6 minute read

Who owns the water from Lake Tahoe & Truckee River? Part III

BY MARK M c LAUGHLIN

Throughout the 1870s, diversion dams and canals sourcing the Truckee and Carson rivers were built in western Nevada to provide domestic water for Reno and Carson City, irrigation for agriculture and ranching, as well as mining operations and hydroelectric power generation.

Advertisement

Before the Nevada Supreme Court formerly approved the Silver State’s adoption of the Doctrine of Prior Appropriation in 1885, state courts supported the riparian doctrine along Nevada’s streams, which more freely allowed the use of surface water. Under prior appropriation, however, these rights became more restrictive with proof of rst use required.

One ingenious operation that diverted a feeder stream from Lake Tahoe was completed in 1873 when water from Marlette Lake, located in the Carson Range portion of the Tahoe Basin, was piped and umed via gravity 21 miles east to Virginia City. At its outset, this engineering marvel delivered 2.2 million gallons of pure mountain water to Virginia City every 24 hours. Additional pipelines increased that volume over time and still supply Nevada communities today.

Irrigation advocate Robert Fulton was no fan of politicians, but he needed meaningful political muscle if he was to tap the Tahoe Sierra water supply. In a stroke of good fortune, on March 3, 1877, the U.S. Congress passed the Desert Land Act that o ered citizens up to 640 acres of federal desert land for irrigation purposes at $.10 an acre. With irrigation the value of the land would skyrocket to an estimated $40 per acre, thus its appeal to farmers and investors. is legislation was inspired by the 1875 Lassen County Desert Land Act, which had determined that the 160-acre limit permitted by the original 1862 Homestead Act was insuf cient for the economic development of arid desert country.

Fulton recognized a good opportunity when he saw one and together with well-heeled, Reno-based investors formed Washoe Land and Water Company. eir intent was to ditch Truckee River water north to Prosser Valley and Dog Valley and then east to Lemmon Valley in Nevada. e nancial, political and marketing obstacles were formidable, however, and without government support the project languished. Other entrepreneurs were also stymied in e orts to seize Lake Tahoe water. In 1887, the Nevada and Lake Tahoe Water and Manufacturing Company proposed to bore a 4-mile tunnel through the Carson Range to connect the lake with the Carson Valley. ( is same scheme would be pitched as late as the 1950s.) Rivalries among potential water users in Nevada prevented any e ective cooperation on this project, as well.

In 1888, Fulton’s springboard to success arrived with Francis G. Newlands, a San Francisco resident who moved to Reno with plans for a future run for election to Congress. He would serve in both the House and Senate where among his accomplishments he sponsored legislation for the United States’ controversial annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898.

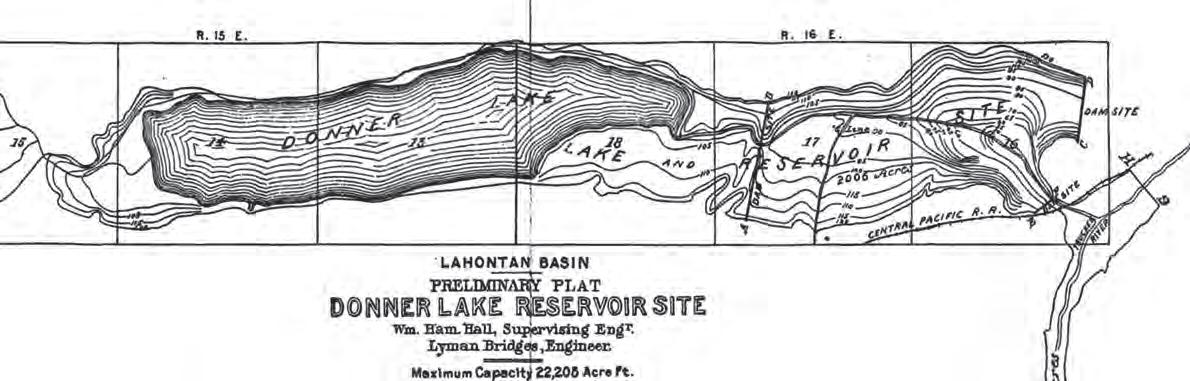

ABOVE: Proposed Donner Lake reservoir, circa 1888. | Courtesy Nevada Historical Society.

LEFT: Nevada Senator Francis G. Newlands. | Courtesy Nevada Historical Society

As a lawyer and son-in-law to former Nevada Sen. William Sharon, Newlands was a uent and well connected in both business and political circles. In 1889, Newlands began construction of a new house near the Truckee River on the blu s west of town, opposite and upriver of Fulton’s home. Like Fulton, Newlands supported a greater federal role in the funding of Western irrigation projects and proposed a network of reservoirs to serve the future development of Nevada. According to Newlands, Lake Tahoe a orded the “cheapest reservoir space in the West.” e goals and interests of Newlands and Fulton were strategically aligned and they soon became close allies. Now the pace quickened.

Newlands cultivated a friendship with the supervising civil engineer for the U.S. Geological Survey, William H. Hall. After he left the agency, Hall continued to con dentially inform Newlands on surveyed lands with irrigation potential. In January 1890, Hall reported his choices for the best storage sites: Lake Tahoe, Independence Lake, Donner Lake and Webber Lake within the Truckee River system and Long Valley and Hope Valley in the Carson River drainage. In response, Newlands spent $100,000 on sites near the Tahoe Dam, at Donner Lake where he had built a dam in 1889 and other promising locales mentioned by Hall. He purchased 300

In April 1890, Fulton nally persuaded property owners with riparian rights at Lake Tahoe to sign an historic agreement allowing Nevada to store water behind the dam for downstream farmers during the dry summer months. Many of these lakefront tracts were popular tourist resorts on the California side that relied on lower water levels for piers and beaches. West Shore resort owner John W. McKinney was the sole holdout who refused to sign the Lake Tahoe Agreement due to his concern that water would ood his property, especially since there was still so much snow in the mountains due to the preceding heavy winter. e Lake Tahoe Agreement basically absolved the Donner Boom company from any liability for damaged property in icted by the increase in water, a nancial commitment backed by Newlands’ control of a trust he managed for the uber wealthy, but now deceased, Sharon. e Tahoe Dam gates were shut that spring in 1890 and the water rose 6 feet, but no damage occurred.

A similar battle was being fought at Donner Lake, where Fulton was buying parcels of land that would be ooded when water behind Newlands’ new dam was impounded. Donner Lake property owners pushed back by refusing to sell or raising the price to buy. A new road would also need to be built above the high waterline. When Truckee residents got word of the plan to store water in Donner Lake for

acres along the Truckee River just north of the outlet, but control of the dam operations remained in the hands of Donner Boom and Driving Company. Nevada farmers, they protested with a petition to block the project. Local shermen, fearing the loss of spawning trout, threatened to blow up the dam.

In 1891, Fulton successfully lobbied the Nevada Legislature to pass an assembly bill that along with a Constitutional amendment permitted state money to be invested

Read the fi rst two parts & more about the Virginia City pipeline at TheTahoeWeekly.com

in district water bonds. By the following year, the Fulton-Newlands irrigation project had acquired nearly 40,000 acres of desert land that the men had decided to manage as a private corporation. Meanwhile, California politicians were agitating over these audacious plans to appropriate state water resources for use in Nevada.

President William McKinley had not supported large-scale, federally nanced irrigation projects in the West, but after his assassination in September 1901 Vice President eodore Roosevelt assumed command. Roosevelt signaled his approval for the idea and Congressman Newlands took advantage of the change in leadership to successfully push his agenda in the passage of the 1902 Reclamation Act.

Stay tuned for Part IV in the next edition or at eTahoeWeekly.com.