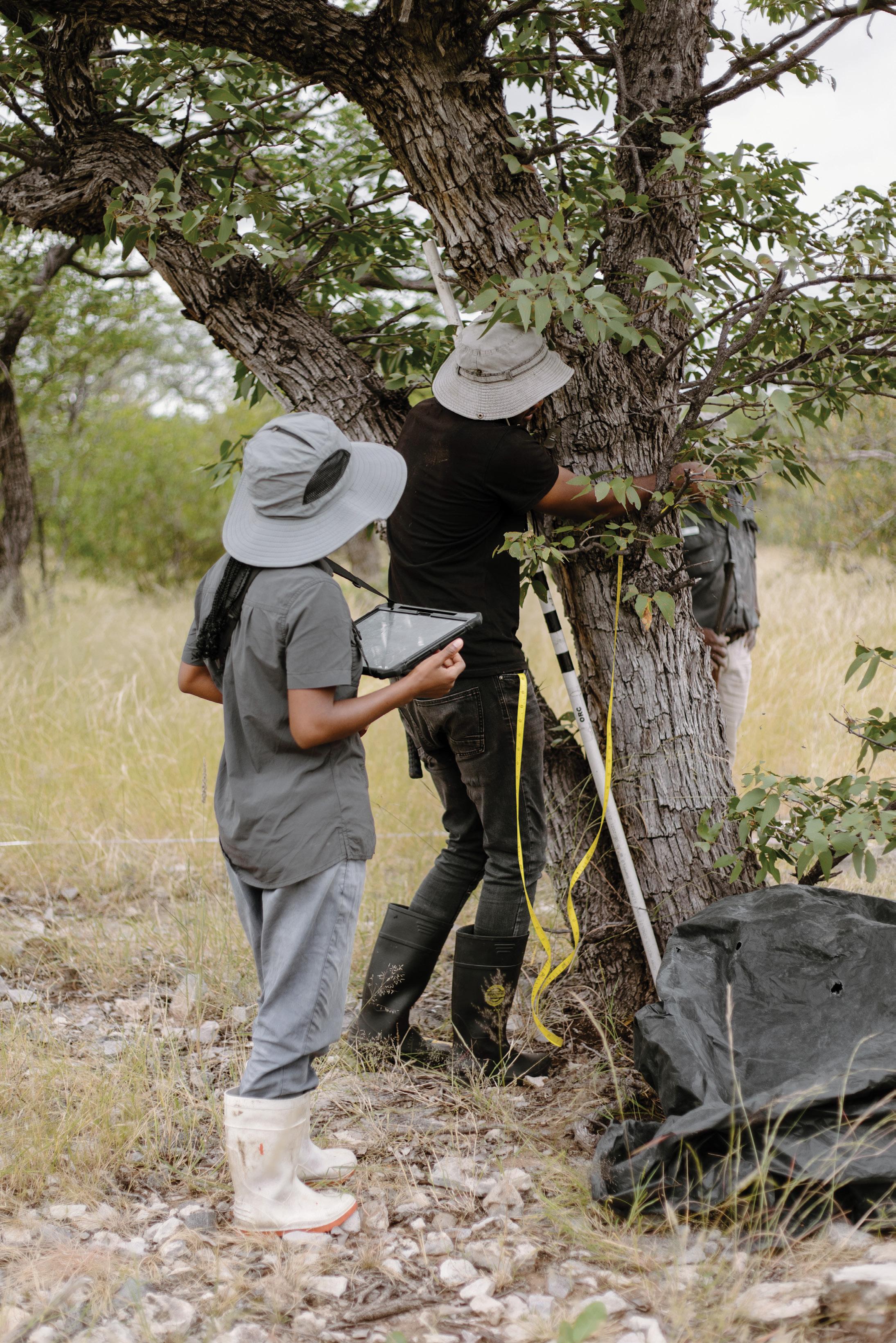

Across the grasslands and woodlands of Africa, a network of researchers is collecting long-term, highly detailed data on plants and their environments. This effort fills significant gaps in our understanding of how woodland savanna ecosystems function and respond to direct human impacts and climate change.

Professors and students at the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST) Biodiversity Research Centre have joined colleagues from international universities in this new network. One of the main tools they are using to better understand woodlands is called a Permanent Sampling Plot (hereafter, ‘plot’), which is a one-hectare block of land that supports a representative sample of vegetation. After they are identified and marked, the researchers can return to these plots every few years to re-record detailed information on the plants within them. This data is used to monitor the species present, their size, and how these characteristics change over time.

Each plot is carefully selected to capture the diversity of the landscape, taking into account vegetation cover, species composition, elevation, soil type, and land-use history. While the plots must be accessible, we typically select areas that are unlikely to be disturbed by humans, allowing us to understand natural processes and apply these insights to other natural areas. We also explore how people interact with the land by establishing plots in areas grazed by cattle or adjacent to farmland. This work is always done in collaboration with landowners and local residents to ensure long-term access to these valuable sites.

The only indication that a piece of land is within one of our research plots is the presence of four permanent corner markers and the small metal tags fixed to the tree trunks. Each tag has a unique number, allowing us to track each tree over time. The plot corners serve as

anchors from which we run 100-metre measuring tapes to define our plot borders each time we visit. These permanent markers must be unobtrusive yet sturdy enough to withstand the attention of inquisitive elephants and baboons.

In Namibia, we have marked 23 plots at four sites, with most of them established in 2023. Three plots established by NUST in 2006 were re-established. Two of our sites are located in State Forests (Kanovlei in Otjozondjupa and Hamoye in Kavango East), one is in a private protected area (Ongava Private Game Reserve in Kunene), and the fourth is situated within the Sachinga Livestock Centre in Zambezi. Each of these sites hosts woodlands that are dominated by different tree species, allowing us to compare these ecosystems.

The value of long-term, detailed studies on Namibian woodlands is multiplied when we add our data to the network of similar sites across southern Africa. Our plots are part of the Socio-Ecological Observatory for the Southern African Woodlands (SEOSAW), which was established to help researchers standardise their plot marking and research methods across the region.

As we conduct our studies in Namibia, our colleagues are doing similar studies on plots in other countries. When we combine our data and knowledge through SEOSAW, we can look for long-term, widespread trends and features of African woodlands that would go unnoticed if each study group focused solely on its own country. The overarching aim of SEOSAW is to understand how these dynamic ecosystems are changing and how this influences biodiversity, carbon storage, and local livelihoods.

What kinds of data do we collect when we visit our plots? This depends to some extent on which studies we are currently

undertaking and the standard data collection protocol established for the long-term SEOSAW monitoring work. During most visits, we measure mature trees by recording stem diameters and noting signs of mortality or resprouting. We may also estimate the percentage cover and biomass of grasses, forbs (leafy plants that are not trees or shrubs), leaf litter, and woody debris. Each researcher in our team has their own projects that will either utilise these measurements or incorporate additional data to answer their respective research questions.

For Alice Jones, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, data from these long-term plots are the foundation of her doctoral research into savanna tree recruitment strategies. Using species composition data collected from the mature tree surveys, she investigates whether the trees we see today are successfully reproducing to maintain stable populations. During visits to the plots, she systematically samples the soil seed bank and seedling layers. By identifying and counting the species present in these early life stages, Alice can trace recruitment patterns and pinpoint potential bottlenecks in regeneration. Her work sheds light on the long-term stability of tree populations, which is vital for understanding the future of savanna ecosystems and guiding conservation efforts.

Leena Naftal, a PhD student at NUST, is using the tree measurements and information from soil cores to estimate the amount of carbon stored in both vegetation and soil. She will use this information to produce detailed carbon stock distribution maps for northern Namibia, parts of Angola, Zambia, and Botswana. These carbon stocks form the basis of potential carbon markets, whereby communities or local authorities are compensated for maintaining or restoring natural vegetation to capture carbon dioxide. Without this initial dataset, we cannot determine the amount of carbon our woodlands store, which is essential information for carbon markets and trading.

The detailed ground-level data from our plots complement data collected using satellites and other large-scale research. NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) is an instrument installed on the International Space Station that produces 3D images of the Earth’s surface using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology. Another method, called Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), produces even more detailed 3D models using earth-based lasers.

Hermane Diesse, a PhD student at NUST, combines information from GEDI and TLS with data from plots at three of our study sites and other sites in the SEOSAW network, extending beyond Namibia. He is investigating how rainfall and fire interact with forest structure, and how the canopy and subcanopy layers influence species diversity and plant biomass above the ground (i.e., excluding roots). His work shows that small trees and shrubs in dry woodlands contribute a greater proportion of the total above-ground biomass than those in wetter woodlands, which are dominated by larger trees. While wetter areas generally support higher overall levels of above-ground plant biomass, drier areas support a unique share of both biomass and diversity in their understorey components.

These results have significant implications for conservation strategies and carbon credit allocation. Many carbon assessments exclude trees and shrubs smaller than 5 cm or 10 cm in diameter, leading to the underestimation of both carbon storage and biodiversity

value. Diesse’s work highlights the importance of incorporating small trees and shrubs into carbon assessment protocols, particularly in dry woodlands. This would more accurately capture the carbon storage potential of these ecosystems and significantly increase their estimated contribution to climate mitigation.

Gabriel IK Uusiku, a Master’s student at NUST, is investigating the relationship between seasonal leaf changes (known as phenology) and litter decomposition in semi-arid savannas. Using the plots at Ongava Game Reserve equipped with phenocameras (camera traps with the movement sensor disabled), he captures daily vegetation imagery to track seasonal canopy dynamics.

The dominant trees in this area include Mopane (Colophospermum mopane), Purple-pod Cluster-Leaf (Terminalia prunioides), and Blue-leaved Corkwood (Commiphora glaucescens), all of which lose

their leaves in winter. The leaves then accumulate on the ground as leaf litter, thus returning nutrients to the soil. The link between leaf greenness (as determined by the cameras) and the amount of leaf litter that accumulates and decomposes on the ground provides insight into the functioning and resilience of savanna ecosystems.

The NUST team, led by Prof. Vera De Cauwer, has significantly enhanced the impact of their individual research projects by contributing to the SEOSAW network. Students from as far afield as the University of Edinburgh, or as close as our neighbouring countries, can tap into this valuable database to answer questions that no researcher could achieve alone. Each of the plots in Namibia is part of a much larger puzzle. While each piece is important, the state of southern Africa’s woodlands is only revealed when we put the pieces together and view the whole picture from multiple research perspectives.

By: Gail Thomson and Mike Murray-Hudson

by John Mendelsohn

The Okavango Delta and its upstream catchment, which supports hundreds of thousands of people, are under threat. While the potential for oil extraction in the catchment garners international attention, this life-giving ecosystem seems on track to quietly die by a thousand other cuts. A new report by John Mendelsohn for The Nature Conservancy reveals that threats to this system continue growing each year.

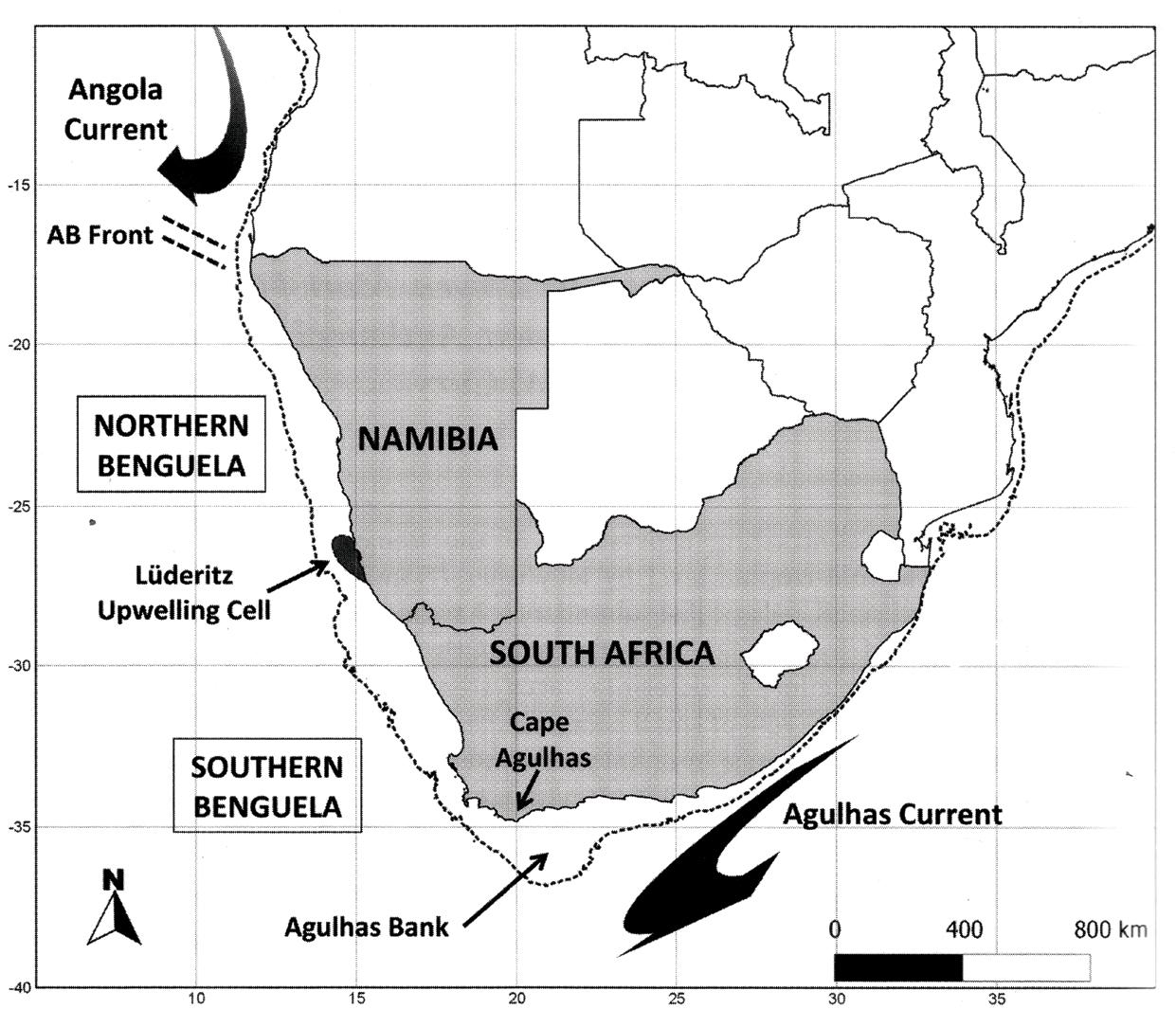

Water from Angola flows along Namibia’s northern border before crossing over into Botswana, where it eventually fans out in the Delta and slowly seeps into the Kalahari sand. Two main rivers in Angola supply the Delta – the Cuito in the east and the Cubango (also known as the Kavango in Namibia) in the west.

The western Cubango River is largely responsible for the seasonal flood pulses in the rivers and Delta’s floodplains that are essential

for plant growth, fish spawning, bird nesting, and watering the huge number of elephants and other mammals that attract tourists from all over the world. Indeed, a substantial part of Botswana’s lucrative tourism industry relies on the Cubango River and the abundance of life it supports in the Delta. Throughout its entire course, the Cubango also supports people, crops, and livestock that utilise its water and the surrounding land. Yet, if development continues in its current uncontrolled manner, the river and its ecosystem may become so degraded that the health and well-being of people and wildlife are negatively affected.

The heart of the problem lies in the inadequate management of the entire river system and its surrounding environment. Although Angola, Botswana, and Namibia established the Permanent Okavango River Basin Water Commission (OKACOM) in 1994 as a means of promoting cross-border cooperation and managing the Okavango River system, 31 years later, a formal water-sharing agreement remains absent.

Controls over the use of land and water in Angola and Namibia are also virtually absent, making both land and water essentially free for the taking and use.

Consequently, commercial and subsistence developments along the river continue as though this water will never run out or become too polluted for use. Mendelsohn’s 2024 report reveals that threats to this system are growing each year, with no indication that they are slowing or being controlled.

Commercial agriculture in Angola and Namibia along the Cubango/ Kavango is expanding, but there are no controls over how much water each farm consumes, or how much fertiliser and pesticide is used. Pollution is not monitored anywhere. Between 2020 and 2024, the land used for large irrigation schemes in both countries increased from 6,200 hectares to just over 8,000 hectares. Management of several state-owned farms (known as ‘green schemes’) was transferred to the profit-oriented private sector in Namibia over the same period.

While privately run commercial farms are likely to bring jobs and increase food production per hectare, these operations must be regulated. Land and water are not infinite resources. The use of fertilisers and pesticides should be controlled and limited to minimise the levels of river pollution.

Growing numbers of local residents are also commercialising their farming operations by selling their produce in towns, which allows them to invest in mechanised ploughing and fertilisers and to expand their fields. In south-eastern Angola, the rate of land clearing increased from 41.5 hectares per day in the five-year period immediately following the end of the Angolan civil war to 129 hectares per day in 2016-2020. In the most recent period (2021-23), land is being cleared for agriculture at a rate of 114 hectares per day. This development is a double-edged sword: it reduces rural poverty, but damages the land and the river.

Charcoal production, plantations, and mines

Like agriculture, charcoal is produced on large and small scales. The small-scale producers sell their charcoal along roads to people living in the main towns in Angola. This may be the only source of cash income for many rural households.

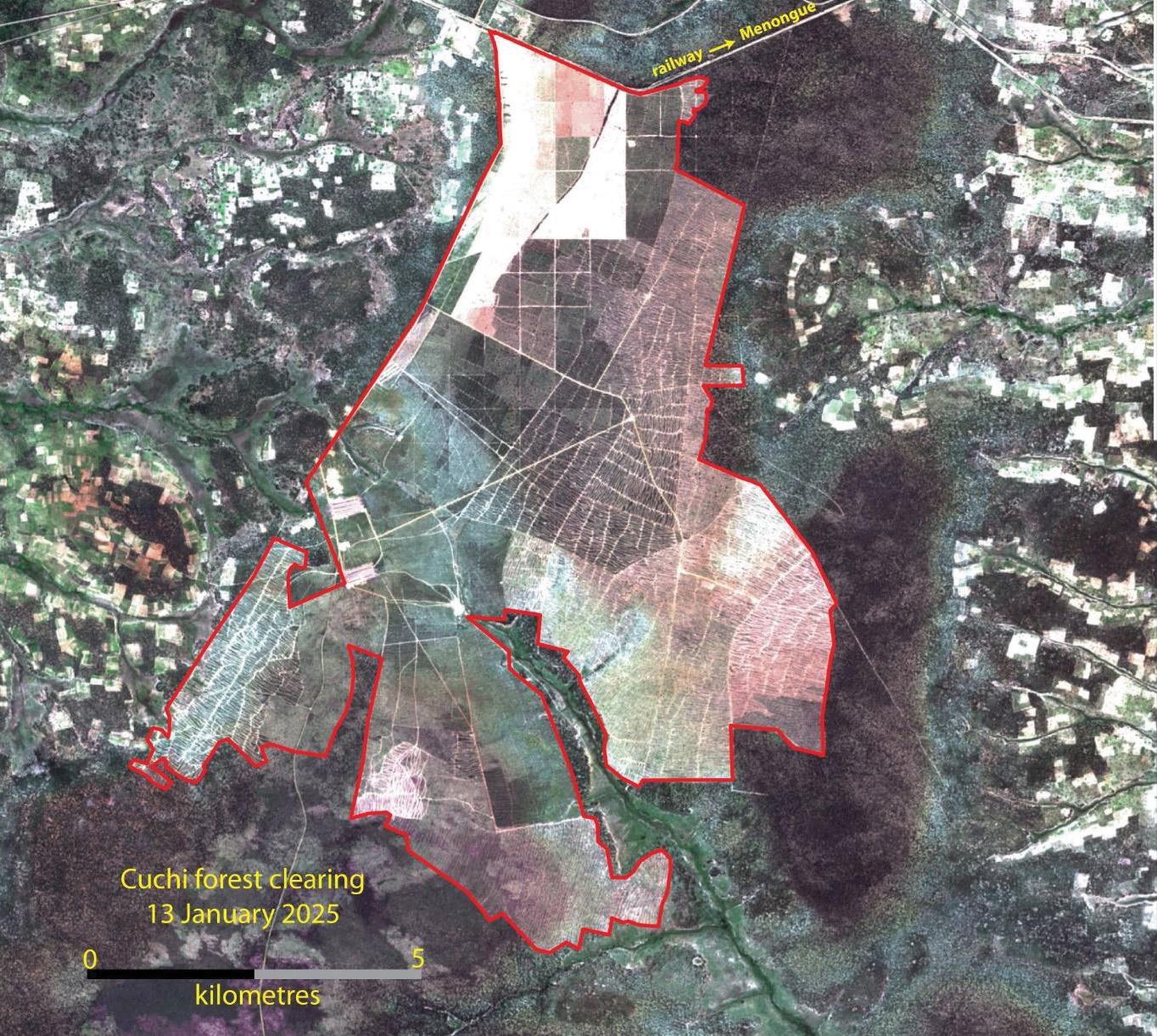

Large-scale land clearing for charcoal production is of much greater concern. In 2022, 30 farms covering 153,000 hectares were designated for clearing by a local authority in Angola. Some of these farms are already being cleared of woodland (approximately 8,400 hectares by

September 2025) to produce charcoal, which is then used to smelt iron ore from a local mine. This open-cast iron mine is located within the river basin.

Ironically, the pig iron produced here is marketed and exported as ‘green’ or ‘carbon-neutral’ because the cleared land will be replanted with non-native eucalyptus plantations (gum trees). These plantations host very little biodiversity, are thirsty, and most other plantations like them in Angola have not grown well. Local people in this area value the natural miombo woodlands and resist the government’s plans to expand these operations.

The much-publicised oil exploration in Namibia and Botswana by Recon Africa is yet another potential threat to the system. At this stage, it seems like the potential for oil in this area was over-hyped for commercial reasons, and the project is unlikely to come to fruition. Even if the exploration comes to nothing, this is a cautionary tale of how external investors can override concerns about local livelihoods and the environment. Recon Africa has recently expanded its explorations into the lower Cubango catchment in Angola.

This small vegetable farm near Rundu is a well-managed co-operative that produces food and supports many livelihoods. This is all on 34 hectares and with relatively little use of Okavango water - an example of positive development in the area.

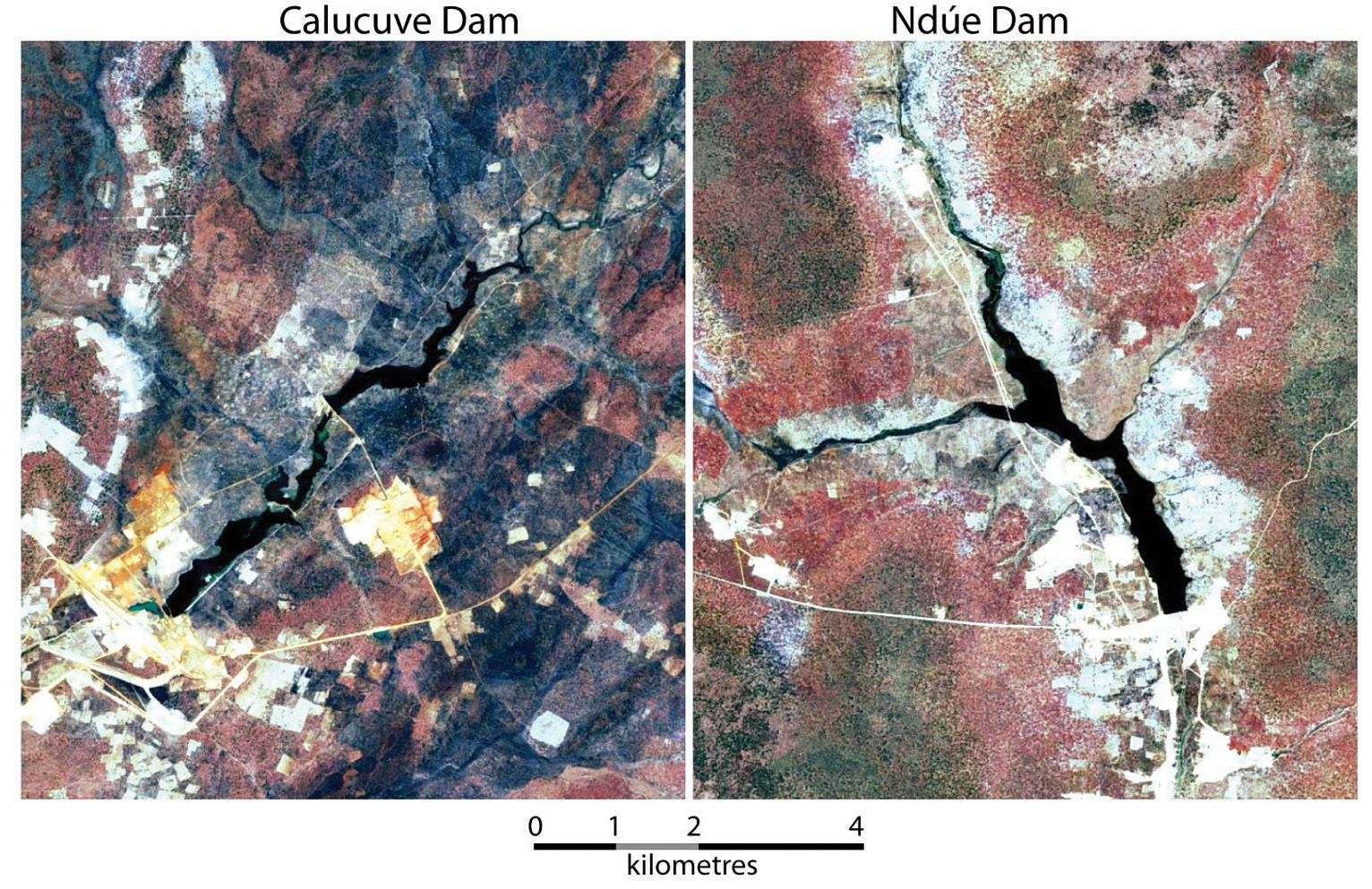

New dams Angola is currently building two large dams (the Calucuve and Ndué) along drainage lines of seasonal (ephemeral) rivers. Since the rainfall in this area is unpredictable and the catchment area is sandy (most water will seep away before reaching the dams), it is likely that these reservoirs will often run dry. The current plan for these dry periods is to redirect water from the Cubango River into these dams, thus taking large amounts of water from the river system.

In Namibia, plans to channel water from the Kavango River to existing dams around Windhoek are frequently proposed, especially during droughts. The current idea is to take water from the river at Rundu during peak river flow periods. Flood pulses at these peak periods are critical for the Okavango Delta ecosystem and for floodplains along the major rivers.

These plans do not account for the increased volumes of water being extracted from the major rivers in Angola and Namibia in recent years. Between 2017 and 2023, along the section of the river that forms the border between Namibia and Angola, the number of small water pipes increased from 25 to 130, the number of medium-sized pipes increased from 44 to 95, and the number of large pipes from 20 to 25 or 26. Most of these pipes are on the Namibian side of the river.

A roadside market on the main road between Chinguar and Cuito, where locally grown vegetables are the main produce for sale. Many changes in land uses and settlement patterns in the catchment reflect the increasing needs of residents for cash incomes

One of two banks of charcoal furnaces used to convert miombo trees into charcoal. Each bank has 400 furnaces which are clearly visible in Google Earth at these coordinates: 14.735 South and 17.04 East

For many years, it was assumed that measurements of flow at Rundu reflected the volumes of water leaving Angola at the Katwitwi border post. New data reveal that this is not the case, and that large volumes of water are indeed lost from the Kavango River before it is joined by the Cuito River from Angola. If even more water is taken from the Cubango/Kavango by either Angola or Namibia, the effects on the Delta in Botswana could be severe.

Migration from rural to urban areas is inevitable as both Angola and Namibia develop, resulting in larger towns that have substantial requirements for land and water. Many villages in Angola are rapidly becoming towns, while several towns are growing into cities in the catchment area of the Cubango River. This trend can have positive effects, as people living in towns have greater access to services and income opportunities than those in rural areas. The rural environment should also benefit if fewer people rely on slash-andburn subsistence agriculture.

Urban development nonetheless poses challenges for the environment. Solid waste and sewage from towns are significant sources of river pollution, and there is already evidence that the Namibian section of the river is being contaminated by chemicals and waste generated by agriculture and urban areas.

The environmental impacts of growing urban areas can be mitigated through proper town planning, waste management, and efficient water use. Like many of the other challenges outlined here, these require strong political will, wide public awareness, and collective action to overcome.

The key to saving the Okavango: public interest and political will The future of the whole Cubango/Kavango river system, including the Okavango Delta, lies with the three countries that manage and benefit from these waters. The Okavango Delta supports a thriving tourism industry that contributes substantially to Botswana’s economy, but the concerns raised above are not limited to Botswana. If development

Sentinel satellite images taken on 25 Sept 2025 of Calucuve (15.57 South and 16.04 East) and Ndúe (15.81 South and 16.55 East) dams nearing completion.

continues in the unregulated “free-for-all” way that is currently happening in Angola and Namibia, people and the environment in all three countries will suffer.

With land and water so easily available, many more large, irrigated farms can be expected along the Cubango/Kavango and Cuito rivers. Consequently, downstream flows will be reduced and increasingly polluted by agricultural chemicals.

These changes and challenges are inevitable unless substantial controls and measures are implemented to minimise environmental impacts. Both existing and new commercial crop farms must use water efficiently and minimise artificial fertiliser inputs. Underground water should be used more to supply farms, towns, and other users.

Urban growth will present additional challenges, but towns that are properly managed can accommodate a large number of people and enhance their living standards without compromising the environment.

Major new developments such as dams, mines, and oil production should be approached with the appropriate levels of caution and public participation. Are the damages that such projects cause worth the economic gains that they may produce? Clearing vast swathes of biodiversity-rich miombo woodland to replace it with eucalyptus plantations is one example of ill-conceived development. The people living in the affected area will lose their natural resources and access to ancestral lands, while a private company profits from exporting green-washed pig iron.

Choosing positive development trajectories over short-term gains requires strong political will, which is driven by public concerns and

understanding. The people living in Angola, Namibia, and Botswana need to be aware of the threats posed by water loss, pollution, and land degradation in their immediate vicinity and upstream.

Plans to redirect water from the river to dams in Angola and Namibia should not be implemented without consulting Botswana. The OKACOM platform, which is intended to promote co-management of the Okavango system among the three countries, needs to be active and taken seriously by all stakeholders, especially the governments of the Basin States.

The Okavango ecosystem may be known globally for its final destination – the Delta – yet this is certainly not the only reason to manage it wisely. Thousands of people live along the river and within its broader catchment area, thus depending directly on this ecosystem for their survival and well-being. Their rights to a clean, functional environment and sustainable economic development must be considered together, rather than as separate issues. It is time for the governments of these three nations to heed the ecological warning signs and chart a more sustainable path forward for their people and the Okavango River Basin.

Full report: Mendelsohn, J. (2025). Threats and developments in the Catchment of the Cubango/Okavango River in Angola and Namibia: Update and Perspectives in 2024. Compiled for The Nature Conservancy.

By: Giraffe Conservation Foundation

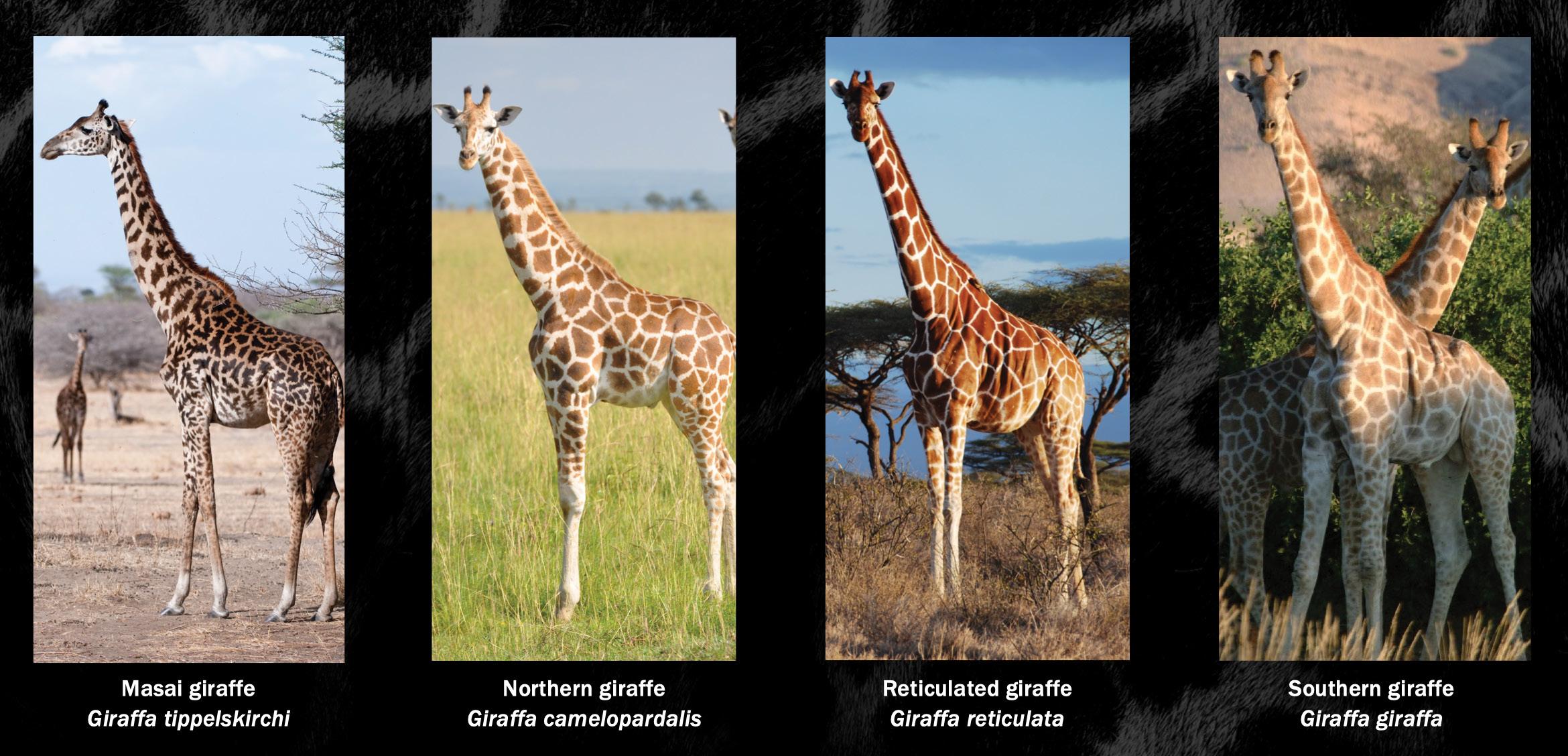

The year 2025 will be remembered as a turning point in the story of the giraffe. Long familiar as one of Africa’s most iconic animals, giraffes are undergoing a transformation in the way science, conservationists, and the public understand them. For more than 250 years, all giraffes were thought to belong to a single species, Giraffa camelopardalis. That picture has now changed dramatically. In August, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) formally recognised four

distinct giraffe species: the Masai giraffe, Northern giraffe, Reticulated giraffe, and Southern giraffe.

How do we know that there are four species of giraffe?

The detailed taxonomic review was conducted by the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Giraffe & Okapi Specialist Group Taxonomic Task Force. This review evaluated extensive genetic data from multiple peer-reviewed studies. Many of these studies focused on giraffe genetics, making the giraffe one of the most genetically well-studied large mammals in Africa.

Complementing the genetic work, the review also incorporated studies of the physical form and structure of the giraffe, including notable differences in skull structure and bone shape across regions. Spatial use and biogeographic assessments also considered the role of natural barriers – such as major rivers, rift valleys, and arid zones – that could have contributed to evolutionary isolation. Together, these multiple lines of evidence provide clear scientific support for elevating certain giraffe populations to full species status, reflecting their distinct evolutionary histories.

This research was largely spearheaded by the Namibian-based Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF), in partnership with many African governments, conservation organisations, and academic institutions. Most notably, the genetics research was undertaken by GCF in collaboration with the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre (SBiK-F). These findings, first revealed in 2016, revealed differences between giraffe lineages as deep as those separating polar bears and brown bears, an extraordinary discovery for such a visible and widely distributed animal. As Professor Axel Janke of SBiK-F remarked, “to describe four new large mammal species after more than 250 years of taxonomy is extraordinary.”

Conservation applications of the new classification

This reclassification is not simply an academic curiosity. As Dr Julian Fennessy of GCF emphasised, “each giraffe species faces different

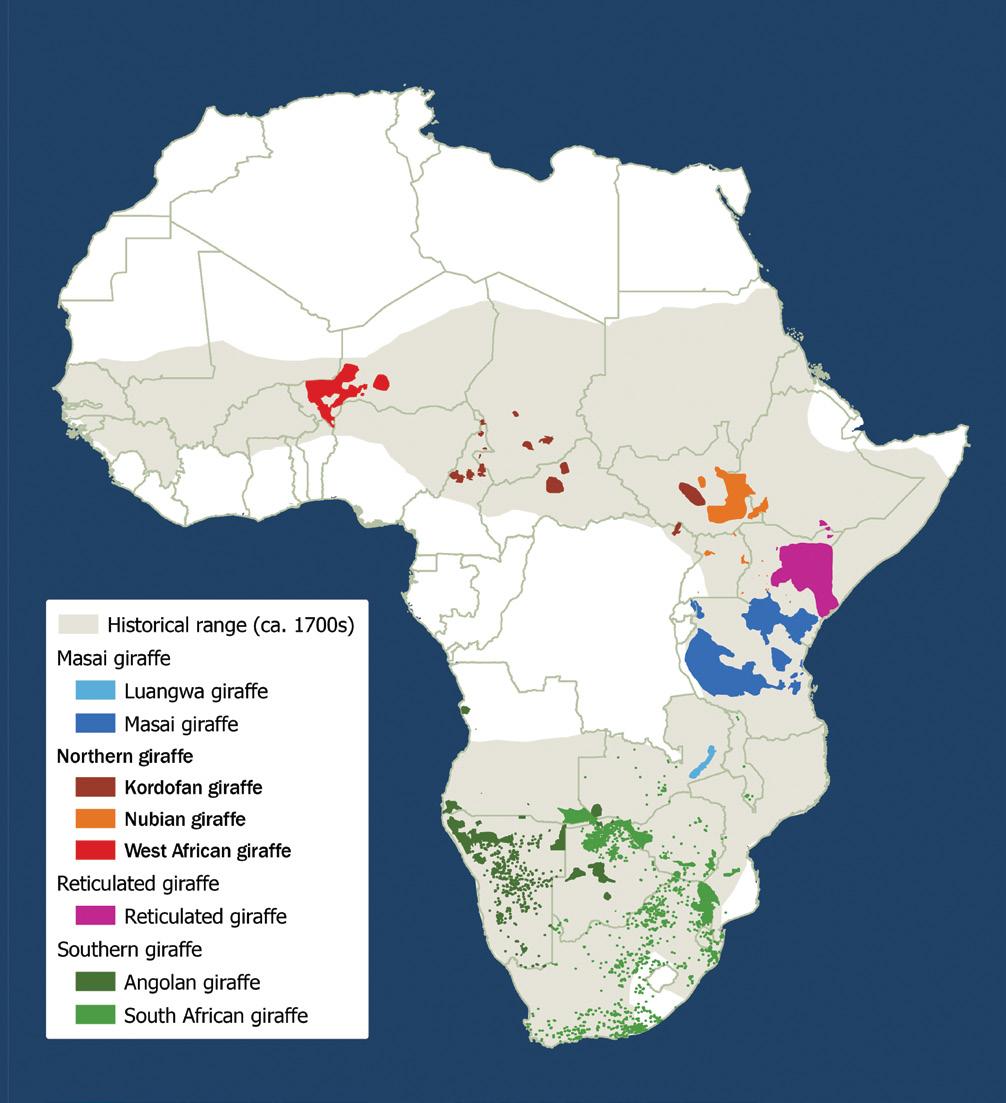

threats, and now we can tailor conservation strategies to meet their specific needs.” For the first time, conservation priorities, funding streams, and international policy will be able to focus on speciesspecific requirements, recognising that the ecological challenges facing Northern giraffes in Niger are not identical to those for Southern giraffes in Namibia or Masai and Reticulated giraffe in Kenya.

The IUCN decision coincided with the release of GCF’s State of Giraffe 2025 report, which synthesised data from across the continent to provide the most accurate overview yet of giraffe numbers and distribution. Together, these two milestones represent a historic shift in our understanding of giraffe taxonomy, numbers, distribution, and conservation status.

The GCF State of Giraffe 2025 report is based on data compiled in their newly established Giraffe Africa Database (GAD), a platform designed to collate survey results and provide a consistent picture

of each population’s status. Because survey methods vary widely in reliability, the report applies an Information Quality Index, assigning higher confidence to ground-based counts and individual monitoring, and adjusting aerial estimates upward to account for under-detection. This methodological rigour matters because past assessments often underestimated populations, or were based on rough guesses rather than systematic data. By combining hundreds of data sources, including government surveys, non-government reports, and peerreviewed studies, GCF has created the clearest view yet of how all giraffe species and their populations are faring.

The overall picture is one of cautious optimism, with significant caveats. Across Africa, the combined numbers of all four giraffe species now total approximately 140,000 individuals. This is higher than estimates suggested over the last two decades, largely due to improved survey coverage, data sharing, and increased conservation

efforts, but it still remains well below historical levels. In 1995, populations were far larger, and in several cases, they have fallen by more than half in just thirty years. When we consider the four distinct species separately, however, we discover a more complex and dynamic story.

The Masai giraffe, spread across Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Zambia, now numbers around 43,900 individuals. While their numbers have remained stable over the past five years, this species declined by nearly 40% during the previous three decades. The well-monitored Kenyan populations in the Amboseli, Tsavo, and Masai Mara ecosystems appear steady, and Rwanda’s Akagera National Park has seen impressive growth from a small reintroduced herd. Tanzania, historically a stronghold, has remained poorly surveyed in recent years, creating a troubling data gap. The Luangwa subspecies of Masai giraffe comprises a small, isolated population of approximately 764 individuals in Zambia. Although this subspecies has increased by 18% over the past five years, it still remains far below historical estimates.

The status report for Northern giraffes paints a more sobering picture. Numbering 7,037 across Central, East, and West Africa, a 19% growth rate during the past five years masks a catastrophic 70% decline since the mid-1990s. The three subspecies tell the story in sharper detail. The Kordofan giraffe is now primarily concentrated in Chad, where it holds two-thirds of the population in Zakouma National Park. In contrast, Cameroon and the Central African Republic have experienced significant declines, with perhaps only a handful of individuals remaining in the latter. The Nubian giraffe subspecies has fared somewhat better, with nearly 4,000 individuals, many of which reside in Uganda’s Murchison Falls National Park and Kenya’s Ruma National Park; however, the population in South Sudan is in sharp decline. The West African giraffe, once numbering just 70 individuals in Niger, has recovered to a minimum of 669, but remains highly vulnerable due to its small range and the fragile political situation of the country.

The Reticulated giraffe, instantly recognisable by its lattice-like coat pattern, now numbers about 20,900. Kenya holds almost the entire

global population, with key strongholds in Garissa, Laikipia, Marsabit, Meru, Samburu and Wajir. Together, these areas account for 98% of their total. These populations are increasing, but Ethiopia and Somalia remain poorly surveyed, with perhaps only a few dozen surviving in these insecure regions. Overall, the population of Reticulated giraffes has increased by 31% since 2020, but remains 42% lower than the 1995 levels. Conducting more surveys in their remote areas would help gain a better understanding.

The Southern giraffe, by contrast, is a modern-day conservation success story. At nearly 69,000 individuals, it is the most numerous species and has more than doubled in size over the past three decades. Namibia alone holds nearly 14,000 of the Angolan subspecies, while South Africa hosts almost 30,000 of the South African subspecies. Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe also maintain strong populations, and reintroductions into Malawi and Mozambique have been successful. The Southern giraffe demonstrates what is possible when robust national conservation frameworks, community engagement, and private landholders align to protect and expand populations.

Using our knowledge to guide giraffe conservation

While these species-level assessments provide clarity, it is essential to note that each species and its local populations often face very different circumstances. Some small, isolated populations are declining rapidly and could vanish within years without intervention. Others, especially where conservation translocations and management strategies are in place, are recovering. Countries that have developed National Giraffe Conservation Strategies and Action Plans – such as Chad, Kenya, Niger, and Uganda – have seen positive outcomes. Despite progress, challenges remain significant. Habitat loss and fragmentation resulting from the expansion of agriculture and infrastructure are reducing the giraffe’s range across East Africa. Poaching continues in regions with weak governance, with giraffes hunted illegally for meat or traditional uses. Climate change is altering vegetation and water availability, adding further pressure to these ecosystems. In many areas, particularly in the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Tanzania, data gaps hinder effective planning. Without sustained monitoring, conservationists cannot accurately track trends or respond to emerging threats.

This is why the IUCN’s decision to recognise four giraffe species carries such weight. By treating them separately, the global community can direct conservation funding and policy toward the species most at risk. Preliminary findings suggest that three of the four species – the Masai, Northern, and Reticulated – are threatened, underscoring the urgency of targeted action. The Southern giraffe, though currently secure, still requires careful management to prevent future declines. Stephanie Fennessy, Executive Director of GCF, captured the stakes clearly: “What a tragedy it would be to lose a species we’ve only just discovered.”

As the leader in giraffe conservation throughout Africa, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation provided not only updated numbers with their State of Giraffe 2025 but also a model for how to build conservation around robust science. By integrating genetic discoveries, field surveys, and international collaboration, it sets the stage for a new era of giraffe conservation. 2025 will be remembered as the year when giraffes were finally seen not as one animal but as four –each with its own history, challenges, and prospects. It may also be remembered as the year when the world decided to stand tall for these gentle giants and initiated targeted efforts to ensure they will continue to roam Africa’s landscapes for generations to come.

By: GIZ and KfW

Photos by GIZ

In Namibia, nature conservation and sustainable use are enshrined in the constitution, making it a global leader in this regard. Namibia’s approach to protecting natural heritage focuses on empowering communities as stewards of the land, rather than relying solely on regulation and law enforcement.

Over 40 percent of Namibia’s land is designated for conservation and sustainable use, exceeding the international goal to conserve 30% of the earth’s surface by 2030. Central to this achievement is Namibia’s community-based conservation model, which grants rural communities rights to use their natural resources sustainably. Through communal conservancies and community forests, local people manage wildlife and benefit from its protection. This approach has transformed conservation into a grassroots movement, with 86 communal conservancies and 47 community forests covering around 20 percent of Namibia’s territory and benefiting over 244,000 people.

This model has gained international recognition, thanks to the Namibian Government’s vision for sustainable and inclusive use of natural resources for the benefit of all Namibians. A key partner in

this journey has been the Federal Republic of Germany, which has provided consistent financial, technical and policy support since 1990 through institutions like KfW Development Bank and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

With over € 1.6 billion (approx. N$ 32 billion) in development assistance to Namibia over the last 35 years, Germany has made a significant contribution towards Namibia’s achievements in conservation and sustainable development. We share a few highlights from this long and productive partnership here.

KfW – supporting national parks and community conservation Through the Namibia National Parks Programme (known as NamParks), KfW helped build and upgrade critical infrastructure in national parks for the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) – including 13 new park management stations, administrative buildings, staff accommodation and tourism facilities. These investments have improved the efficiency and professionalism of park management, made parks more accessible and attractive to tourists, enhanced biodiversity monitoring, and contributed to job creation in

neighbouring communities. This support programme has strengthened the livelihoods of an estimated 180,000 Namibians and improved wildlife management in these critical protected areas.

Looking ahead, sustainability is a pressing concern. While donor support has been vital, reliance on project-based funding leaves Namibian national conservation efforts vulnerable to economic shocks and geopolitical developments. Recognising this, KfW committed € 3 million toward establishing a sustainable financing mechanism for Namibia’s state-protected areas.

Beyond state-protected areas, Germany has supported Namibia’s Community-Based Natural Resource Management Programme (CBNRM). The Community Conservation Fund of Namibia (CCFN) was established with support from KfW to provide long-term support to community conservation areas. Through the CCFN, conservancies receive grants to support operational costs, invest in tourism infrastructure, and maintain wildlife monitoring and anti-poaching patrols. This financial stability was vital during the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a sharp drop in tourism revenues for many communities. Around 9,400 local beneficiaries and their families received support during this time of need through the Conservation Relief, Recovery and Resilience Facility (CRRRF) managed by the CCFN.

Germany has also played a significant role in mitigating humanwildlife conflict. In regions like Kunene and Zambezi, communities face numerous threats from wildlife – including elephants eating crops and destroying water infrastructure, or predators such as lions attacking livestock. These events can provoke retaliation against wildlife and erode community support for conservation. KfW has therefore funded numerous mitigation measures, including predator-proof livestock

kraals, early warning systems and water access points for wildlife away from villages, providing communities with both security and incentives to continue coexisting with wildlife. In the Ombonde landscape alone, the conflicts with lions declined by 80%.

Poaching remains a threat within and beyond state-protected areas, especially to high-value species like rhinos and pangolins, which stretches conservation resources. KfW has bolstered anti-poaching efforts by providing equipment, trainings, and infrastructure to support the MEFT’s Wildlife Protection Services (WPS).

GIZ – providing technical support for policies, resilience and livelihoods

The support Germany provides through financial cooperation is complemented by Namibian-German Technical Cooperation partnerships. Technical Cooperation – implemented mainly through GIZ – is designed to strengthen natural resource management, policy development and implementation while promoting good governance and capacity development.