39 minute read

ABSTRACTS

Ethical challenges posed by advanced veterinary care in companion animal veterinary practice

Advanced veterinary care (AVC) of companion animals may yield improved clinical outcomes, improved animal welfare, improved satisfaction of veterinary clients, improved satisfaction of veterinary team members, and increased practice profitability. However, it also raises ethical challenges. Yet, what counts as AVC is difficult to pinpoint due to continuing advancements. We discuss some of the challenges in defining advanced veterinary care (AVC), particularly in relation to a standard of care (SOC). We then review key ethical challenges associated with AVC that have been identified in the veterinary ethics literature, including poor quality of life, dysthanasia and caregiver burden, financial cost and accessibility of veterinary care, conflicts of interest, and the absence of ethical review for some patients undergoing AVC. We suggest some strategies to address these concerns, including prospective ethical review utilising ethical frameworks and decision-making tools, the setting of humane end points, the role of regulatory bodies in limiting acceptable procedures, and the normalisation of quality-of-life scoring. We also suggest a role for retrospective ethical review in the form of ethics rounds and clinical auditing. Our discussion reinforces the need for a spectrum of veterinary care for companion animals. AQuain1,MP Ward1,SMullan2.Animals. 2021; 11(11):3010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113010 1 Sydney School of Veterinary Science, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 2 School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

Advertisement

Metagenomic investigation of potential abortigenic pathogens in foetal tissues from Australian horses

Background: Abortion in horses leads to economic and welfarelosses to the equine industry.Most cases of equine abortions are sporadic, and the cause is often unknown. This study aimed to detect potential abortigenic pathogens in equine abortion cases in Australia using metagenomic deep sequencing methods. Results: After sequencing and analysis, a total of 68 and 86 phyla were detected in the material originating from 49 equine abortion samples and 8 samples from normal deliveries, respectively. Most phyla were present in both groups, with the exception of Chlamydiae that were only present in abortion samples. Around 2886 genera werepresent in the abortion samples and samples from normal deliveries at a cut off value of 0.001 per cent of relative abundance. Significant differences in species diversity between aborted and normal tissues was observed. Several potential abortigenic pathogens were identified at a high level of relative abundance in anumber of the abortion cases, including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus, Pantoea agglomerans, Acinetobacter lwoffii, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Chlamydia psittaci. Conclusions: This work revealed the presence of several potentially abortigenic pathogens in aborted specimens. No novel potential abortigenic agents were detected. The ability to screen samples for multiple pathogens that may not have been specifically targeted broadens the frontiers of diagnostic potential. The future use of metagenomic approaches for diagnostic purposes is likely to be facilitated by further improvements in deep sequencing technologies. RAkter12,C M El-Hage1,F M Sansom1,J Carrick3,JMDevlin#1 , ARLegione#4 BMC Genomics.†2021 Oct 2;22(1):713.Rdoi: 10.1186/s12864021-08010-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-08010-5 1Asia Pacific Centrefor Animal Health, The Melbourne Veterinary School, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, 3010, Australia. 2 Department of Medicine (Royal Melbourne Hospital), The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, 3010, Australia. To page 30 Public concern for the welfare of farm animals has increased over recent years. Meeting public demands for higher animal welfare products requires robust animal welfare assessment tools that enable the user to identify areas of potential welfare compromise and enhancement. The Five Domains model is a structured, systematic, and comprehensive framework for assessing welfare risks and enhancement in sentient animals. Since its inception in 1994, the model has undergone regular updates to incorporate advances in animal welfare understanding and scientific knowledge. The model consists of five areas, or domains, that focus attention on specific factors or conditions that may impact on an animal's welfare. These include four physical/ functional domains: nutrition, physical environment, health, and behavioural interactions, and a fifth mental or affective state domain. The first three domains draw attention to welfare-significant internal physical/functional states within the animal, whereas the fourth deals with welfare-relevant features of the animal's external physical and social environment. Initially named "Behaviour" Domain 4 was renamed "Behavioural Interactions" in the 2020 iteration of the model and was expanded to include three categories: interactions with the environment, interactions with other animals and interactions with humans. These explicitly focus attention on environmental and social circumstances that may influence the animal's ability to exercise agency, an important determinant of welfare. Once factors in Domains 1-4 have been considered, the likely consequences, in terms of the animal's subjective experiences, are assigned to Domain 5 (affective state). The integrated outcome ofall negative and positive mental experiences accumulated in Domain 5 represents the animal's current welfare state. Because the model specifically draws attention to conditions that may positively influence welfare, it provides a useful framework for identifying opportunities to promote positive welfarein intensively farmed animals. When negative affective experiences are minimised, providing animals with the opportunity to engage in species-specific rewarding behaviours may shift them into an overall positive welfarestate. In domestic pigs, providing opportunities for foraging, play, and nest building, along with improving the quality of pig-human interactions, has the potential to promote positive welfare. NJKells1.Animal. 2021 Oct 22; 100378.†https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2021.100378 1Animal Welfare Science and Bioethics Centre, School of Veterinary Science, Massey University, Private Bag 11-222, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand. Electronic address: N.J.Kells@massey.ac.nz.

The Five Domains model and promoting positive welfare in pigs

A method for assessing sustainability, with beef production as an example

Acomprehensive approach to decisions about the use of land and other world resources, taking full account of biological and other scientific information, is crucial for good decisions to be made now and in future. The sustainability of systems for producing food and other products is sometimes assessed using too narrow a range of component factors. A production system might be unsustainable because of adverse effects on a wide range of aspects of human welfare, animal welfare, or the environment. All factors should be included in sustainability evaluation, otherwise products or actions might be avoided without adequate consideration of key factors or of the diversity of production systems. A scoring method that is based on scientific information and potentially of general relevance is presented here, using beef production as a example with a review of each of its sustainability components. This includes an overall combined score and specific factors that make the system unacceptable for some consumers. The results show that, in this example, the sustainability of the best systems is very much better than that of the worst systems. By taking account of scores for a wide range of components of sustainability To page 30

Nicholas Kannegieter

Following his 1984 Sydney University graduation, Kannegieter spent a year at Camden completing an intership then four years at New Zealand’s Massey University completing aResidency in Equine Surgery and a PhD in laryngeal hemiplegia. He obtained Fellowship of the ACVSc in 1990. Kannegieter spent six years at Sydney University as an Equine Surgeon before moving into private consultancy. He now works with Hadley Willsallen, also a specialist Equine Surgeon. Kannegieter has had places on AVA and Equine Veterinarians Australia (EVA) executives, and often appeared as an expert witness for Guild Insurance. He presented the Distance Education course in Equine Surgery for many years for CVE and was appointed Adjunct Associate Professor at Charles Sturt University in 2010. Kannegieter spent 11 years presenting a weekly vet program on Racing Radio 2KY (now Sky Sports Radio) discussing veterinaryproblems and issues in the racing industry. He has also published scientific papers along the way. Kannegieter’s time is spent in 22 equine hospitals throughout Australia. He has travelled to Turkey on several occasions to teach Jockey Club of Turkey vets how to perform equine surgery and lameness exams.

Equine upper limb fractures - can any be saved?

Equine upper limb fractures present a major challenge to the equine clinician. Horses, and owners, are often presented in severe distress and the veterinarian is faced with a very difficult situation in which rapid decision making is often required. Despite a very poor prognosis being associated with certain upper limb fractures others can be successfully managed depending on a number of issues.

One of the most important issues with any fracture is the degree of stability present. Many upper limb fractures can have a high degree of stability despite having quite dramatic radiographic findings and this stability greatly assists the healing process. For such horses, despite presenting with severe lameness, attempts should be made to manage the case in the short term, using appropriate analgesics and confinement, until an accurate diagnosis and prognosis can be obtained. Unstable fractures generally present with severe distress and rapidly deteriorate so that the veterinarian has verylittle time for decision making or obtaining second opinions. Stability is the most crucial aspect of any fracture repair process.

The age, size and temperament of the horse are also factors determining survival rates. Younger and smaller horses have a much better prognosis due to faster healing and importantly less weight on not only the fractured limb but also contralateral limbs. Horses with a poor temperament are far less likely to tolerate longer term treatment, in particular full limb casting and slinging, which require ahigh degree of cooperation from the patient.

There is a great variety of potential fracture locations and configurations. One advantage that upper limb fractures have over lower limb fractures is that many of them have far greater soft tissue support and protection. While an extensive muscle covering may complicate surgical access it can also provide some stability. The extensive soft tissue covering also means that less fractures become compound fractures. Unfortunately any compound fracture has a greatly decreased chance of survival due to the much higher risk of contamination and infection associated with open wounds, particularly if internal fixation is utilised. Bone has a poor blood supply at the best of times so that traumatised and contaminated bone becomes a haven for bacterial proliferation. Once infection becomes established in equine fractures then management and resolution can be extremely challenging, expensive and often unrewarding.

Unfortunately the finances of the owner are also a major contributing factor to survival rates. There have been great advances in equine fracture management and repair however this can come at considerable cost with no guarantee of a successful outcome. Even those fees covered by equine insurance can be rapidly depleted so owners need to be fully advised on the potential costs before commencing any treatment and should be regularly updated.

Conservative treatment or surgery?

Conservative treatment has the benefit of greatly reduced costs compared to surgery as well as decreased complications. There are afew issues to consider.

■ All fractures want to heal

The natural reaction to any trauma to bone is a response by the body to attempt to heal. This involves laying down new bone which firstly provides stability and then a more rigid repair.

■ All fractures should eventually heal

Given time in the right conditions all fractures would eventually, in theory, heal. The aim of conservative therapy is to maximise the potential to heal which is primarily achieved by minimising movement at the fracture site and ensuring no infection is present.

■ Horse may fails before fracture healing can occur

Unfortunately in equine patients is often the horse that fails first before the fracture can heal. This is a direct result of the size of the horse and the weight this often puts on contralateral limbs. The difficulty in achieving good stability at fracture sites is also a major complicating factor. The very high risk of laminitis in the contralateral limb must be stressed to owners and they should be advised that it can happen verysuddenly and at any time during the treatment period, almost invariably with a fatal outcome.

■ How long is it humane to continue treatment?

The welfare of the horse must always be the first priority. Pain management of horses with upper limb fractures can often be difficult however the aim is that sufficient appropriate analgesia can be given to ensure the horse is sufficiently comfortable and coping with the degree of pain inevitably associated with fracture healing. If the horse continues to eat well, maintain adequate condition and appears bright it would seem reasonable to continue treatment. One of the first signs of the horse becoming more comfortable with the fracture is that it will be able to lie down regularly. Providing good flooring and bedding is essential as regular periods of recumbency can greatly relieve the stress on contralateral limbs. Concrete surfaces in stables, while very practical in many ways, may not be the best flooring for a horse recovering from afracture. In my experience horses rarely exacerbate the fracture by getting up or down when they are ready to do so. Cross tying of horses to prevent them from lying down is often advocated as part of the conservative management of equine fractures. It is not something I recommend as I have found it to be of little or no value and may actually compromise the longer term outcome.

Surgery

Surgery can potentially add tens of thousands of dollars to the treatment cost and is only really indicated in very select cases of upper limb fractures. Surgical access is hindered by the soft tissue covering of the upper limbs while the structure and shape of the bones, which results in extreme and complex mechanical forces, are not conducive to successful internal fixation. The risk of sepsis, even in closed fractures, is incredibly high and can compromise the outcome despite technically excellent surgical repairs. Sepsis can have a slow and insidious onset which results in a steady increase in costs mirrored by a steady decrease in prognosis for survival.

There have been good increases in fracture repair technology over the years, the latest being locking screw plates, as well as in anaesthesia and analgesic techniques, so that fractures that may not have been repairable previously may have a better prognosis today. Despite this surgical repair of upper limb fractures is a major challenge and not always the best option for some cases.

Surgery will usually greatly hasten the time taken for resolution of the problem, one way or another.

Scapula

Fractures of the scapular are not common. Most often the supraglenoid tubercle is fractured resulting in alarge loose and displaced fragment with an intra-articular component. While several techniques are described for internal fixation of these fractures, they are better removed. The main difficulty with internal fixation is getting perfect alignment on the articular surface, which is incredibly difficult to do due to the size of the fragments and extensive soft tissue attachments as well is the poor surgical exposure. Further screw placement and holding capacity is compromised by the size and location of the fracture and the structure of the scapular. Internal fixation has a high failure rate, high complication rate and a high incidence of long term DJD as the articular component is impossible to accurately align. It is not recommended.

If surgery is performed a large incision is made over the supraglenoid tubercle and sharp dissection continued for 10 cm or more down to the fragment. The fragment can be quite large, often 10 - 12cm in diameter.

Key issues to consider for long bone fractures: -Stability -Age, size and temperament of the horse -Fracture location and configuration -Compound fractures -Money

Issues to consider with conservative treatment of fractures

-All fractures want to heal -All fractures should eventually heal (in theory) -Horse may fail before fracturehealing can occur -How long is it humane to continue treatment?

Removal can be difficult as access to the deeper portion of the fragment can be difficult and exposure is poor. Haemorrhage can be considerable. Despite these problems wound healing is usually satisfactory, although good closure is required and post op drainage allowed for. Even though the biceps brachii tendon is transected and the joint capsule and articular surface disrupted, these horses can be moderately useful. A racing career may be optimistic for all butthe smaller fractures but a reasonable level of athletic activity may be successfully achieved. There may be a long term cosmetic blemish (slight atrophy evident and a scar) and low grade residual lameness in some cases.

Fracture of the neck and body of the scapular are less common. The muscle covering of the scapular can result in some fractures healing with conservative therapy. Unfortunately the scapular does move considerably which can delay healing and result in a non-union. Some fractures in appropriately sized horses can be stabilised using bone plates. However the scapular is quite weak at this point so fixation should only be considered in selected cases (i.e. appropriate size and sufficient bone proximal and distal to enable good screw fixation).

Neck fractures are not very amenable to surgery due to insufficient distal bone for fixation. In selected cases sufficient stability may be provided by surrounding muscle to allow some form of healing. Complications would include post fracture swelling as well as complications relating to prolonged non-weight bearing on the leg.

Humerus (Mid body shaft)

The best thing to do for a horse with humeral fractures is to keep them away from a surgeon. There are various heroic descriptions of internal fixation where the horse miraculously survived. However horses with these fractures stand a better chance of survival if left alone. The humerus is not a good candidate for internal fixation given its shape, structure and location. In younger foals the bone is too weak to support screws while in older horses they are too heavy to support implants resulting in catastrophic breakdown in recovery.The exposure is poor so there is a high incidence of post-op infection.

Left alone all humeral fractures want to heal, even if they appear severely displaced. Younger horses will heal quite quickly. Affected horses can go on to lead an athletic career.

The main complications relate to pain control and non-weight bearing. Some horses will not tolerate the pain and require euthanasia however most will get used to the pain and cope quite well. The size and age of the horse are important factors with larger, older horses more likely to have slower healing and more complications. Once a horse starts to lie down for long periods it is a positive sign as the horse feels capable and confident of getting up and down. Prolonged recumbency should be encouraged. There is no simple means of controlling pain, with PBZ still being the most effective medication. Most horses will be non-weight bearing for about 6-8 weeks. This seems to be a reasonably consistent time period. After this time there is usually some improvement as the fracture has stabilised. Often within weeks after this the horse will be taking full weight on the leg. If the horse and owner can get through the initial 6-8 week period the long term prognosis is reasonable.

Many owners get frustrated at the apparent lack of progress in the initial 6-8 week period. It is important to reassure them not to expect anything for this time followed by a relatively rapid improvement if appropriate healing is taking place.

Complications relate to a long period of nonweight bearing. In the affected leg contracted tendons can develop, particularly in young horses. There is no way of preventing this but hopefully the problem will improve once weight bearing commences. Surgery may be required in severe cases of tendon contraction.

In the opposing leg laminitis is a constant risk, the development of which usually has a fatal outcome. The other problem, primarily in younger horses, is the development of ligament laxity or stretching, particularly about the carpus, which results in hyperextension. This can also be severe enough to be life threatening. Support bandages may help in the short term, but the problem can only be resolved effectively once weight bearing occurs in the fractured leg. Slinging of horses can reduce the weight placed onthe limbs and in theory should reduce the risk of contralateral laminitis. They do require constant supervision and intensive management as well as appropriate harnesses and support structures. Unfortunately there are insufficient good studies demonstrating the benefits of slinging enhancing the success rate of equine fracture repair.

Humerus - proximal growth plate

These are not uncommon in young horses. Horses present with severe lameness which can be difficult to localise. Initial radiographs may appear unremarkable but careful evaluation may reveal slight mal-alignment of the humeral head.

After several weeks sclerosis and new bone formation will be clearly evident radiographically. Providing there is not too much displacement, which is usually the case, the prognosis can be quite good.

These often do not become completely displaced. This fracture will heal. Good weight bearing will take approximately 6 weeks from the time of injury. Up until that point the horse will be non-weight bearing lame. One of the biggest complications of these fractures, particularly in young horses, is tendon contraction in the affected leg and collapse of the weight bearing leg. Once stability is achieved affected horses usually make rapid progress.

Supraglenoid tubercle fractures of the scapula are usually best treated by removal rather than internal fixation.

The best thing to do for a horse with humeral fractures is to keep them away from a surgeon. Left alone all humeral fractures want to heal providing the good leg holds together and the pain can be managed

Displaced supraglenoid tubercle fracture. Internal fixation is very challenging and usually unrewarding

Access is limited due to the extensive soft tissue covering

Large fragments can be removed resulting in freedom from lameness Slinging a horse with a humeral fracture. These cases require excellent nursing care and pain management

Humeral - stress fractures

These can be an intermittent cause of severe lameness and can be difficult to localise. Any horse with recurrent severe lameness after exercise that resolves quite quickly and that cannot be localised to other sites should be suspected of having a stress fracture, often being the humerus. They can progress to full fracture with continued work. There is data to suggest that most if not all catastrophic humeral shaft fractures occur secondarily to pre-existing stress fractures.

Accurate diagnosis is best achieved by scintigraphy but can also be detected by radiographs once sclerosis and new bone formation occur. Prognosis is good if the fracture has a chance to heal.

Olecranon fractures

Most olecranon fractures benefit from internal fixation, even those that are not intra-articular. If good stabilisation can be achieved there is rapid healing of the fracture and early return to full weight bearing (within days of surgery). However the incidence of complications following olecranon surgery is grossly underestimated and under-described in every equine text. When they go well they go very well, when they go badly they are usually a disaster. There is a multitude ofdifferent combinations and permutations in regard to olecranon fractures so that each case must be assessed individually.

Radius

Fractures of the radius can be a major problem. Proximal radial growth plate fractures are best stabilised by plate fixation down the caudal aspect of the radius and ulna. It is usually possible to get one screw in the epiphyses, several screws in the proximal portion of the olecranon then 6-8 in the radius. Alignment of the fracture can at times be difficult but usually sufficient apposition can be achieved to result in good stability and subsequent fracture healing. If very good alignment is achieved then good long term athletic activity can be expected.

Displaced mid-body radius fractures have a very poor prognosis. Unless the horse is small (less than 250-350 kg) repair is usually not successful. Conservative treatment is usually not successful due to the lack of soft tissue or muscular support and the inability to provide external support, such as a cast. Double plate fixation can be successful in smaller or younger horses but has a very high complication rate, in particular catastrophic breakdown on recovery and longer term infection even if the horse does stand up successfully.

Classic dropped elbow in an olecranon fracture. These should not be confused with radial nerve paralysis There is often severe soft tissue trauma associated with olecranon fractures

Many olecranon fractures are compound. Despite this good healing can be achieved due to the stability that internal fixation can provide

Intra-articular olecranon fracture

Tension band plating on the caudal aspect of the olecranon provides good mechanical supportand stability

Olecranon fractures should be repaired as soon as possible as flexor contracturecan rapidly develop and greatly compromise the outcome, particularly in younger horses Displaced mid-body radius fractures have a very poor prognosis and except in lighter horses and foals are not generally consideredcandidates for surgical repair

Radius fracture in a 9 mth old TB

It is a race between implant failure and fracturerepair in this case. The use of locking plates today has decreased the risk of screw loosening as is occurring here

Acommon fracture of the radius, which results in severe lameness, are non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures. These may not immediately be clearly apparent radiographically and are often accompanied by an open wound or evidence of direct trauma. Once these fractures are identified radiographically they can look very dramatic, often with multiple fracture lines that appear to be many millimetres apart. These horses may initially be non-weight bearing lame. However if the fracture pieces are even vaguely in the same area and there is no obvious gross instability of the limb, then conservative treatment is indicated. Such fractures will heal quite quickly and the horse will resume limited weight bearing more quickly than might be expected.

Some of these horses may also have concurrent wounds or sequestration. These need to be managed under local anaesthesia if needed. Otherwise they should be treated conservatively until fracture repair has been sufficient to allow aGA.This may be 3-4 months following injury. The outcome for such fractures, despite their often dramatic appearance both clinically and radiographically, can be very good.

Despite suspecting a radial stress fracture it was four weeks before it could be clearly seen

At follow up at 3 mths the extensive callous more proximal in the radius indicated the fracture was more complex than could be originally diagnosed. The horse made a full recovery Minimally displaced radius fracture extending into the carpal joint. The horse was grade 2/5 lame. Clearly the fracturehas been present for at least 4-6 weeks before diagnosis

There had been considerable purulent discharge from a wound associated with this fracture. The radiographic and clinical findings werehighly suggestive of a sequestrum forming. This can only be treated once the fracture has resolved unless it is removed standing-which is not encouraged These Salter-Harris type fractures can have agood prognosis if treated conservatively

Foal lame for at least 4-6 weeks. Referred for lameness evaluation. Tendon contracture in the affected leg is the biggest issue, moreso than contralateral laminitis, in this case

Healing Salter-Harris proximal radius fracture. These often heal well due to excellent blood supply to growth plate and the cell types present at this location. This case could be successfully treated conservatively due to the age and size of the horse, fractureconfiguration (minimally displaced and sufficient stability)

The filly made a full recovery from the fracture but.. Displaced and unstable distal radius fracture in a yearling Arab

Femoral fracture

Proximal and mid-shaft femoral fractures are not meant to be surgical cases. As with humoral fractures most will heal if the horse can survive long enough. The muscle mass about the femur can be sufficient to stabilise the fracture. This fracture can be extremely painful and many horses will not be able to cope. Severe anxiety, sweating, not eating, non-weight bearing and an inability or reluctance to move at all are indications that euthanasia is required.

If the horse tolerates the pain, then healing can begin to occur in 6-8 weeks, depending on the age and size of the horse. Again, little progress will be made in the first 6 to 8 weeks followed by more rapid progress. Older horses may take longer.Complications of such fractures are severe haematoma formation, the haemorrhage involved sometimes can be so severe as to be fatal. Laminitis in the opposing leg is a continual problem.

Distal femoral fractures, particularly involving the growth plate are usually poor candidates for treatment. They are usually too unstable making the horse very distressed. Reduction of displaced growth plate fractures is extremely difficult, if not impossible. The overriding caused by muscle tension usually cannot be overcome to allow adequate reduction. These are verypoor to hopeless candidates, irrespective of what treatment is used.

Femoral head dislocation

Although not a fracture, dislocation of the femoral head can present as an acute onset of severe lameness that may be confused with a fracture of the femur. There are several differences in the clinical appearance. Firstly fractures of the femur are usually excruciatingly painful, far more so than a dislocated femoral head. Adislocation also improves quite quickly and can present as a chronic lameness. Secondly many horses with a dislocation will bear some weight initially and again this can rapidly improve. Characteristically they will stand with the toe of the affected leg turned out quite noticeably. Conservative therapy carries a poor prognosis while successful surgical reduction and stabilisation has proved elusive in horses. The best option is a femoral head resection, which is relatively straight forward to perform. The best results are in smaller horses and ponies although I have not yet attempted the procedure in a horse above 400kg.

Proximal and mid-shaft fractures are not meant to be surgical cases. Most will heal if the horse can survive long enough, although pain and haemorrhage can be a real problem

Treated with carpal arthrodesis

Very turned out right hind leg

Radiographs can be obtained standing, even in larger horses

Despite the muscle covering good visualisation of the femoral head can be obtained. A single firm blow with an osteotome and heavy hammer is usually sufficient to shear the femoral neck Tibial fractures Tibial Stress fractures

These are known to have a higher incidence in young racing horses, particularly TBs. The history can often be one of intermittent lameness, often being very severe for a short time after fast exercise but making a rapid improvement to the point of not being obviously lame. Many of these horses continue in training despite these fractures, which is why by the time a diagnosis is made and radiographs taken there is often evidence of chronic new bone formation. It is also possible for the horse to suffer from complete breakdown of the tibia either during fast exercise oreven recovering from anaesthesia.

The best treatment is rest with return to exercise once the repair process has been completed. This can take 3-6 mths.

Displaced Tibial Fractures

Displaced tibial fractures are possibly the worst fractures to have in a horse. They are grossly unstable are there are virtually no successful treatment options. Biomechanically it is a very poor candidate for plating except in the smaller horse. If the fracture is very distal, internal fixation or trans-fixation pins may provide some hope. The prognosis is pretty guarded to absolutely hopeless.

Non displaced distal tibia fractures can heal with conservative therapy

Severefractureof the distal tibia. Surgical repair is extremely difficult if not impossible and invariably unrewarding

Displaced tibial fractures are possibly the worst fractures to have in a horse. They are grossly unstable are there are virtually no successful treatment options

Yearling with fracture of proximal tibial growth plate

Radiograph of horse above

Fracturerepair using a T plate. T plates are generally too thin for routine equine use and need to be supported by additional plates Fractured tibia. This occurred during recovery from anaesthesia

This is the tibia at left dissected out. These are poor candidates for surgical repair (particularly now)

Tibial crest fractures

Care must be taken not to confuse the normal appearance of the proximal cranial tibia with afracture. Many tibial crest fractures are not intra-articular or are minimally displaced so that conservative treatment can be effective. Displaced fractures, particularly with an intraarticular component, can be treated surgically with tension band plating.

Wound just distal to top of tibia

Following preparation for surgery

Radiographs indicate a displaced fracture of the tibial crest

Note extent of displacement, the forceps are holding the end of the fragment

Does the term ‘Dietary Elimination Trial’ send chills up your spine?

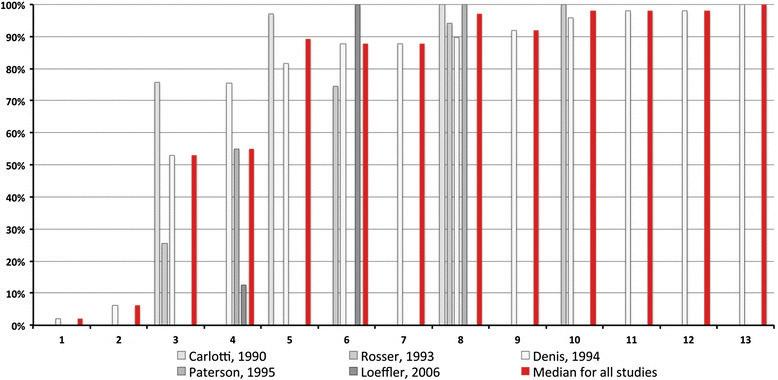

Dietary elimination trials (DET) are commonly discussed in clinical environments with our client base as best practice1 to diagnose Cutaneous Adverse Food Reactions (CAFRs)2 or Food-Induced Atopic Dermatitis (FIAD)3 in dogs and cats. However, have you considered DETs are a diagnostic test that we rely completely on the client to perform and interpret the results allowing us to determine a diagnosis? Additionally,this is one of the longest diagnostic assessments for a condition, typically spanning eight totwelve weeks, in order to accurately diagnose 90 per cent of cases (Figure 1 & 2)2.Combine these two factors, and it is no wonder that many of us have an overwhelming feeling of anxiety when we see an itchy patient in our appointment schedule for the day.

With all of that in mind we can clearly see why the main reason for failings in a DET either in general practice or referral would boil down to client compliance. So how do we set them up for success in managing this complex process in order to be the best patient advocates that we can be as veterinarians? The reality is that it isn’t captured within a fifteen-minute consultation period and will require a team effort from the practice with plenty of follow up and communication. Two-way communication and collaboration is essential in obtaining the most valid data set for interpretation which will lead to a final diagnosis (Figure 3).

Figure3.Recommended Key Communication Points for Dietary Elimination Trial Patients

• Pre-appointment comprehensive dietary and clinical history questionnaire • 1-week check to ensure transition of diet went well • Reminder this is when the feeding trial commences • 3-weeks to check on compliance and answer any questions • 5-weeks re-check appointment to assess if any additional management interventions are required • 7-weeks to continue compliance and answer any questions and book re-check • 9-weeks re-check appointment to consider results and start challenge • 10-weeks to check in and ensure no clinical signs have appeared with the challenge diet • 11-weeks recheck appointment to consider results and settle on a diagnosis of food related disease or not, and longtermmanagement options

Figure 1. Cumulative percentages of clinical remission in 209 dogs with CAFRs over time (in weeks)2

SOURCE FILE: Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (1): duration of elimination diets| BMC Veterinary Research | Full Text (biomedcentral.com)

Figure 2. Cumulative percentages of clinical remission in 40 cats with CAFRs over time (in weeks)2

SOURCE FILE: Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (1): duration of elimination diets | BMC Veterinary Research | Full Text (biomedcentral.com)

Taking one step back, what is required for a DET? The most important piece of information, again relying on the pet owner, is afull and detailed historyof all proteins that the pet has likely been exposed to. This can be by means of primary diet (i.e., commercial pet foods), as well as treats (including table-scraps), medications and supplements to build a complete data base of the different meat and carbohydrate-based proteins that the patient has consumed throughout its life. This is complicated for pets feeding commercial diets as most commercial pet foods will contain a mix of protein sources leading to multiple exposures within a single diet4 .

Ideally to manage a DET,adiet would be formulated for that individual patient avoiding all these protein sources, and therefore identifying a ‘novel’ protein diet5 for that patient. This is where the concept of ‘home-cooked’ diets was founded for DETs. By individualising the elimination diet to that patient, we achieve the best chance to determine the trigger for that individual. The other approach is to use hydrolysed proteins, ideally less than 10kDa in size2 . These can be novel or ones that the patient might have previously been exposed to in order to reduce the chance of an allergenic response to those proteins. Hydrolysed diets have been produced by commercial pet food operators for many years using commonly known allergic proteins like chicken or beef6,or more uncommon sources of allergens like soy. More recent innovations, and gold standard, with extensively hydrolysed proteins using even more unique sources like feather protein hydrolysate (Royal Canin ANALLERGENIC) where 95 per cent of the protein composition for the diet is <1kDa in size, and 88 per cent is free amino acids, further reducing risk of immunologic reactions to the trial diet.

How do we then convey what is best for our patients to the pet owners? As a reminder, the outcomes rely completely on client compliance. Therefore placing ourselves in their shoes is important for the overall result for that patient. The absolute best practice for the patient from the diagnostic standpoint would be an individualised, complete and balanced novel protein home-made diet. The reality is, however,that this is more complicated than it sounds. A 2013 study demonstrated that home-made diets for maintenance (not with an added complexity of novel proteins and ingredients) were more often than not ‘unbalanced’ or ‘incomplete’ by AAFCO and NRC guidelines. Of the 200 recipes evaluated, 95 per cent had at least one nutrient not meeting the appropriate guidelines, and 85 per cent with 2or more7.Of the 5 per cent that were appropriately complete and balanced, these were all formulated by veterinary nutritionists, and the reason it is best practice to enlist their support when formulating a novel home-cooked diet for DET.

This all sounds great right? But how practical is it again for the pet owner who is at the centre for success with this diagnostic test?

There are limited veterinary nutrition referral sources around the globe, and even more so within the Asia-Pacific region. Majority of these services are based at Veterinary Universities where boarded Veterinary Nutritionists are employed. The cost for a digital nutrition consult for a home-cooked elimination diet will range anywhere from $230AUD – $630AUD atcost (not including any potential mark-up for these services) to get one or two recipes. Home-made diets have proved problematic at times for palatability8,and commonly multiple additional recipes might be required at further costs averaging an additional $215AUD per recipe. This is just for obtaining the recipe itself.

The requirement then is to follow through with the formulation, purchase the ingredients and have owners commit to daily food preparation for the patient. Majority of the formulated diets will utilise the only nutritionist developed vitamin and mineral supplement for cats and dogs from a company called BallanceIT© out of the USA. This therefore requires importing these supplements for the recipes, as well as purchasing locally several additional sources of essential fatty acids and micronutrients. A recent formula that I assisted a clinic with obtaining required an outlay cost of $400AUD per month for ingredients, working out at $13.25AUD per day for the ingredients alone. These costs currently match previous evaluations in the UK finding on average it cost 3.60€ more per day for a home-cooked diet compared to an extensively hydrolysed elimination diet like ROYAL CANIN® Anallergenic9 (Figure 4).

Circling back to the purpose of a DET and the reliance on pet owners for a complete, consistent approach during the elimination phase, this begins to shed light on the pressures that we place on our clients. While this would be a gold standard approach, we need to ask is it practical? How likely are we to achieve a diagnostic data set at the end of this trial period? And is it sustainable for the pet owner?

There is an unspoken fear of using commercial DET products in the veterinarycommunity. Some are founded, however others have been extrapolated from human medicine without an evidence based assessment. For example, there is ademonstrated connection in human medicine in which food additives have been attributed to food reactions, however this hasn’t been established as a definitive link in cats and dogs10 . Amore appropriate concern we should consider is how do we confirm that what is prescribed for your patients is exactly what it says it is? Some studies have found that up to 75 per cent of commercial diets, primarily non-prescription diets, have found discrepancies between protein declaration on pack compared to protein analysis11 on those products. This indicates risk of cross contamination in these products, and a potential to lead to a false-positive reaction. This is reasonable when we consider the financial investment required to have dedicated processing lines, stringent cleaning and decontamination procedures as well as release criteria like a negative ancillary protein PCR test on every batch produced. These are the criteria needed to be met for the distribution for the ROYAL CANIN® Anallergenic diet with dedicated research ensuring the absence of cross-contaminating proteins12 . This presents another opportunity for discussion with your pet owners about the importance of acquiring a reliable source of food for the DET to prevent the risk of undeclared ingredients that could lead to a failed elimination trial.

Hopefully that hasn’t scared you off ever approaching the management of a DET in your practice but does highlight the importance of dedicating some time in supporting clients in the best outcome for their pets and your patients. The trade-off between best practice and achieving a diagnostic outcome for DET is a case-by-case assessment on the financial investment, as well as the workload and lifestyle of the pet owner to manage a complicated process. Prescription based commercial pet food designed for DET are a fantastic tool supporting your dermatology cases in practice. They are high value for money items that add additional securities to the diagnostic assessment and can facilitate a more positive relationship with the pet owner and their companion.

■ DR. COREY REGNERUS-KELL BVSc, BSc Royal Canin Australia & New Zealand Scientific Services Veterinarian

References

1. Mandigers, P.J., Biourge, V., van den Ingh, T. S., Ankringa, N., & German, A. J. (2010). A randomized, open-label, positively-controlled field trial of a hydrolyzed protein diet in dogs with chronic small bowel enteropathy. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine(24), 1350-1357. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0632.x 2. Biourge, V.C., Fontaine, J., & Vroom, M. W. (2004). Diagnosis of Adverse Reactions to Food in Dogs: Efficacy of a Soy-Isolate Hydrolyzate-Based Die. The Journal of Nutrition, 134(8), 2062S-2063S. doi:https://doi.org/10. 1093/jn/134.8.2062S 3. Cadiergues, M. C., Muller,A., Bensignor,E., Heripret, D., Yaguiyan-Colliard, L., & Mougeot, I. (2015). Cost evaluation of home-cooked and an extensively hydrolyzed diets during an elimination trial: a randomized prospective study. Veterinary Dermatology(32), 302. 4. Guilford, W. G. (1996). Adverse reactions to food. In W.G. Guilford, S. A. Center,D. R. Strombeck, D. A. Williams, & D. J. Meyer, Strombeck’s Small Animal Gsatroenterology (pp. 436450). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders. 5.Horvath-Ungerboeck, C., Widmann, K., & Handl, S. (2017). Detection of DNA from undeclared animal species in commercial elimination diets for dogs using PCR. Veterinary Dermatology,28(86), 373. 6. Lesponne, I., Naar, J., Planchon, S., Serchi, T., &Montano, M. (2018). DNA and protein analysis to confirm absence of cross-contamination and support the clinical relaibility of extensively hydrolysed diets for adverse food reaction-pets. Journal of Veterinary Science, 5(3), 63. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.3390%2Fvetsci5030063 7. Mueller,R. S., Olivry, T., & Prelaud, P. (2016). Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (2): common food allergen sources in dogs and cats. BMC Veterinary Research, 12(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s 12917-016-0633-8 8. Olivry, T., Mueller, R. S., & Prelaud, P. (2015). Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (1): duration of elimination diets. BMC VeterinaryResearch(11), 225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-0150541-3 9. Rosser,E. J. (2013). Diagnostic work-up of food hypersensitivity. In C. Noli, A. Foster, & W. Rosenkrantz, Veterinary Allergy (pp. 119-123). Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons. 10. Stockman, J., Fascetti, A., Kass, P. H., & Larsen, J. A. (2013). Evaluation of recipes of home-prepared maintenance diets for dogs. Jounal of American Veterinary Medical Association, 242(11), 1500-1505. doi:10.2460/javma.242.11. 1500 11. Tapp, T., Griffin, C., Rosenkrantz, W., Muse, R., & Boord, m. (2002). Comparison of a commercial limited-antigen diet versus homeprepared diets in the diagnosis of canine adverse food reaction. Veterinary Therapeutics, 3(3), 244-251. 12. Verlinden, A., Hesta, M., Millet, S., & Janssens, G. P.(2006). Food Allergy in Dogs and Cats: A Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 46(3), 259-273. doi:10.1080/ 10408390591001117

Footnotes

1(Verlinden, Hesta, Millet, & Janssens, 2006) 2(Olivry,Mueller,&Prelaud, 2015) 3(Rosser, 2013) 4(Mandigers, Biourge, van den Ingh,

Ankringa, & German, 2010) 5(Biourge, Fontaine, & Vroom, 2004) 6(Mueller, Olivry, & Prelaud, 2016) 7(Stockman, Fascetti, Kass, & Larsen, 2013) 8(Tapp, Griffin, Rosenkrantz, Muse, & Boord, 2002) 9(Cadiergues, et al., 2015) 10 (Guilford, 1996) 11 (Horvath-Ungerboeck, Widmann, & Handl, 2017) 12 (Lesponne, Naar, Planchon, Serchi, &Montano, 2018)