11 minute read

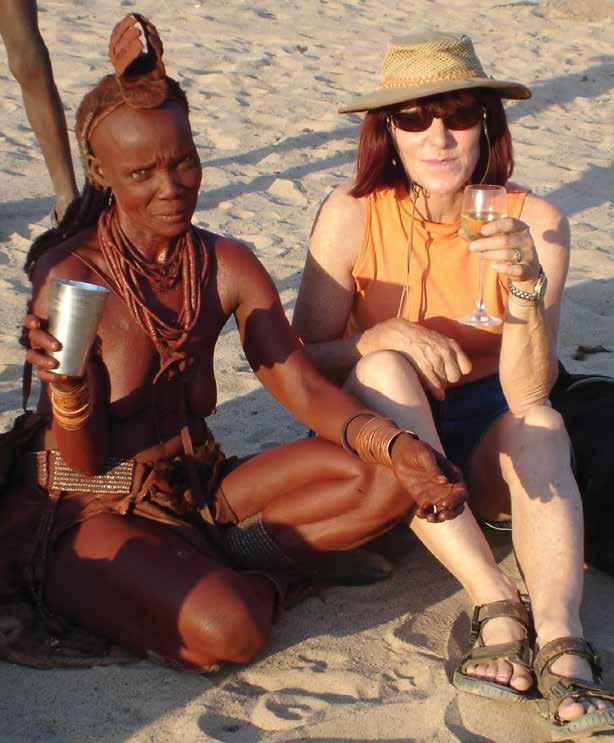

ETHOS OF ANCIENT with Dr. Margaret Jacobsohn

ETHOS OF ANCIENT

Dr Margaret Jacobsohn is a Namibian writer, anthropologist and community-based conservation specialist. She the cofounder and chairman of the board of the IRDNC, Integrated

Rural Development and Nature Conservation – an NGO, trust and pioneer of

Namibia’s community-led conservation programme, which started as a small pilot project in the 1980s and went on to become an incredible Namibian success story.

An authority on the social organisation and cultural economy of the seminomadic Himba people of Namibia and Angola, her PhD thesis was based on more than five years of living and working with remote Himba communities. She is the author of Himba: Nomads of Namibia, and her memoir, Life is Like a Kudu Horn, was published by Jacana in 2019.

For her work, Margaret has been awarded some of the world’s top conservation prizes, including the US Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa, which she won jointly with Garth Owen-Smith, the United Nations Global 500 Roll of Honour award and the WWF Netherlands’ Knights of the Order of the Golden Ark.

For the past five years, Margaret has helped to mentor and run a small upmarket mobile safari company, Conservancy Safaris Namibia, which is owned by five Himba and Herero communities through their conservancies in Namibia’s far North West. This is her story.

WHERE IT STARTED

I came here as an archaeologist. I was a journalist for the first twenty years of my life and then became a mature student and went to university quite late in life. I was already nearly thirty and worked at the interface between huntergathering and herding, first in the Cape, through Cape Town University and then on holiday trips to Namibia. I became really interested in working with some modern-day herders and looking at the way in which they used space and technology and material culture.

The Himba were particularly interesting because they were living at a moment of real change. Independence was coming to Namibia, so it was centralised, political control, the cash economy, wage labour – all these things were changing and impacting on this society. I wanted to live with them and try to understand how they were negotiating this change. That’s where it started.

ON HIGHLIGHTS OF HER JOURNEY

My memoir, Life is Like a Kudu Horn, looks at the last three strands of my life. First is the research itself. Second is what I learnt from it – because very often a researcher learns more about him or herself than the people they are actually supposed to be studying. It was such a privilege living with remote rural people for a couple of years; that’s a book in itself. And third is that I started working in community-based conservation and spent thirty years in that, the last twenty-five

WITH DR MARGARET JACOBSOHN

of them running an NGO, but I stepped down as a director seven years ago.

There’s a modern young team of directors, John Kasaona and Willie Boonzaaier, now running IRDNC. I’m on the board – I’m chairman of the board – but apart from working as a consultant in community-based conservation in the region, I’ve lurched very reluctantly into community tourism. I never

wanted to work in tourism. I’m not tactful enough – I used to be called “the blunt instrument” in IRDNC because I call a spade a spade.

For the last four or five years I’ve been helping to run a Himba-owned safari company, which has been very hard work from my perspective because the shareholders are

4 000 Himba people. But the company is actually run by a small technical team who are very experienced and good at what they do, so that’s a part of my life now. It was very

gratifying that the little company called Conservancy Safaris Namibia was able to give N$150 000 in cash back to shareholders at the height of the drought. And 301 families all got a cash dividend in 2016, when they were really battling because two-thirds of the cattle had starved to death in the drought. The company puts about N$500- 600 000 a year back into the communities that own the company and also a little lodge.

ON MODERN TRADITION

You know many Namibians think that traditional is the opposite of modern. There are many people in the world who see them as opposites, that you can’t be traditional and modern – and that’s not true at all. You can be extremely traditional and very modern at the same time, and there are many examples of that in the world. Swedish friends celebrate summer by eating raw fish and doing all kinds of weird Swedish things, but they’ve all got the most modern phones – and the two aren’t in opposition.

The Himba holy fire might be seen as a rather strange custom – the senior elder asks the ancestors to bless the milk from the cattle every morning, and there’s a little ceremony where the ancestors are asked to free the milk of any bad things. Decisions are made around that holy fire. Now this might seem like a quaint, traditional, old-fashioned custom, but it’s not at all. It’s a forum for brilliant environmental and social planning. That holy fire is one of the reasons why the Himba were such superb herders. The Himbas know what they’re talking about. They would say they actually farm grass as much as cattle, and it was often said to me, “Don’t start your farming with cattle, start it with people.” This is why the Himba were among the most successful subsistence cattle herders in the world.

ON COUNTING IN PATTERNS

I also discovered different ways of counting – not just the one, two, three that children learn in school today. I was sitting with a Himba man once, and about eighty goats were streaming past us and he literally said, “Just hang on – there’s a goat missing. I must go and find out what’s happened.”

Out of eighty animals, he knew there was a brown-and-white pregnant goat missing. I asked, “How did you pick that up? Did you count one, two, three?”

He really thought about it. And we went out into the twilight and found this goat giving birth under a tree. If he hadn’t gone, she and the youngster would definitely have been taken by jackals or hyena or something in the night, so she was brought back safely.

What he said was that he forms a pattern in his head, a picture in his mind of black-and-white goats, brown-and-white, all brown, different colours and it’s a dynamic, moving pattern. It’s not fixed because the goats are moving in different ways. But approved by the Ministry of Forestry, but we’ve managed to

he sees when the picture is not right. There are many ways of doing things that we’ve lost before we even understand them.

ON INDIGENOUS BURNING

Since Independence we’ve been working with the San people in what used to be West Caprivi, now Bwabwata National Park. Something very interesting is the indigenous burning there. Indigenous people like the San have been burning for thousands of years and the very healthy savannah landscape we have inherited in Namibia is because of that burning – it’s culturally sculpted, you could say.

FOR MORE, VISIT CONSERVANCY SAFARIS

It’s done for field management – they did burns early in the seasons, as soon as the grass was dry enough to burn, which is a cool mosaic burn that doesn’t destroy trees. If you leave the got a huge fuel load, and if lightning strikes or there’s a manmade fire, then you have this dangerous hot fire that kills trees and burns the whole area.

People are doing indigenous burning again. It’s taken a number of years to re-empower people to get a fire strategy do this over a period of three or four years, so fires are not banned as they were for many years in colonial days and during the first part of Independent Namibia.

We’ve had ten fire ecologists, including Australians, visit us and look at IRDNC’s fire programme with the conservancies in the Zambezi Region. It’s a very good programme.

veld and the grass and it grows for years, you’ve eventually

NAMIBIA’S WEBSITE: WWW.KCS-NAMIBIA.COM.NA

ADVERTORIAL

REBEL WITH A CAUSE

CEO Gys Joubert

You meet Gondwana CEO Gys Joubert in shorts and a linen shirt. He doesn’t do power dressing because he doesn’t give a hoot about status, boxes, titles or hierarchies.

That is not how Gondwana was built. That is not what he signed up for and it isn’t why he was appointed to lead a brand built stubbornly and boldly on innovation and disruption.

Gys is the perfect rebel for the cause. In addition to being the CEO, he is also chairperson of the Gondwana Care Trust, the company’s social investment arm, which serves the communities surrounding their lodges.

The Trust provides for a range of over twenty projects operating across Namibia – including supporting the Sikunga Fish Guards along the Zambezi, who protect the sensitive riverine ecosystem, which includes the southern carmine bee-eater colony. In another project, the excess meat from Gondwana’s Self-Sufficiency Centre in Stampriet is distributed to soup kitchens, orphanages, schools and hostels, and the Trust also provides care and a warm meal to the most needy in the country.

It quickly becomes clear that Gys is not only passionate but also deeply emotional about Gondwana’s unwavering commitment to making a positive impact with every move they make. It is their fundamental purpose.

“We have an unconventional way of doing things. We often do first and then apologise later. And there is just one word that gets used a thousand times when it comes to the decisions we make about the Care Trust, and that is impact. We don’t care who gets the credit or who looks good in the process.

“I have a serious problem with the concept of ‘VIP’. It implies that some people are lesser beings, and that was the basis of apartheid. The very important people in this country are the children who go to sleep without food in their stomachs – not the honorables and the misters and the sirs,” he says. As the emotions well up, Gys takes a moment to compose himself.

“Profit at all costs is easy. And the state of the world as it is now is a result of that. We are in a crisis because it was all for profit at the cost of social and environmental impact. I believe the world is ready for companies like Gondwana. Because the world is fed up.”

Gondwana Collection Namibia is indeed a Namibian postindependence success story, a monument to the potential of a new era of equality, empathy and empowerment.

Gys believes the epitome of this culture translates back to staff accommodation and support for the communities around their lodges.

“You know, we’ve taken over some lodges and seeing the state of that personnel housing … I wouldn’t let my dog live there. To make a lodge look good at the front of house is not that difficult. It’s the back of house that’s not so sexy. Waste management, sewage plants and employee accommodation. You know, we’re currently doing an upgrade at Palmwag, a project of around ten million Namibia dollars. Of that, three million is being spent on staff accommodation and one million on a sewage plant. We had many discussions and different opinions about the guest-experience side of the project, but not one person disputed that four million would be invested to serve our team and the environment,” Gys recalls, noting that improving the benefits for their bottom earners has been a priority on the agenda for the last three years. One of the early board members corrects him, saying that has been so for the last twenty-five years.

“It goes back to the heart and soul of Gondwana. Gondwana is a weird place. The communities and our employees come first. Our shareholders are important stakeholders, but they are not the most important. I’m sorry if it sounds corny, but it’s a company built on love. And love is a bugger because it takes you to the highest peak, but it also knocks you down and kicks you in the ribs. The commitment of the people in this company is ridiculous. Many companies claim that the employees are like family. But the culture at Gondwana seems to be more engaged than that. Family can often be the exact opposite of like-minded or aligned. I like to refer to Gondwana as a movement. Some of my colleagues jokingly refer to us as a cult.

“It’s a cliché to say that our employees are our biggest asset – but how do you live that? The proof is in the benefits and the effort that you constantly put into your bottom earners especially. Double-inflation increases, medical aid, pension – our staff get shares in the business and that to me is extremely important.

“Every decision we make is based on the answer to the same question: What impact will this have? People laugh when we say it, but in Gondwana we have a 1000-year plan …

“Whatever we do, it is not to benefit us or even the next generation. Of course, the work is never done. There are always challenges, but we humans are beings of burden. It’s not negative. It’s our calling. It’s what gives purpose and value to life.”

He contemplates this for a second, then reaffirms:

“The wonderful thing about life here in Namibia is that our ‘burdens’ have an impact. We change lives in this country. We are only 2.4 million people in Namibia. It is possible. We can make it happen. And tourism can play a big role in doing so.”

CONTACT GONDWANA CARE TRUST BY CALLING MS DGINI VISSER ON +264 81 242 5900 OR EMAIL CARETRUST@GCNAM.COM. FIND THE WEBSITE ON WWW.GONDWANA-COLLECTION.COM