3 minute read

Helping Children Heal

Takes More Than Just Medical Knowledge

by Tyler Young

Advertisement

Watching a child suffer through an illness is one of the hardest experiences any of us can go through.

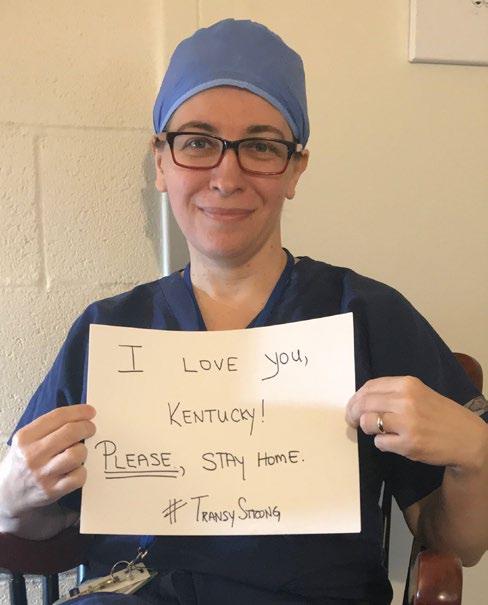

Dr. Ana Ruzic Do ’00, a pediatric surgeon at UK HealthCare Kentucky Children’s Hospital, often meets families on “their worst day,” as she puts it. Not only must she rely on her surgical expertise to step into a situation, her role requires her to be a comforter, someone who can build trust quickly with parents who are entrusting her team with their children who need significant care.

It’s clear when you talk to Do that she truly loves this calling. While she admits the lows can be very low, she speaks on end about the resilience of children and how inspiring it is to see them take on often unfathomable health challenges and heal, whether it’s quickly or years down the road.

“A child just wants to be a child and be done with whatever’s going on here,” she says. “The adults, we walk through this world, sometimes carrying the weight of the world within us, and often do so with little grace — and we tend to struggle through it. But a child, as long as they are given a loving environment, they don’t need much more. They are incredibly resilient and very motivated to go back to being a child.”

It’s a role that she’s been forced to adapt to during the COVID-19 pandemic. Simple nonverbal communications like smiles and hugs are frustrated by masks and physical distance. To compensate, she relies even more heavily on the hospital’s child life specialists, who find creative strategies to comfort and even distract the children during medical procedures and recovery. She believes in a posture

of calm and empathy to help the parents feel secure. And she’s a firm believer that eyes can transmit just as much care as a smile.

And while most doctors typically are able to leave the world of infection behind when they go home, now they’re bombarded with the new reality of a novel disease lurking all around them.

“None of us knew how it would affect our role at work or at home,” she says. “But it also gave us a purpose. We, at the end of the day, still have a place to go, still have a meaning in this job and a sense of purpose. As anxiety-producing as it is to work in health care right now, at the same time it’s rewarding to be part of this process.”

In a children’s hospital, a successful discharge requires many moving parts, all working independently toward the same goal. It includes the food service staff, doctors, housekeeping workers and nurses. There are rarely perfect answers to these illnesses, and it takes more than just medical knowledge to achieve the desired outcome.

In short, there’s a huge difference between being a diagnoser and being a doctor.

She actually likens it to preparing for medical school by studying the liberal arts at Transylvania.

“I didn’t learn medical diagnosis at Transylvania, but I learned how to process information, to have difficult conversations,” she says. “What made

me grow were the small classes, true individual attention and genuine search for real questions. I didn’t learn how to just answer test questions. I learned how to think for myself, how to question data and how to put it all together. That is one of the most difficult things for me to teach my students and junior residents, that the answer is not always a simple yes or no.

“You learn to think in philosophy class, in history, in music. You need basic science knowledge in chemistry and biology, for sure, but those alone don’t teach you to become a doctor. You can’t learn that from a book — you have to learn how to live it.”