4 minute read

Geometric Harmony

by Jim Neglia - Percussionist & Personnel Manager, Jacksonville Sym.

“...instrument of indeterminate pitch”

Advertisement

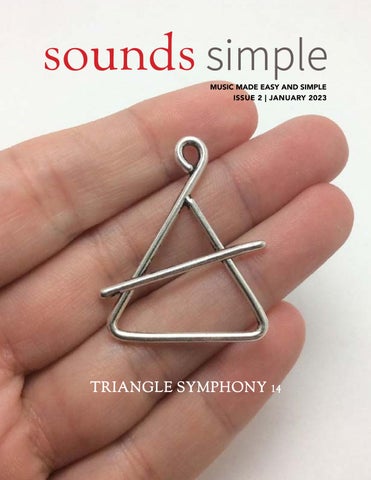

The triangle is an idiophonic musical instrument of the percussion family. It is a bar of metal, most usually steel in modern instruments, bent into a triangle shape. One of the angles is left open, with the ends of the bar not quite touching – this causes the instrument to be of indeterminate pitch. It is usually suspended from one of the other corners by a piece of thin wire or gut, leaving it free to vibrate. It is usually struck with a metal beater, giving a high-pitched, ringing tone. In folk music it is more often hooked over the hand so that one side can be damped by the fingers to vary the tone. The pitch can also be modulated slightly by varying the area struck and more subtle damping.

The exact origins of the instrument are unknown, but several paintings from the Middle Ages depict the instrument being played by angels, which has led to the belief that it played some part in church services at that time. Other paintings show it being used in folk bands. Some triangles have jingling rings along the lower side.

Although the instrument is nowadays generally in the form of an equilateral triangle, these early instruments were often isosceles triangles.

The triangle has been used in the western classical orchestra since around the middle of the 18th century. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven all used it, though sparingly, usually in imitation of Janissary bands. The first piece to make the triangle really prominent was Franz Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1, where it is used as a solo instrument in the second movement.

The triangle appears to require no specialist ability to play and is often used in jokes and one liners as an archetypal instrument that even an idiot can play. The Martin Short sketch comedy character Ed Grimley is the best-known example. However, triangle parts in classical music can be very demanding, and James Blades in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians writes that “the triangle is by no means a simple instrument to play”. In the hands of an expert it can be a surprisingly subtle and expressive instrument.

Most difficulties in playing the triangle come from the complex rhythms which are sometimes written for it, although it can also be quite difficult to control the level of volume. Very quiet notes can be obtained by using a much lighter beater – knitting needles are sometimes used for the quietest notes. Composers sometimes call for a wooden beater to be used instead of a metal one, which gives a rather “duller” and quieter tone.

When we think of steel, we often imagine tall skyscrapers and large-scale constructions – heavy industry. But in the realm of music, steel can play a more delicate role.

In comes the triangle. Remember the triangle? You may have first encountered the simple instrument in grade school, as a tinkering tool to play with for band practice. It is often disregarded as a legitimate instrument and forgotten about, but the percussive idiophone should not be taken for granted.

The Humble Triangle’s Musical Impact

Unassuming in composition (it is literally an outline of a triangle), it is one of the only percussion instruments that is made entirely out of metal. It is usually shaped from a steel bar into an equilateral or isosceles triangle, with an opening at one of its corners.

Historically, the triangle was created from both solid iron and steel rod, but is now primarily made from steel. It comes with a playing apparatus, usually a steel beater, and hangs suspended from a fishing line. The thin suspension line lets the instrument vibrate freely and create its signature noise.

The simple triangle’s sound is affected by the sizes and materials it comes in; the preferred orchestra size is between six to nine inches in diameter and played with a steel or wooden beater, which dictate a distinct note. The instrument’s tones range diversely from a shimmering trill to a more substantial, allencompassing ring, all depending on what the conductor wants.

“the difficulty and nuance in mastering triangle performance”

For a post for the Utah Symphony, professional triangle player Eric Hopkins noted the difficulty and nuance in mastering triangle performance. Most think it just requires hitting a steel triangle with a baton, but it actually takes more effort and skill than this obvious method.

It eventually evolved and transitioned into compositions by Mozart and Beethoven, and nowadays, we see it as a permanent member of complete orchestras around the world. Franz Liszt was the first to make a solo symphony featuring the triangle, as heard discreetly down below in “Piano Concerto No. 1”.

Beyond the Classics

The triangle can appear to have a difficult time fitting in next to main attraction instruments such as the violin or the piano. However, the threepointed musical underdog has traveled far from western classical music, now taking part in the folk and pop genres with its unifying sound. Both John Deacon of Queen and Joni Mitchell have featured its characteristic clang in their tunes.

In folk music, forró and rock music, the triangle is played by hooking it over the hand so that one side can be muted by the fingers to vary the tone. It is popularly used in Cajun music, where it is used as a strong beat, especially if no drums are part of the performance.

Light in Weight, Unavoidable in Sound

Without knowledge of its sensitive nature, it can be hard to take the fine triangle seriously. But by understanding that through appropriate manipulation of the instrument’s timbre and articulation, its musical elements can be conveyed with more complexity. Being especially particular to the way the triangle is handled is the key to playing it successfully.

Its steel frame gives it this unique chime, and while it does not play the most notes within a symphony, it has its virtues, particularly for its overarching tonal blending capabilities.

Triangle Basics

By Chris Wheeler