8 minute read

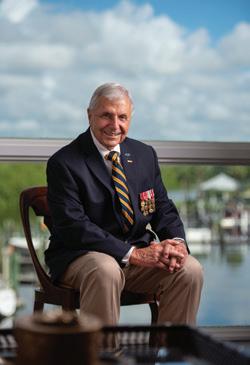

Mission Driven: Shell Point Resident Jim Stapleton Remains an Army Man at Heart By Nick Fortuna

Mission Driven

After a lifetime of service, Shell Point resident Jim Stapleton remains an Army man at heart

By Nick Fortuna

Even now, 26 years after he retired from the U.S. Army, Col. Jim Stapleton is protecting his men.

Back in 1967, Stapleton led a rifle company ranging from 90 to 110 men on a seven-month trek through the Central Highlands of Vietnam, and he didn’t lose a single man during more than 30 combat engagements. Fast forward to this spring, and Stapleton’s mission wasn’t nearly as challenging or perilous, though it still was important.

Stapleton coordinates the veterans group at Shell Point Retirement Community in Fort Myers, where he has lived with his wife, Carolyn, since 2018. On a morning in March, just as the coronavirus pandemic was beginning to shut down public life, Stapleton could be found sitting on a bench outside the community’s meeting hall.

A meeting of the veterans group had been canceled, and Stapleton wanted to make sure none of its 140 members showed up and socialized in tight quarters. It’s well documented that this particular virus is especially hard on seniors, so Stapleton took force-protection measures, just as he had five decades ago overseas. It was an example of Stapleton living according to his personal motto: “Mission first, people always.”

Stapleton seemingly was destined to be a soldier. “I was born in Army diapers,” he said with a laugh. He was born at Fort McPherson in Atlanta, where his father, Army surgeon James “Buck” Stapleton, was stationed.

The family moved around a bit before Jim’s dad was assigned to West Point to run its hospital. A teenaged Stapleton quickly established friendships with neighbors who intended to enroll in the Military Academy, solidifying his future plans. He would enroll and play for West Point’s lacrosse team before graduating as an infantry officer in 1964.

Stapleton had known friends and fellow West Point cadets who died in the Vietnam War, but after graduating, he was determined to do his part.

“There wasn’t fear,” he said. “Nobody wanted to miss the opportunity to command a company or a rifle platoon, and people were raring to go. We all wanted to get our chance.”

Stapleton joined the 4th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, near Tacoma, Washington, where he spent nine months preparing to deploy. To get acclimated to the terrain in Vietnam, the soldiers trained in the dense forests, mountains and foothills surrounding Mount Rainier. Proclaimed battle ready, the division embarked on a 16-day transport to Vietnam aboard the U.S. Navy ship Gen. Nelson M. Walker, arriving in August 1966. The typical tour in Vietnam was 12 months, but Stapleton served for 28 consecutive months, spending his 25th birthday in the Central Highlands and his 26th in Saigon. Amid the harsh reality of war, Stapleton also had leisure on his mind. By extending his tour twice, he earned an additional 60 days of rest and recuperation and a chance to spend time in Australia, Hong Kong and Taiwan. His bravery had its benefits.

“It wasn’t all bad,” he said of extending his tour.

A Disciplined Approach

Stapleton began his tour as a rifle company executive officer, but was promoted to captain a few months later and was made the commander of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment. But the circumstances of the promotion were more somber than celebratory. The man Stapleton was replacing had just been killed in action, presumably by sniper fire while checking to see why progress had stalled at the front of the company.

“When an officer got killed, it was usually when he was doing something that he shouldn’t have been doing,” Stapleton said. “He was somewhere that he shouldn’t have been. That obviously weighed heavily on me before I took over the company.”

Early in his tour, Stapleton noted that the commanding officer routinely waited until late afternoon to order his soldiers to dig in for the night, leaving them with little time to set up their overhead cover. Consequently, some soldiers were killed or injured in mortar attacks. Now in command, Stapleton was determined not to repeat that mistake, so he established a routine centered around maximum force protection. Stapleton’s rifle company covered several miles a day through jungles, woods, mountains and fields during its seven-month journey through the Central Highlands. They typically would engage in search-and-destroy combat operations until about 2 p.m. before beginning to settle in for the night—establishing a perimeter, erecting structures for overhead cover and manning listening posts. Artillery support from the Army and aerial support from the Air Force were always on call. Soldiers at listening posts were relieved every few hours to reduce the chance that they would fall

asleep and leave the company vulnerable to ambush. In the morning, patrols were sent out to ensure that the path ahead was clear and that the company hadn’t been surrounded overnight.

“I think a large part of our success stemmed from the fact that we stopped early every day,” he said. “We never let our guard down. I also had a crackerjack electrical engineer who was my forward observer, and he could do magic calling in artillery, so while we were patrolling, we would call in artillery rounds so we knew where we were; we didn’t have to rely on our poor navigation in those days before GPS.”

Subsequently, Stapleton was chosen to be an aide-de-camp to Lt. Gen. William “Ray” Peers, best remembered for leading the Peers Commission investigation into the My Lai massacre and other war crimes in Vietnam. It was during this time in 1968 that the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese launched the second Tet Offensive, the surprise attack on U.S. forces and the South Vietnamese.

The offensive, timed to coincide with the Tet holiday, or Vietnamese new year, took aim at more than 100 cities and towns and was the largest military operation conducted by either side at that point in the war.

Two weeks into the offensive, the Pentagon estimated that about 33,249 enemy combatants had been killed, with another 6,000 wounded. The U.S. and South Vietnamese had seen about 3,470 soldiers killed and another 12,062 wounded, with Americans accounting for about one-third and one-half of those figures, respectively. The Tet Offensive marked a turning point in the American public’s support for the war and led renowned journalist Walter Cronkite to conclude that the U.S. was mired in a stalemate.

Stapleton spent the tail end of his tour as a battalion adviser with the Vietnamese Airborne Division, one of the elite fighting forces in the South Vietnamese army.

Success on Two Fronts

Of course, the war would end eventually, but Stapleton’s service to his country was just beginning. He would remain on active duty until retiring in 1994. He taught physical education at West Point before becoming an aide to Gen. Sam S. Walker, the Military Academy’s commandant of cadets. Subsequent assignments would send him to Germany and Italy to train and command a battalion and a brigade, and to Turkey and northern Iraq to help protect the Kurds from Iraqi aggression during the first Gulf War.

Stapleton’s military career ended right where his life had begun: at Fort McPherson, where he served as Gen. Colin Powell’s staff coordinator for Forces Command (FORSCOM), the largest Army command, consisting of more than 750,000 active-duty, Reserve and National Guard soldiers.

Success followed Stapleton into civilian life as he and his family remained in Atlanta. He joined the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games as director of logistics for the athletes’ villages, helping the city prepare for the 1996 event. He later was a vice president for the National Linen Service and Allied Automotive Group before becoming a consultant, helping to turn around and launch businesses.

Stapleton also served on the boards of the Atlanta Food Bank, Atlanta Restaurant Council, Atlanta City Sales Club, Veterans Upward Bound, U.S. Army War College Foundation and the West Point Society of Atlanta.

“It was a storybook military career, followed by 24 years of a storybook career as a civilian,” Stapleton said.

Enjoying Shell Point Retirement

Stapleton and his wife Carolyn will celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary next year, but they’ve known each other far longer than that. With their fathers both serving at West Point and their mothers working in a thrift shop there, the two were friends in high school. Just like Stapleton, Carolyn’s first husband served as a rifle company commander in Vietnam, but he was killed in action. Five years later, she married Stapleton, and he eventually adopted her two children. The couple now has seven grandchildren and three greatgrandchildren.

These days, the Stapletons are enjoying retirement at Shell Point, and Jim shows no signs of slowing down, despite a bout with head and neck cancer about 14 years ago. He and his wife volunteer to deliver mail twice a month to residents of the Larsen Pavilion, an assisted-living and rehabilitation facility, and are on the social and welcoming committees for Harbor Court, their neighborhood subdivision. They also are active in their Catholic church, and Jim is in the Knights of Columbus.

“We studied lots of retirement communities, and Shell Point beat out the competition hands down in terms of being the best place to live,” he said. “I tell people this is like living in a top-tier timeshare unit 365 days a year. I can’t think of a better place to be.”