8 minute read

Raising a Racially Sensitive Child

By Megan M. Seckman

In early June, protests spanned the globe in a unified call to end systemic racism and police brutality toward people of color. Bands of peaceful protestors filled the sidewalks in Old Louisville, downtown, and the east and west ends of our city, locking arms and showing up despite a pandemic, tear gas, and 90-degree heat.

Sadiqa Reynolds, president and CEO of the Louisville Urban League, caught up with Today’s Woman amidst a media storm, a little breathless and exhausted from the week’s traumatic events, to discuss what parents can do to raise a racially sensitive child. Sadiqa, an activist and mother of two herself, says that the first step begins before your children are even born. Raising racially sensitive children starts with being racially sensitive yourself. Parents need to examine their choices and optics of race — examine their own personal biases and prejudices. Consider who you are hiring to clean your house or do your landscaping and who you choose to be your lawyer, physician, business partner, friend, or neighbor. Our children need to see diversity in all sectors, including our bookshelves, Sadiqa says. We can read books with black and brown heroes to our children when they are still in the womb, and be intentional in seeking out culturally competent resources like Play Cousins Collective.

“We must have a different conversation about race, and stop painting people with broad brushes.” Sadiqa says we need to understand the media’s role in creating these stereotypes and perpetuating systemic racism. “Above all, we need to teach our children to ask questions. It’s a tough time to be a parent...We need to talk about the news, be honest about where the flaws are, and how African Americans are being portrayed. But we don’t have to pretend to know everything, we just have to keep asking questions ourselves, and dig deeper to look at the root causes [of our city’s problems]. We all need to have a diverse feed of information.”

Ultimately, Sadiqa asserts, being a critical thinker will not only make us, but will make our children, better human beings.

ACTIVELY CHOOSING ANTI-RACISM

Catherine McGeeney, director of communications at the Coalition for the Homeless and mother of three, says the first step in raising a racially sensitive white child is to accept the systemic racism present in our city.

“I’m a white mom of three white kids, and we live in a country where my family benefits from centuries of racist institutions — institutions originally designed for the benefit of white people. We didn't build those systems, of course, but we benefit from them, and I believe it’s our moral responsibility to recognize that, then use our privilege to fight those injustices,” says Catherine, who is also a member of Parents for Social Justice, a grassroots organization dedicated to helping parents of young children participate in progressive activism in Louisville.

Systemic racism, she notes, can seem like a complicated concept to explain to white children, but it’s all around us, so it’s easy to point out “once you accept that it’s real,” Catherine says. “White parents often struggle with knowing when it's appropriate to discuss things like stereotypes and race, and my husband and I have wrestled with those questions ourselves. But it’s important to note that even the ability to opt out of such conversations is a privilege of being white; people of color talk to their young children about race to protect them. “One of the starting points for our family has been telling more accurate stories about American “WE MUST HAVE A history.” Catherine notes, “When they learn about the DIFFERENT CONVERSATION Revolutionary War, we need to teach them that slavery was preserved in the creation of our young ABOUT RACE, AND STOP democracy, that most of the founding fathers were slave owners, that our country was built on the PAINTING PEOPLE WITH backs of slaves — and that our laws and policies have continued for centuries to be unjust. We BROAD BRUSHES.” need to show them pictures of the presidents and ask why they think we have only had one black — SADIQA REYNOLDS man (and no women at all, much less a woman of color).”

When we acknowledge systemic racism as a reality that runs through our history, Catherine believes it lays the groundwork for understanding where we are now in our struggle with racial injustice. But Catherine believes education is not enough. “As Ibram X. Kendi has said, it is not enough to not be racist; we must be anti-racist. White parents hold the responsibility not only of being anti-racist ourselves, but also of raising anti-racist children. And much like love itself, choosing anti-racism is not a one-time thing. It is something we must actively choose over and over again, a lens through which we must see all the decisions we make in the world. It's a journey, not a destination.”

The good news, Catherine believes, is that young children are naturally empathetic, loving, sensitive, and sweet. “They feel sadness when things aren't fair or just, so in my experience — with the right framework — it’s not much of a stretch for them to recognize injustice in the world and to be moved toward action. In the moments when they see that injustice clearly, you can take an easy action — have them hold up a sign at a family-friendly protest, or host a lemonade stand and donate the proceeds to a bail fund or other important cause. And just by modeling anti-racist actions on your own, your children will absorb a lot.”

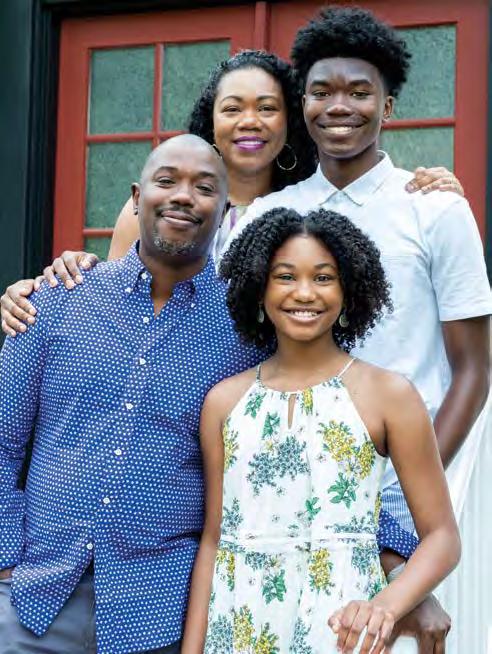

YOU HAVE TO BE TWICE AS GOOD

Empowerment is the tenet touted throughout the home of Dr. Tanya Franklin and Stephen Franklin. The Franklins say they teach their children that prejudice is on the perpetrator. The baggage that people carry doesn’t impact how you should carry yourself. We teach our children — who come from a mother who is a doctor, a father that is a professional, and grew up with the Obamas — that the ignorance of prejudice shouldn’t define how you see yourself. It is a problem that other people have, so shame on them.”

But as a black family in a primarily white east-end neighborhood, discussing race is not an option. “Diversity is forced on us whether we want it or not. White people have the choice in this city to live in a bubble. Most black people, however, have experienced prejudice,” Stephen said. “I hate to say it, but it is just the fact. Prejudice doesn’t affect us. Racism, though, is systemic, and it is dangerous. There are things in the system that we can’t do anything about, and those are the things I have to talk to my children about.”

The Franklins were cautious to talk about race at the dinner table. They didn’t want to have the conversation too early and burden them. “They were just kids,” the Franklins explain. “We didn’t want to be too heavy too soon.”

However, Stephen was forced to address the issue when Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old, was shot and killed by a Cleveland police officer while throwing snowballs and playing with a toy gun in a local park.

“I have been used to seeing black men get killed by cops, but I’d never seen it with a kid. It was sick! America has an obsession with guns, and this kid was playing with a toy gun with his friend and now he’s dead. Sure, we all know the story of Emmit Till, but this was current and on the news, and I had to see it. It scared the hell out of me. My son was also 12 at the time. He’s an athlete so he is always in a hoodie or a jersey coming from practice, and all the sudden I have to tell him to take his hood down or change because we’re going into the grocery. It is so hard to talk about because you don’t want to kill his spirit.”

“There are things in the system that we can’t do anything about, and those are the things I have to talk to my children about,” says Stephen Franklin, here with his family.

The Franklins explained that, around that same time as a middle schooler, their son was called the n-word at his private school. The family immediately decided to pull him from the school, but the headmaster begged them to stay because “We need more people like him here.” This was another example of the pressure that society puts on their children, the Franklins explained.

“When you’re African American, you have to be twice as good. Our kids have trouble with that — we have trouble with that — it doesn’t seem fair. We put a lot of pressure on them to be the representative of our family and an entire race. People around them may only have one experience with a black person, and that is a heavy weight. My 12-year-old has to be there for the benefit of everyone else? No, we felt like he just needed to be a kid.”

What gives the Franklins hope? The call for social justice from the youth in this city and the diversity present in the current protests. “When our white brothers and sisters stand side-by-side against systemic racism, that gives us hope.”