6 minute read

Art 8-9

from 08062021 WEEKEND

by tribune242

art Challenging traditional standards

In response to a new two-person exhibition entitled ‘Life’s Balance’ now open at The Brighton Storeroom, in St George, Barbados, the well-known Bahamian artist JOHN COX writes about his and his fellow exhibiting artist Tessa Whitehead’s practices.

Advertisement

YEARS ago, I recall a conversation I had with a faculty member at the University of the Bahamas. He was an Anglican priest as well as a professor in the School of Social Science. He explained to me the reason the parishioners processed counter-clockwise while preparing for communion was to pay tribute to the ancestors. This simple yet deliberate gesture during the mass had a specific meaning that no one would ever know without asking or being told.

It’s these little moments within traditional customs that reveal so much.

I was never good at school or anything that people who were taken seriously were good at. I always needed alternative ways to see and process information and ideas. I remember being terrified in high school that I would fail every test I took and subsequently be labelled lazy or not intelligent. I took US history and was mortified by the volume of content I needed to digest. Not being strong reader, I countered by listening very attentively to discussions in class and took more notes than anyone. So much so that my instructor ended up grading my notebooks instead of my exams. He mentioned that I had paid more attention to his lectures than most and that had to count for something.

Thirty years later I see myself relating to my environment not unlike how I remember relating to that US history class. At times overwhelmed and intimidated by the complexity of what is going on around me I still navigate things by paying close attention, listening and taking notes. I feel like both Tessa (Whitehead) and I in many respects see value in keen observation of our surroundings. Our practices overlap in the sense we both produce work as a form of note taking - a kind of exploring and reflecting at the same time.

The art world is filled with so many standards of tradition, perfection and excellence. So much so we can find ourselves erased from the notion ‘perfection’ where the ‘ideal’ replaces the personality. How we know we were here is marked by how we respond to these standards and expectations. It is our flaws that define us, free us and ultimately save us.

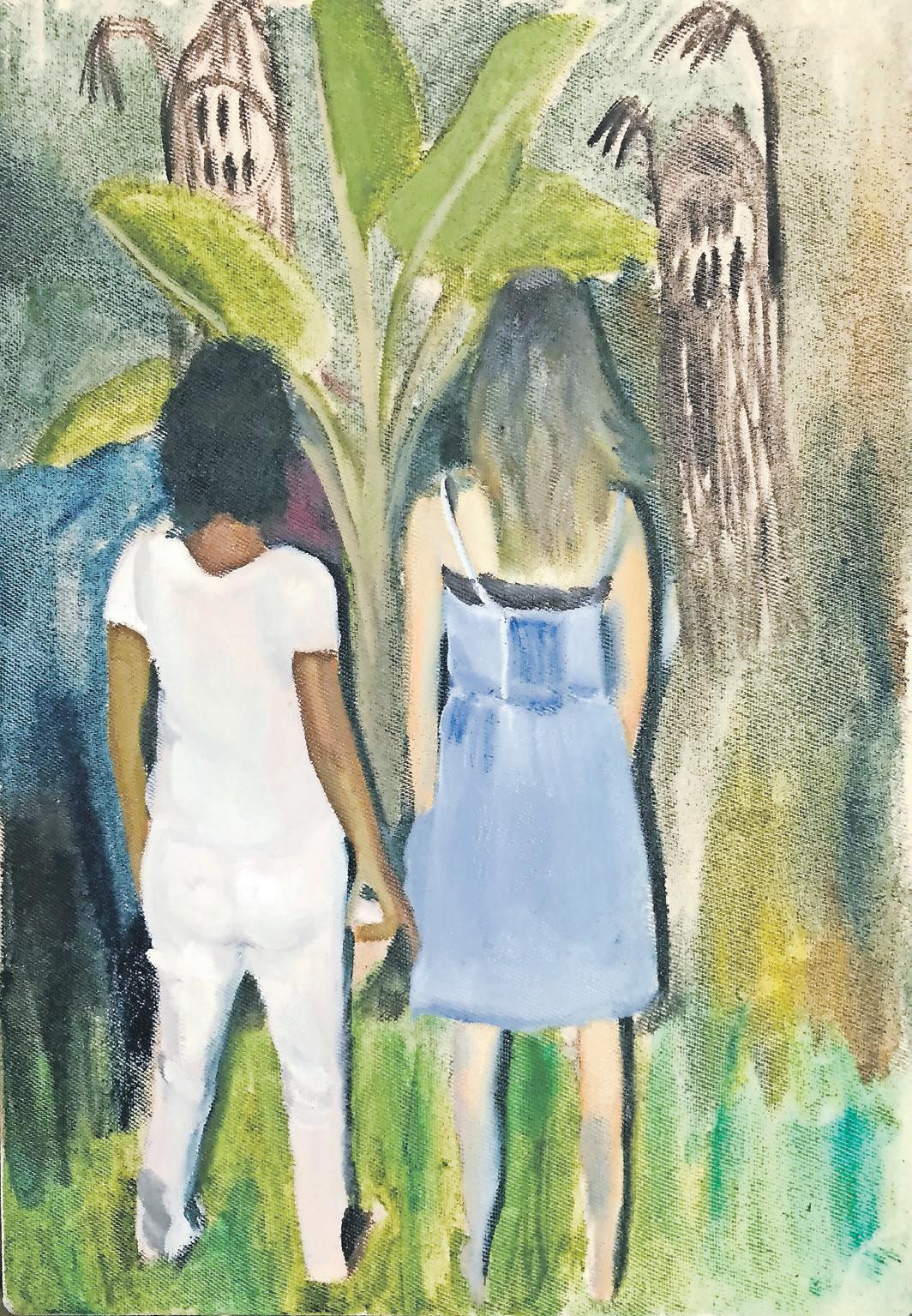

Tessa’s exploration of her history, environments and tendencies is one that both abandons the ideas of perfection while simultaneously achieving it. Her work, like few others in the region, screams of raw experience, colour, texture, tension, stories and commentary while paying little attention - at least on the surface - to any of these things. Her mastery of composition and intuitive gestures suggest a playfulness on top but possess a much deeper commentary on Caribbean life and where she fits and contributes into it significantly lingers in her work. Her work invites/encourages you to take notes on what otherwise would be overwhelming complex.

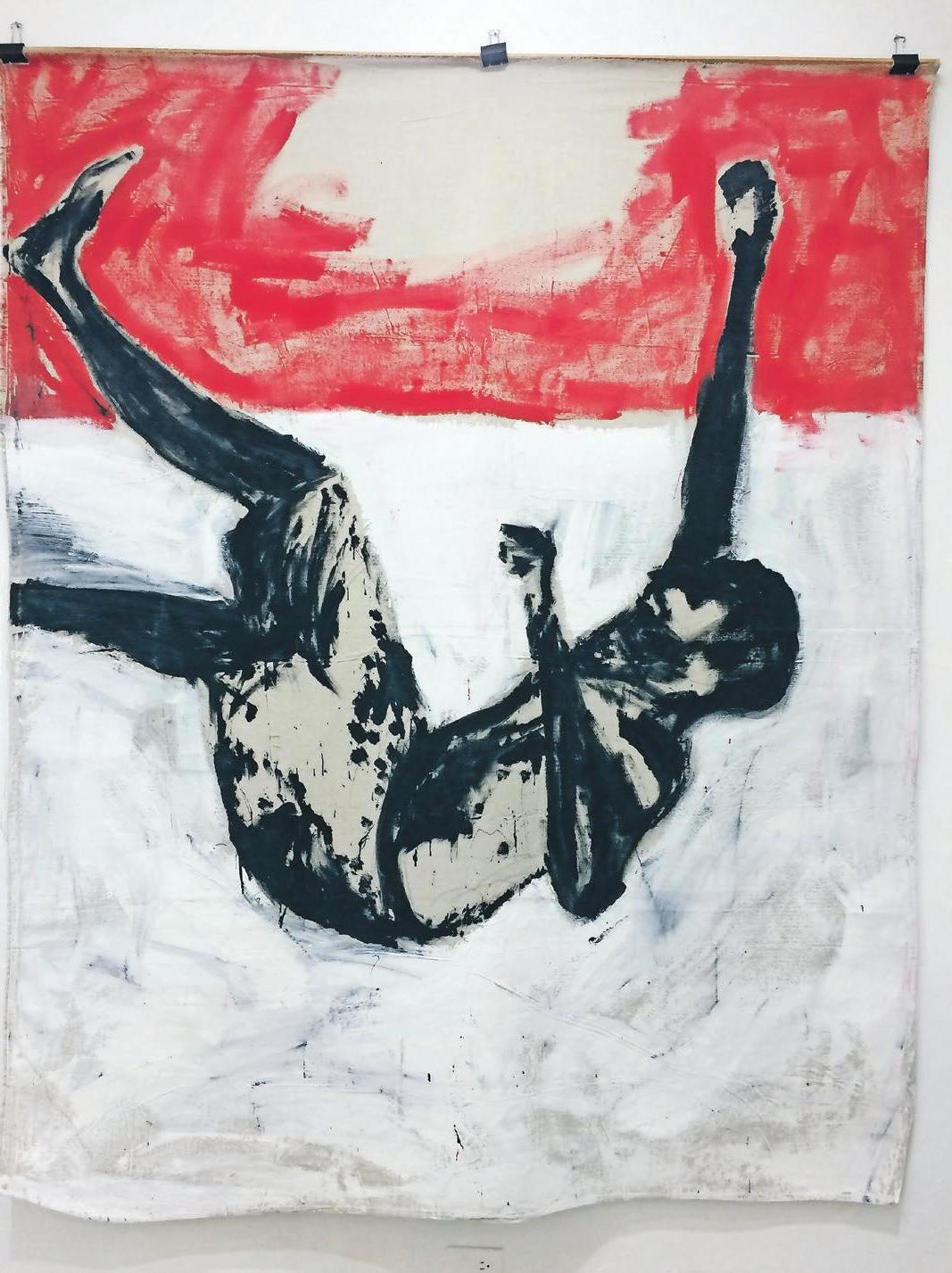

My work looks at history through the lens of this environment in broad and simple terms. I never feel validated by curators or academics, but do think for some, the contributions I’ve made offer a window into an honest human experience. An experience that might allow for one to insert oneself into the make-believe narratives of balance, service and perseverance that my work investigates. Like Tessa, I think we both place value on memory and our own unique experiences to find traction and context within a broader cultural conversation.

Narratives and symbols are borrowed from knowledge both observed and told to us.

It is our flaws and imperfections that enable us to find meaning in our own histories and experiences. Like the meaning in the counter-clockwise procession in the Anglican mass so do we find religion in falling figures and leafy bushes. FALLING Figure/ from the fight series (2015) by John Cox

The boy who took flight but never quite grew up

Sir Christopher Ondaatje

writes about the life of the Scottish novelist and playwright who is best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. He also wrote a number of successful novels and plays.

“The Life of every man is a diary in which he means to write one story, and writes another; and his humblest hour is when he compares the volume as it is with what he vowed to make it.”

- J M Barrie

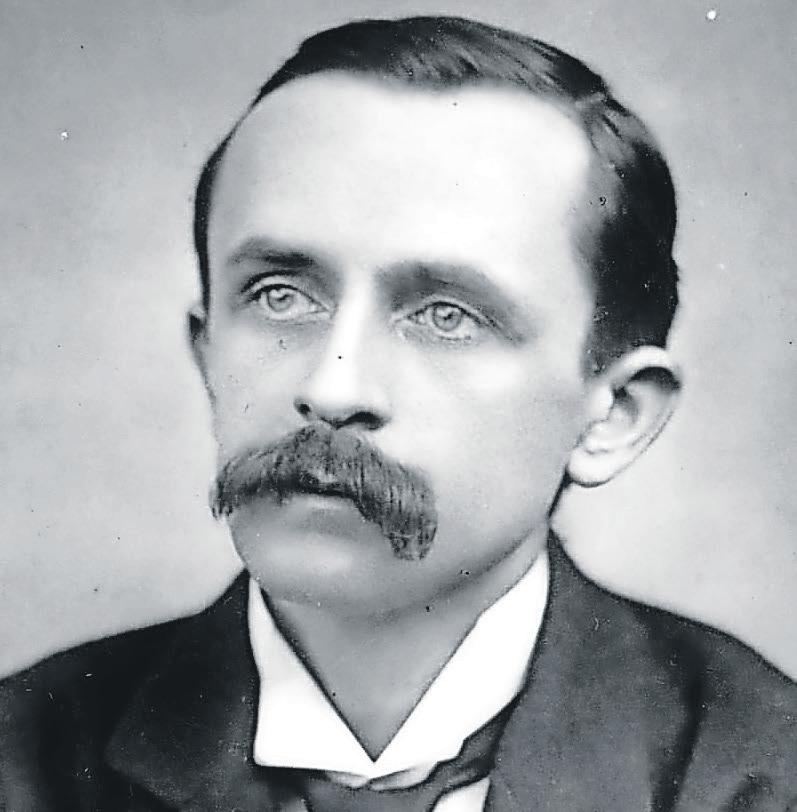

James Matthew Barrie was born in Kirriemuir, Scotland, on May 9, 1860. His father, David Barrie, was a successful weaver. His mother was a devout Presbyterian. Barrie was the ninth child of ten (two of whom died before he was born). He was a small child and drew attention to himself with storytelling. He grew to only 5 feet 3½ inches. When he was six years old he was shocked by the horrific death of his older brother David in an ice-skating accident – a day before his fourteenth birthday (He was hit by a fellow ice-skater, fell, and cracked his skull).

Barrie tried to fill David’s place in his devastated mother’s attentions – even wearing his clothes and whistling in the same way.

Barrie and his mother entertained each other with stories of her childhood and books like Robinson Crusoe and The Pilgrim’s Progress. Many years later he composed an intimate portrait of her in his bionovel Margaret Ogilvy (1896), published a year after she died. He never forgot his childhood and perhaps never grew up.

When he was eight years old, he was sent to Glasgow Academy where his two eldest siblings, Alexander and Mary Ann, taught. Two years later he returned home and continued his education at the Forfar Academy. When he was fourteen, he left home again for Dumfries Academy – again watched carefully by his elder brother and sister. He was a clever pupil and became a voracious reader. At Dumfries he and his friends played a pirate game that eventually became the play Peter Pan. He produced a play, Bandelero the Bandit, which was denounced by a clergyman on the school’s board because of its immoral overtones. He went on to the University of Edinburgh, studying literature and writing reviews for the Edinburgh Evening Courant. He graduated on April 21, 1882, with an MA.

Determined to follow a career as an author, and with some advice from his elder sister, he worked for eighteen months as a journalist on the Nottingham Journal. When he got back to Kirriemuir, he sent a piece to the St James Gazette, a London newspaper, using his mother’s stories about the town where she grew up – renamed “Thrums”. The editor of the Gazette liked his Scottish reminiscences and he commissioned Barrie to write a series. They eventually served as the basis for his novel novels: Auld Licht Idylls (1888), A Window in Thrums (1889), My Lady Nicotine (1890), and The Little Minister (1891).

“Auld Lichts” was a strict religious sect to which his grandfather had once belonged. These early stories were popular enough among English readers to establish Barrie as a successful writer. He moved to London in 1885. He had previously published Better

JM Barrie and, right, an illustration by Gerald Scarfe of the author.