4 minute read

Further study in 1.4

Barbarians or noble savages?

Source 35

Tell me, what gives you the right to treat these Indians so cruelly? What gives you the right to wage such detestable wars against these people who lived quietly and peacefully in their own lands?

Paraphrased from: Antonio de Montesinos (1550), quoted in Mark Burkholder and Lyman Johnson’s Colonial Latin America, 1990.

Another priest, Bartolomé de las Casas, also spoke up for the indigenous population. This monk travelled through Hispanic America from 1502. He protested against the mistreatment of the indigenous population.

Source 36

There is no nation – no matter how primitive, uncivilized, barbaric, savage and even violent – who cannot be persuaded to live a good life with love, kindness and generosity. For all people are human beings. In their creation all men are equal.

Paraphrased from: De Las Casas (1550), based on quote in Michael Wood’s The Conquistadors, 2000.

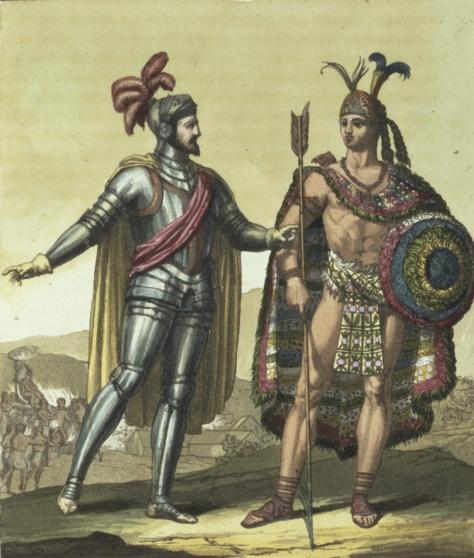

source 34

A conquistador and an indigenous American stand side by side in a classical pose. Picture from the nineteenth century.

Debate about the indigenous peoples

News of the discoveries brought back by the explorers was greeted with delight by the curious Europeans. But the cruelty the conquistadors used to expand their world, could not always count on sympathy. Philosophers and theologians began to think about the treatment of foreign peoples in the New World. Was it true that the colonies had been in a lower ‘natural’ state before the arrival of the Europeans? Did the indigenous peoples really have to be ‘cultivated’ by means of science, technology and Christianity? And did this have to be accompanied by cruelty? This soon led to a debate among Spanish thinkers, which spread across Europe.

In 1511 the monk Antonio de Montesinos gave a powerful sermon in front of the Spanish conquistadors in Santo Domingo in which he spoke up on behalf of the indigenous Americans and accused the Spaniards of inhuman behaviour.

De las Casas travelled to Spain and argued his case at the court of Charles V with the scholar Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, a man who took it for granted that the indigenous Americans were inferior.

Source 37

The Indians did not live in an idyllic world before the Spaniards came. They continually conducted ferocious wars against each other and ate those who were slain. I therefore believe that these are beings of a lower order whose habits and characters are barbaric and uncivilized, and that this was so before the Spaniards arrived. Not to mention their religion and the sacrifices (human hearts) with which they worship the devil. There is no doubt about the fact that these peoples, so uncivilized and barbarous, have been justifiably brought under the rule of Spain.

Paraphrased from: Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda (1550), based on quote in Michael Wood’s The Conquistadors, 2000.

Another voice became involved in this discussion: Wamam Poma, an indigenous American who tried in vain to send the following text to the Spanish king.

Source 38

Although the Incas may have begun as barbarians, they have developed over a long time. Your Majesty, imagine being an Indian in your own country and being forced to carry a load like a horse and being driven along with blows from a stick. Imagine being called a dirty dog. Imagine having your women and your property taken away for no reason. What would you do in that situation? In my opinion, you would gladly eat your tormentors alive.

Paraphrased from: Wamam Poma (1613), based on quote in Michael Wood’s The Conquistadors, 2000.

Humanists on the indigenous Americans

The sixteenth-century humanist Michel de Montaigne wrote about all kinds of topics he considered to be important. At the court of the French king, he met three indigenous Americans who had been taken to France as prisoners. Through an interpreter he was able to ask them all kinds of questions. In his essay On Cannibals, he described not only this encounter but also the facts once told him by a sailor. He came to the conclusion that the indigenous Americans were not barbaric, but were instead a kind of noble savages.

Source 39

These peoples seem to me, then, barbaric in that they have been little refashioned by the human mind and are still quite close to their original naiveté. They are still ruled by natural laws, only slightly corrupted by ours. They are in such a state of purity that I am sometimes saddened by the thought that we did not discover them earlier, when there were people who would have known how to judge them better than we.

Paraphrased from: Michel de Montaigne, Essays, 1580.

De Montaigne also stated his views about the attitude of the West towards the indigenous Americans.

Source 40

I do not find that there is anything barbaric or savage about this nation [...] unless we are to call barbarism whatever differs from our own customs. Indeed, we seem to have no other standard of truth and reason than the opinions and customs of our own country. There at home is always the perfect religion, the perfect legal system; the perfect and most accomplished way of doing everything.

Paraphrased from: Michel de Montaigne, Essays, 1580.

Another humanist, the Flemish Justus Lipsius, did not agree with Michel de Montaigne.

Source 41

In the past, the Romans imposed an oppressive yoke on the Earth, but with a beneficial outcome, because it drove out the spirit of barbarism as the sun drives out the darkness before our eyes. I dare to predict that the same will happen with the New World, which the Spaniards with beneficial cruelty have made an emptiness to populate and develop her from now on. Thus God governs the plantation which is our wide world.

Paraphrased from: Justus Lipsius, quoted in Robert Lemm’s Ochtend van Amerika (1989).