16 minute read

OUR BEAUTIFUL ANGRY RIVER... THREE LIVES-THREE STORIES

BY TONY GALLUCCI (PUBLICATIONS@YOUTH-RANCH.ORG)

It’s dark outside when Reece Zunker awakens to water rising in the bedroom of his mother-in-law, Lucy’s, home. That house is not situated where water should be coming inside for any reason; but the home is in Hunt, Texas, and the whole world will soon know that town’s being engulfed by an angry, raging river. Reece, Kerrville Tivy’s Head Soccer Coach and Football Assistant, had gone with his wife, Paula Joe, to take their son, 7-year-old, Lyle, and 3-year-old daughter, Holland, to their grandma’s house to celebrate the Fourth of July. They’d planned on family time at the river watching some fireworks. Then catastrophe struck. At 3:46 a.m. 911 dispatch received a call from Hunt, from someone with two young children panicked over water rising in their house. The call lasts 24 minutes.

At approximately 5:00 a.m., Chris Moralez, Ingram Tom Moore High School Cross Country and Tennis Coach, called ITM Athletic Director Tate DeMasco to warn him of severe flooding in Hunt, where Chris was himself awakened by rising waters. DeMasco knew what that meant. He grew up in Kerrville and has seen many a minor flood and a big one or two. He called up Assistant Football Coach Joel Hinton, and they went to work diverting traffic from the Old Ingram Loop where water was already rising, eventually swamping the historic shopping district. The high school has a population composed of a large number of students from Hunt, whose school educates children only to eighth grade. Tate was certainly cognizant of the lives upriver, as well as his home district. His children played sports with Hunt children. If you’re from here, you’d know that in this stretch of the river we’re all family.

Up where the hills rise to 2300 feet in far west Kerr County, the rains started about 9:00 p.m. on July 3rd By midnight, somewhere between 10 and 15 inches of rain had fallen. There are no static rain gauges out in that vast ranch country to give us an accurate reading. The best we can do is analyze radar signatures to estimate how much rain fell. There, in far southwest county, a high ridge determines whether water flows into the Frio River watershed or the Guadalupe. For a xeric county, it may be the richest in Texas for feeding such watersheds. In fact, seven different rivers trace part of their origins to Kerr County. Besides those two, portions of the county directly flow into the Nueces, Sabinal, Llano, Pedernales, and Medina Rivers. But on July 3rd and 4th, the heaviest rains fell on rocky ranchland that fed into the Guadalupe, the only one of those seven that actually becomes a river within the county; and boy, is it a river. Treasured for nearly two centuries as a clear, cool water source for pioneers to its modern day status as a recreational mecca bejeweled with 20 summer camps, it has no equal in Texas. Lined with thousands of towering baldcypress trees, it undoubtedly was an important indigenous lifesource for millennia before settlers first found it in the mid-1800s and set up shingle-making camps and mills, thereby becoming the first to redirect the flow of the river.

Julian Ryan’s two kids and mother-in-law-tobe appeared in his bedroom before light waking him and his fiancé, Christinia Wilson, mother of the children. When they awoke and checked to see what the kids wanted, they found them standing in ankledeep water. Living not far from the Old Ingram Loop shopping district and 200 yards from the everyday channel of the Guadalupe, their home was somehow about to be swallowed up by that very river. Julian was a young man, just 27, but he knew enough about this old river to know there was no time to waste. By the time they were able to execute a move, Wilson said the water was over their hips. Frantic to get the family out of the house they tried the front door, but water came pouring in. His sister and her family live next door and from windows they shouted at each other through the rain. Connie Salas, his sister, asked Julian if he was okay. “Yes,” he shouted back, “Are you okay?”

“I’m scared,” were Connie’s next words. And his? “Me too.” Desperate, he broke a plate glass window so he could get the family and their pets to the roof of their mobile home. But in breaking through that pane a shard of glass sliced his arm open, cutting deep into an artery. Still, he followed his family out and mustered the strength to get them on the roof, and then boosted himself up. He was bleeding profusely. 911 was called.

With nowhere to go, Zunker also hoisted his mother-in-law, his wife, and two kids to the roof of the house before climbing up himself. It was a refuge from the water, but not from danger. Folks on higher ground watched as the house shifted, then detached from its foundation, no match for the force of the then nearly forty-foot high river roaring at 30 miles an hour and carrying 75-foot baldcypress trees ripped from the riverbanks. It was just too much. They were soon battered by tree limbs and debris. Reece lay across his family to protect them from whipping branches, but Paula Joe’s mother, Lucy, unable to keep her grip, slid off the roof. Miraculously she grabbed a tree above the waterline from which she was later rescued. Neighbors watched the family, Reece, Paula Joe, Lyle, and Holland bob downriver on the roof.

We now know what 10-15” of rain falling fast on the Frio Divide will do to everything downstream. Constant heavy rainfall until after 3:00 a.m., coupled with moderate rain continuing until late in the morning, was a recipe for a disaster we locals have pondered, but never really fathomed. At the last draw before you arrive high on the Frio Divide, normally just a hardly discernible low spot, drift was left on the top rung of an eight foot high game fence. The water barreling through there was likely higher. That draw? It’s 14 river miles above Camp Mystic, now a historical datapoint for the loss of 28 children and staff, including the camp’s longtime director and camp owner, Dick Eastland. That’s 14 miles of rain gathering by the acrefoot and picking up proverbial steam before hitting the River Inn Resort and Mystic.

Ground-zero of flood destruction and death, if you want some kind of narrower definition, stretches 16 river miles from River Inn just above Mystic to just below Ingram. Most all of the 119 lives lost in Kerr County came from that stretch. Some bodies were retrieved in Comfort, 37 miles and four substantial dams downstream. Mystic got massive attention from the national press; rightly so, because of the stories resulting from the loss of so many young girls. The Eastland family, who owns Mystic, have myriad connections to this story. The Eastland sons, all four of them, played sports at Tivy High School; the oldest, Richard, having played soccer on the first Tivy team to win district and advance in the playoffs. Son James, who played football for the Antlers, was a groomsman at Tate and Melissa McGehee DeMasco’s wedding. Now there are Eastland grandkids playing for Tivy. Our tiny world comes full circle.

By the evening of day one, Tate was directing helicopters to safe landings on the ITM football practice field, delivering rescued Camp Mystic campers and staff from some ten air miles upriver. DeMasco appointed folks to deal with incoming campers, liaised with staff members to insure everyone’s needs were taken care of, and then set about to find as many ways possible to make himself useful. On day two, he found his way to City West Church, and there ran into Tim Thomason, a fulltime school supporter whose daughter played sports at ITM, who admonishes everyone to love others and runs a food bank. Together they got to work with Mercy Chefs, the biggest, and now, a month later, the longest-running supplier of meals to emergency responders, victims, and volunteers. DeMasco soon had his entire coaching staff and athletes out delivering meals up and down the river in Kerr County, the entire length of which, 60 river miles, was devastated by the flood.

The river was merciless. Below Mystic next came Camp Heart O’ the Hills, which suffered the most structural damage and thankfully was not in session. Their beloved director, Jane Ragsdale, was lost trying to save her staff. Then around the bend was Crider’s Rodeo and Dancehall, where owners, the Moore family, had been working for a year preparing to celebrate the Rodeo’s 100th Anniversary. On July 4, 1925, the Crider family put on a rodeo to benefit the Hunt School PTA. They’ve never missed a year. This year’s big event was set for the evening of the 5th, but flooding wiped that out and damage cancelled the rest of the season at this cherished community gathering spot. The river slammed onward unrelenting. The vacation lodges at Casa Bonita were wiped clean off their foundations. Next to be hit hard was Hunt, sitting just above the convergence of the two upper headwaters forks of the Guadalupe. The river paid little heed to the channels there, swamping the area from both directions, with a "wall" of water that is estimated to have reached 55 to 60 feet where the canyon narrows. The Hunt Post Office disappeared, and only a couple of rock walls remain of the storied Hunt Store, the other community gathering spot in west Kerr County. The river gauge at Hunt Crossing, where the valley widens, a quarter-mile above the confluence of the forks, measured the South Fork crest at 37.52 feet, the highest ever recorded there, besting the “Big Daddy” floods of 1932 and 1987. From there the raging river ravaged homes in the Bumble Bee Hills neighborhood on its way to Ingram where it swept away every RV and camper parked in the HTR Campground, and many of the folks sleeping in them. Then it barreled on to River Run, where Julian Ryan’s family would soon be scrambling to safety.

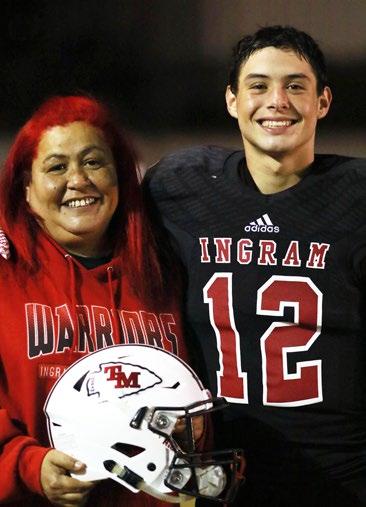

By the time an ambulance crew was able to get to the park it would be to no avail. They weren’t able to reach Julian’s family for seven hours. He’d managed to say to his fiancé and kids, “I’m sorry. I’m not going to make it. I love you,” and bled out before any lifesaving interventions could be administered by medics. The rest of the family held on long enough for the waters to recede. Neighbors helped them escape to higher ground. Julian had been a star multi-purpose football player for the Ingram Tom Moore Warriors nine years earlier, helping set them up for a future trip to the playoffs. He made the team better just by his presence, but football’s not what he’ll be remembered for. Julian was one of those guys who was never, ever, without a smile or a helping hand. He ‘lit up a room’ as they say. Those kids were his life force, and his funeral was a testament to how much he loved and doted on them. He was a son, brother, father, partner, and best friend. Julian’s was the second service to take place in our community after the flood; the first having been earlier in the day for celebrated spitfire Renee Smajstrla, the only Mystic girl who was also a local child. Julian was buried in the Garden of Memories in Kerrville in the shade of a live oak with a red-tailed hawk floating overhead.

Tate was there with Mercy Chefs and Thomason’s Blind Faith Foundation working long days every single day right up until he and his staff had to drag pylons and water coolers and training tables out to the football field for the opening of football practice the first full week of August. There, they got to admire the school’s first ever artificial turf, newly installed after the flood, as well as a brand new track. ITM is Tate’s first high school head coaching job, but his resume is filled with plum coaching positions. He has tackled everything from running backs coach to offensive coordinator at San Antonio big schools Jay, Roosevelt, MacArthur, Brandeis, Madison, and Reagan before returning to his home county, where he promptly established a new culture and cultivated a legion of loyal parents and fans. His impact is not limited to football. He is the consummate all-sports AD. During the 2024-25 school year, for the first time in school history, every ITM sport made the playoffs. The football team made the playoffs for the first time since the era of Julian Ryan. And this year, on the first day of fall practice, over 80 kids suited up in shorts and helmets. Stunning for a small 3A school in the midst of an overwhelming tragedy.

It took a few weeks for all the Zunkers to be found, the children lastly so, and the finality that came with it hit the town of Kerrville hard. A memorial service was held August 4th at Schreiner University’s Event Center, filled with 1500 family, friends, and players. Tyler Krug and Rebecca Hagar, friends of Reece and Paula Joe since their hometown school days, gave testaments to the depth of friendship they engendered, the good times had, and the lasting legacy they leave. Tivy High School Principal Rick Sralla, who had once been Coach Sralla, told about the pranks he and Reece played on each other in the locker room, and the nervousness Reece navigated when asked to give a warmup speech to the varsity football team for the first time. Zunker resorted to the “Burn the Boat” speech, and in Sralla’s rendition he nailed it. Three players from Reece’s 2019 Regional qualifiers, Jasen Zirkel, later a collegiate player, Tivy’s all-time leading scorer Alexsandro Gutierrez Resendiz, and First Team All-State defender Caleb Kissinger, gave deeply moving speeches about the mark he left on their lives, with impacts way beyond coaching: mentor, classroom teacher and inspiration, surrogate father, even giving them jobs after graduation in his construction side-gig. Each player spoke fondly of Paula Joe and the kids, as any player of Reece’s was also part of his family. Reece was named back-to-back Texas Association of Soccer Coaches Coach of the Year in 2018 and 2019, and later named both Tivy High School’s and the Kerrville Independent School District’s Teacher of the Year. As the memorial came to a close, Kissinger told a story – a few days after the flood he was alone, ‘talking’ to the Zunkers, and he asked for a sign they were still with us. A pair of doves flew over, circled, and landed a few feet away. “From that point forward, I knew they were still here, listening . . .”

Floodwaters left debris on the chainlink fence surrounding Warrior stadium, knocked out the entrance gates, and left literal tons of wood debris and house detritus, battered cars, and boats all around. Majestic baldcypress trees lining the river loom just south of the field. Visible from the stadium stands, they now look like they’ve been mowed down. But the river itself didn’t get quite close enough to keep the upcoming football season from starting on time. It’s a rare silver lining in a community stretching from Hunt to Ingram that desperately needs to heal, and will finally begin to under the sheltering umbrella of Tate DeMasco. “We’re over ‘sad’,” Tate told Texas Football. “It’s our kids. It’s our community. We owe it to everybody who comes and watches us play games and supports our school to be there for them in a time of need.”

For those wanting to help, here are ways to contribute: https://www.communityfoundation.net/ https://nbcommunityfoundation.org/communitybetterment/

The Community Foundation of the Texas Hill Country has set up a Flood Relief Fund that has already disbursed funds to help repair damage to Ingram Tom Moore High School property, as well as to many other local funds providers dedicated to healing the community.

The New Braunfels Community Foundation has set up the Zunker Family Foundation to contribute to causes dear to Reece’s and Paula Joe’s hearts.

Julian was celebrated across the world as a hero. Due to the incredible generosity of many donors, including some national celebrities, a GoFundMe page for his family overflowed and was closed by his family in order that funds could be diverted to other families in need. Donations may be made to other flood victims in Julian’s name.

Photos by Tony Gallucci

Author, Tony Gallucci, coached soccer at Tivy High School from 1986 to 1997 and was elected TASCO Vice President in his final year. He has been a lifelong Tivy fan since, but was especially thankful to know Reece Zunker, whose coaching style and impact he greatly admired. They talked often about the game. During Tony’s time at Tivy, Tate DeMasco was a student-athlete there, as were five other current ITM coaches. Tate’s dad, Coach Phil DeMasco, was his supervisor. Up through 2006, his summers were spent at Camp Rio Vista in Ingram, a camp spared disaster only by virtue of having had their session closing day on July 3rd. His connection to area camps runs deep – he coached a couple of those Mystic Eastland boys.

“The people of this community are an amazing tapestry,” he said. “We’re all family.” Tony is now in charge of communications at the Hill Country Youth Ranch, an orphanage in Ingram that escaped flood damage or danger. He spends his off time as a sports photographer covering every school directly impacted by the flood: Hunt, Ingram, Harper, Tivy, Our Lady of the Hills, Center Point, and Comfort. Julian Ryan was once a constant presence in his photos. Fifteen of Tony’s friends were lost in the flood.