4 minute read

Forgotten Facts

from 10012021 WEEKEND

by tribune242

The economics of the Bahamas

Virgil Henry Storr, PhD, is a Bahamian member of the faculty of the George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia and the author of “Enterprising Slaves and Master Pirates”, a book about the economic life of the Bahamas.

Advertisement

Published in 2004, to offer “an interdisciplinary account of life in the Bahamas”, Storr tells us that the economic culture of the Bahamas is dominated by two types of entrepreneurs, hence the title of his book.

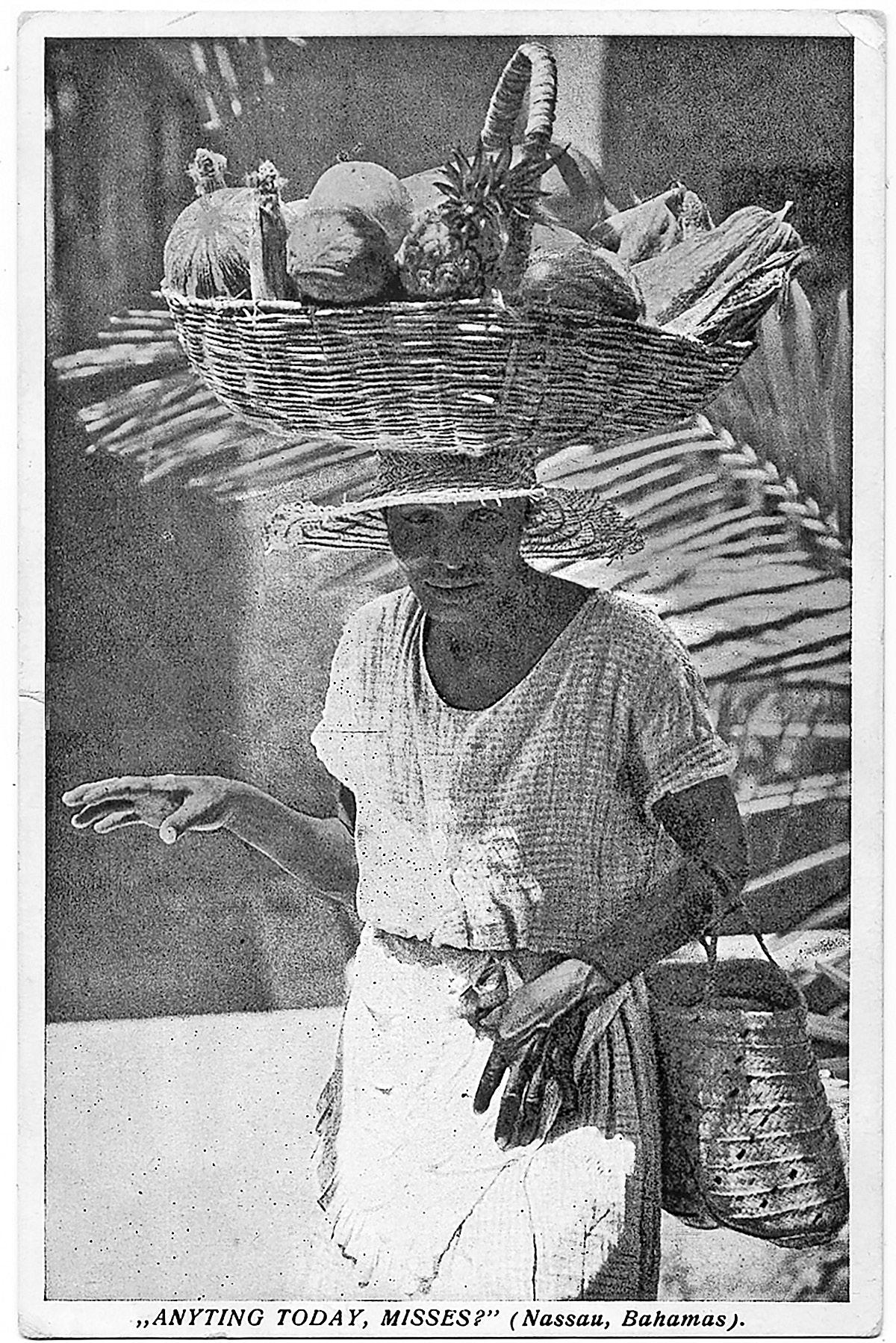

The enterprising slave is a product of the Loyalist period of Bahamian history, when it was not uncommon for slaves to be allowed the weekend off to operate their own small businesses. For the slaveowners, this offered some relief from the constant problem of how to feed their slaves. The owners assigned plots of land (usually, less arable plots) for slaves to grow their own food and free time to work these plots and sell some of the crops, thus allowing slaves to produce much of what they ate – including bananas, coconuts, plantains, yams and other vegetables – and improved the quality of their lives. Their gardens became a fundamental part of slave life and created thriving markets for their produce.

In my childhood, long after slavery had been abolished, Nassau residents bought from enterprising descendants of slaves, who balanced their wares on their heads and walked the streets peddling their wares. A few of them called at our home every morning on their way to the Public Market. Some walked from Adelaide (and back) to sell bletia orchids (Bahamian bletias were the first orchids in Kew Gardens in England). Each of them was perfectly capable to price things correctly in pounds, shillings and pence (without iPhones and computers) and these entrepreneurs knew how much to collect and exactly how much change had to be given.

Storr makes us understand that slaves (and exslaves) “view the higgler traditions as more than a means of subsistence, but as an opportunity to attain real economic success.”

Piracy goes further back in Bahamian history and flourished until 1718, when Woodes Rogers sailed into the harbour. As the islands’ new governor, he came with sufficient military power to put down the long-established ‘pirate republic’, offer amnesty to repentant pirates (of which there were many) and hang the few that would not co-operate.

Once the pirates had been expelled and commerce restored, the Colony eventually chose the new motto ‘Expulsis piratis restituta commercia’ (pirates expelled, commerce restored).

Its new emblem showed a British man-o-war chasing two pirate ships away from the waters of the colony. It is not difficult to imagine Woodes Rogers at the tiller of that man-o-war.

Piracy, as such, may have been expelled, but when doing business in the Bahamas, one might be excused for thinking that piracy – albeit under a variety of respectablesounding names – is still alive and flourishing today. “Extra-legal matters are not simply accepted in the Bahamas, they are encouraged by, and celebrated in Bahamian culture and, at various times, have sustained the economy,” Storr writes.

Comparing differences in culture, Storr describes an American woman who walks to work, wearing gym shoes, and changing into business shoes once she reaches the office. This message sent is: “I am here now, and I have come to give a full day’s work, for a full day’s pay.”

On our side of the Gulf Stream, the Bahamian counterpart drives to work “fully-adorned in business attire” - her shoes, her briefcase and her business suit suggest that she is a serious worker - but once she gets to work, she undergoes a metamorphosis, removing her expensive business shoes and putting on a pair of bedroom slippers that she bought for wearing around the office. “I am here to get a full day’s pay, for doing as little work as possible.”

Of customer service, Storr states bluntly: “Customer service in the Bahamas is indeed poor.”

I wish I could argue with this, but I have been waiting for over a month for my BTC landline phone to be ported over to a competitor. Most frustrating is the fact that it is virtually impossible to phone that competitor and actually talk with a human being. Even if I know my party’s extension number, it seems impossible to connect with a human. Through perseverance (and a lot of good luck), my wife and I have managed to talk with a few living voices, each of whom has promised that our landline will be connected to our newly rentedhouse, each of whom has let us down.

On page 122, Storr writes (and quotes Patricia Glinton-Meicholas) that the truth of success depends on ‘who you know’ – if you ever voice a difficulty that you seem unable to solve, the average Bahamian will ask, “Don’t you know somebody?”