7 minute read

triangle shirtwaist factory fire

You are my dragon. Breathe fire for me while I choke you with gasoline-streaks hands, black smoke spilling from your throat. Feeble whimpers unanswered.

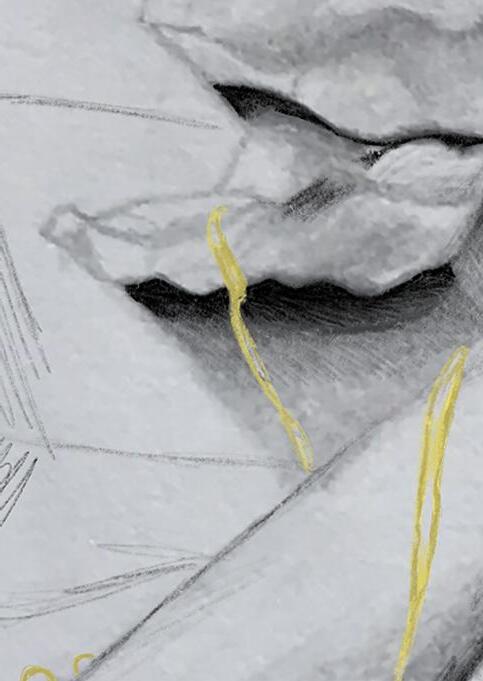

The air hums with our symphony every minute, every hour, every day, until our fingers pill and shed in strips of grey skin like powder-thin fabric. Needles pierce cotton and skin and flesh, red stipples and rivers carve treasure paths on towels — “towels” we fashion from shredded scraps rejected from unworthy stitches. Rags we press firmly into fingers then release before the wound, and our lonely fingertips, can relish the fleeting seconds locked in its embrace with the fabric.

Advertisement

Fuck! Don’t get it on the shirt! You dumbass. Pinkie back and hooked around the ring finger to hold the criminal from staining the moneymakers, as if you were a royal sipping tea with proper etiquette. Four cents for each sleeve, six for each complete shirt. My sewing machine creaking and sputtering adjacent to hundreds of others in suffocating aisles, flanked by piles of cotton and bloody “towels” that keep reminding me of the cents I’m losing with each second yelping and wiping fingers, each minute lost to cracking knuckles and stretching.

The skylines of Greenwich Village are reaching fingers of graffiti-kissed stone walls; thin wobbling trees barely buttressed by wooden bars placed by the city; tendrils of white smoke wafting from greasy food stands in nooks and alleyways. Outside the window by my teetering desk, rivulets of dew drip off of birch leaves onto the thirsting tongue of a mama squirrel— My Ma would be hungry without this job, you know? Who do you feed at home? The insanity of your audacity, the questions you dodge and the bandages that mummy your hands, your enormous pile of hemmed shirts and stitched trousers dwarfing mine. Your smirks.

Two months ago, we huddled in the supervisor’s office on the sixteenth floor, stifling coughs from dirty wisps of smoke from Dean’s fucking cesspool of an ashtray, stained gum wads interbreeding with cigarette butts and condom wrappers. We were the two veteran workers — the retention rate was low — and one of the senior sewers on the fourteenth had lost an eye to a snapped needle. One of us was due for the promotion, and when I had left the room, and the door only slightly ajar, to pant a breath of fresh air outside, I overheard your sly murmurs, “... steals shirts from the piles, when no one’s watching… I was watching… steals money from the vending machines…”

You bought me dinner last night at the stands across the street. The smoke of the grilled beef and hanging ducks — necks loose — swelled from the foil plates into my eyes, gut, lips, until I emerged dripping. Oil streaks on charred flesh, the burning almost repulsive, but not as repulsive as you. After our late shift, midnight churnings of needle and scissor, I almost went back on my word. That one lone lightbulb swinging from its detached cord on the ceiling, flickering as we squinted in the darkness at the stitches beneath our fingers, praying, cursing at any dots of red. Was it truce? You laughed when I told you Pa died four months ago when the mine collapsed onto him, the canary still singing when the speck of light above suddenly erupted into tumbling rocks. We moved to the city when they said the body was gone for good.

Your Pa was a miner too. That much you let slip, and I almost regretted my aggression.

Fuck you. When I spun around and pushed back in, Dean had already decided before I could reveal your own lowly tricks and sneaky sleight-ofhands. We use our instincts to survive, scum of earth like us. We scrape and peel the pit of the earth and ravish whatever our fingertips meet. We are a pack. When a crab climbs to the bucket brim, the tunnel’s light overflowing the unintelligent creature with hope and renewed strength, scum like you exist to drag them down. You’re filth.

I sneaked into the factory entrance on the corner of Greene and Washington Place after even the last sewing machines rode the tide to the harbor, after the last guarding crow — beady eyes and grimy beak perched on rusty windowsill, it resembles you — had closed its eyes. Moonlight tucked under the flapping collar of my threadbare coat, I sneaked gasoline gallons in two hands, bone arms creaking as dirt-dark oxfords hit concrete. The hollow frame of a door on the first floor swung, screaming, with a push of a shoulder — I slipped in before passengers peered from their carriages, urchins from their sooty alleyways. Even if they spotted me, I fear not fines nor jailtime. You see now.

Who do you work for? The desperation in your mechanical pace mirroring mine, joints and skeletal hands shaking with every turn of the sewing wheel like the thinnest violin string strung too tight — who do you struggle for? Your Ma? Wilting grandparents, a leeching sibling? Secrets veiled behind your subtle whispers behind doors, in the narrow staircase on your way up to the fourteenth, lingering by the door to the thirteenth and peering in to make eye contact for smug milliseconds.

The first and the second and the third were steeped in gasoline from ceiling to boot-trodden tobacco stains before the telltale flicker of the lights alerted me. Tattooed chap on the second floor, stumbling in before dawn to salvage hours to feed his grandmama, hollered g’morning at me as I crept down the staircase. Meathouse across the way smelling mighty strong today, he says, fingers already pushing thread through bobbin. Metal gallon cans clanking hollow behind my back, I almost laughed.

In the deep of the night, I plotted my cunning trap— a ginger cat leering from the rooftops at rat packs creeping sewage drains below.

You’re the rat.

Here’s the empty cleaner’s closet on the fourteenth. When you appeared in the morning, I swooped and gripped you with my dirty claws, pulling you in and locking ourselves into the filthiest ring fight, two animals barred in an eight-feet cage. The match had already been lit by then, the first floor simmering beneath us as we clenched each other in headlocks.

Do you think life was a game? Last week, sixteen shirts overdue and bulging eyes transfixed on the shattered clock on the wall, ticking towards one on yet another restless night, I screamed in the empty factory as I counted my pennies. Delirium, frenzy, empty gut, empty soul, my fingertip slipped — needle puncturing knuckle, and a second scream.

Unexpectedly, the next day, index finger frozen in a cast, stiff and useless, Dean brought me to the fourteenth and showed me the new empty station (the last chap? stabbed in a gang fight), and boasted the sudden raise: five cents for each sleeve, and— dresses! My grubby hands would be allowed on the dresses, full eleven cents for each garment. You had glared from your station two feet away.

The other sewers said it’s tragic. Misfortune: a finger crushed under metal, then a fall, because they didn’t see you behind me. How I had grappled helplessly in the air for the skinny railing, the wall, any tangible surface, when my patched shoes lost the staircase from the fourteen and tumbled, screaming bloody murder, down the dark drop, smashing my face into the landing on the third floor. Your quick hands and the gasp — so professional — covering your eyes in feigned shock and your two steps back. No one saw but you and me.

Now windows start to pound and people begin to scream, now a familiar sound to my ears. Only slightly muffled by the layers of walls between us and the world, they open the less-rusty windows to screech SOS, but they won’t jump. The streams of smoke flow from the ground floor to the thirteenth to here through every crack and termite hole, reaching through the slit beneath our door to warp about us. Black and magenta swirls hook around our waists, threads trapping needles, stinging eyes and choking us until we gag in our syncopated rhythm.

Every footstep is an uncertainty now, at least for the people outside our door. Walls moan and floorboards whistle in kettle-pitch falsetto. The inferno must be devouring the first, second, third, the fourth… I count the floors up to the fourteenth like coins slipping away from trembling fingers.

Was it worth it? Fuck yes. Did you guess it would be me? By your side when the ugly end greets you, the one to send you off and the one to come with you. I want to shake you until you fall limp, smash you with the cast until you beg and promise atonement in our next lives — doubtlessly conjoined for as long as we’ll reincarnate, intertwined like two braindead parasites, thinking we’re leeching off of each other when we’re killing our fucking selves.

For four days, I had laid on the damp floor of my apartment, Mother spooning porridge into my askew jaw — broken from the fall in the staircase, from your quick hands — while I cursed obscenities out the leaky window. Each day, a death toll rang from our hearts, echoing in our coinbags, now empty. By the fifth day, even the porridge and potato scraps salvaged behind the corner mart had run scarce. On the sixth, eyes rolling, head reeling, I limped down the apartment stairs, through the stumbling streets of Greenwich Village, pushed through the factory doors, gasped and cursed my way up to the thirteenth, only to discover— newly demoted. But still I had to work, have to work, food, food, food, dying…

The shaking reaches a fever pitch, the building and Earth itself threatening to fold inwards and swallow us into its flaming core. Releasing you from my grip, I clasp five fingers and stiff cast together in a gesture of serenity, the floors outside our door still buzzing with the factory rhythm in my head, even though the sewing machines have been long abandoned.

Will the buzzing ever cease? Four cents a sleeve. Five cents a sleeve. Dresses. Hems, bloody hems. Five days, no pay, and hungry stomachs collapsing onto themselves, little coal mines crushing canaries. They were so young, so innocent, left so much behind when the Gods blinked and Earth decided it would snatch their fathers away.

Ma will be lonely, but who do you care for? They will be lonely too, kneeling and convulsing in grief at the sight of smoke seeping through our shirts, ash streaks tattooing your collarbones, pouring from your eye sockets. Two mothers weeping next to dead children, so young before the light above them gave away to falling concrete.

You are my dragon. Breathe fire for me while I picture myself at the ground floor of the factory, peering up to the fourteenth to see two damned fools intertwined in bloody headlocks til the bitter end. The factory workers — the live ones — pound their windows and scream, and the brave ones leap.