31 minute read

El Adele Oliveira

from TEXLANDIA 2022/23

Untouched Beauty By Daniela Pasqualini

El

Advertisement

Adele Oliveira

At first, when they didn’t hand her the baby, Cindy thought something was terribly wrong. Then she heard a cry, and Dr. Boyd made a sound too. He laughed. He ruffled his lips with an exhale, like a horse.

They brought Cindy the girl, swathed in receiving blankets. A nurse put her in Cindy’s arms and Dr. Boyd folded back a corner of the flannel, revealing the baby’s hip. By then, she was squalling.

“If you’ll look just here,” the doctor said, pointing to a large, port-wine colored stain that bloomed on the infant’s tummy and wrapped around to her back. Cindy squinted. The edges of the birthmark were clean and sharp, not irregular and meandering the way body markings usually are. The mark wasn’t solid, either. It had negative spaces within its shape, mimicking the deliberate artistry of a tattoo. The likeness was unmistakable. There was the swoop of the pompadour, the curl of the lip. The birthmark was the face of Elvis.

“I don’t understand,” Cindy said. “Why did this happen?”

“It’s a mystery!” Dr. Boyd sounded more delighted than alarmed. “I don’t think it’s anything to worry about, but we’ll zap it with bilirubin all the same. Nurse?”

December 2002, the week between Christmas and New Year’s. The day before, Cindy was enormous, losing track of the days. When her contractions had started in the afternoon, snow was falling heavily, already settling in drifts that nudged out into the streets. Debbie, Cindy’s mother and roommate, had driven in her RAV4, racing through the snow, the flakes coming at them in the headlights like stars at warp speed, while Cindy had whispered, “carefulcarefulcareful.” Debbie had stayed in the waiting room, because, “I think it’s better if I stay out here, don’t you?” None of the nurses thought to go out to tell her that her granddaughter had arrived, and Cindy did not remind them.

Satisfied with his work, Dr. Boyd strode away smiling and three nurses fell on Cindy, tugging at the plastic sheets beneath her, pulling back the sweat-soaked hospital gown to expose her breast. “That’s it dear. We call that a C-clamp.” Cindy registered the baby latching, the wailing ceasing, but she didn’t feel it. Exhausted, she collapsed against the bed.

Hours later she woke to stillness, save for the hushed whir of medical equipment, and went to examine the baby, sleeping in a neat plastic box they called a bassinet. When Cindy pulled back the blankets, her daughter stirred and kicked, but she did not cry. The baby’s face squished into wrinkles before smoothing again in slumber. The birthmark smirked up at Cindy. She smoothed her fingers across its surface, almost expecting it to smear, the joke finally revealed. But the birthmark was colorfast, indistinguishable in texture and temperature from her baby’s skin. Cindy wondered if it would stretch and fade. What did it mean, to be born with The King’s face emblazoned on your body? Cindy wasn’t sure how the birthmark figured into her daughter’s destiny, only that it did.

“What should I call you?” Cindy whispered in the moonlight, re-bunching layers of blankets previously tucked and folded origami-tight by an unseen night nurse. “Lisa Marie?” Fleetingly, she thought of the baby’s father, a charming one-night stand named Christopher, first name only. She’d had other boyfriends since then, other sex in the bathroom stalls at Evangelo’s too, but Christopher was the only one where the math made sense. He had dimples, eschewed cell phones, MySpace profiles, “basically any and all FBI surveillance technology.” He had passed through town ages ago, on his way to the coast—LA, Portland, Vancouver, depending how long his money lasted. He was long gone, and none of this was his.

The next morning, filling out Social Security paperwork before discharge, Cindy impulsively chose Genevieve Marie. Debbie deemed it pretentious. Cindy knew she could never carry herself; she was Cynthia at her fanciest, and only when she was in trouble. But a girl with an Elvis birthmark had sparkle at birth. If the baby inhabited Genevieve Marie from the get-go, maybe it would never seem ostentatious or strange.

Cindy wasn’t born when Elvis died, back in ’77. Debbie told her about it, when they drove Genevieve home from the hospital. “You bet I cried like a baby!” Other people Debbie’s age liked to talk about where they were when Kennedy was shot but Debbie performed this ritual for everyone, icons and intimates alike. She always cried when someone died, whether it was Lois who worked at the pharmacy or Lady Di in the Pont de l’Alma. Cindy sat in the backseat unbuckled, testing the side-to-side mobility of the infant car seat.

“I don’t think it’s supposed to go back and forth like this,” she said.

“I was at work, between tables, running back to the kitchen,” Debbie said, “When Sarah told me— ‘he’s dead! He’s dead! Elvis is dead!’ It was August and I was perspiring, but I’ll never forget it, I felt my blood run cold. That poor man. We didn’t know the part about the toilet until later, of course. Maybe Genny will be a singer?”

They hadn’t been home a week before Debbie carried this line of thinking to its next logical step, musing over ways to monetize the birthmark.

“What, you want to charge five bucks for people to come and gawk at my daughter?” Cindy said, wincing as Genevieve took her raw nipple in her mouth. “She’s not a freak show, Debbie. No way.”

“Did I say I wanted to do that? You’ve seen them well as I have—that tortilla in Las Cruces that had the face of Jesus blistered into it, on the news? Those people were famous, because they shared something extraordinary! And the public wanted to know. Everybody’s always looking for a sign, but especially now.” She paused. “I’d charge a lot more than five dollars.”

“A sign of what?” Cindy asked.

Debbie rolled her eyes. “Any number of things! Evidence of reincarnation. Intelligent design. Divine intervention. That’s not for us to decide. Personally, though, I think it’s a miracle. A miracle with a sense of humor.”

The pay-to-view scheme never materialized, partly because Cindy kept the birthmark hidden.

“That’s just gonna make her hate it,” Debbie said, on a September Saturday when Genevieve was six, as Cindy stuck a pink plastic bandage over El, not because Genevieve had a scrape, but to conceal him from view. Genevieve was going to be in the desfile de los ninos—the pet parade—matching several of her friends in a puffy crop top and circle skirt trimmed with rickrack.

“No,” Cindy said, like Genevieve couldn’t hear them. “What I’m doing is making sure she gets to enjoy being in the parade like anyone else, that nobody stops her, or stares or points or says ‘what’s that?’”

At the time, Genevieve hadn’t minded. She’d jumped up and down in front of the mirror, too excited to be still for the intricate Dutch braids she’d been promised. But she made a habit of carrying Band-Aids after that, even on jeans and t-shirt days. Having one in her back pocket at all times, one she could pat occasionally to make sure it was still there, became her ritual in moments of unease.

Debbie, Cindy, and Genevieve referred to El often amongst themselves, but his potential as an avenue to fame and fortune was largely abandoned, until one afternoon when Genevieve was seventeen. She let herself in through the back door after school, a shoulder season day in March when the weather was turning. Spring was on the wind, winter wasn’t gone—fresh buds and a few blossoms trembled on the gnarled apricot tree that took up most of their postage stamp sized courtyard, a bold bet that hard frosts had passed for the year. Half of the time the tree was wrong.

Cindy and Debbie were sitting at the kitchen table, hands cupped around mugs of black coffee. Genevieve almost never came home to a full house. Debbie worked the slow afternoon shift at the restaurant and Cindy was nine years into pursuing a PhD in philosophy, eight months into an online associate degree in business administration. Most nights she got home from studying at the public library around seven, if she didn’t have her weekly shift at Evangelo’s.

Money was tight. Money was always tight, but it never mattered as much before because Cindy was thrifty and handy; Debbie could sew and cook. It never mattered before because Genevieve wasn’t going to “finishing school for artsy fartsy types,” according to Debbie. When Genevieve applied to RISD, she pretended it was a whim, but assembling her portfolio was a painstaking, laborious process—scanning her best drawings in the library during free periods, borrowing fixative kept in a locked cabinet in the art room to spray dusty charcoal sketches. When the letter came, the one that said yes, Genevieve had been surprised by its lightness, just two sheets of paper, but there it was, in black and white: “Welcome.” She’d been startled when Debbie asked if she’d applied for loans concurrently, downright alarmed when Cindy said that online learning was the wave of the future, why did Genevieve need to move at all?

“Good, you’re home,” Cindy said, as Genevieve stood in the doorway. “We have some news.”

“It’s happening. We’re finally going to be on TV!” Debbie said.

Genevieve started at them, let her backpack fall from her hand to the floor.

“Debbie sent in an audition video,” Cindy said carefully.

“For?” said Genevieve.

“For all of us,” Debbie said. “I mentioned you, of course. It’s a documentary series, very classy, all original content. Small Wonders—that’s the name.”

“Small what?”

“Small Wonders,” Cindy said. “I looked into it. It’s legitimate. They’re owned by a subsidiary of Disney. It pays, Gen. It pays a lot.”

“How much?” Genevieve asked.

“Three semesters at your art school. I looked it up.”

Genevieve didn’t say anything and Cindy went on in a rush. “It’s a week, Gen. They come and do pre-production for a couple days, get everything set up, then film for three days, tops.”

“What do they film?”

“Mostly ordinary stuff, at home with us, going to school. You’ll sit for interviews, they’ll interview me and Debbie, maybe a few of your friends and teachers, and then they’ll feature expert interviews, too. I imagine they’ll want to film El.”

Genevieve’s hand flew protectively to her hip.

Debbie broke in. “You’ll be treated like a star, honey. Valerie says. Valerie, she’s the producer. You’ll like her, she’s so nice on the phone. The series is about regular people—children, mostly—who have something special about them, like you. There’s a six-year-old in Nebraska who had a near-death experience and met the Archangel Raphael, and a teenager in Utah who has visions of tsunamis.”

“I don’t have visions. I have a port-wine stain on my side. And I don’t have any friends to interview.”

“What about that girl, what was her name? Marisol? Oh! They’ll have an astrologer do your chart, too, see if that explains

El. Won’t that be fun?”

None of it sounded like fun but neither did an afterschool job at the restaurant—Debbie’s other suggestion for how Genevieve might pay for college, if she insisted on leaving them. She said yes.

The crew arrived following week. Genevieve had assumed Valerie would look like her idea of a Hollywood bimbo, all bleach and Botox, but she was in her early forties, barefaced but for a bold red lip. She was dressed in a plain white t-shirt and rigid jeans Genevieve could tell were expensive without seeing a label.

“You’ll be easy to shoot. You’re cute as a damn button,” Valerie said, studying Genevieve’s face, fingering the ends of her long hair. “Dimples, too.” Genevieve knew Valerie was flattering her, but that didn’t stop it from working. Genevieve blushed and tried to cover her dimples by pushing her hair in front of her ears so it covered her cheeks.

They started with practice questions in the kitchen. Debbie had cleaned even more ferociously than usual, Swiffering the floors until they shone, pinning all of Genevieve’s best drawings onto the fridge, even though they didn’t really fit, wrapped around the sides. Valerie had an audio recorder, but no camera equipment yet. Cindy sat at the table with them, and there was room for four, but Debbie was too excited to sit so she paced around the small kitchen, wiping and re-wiping the narrow counters with a dishrag.

“How has being born with an Elvis tattoo affected your life?” Valerie said.

“It hasn’t really.” It was true that Genevieve didn’t think about El all the time. Mostly she was accustomed to telling people who asked that he didn’t bother her. “And it’s not a tattoo. It’s a nevus flammeus, and Debbie thinks about him—it—more than I do.”

“Well, that’s not going to work,” Valerie said, switching off her recorder. “There has to be a story for us to tell. Otherwise, what are we doing here?”

“There’s a story to tell here, Valerie,” Debbie said. “Genny— do you need coffee, or something?”

Genevieve was glad Debbie didn’t know about Troy. Troy, who a scant six weeks ago had run his fingertips over El, had been the second person to kiss him—Cindy used to when Genevieve was little, Debbie never did—and the first to lick him, his long, warm tongue tickling Genevieve to convulsions, making her shriek with laughter. Troy caught her mouth with his. It felt like a long time ago now.

“Oh, what about the bathing suits?” said Debbie.

“The bathing suits?” asked Valerie.

Fine, thought Genevieve. The bathing suits would work.

“In seventh or eighth grade everyone was getting bikinis and I didn’t want to because of El,” Genevieve said.

“Go on…”

“A girl in my class saw it once, years before that, on a field trip to a city pool. Third grade, I think. We were changing, she pointed, asked if I’d been burned. I said no, it was a birthmark, but she wouldn’t believe me, she kept saying it was a burn, telling everyone else it was a burn, too. I was Burn Girl for a few weeks. Everybody forgot about it, but I knew they’d remember if I wore a bikini. So, I didn’t.”

“How did being called Burn Girl make you feel?” Valerie switched the recorder back on.

“I hadn’t thought about it in a long time. Sad, I guess. Lonely. Different.”

“Do you feel that way now?”

“No. Not usually.”

“Genevieve. We need to tell a story. Think about when everyone else got bikinis—you wanted to, too, but you didn’t. Sad. Lonely. Different. Do you feel that way now?”

“Sometimes. I guess.”

“Alienation. Agony. That’s what I can work with,” Valerie said. “We can give you an arc—in fact, I think it’s best if we do—that ends in self-acceptance, in maybe even loving your tattoo, if you think that’s possible, but we can’t start there.”

“Seriously, it’s not a tattoo.”

“Right, not technically, but ‘Elvis tattoo’ sounds so much better than ‘Elvis birthmark’—it’s just a colloquialism that’ll track better. We’ll explain it at the outset.” She pointed. “May I see him?”

Genevieve had been dreading this part. With one hand, she pulled up the hem of her sweatshirt. She rolled down the waistband of her jeans with the other. The kitchen was warm, but goosebumps rose to attention along her ribcage. She looked away, at nothing, like she didn’t care, as she felt Valerie bend to look at El, close enough that her breath tickled Genevieve’s skin.

“Wow,” Valerie said. “Remarkable. He really—you haven’t had this touched up professionally, not even at the edges? Damn. You were right, Debbie. He is more lifelike in person. Did you know it’s amazing that this is your first time on TV? Statistically speaking?”

“I know!” Debbie threw her arms up in the air, caught between exasperation and triumph.

Valerie returned on Monday morning with a camera guy called Larry and a sound guy called David Michael. Both men wore hoodies, torn jeans, beanies. They could have been 25 or 45. Valerie miked Genevieve herself, swept translucent mattifying powder over her brow. “I’ve seen makeup artists do it a million times,” Valerie said. “We’re on a bit of a shoestring budget for the pilot season. There. Lovely. Let’s walk to school!”

Ordinarily, Genevieve walked the half mile to school every day in a daydreamy trance, stopping for colorful insects or changing foliage, ignoring the rest of the world, the monotony of passing cars and houses she saw every day. Walking to

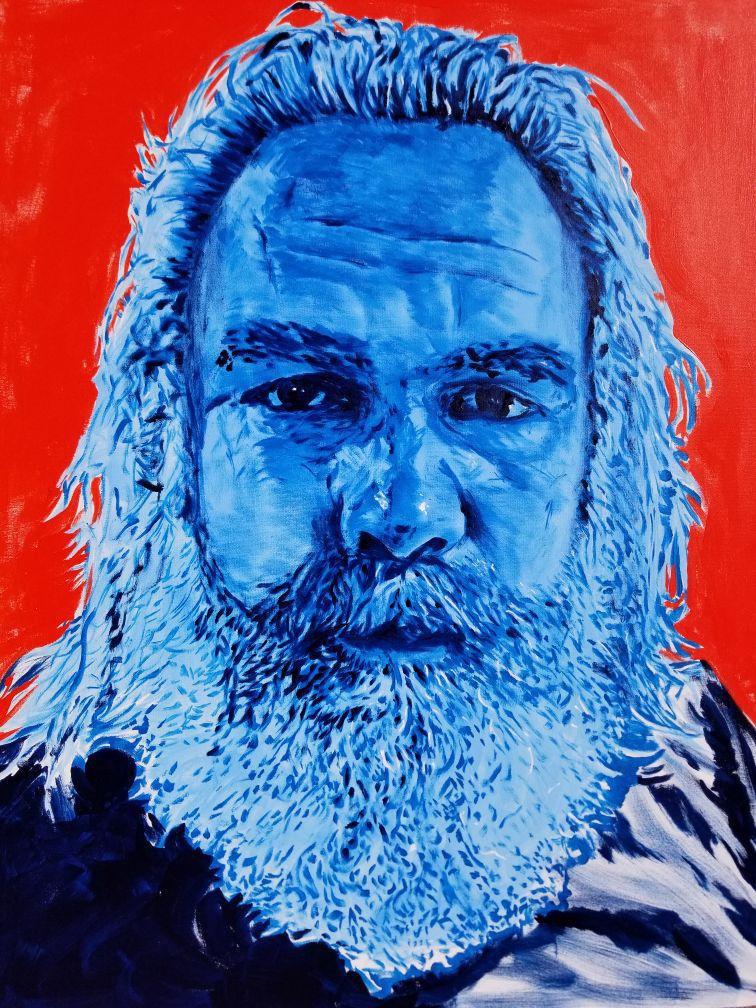

Des Blue By Lauryl Eddlemon

school with Valerie, Larry, and David Michael, this was rendered impossible. Valerie was taking stabs at narration: “On her way to class, Genevieve wonders if today will be one of ostracization or acceptance? No. What about: As she embarks on another day, Genevieve looks like a normal teenager, but underneath layers of pleather and polyester, a secret lurks.”

A passing car honked. Someone whooped out the window.

“What the hell?” Genevieve said.

“Ignore them,” Valerie said. “It’s not you, it’s us. How do you feel right now, Genevieve? Apprehensive? Excited? Terrified? Thrilled?”

“Um. Mildly nauseated, I guess.”

“Nausea! Of course you feel queasy—what’s everyone going to think when we show up at school with you? Why are we here? Maybe you’re under suspicion. Maybe you’re terminally ill? They don’t know!” Valerie squeezed Genevieve’s upper arm and smiled.

“What do you think your dad would think of all of this, you being on TV?” Valerie asked next.

“My dad? I don’t have a dad,” Genevieve said, confused. Why was Valerie asking about her father now?

“Genevieve, everybody has a dad,” Valerie said, chuckling like Genevieve had said something silly.

“Mine’s not around. I don’t know what he’d think.” Genevieve pulled at her backpack straps, cinching them closer to her chest. She had the feeling someone was walking close behind her, though nobody was.

“Do you look like him?” Valerie asked. “Do you know? Wouldn’t it be so crazy if your dad saw the show and recognized you?”

As approached the chain link fence that bordered the edge of the soccer field and a quiet street that ran behind the high school, Genevieve caught sight of a cluster of classmates, vaping and trading tales of weekend glory before first bell.

“Yo, what’s this fancy shit?” said a boy named Cloud. “Bodyguards? You rich now, or something?”

Genevieve laughed like it was a joke she was in on as she approached the group of kids. Belatedly, she wondered if she should’ve asked the principal if Valerie and the crew could accompany her to school. But Valerie must’ve already done that— securing permits and signatures on talent release forms.

Aimee, a girl Genevieve hadn’t hung around with in years, called out to her:

“Hey, Burn Girl!” Aimee looked embarrassed, excited, emboldened by the smatter of laughter that followed. “Did your dad really brand you with a cattle prod when you were born?”

“Genevieve!” Amber, a girl she’d spoken to maybe twice. “Is it true that your mom let someone tattoo you when you were a baby in exchange for cheap meth?”

Genevieve stopped at the edge of the street, feeling faint. This had been a mistake.

“Larry!” Valerie hissed. “Get her face! Zoom in!”

Genevieve swallowed, thinking fast and then not thinking at all. Turning on the balls of her feet, grateful for the double-knots on her sneakers, she spun on the frayed edge of the grass, roughly shouldered past Valerie and David Michael, made for an alley at the end of the block that she knew emptied into a ravine choked with river willows and Siberian elms.

Genevieve was not athletic. She would jog slowly when laps were required in PE. Her quads seized in surprise as she willed her legs to move beneath her, stuttering into motion. She

Mother of Playfulness By Karen Eisele

had a moment’s head start during which Valerie was stunned, but when she turned her head to glance behind her, there was Valerie in pursuit, Larry a stride or two behind. David Michael was still standing in the middle of the street, holding his sound equipment and Larry’s camera.

“Genevieve!” Valerie yelled. She was in decent shape, but her Italian loafers, leather-soled and slippery, struggled for purchase on the gravel. “Tell me how you’re feeling! Don’t worry, I’ll get those nasty little bitches to back the fuck off. We can’t pay you if you’re not on camera!”

Genevieve didn’t turn around again until she’d cleared the ravine. She made a split-second decision not to hide in the reedy trees, too dry and rustly. She was about to dart across a busy four-lane street against traffic when instead, she veered right as though drawn by a gravitational pull, though it was just her gut, a second or two ahead of her brain. She was able to squeeze herself through the iron gate of an overgrown cemetery—inactive since the thirties—that ran unnoticed alongside the street and took up a scant city block.

She ran between haphazard rows of mismatched grave markers, wooden crosses and solemn angels. She dropped to her knees and crawled to a granite headstone, scanning the cuts in the stone before she sat with her back straight against it. Jose Coriz, died in 1917, only 25. Genevieve wondered if he’d been handsome. Back then, he could’ve been her boyfriend—it wouldn’t even have been weird that he was so old. Breathing hard from running but trying to control it, Genevieve imagined Jose, dark-eyed and shy, dying of consumption in a sanitarium. She wouldn’t be allowed to visit for fear of infection, so she’d stand outside his window and weep, and when he died, she’d visit his grave dressed all in black, watering the hardy lilacs she planted there with her tears. Not for the first time, Genevieve wished she could cry on command. Her lungs seized, wanting to inflate all the way but collapsing against the cage of her chest as she tried to hold still.

The first time she showed El to Troy, three months ago now, he’d whispered, “Fucking dope,” his hands pausing on their way down her waist and over her thighs. They’d lain next to one

another on Genevieve’s single bed, atop her faded dahlia print duvet, awash in winter sunlight. Debbie and Cindy wouldn’t be home for hours. “I didn’t know something like this could be real,” Troy had said, smiling up at Genevieve. He’d horrified her by pulling her panties down and burying his face in her pubic hair in one fluid motion. It was only the second time they were hanging out, Genevieve would’ve done something about said pubes—tried to shave them off, probably, was that what boys liked?—if she’d thought Troy would end up in her underwear, but he didn’t seem to care. He was enthusiastic and surprisingly adept. Afterwards, when she’d tried to cover herself with the quilt, Troy had gently staid her hand, taking one last look at El. He hadn’t mentioned her drawings, which covered the walls of her room from floor to ceiling, and some of the ceiling itself. The drawings nearest them were derivative of Escher, sure, staircases that led nowhere, insects rendered life-size, but some of them were good, too, like the nimbus clouds over the bed. “What do you think it means?” Troy had said, fondling El. Genevieve had pulled into herself, sucking in her stomach, willing Tory’s hand away. “I don’t know.” She’d flipped over onto her belly, where El was out of reach. Troy had looked disappointed. The next week, he stopped talking to Genevieve, stopped looking at her in the hallway, didn’t respond to texts. After the third text she tried, she’d had to stop sending them. It was painfully clear he wasn’t going to write back. As a last-ditch effort, Genevieve had written Troy a long email, asking what had happened, overexplaining, making herself vulnerable and pathetic. He hadn’t responded to that, either, and Genevieve knew now, with a sureness that frightened her, that they’d never speak again.

Atop Jose Coriz’s grave, the more Genevieve tried not to move, the more difficult it became to ignore that El had started to prickle on her side, an itch she shouldn’t scratch. She wanted to dig her nails into El, give him a good raking like she did sometimes, like she did to every centimeter of skin on her lithe, pimply body, all gooseflesh and whiteheads. Even gentle, exploratory touches usually ended in something rougher—a nail-raking that left marks—but she thought it did her more good in the end, a no-nonsense cleansing. Her fingers found a sliver of belly, exposed it to the cold.

“I don’t see her!” a man’s voice carried on the wind, above a river of traffic. Genevieve froze, hand in the soft of her belly.

“Damn it! We can’t keep looking. She could’ve gone anywhere at this point.” Valerie.

“Should we get the mom?” Larry asked. “Shit. Is this gonna be like Utah?”

“No,” said Valerie, “Definitely not. We can’t afford another Utah. Call Debbie—the grandma. Mom is out to lunch.”

Unbidden, never when nor for whom she wanted, tears sprang to the corners of Genevieve’s eyes. She risked movement to wipe them angrily away with her sleeves. How many times had she thought the same thing to herself—that her mother didn’t have both feet on the ground, that she existed in a private realm of piled, used textbooks. All the one-sided conversations Genevieve overheard while a headphoned Cindy chatted with people she knew only online. Even when Cindy said she was listening to you, her gaze was just beyond your shoulder, a place Genevieve had never been. Debbie’s arms were always open; she would have loved to have Genevieve as a protégé, but that would mean working at the restaurant, constantly scheming for something better, risking reaching a time when you didn’t actually want to leave the restaurant at all.

I could lie here forever, Genevieve thought. Or, I could go home at night to sleep and eat and pee in a toilet, but come here every single day. For a moment this felt like a tangible solution, a real-life plan, becoming obsessed with a dead boy. At least it offered focus. She could pretend she needed to visit the graveyard for a research project, something to do with community history, and maybe she could do that, too. Collect every shred of information she could find about Jose Coriz, become as close to him as possible. If you believed in parallel universes—and Genevieve wasn’t sure that she didn’t—it seemed plausible to find a plane on which Jose still existed. Maybe Genevieve needed only to locate the right lens.

She craned her neck around the side of the headstone, watched Larry and Valerie disappear into the tangle of the ravine. She was seized by a sudden pull to get out of the cemetery

Exercise Log For The Hairried Housewife By Laura D’Alessandro

she’d wanted to haunt moments before, away from the cold stones and relentless spring sunshine, and most of all the wind, spreading pollen with strong, unyielding gusts that existed for the spreading alone. The urge to leave was singular and pure, a particle carried on the breeze and blown into her ear. She rose from Jose’s grave filled with a potency of hope and purpose known only to the living—there was an Allsup’s nearby, and it had an ATM.

Debbie was in the kitchen, triple-checking the burners on the stove were off before heading to the restaurant, when she got the call. They still had a landline, mounted to the wall by the back door. The cord was six feet long, so you could reach every corner of kitchen while staying on the phone, sometimes winding it around your body in the process.

Valerie said Genevieve ran away and Debbie sighed heavily, but she wasn’t surprised. She understood why Genny ran. Her granddaughter was shy and self-conscious to begin with—adolescence hadn’t helped—and she’d never been a natural performer. Not like her mother, who had danced ballets and belted out living room concerts for years when she was a little girl.

For the life of her, Debbie couldn’t understand why Genny didn’t want to use her God-given gift. Genny was the one who wanted to get the hell out of Dodge, and she was a smart, and still somehow, she didn’t see it. She failed to grasp that this was exactly what Debbie had been doing her whole life—trying to forge her paths out. Genny didn’t understand that not everybody was given something to help them along. Debbie hadn’t been blessed with any extras. She was certain Genny’s darker-than-usual malaise was due to the boy Debbie had encountered on the narrow lane to their house a couple months back when returning from work, a boy who’d nodded at her politely. She’d seen the panic in his eyes and knew exactly where he’d been. When she’d gone to Genevieve’s room to confirm her suspicions, she’d found the bed mussed and her granddaughter When Genevieve turned her head and the headlights swept her face, she looked young and small, as only Cindy had known her. Be cool, Cindy said to herself. Be cool. Don’t scare her off.

starting dreamily out the window, her cheeks flushed.

“Hello? Debbie?” Valerie said on the line, sounding far away.

“Tell you what,” Debbie said. “Meet me here in twenty minutes. We’ll figure it out.” She hung up and dialed Cindy. “Valerie’s coming over. There’s been an incident with Genny. I have to go, I’m already going to be late, but I told Valerie you’d be here.”

Cindy cranked the RAV4’s windshield wipers to full blast, but they did little to help her see through the heavy snowfall. The squall shouldn’t have caught her off guard—they happened every spring, sometimes as late as May. Genevieve wasn’t answering her phone or responding to texts, but Cindy kept calling all the same. It was late afternoon, coming up on dinnertime, and the sky was slate with heavy clouds.

The RAV was good in the snow, Cindy would give it that. Debbie had bought it because she read somewhere once that Tom Hanks drove one, but it was good in the snow. Nobody else was on the road. Cindy drove through a section of town that was changing quickly. When she was growing up, it’d been a vast patchwork: fields and vacant lots; water treatment sites; a cemetery, bordered by bleak, industrial streets, a no-man’s land where kids went to fool around and smoke weed.

Now, the area was “revitalizing.” That was what the City called it. Contemporary lofts and industrial-chic bars. They’d kept the graffiti, the crumbling WPA bridges, but they polished the concrete and drove around in Teslas.

Inching along, Cindy saw a figure in a hoodie walking on the shoulder of the road, hunched against the wind. It was too much to hope it was Genevieve. Cindy had already seen her daughter’s face in a dozen strangers that afternoon, desperation giving her a fleeting moment of recognition before she saw it wasn’t Genny at all, but an old man with a yellowed beard, a woman with pinched eyes.

But it was Genevieve this time. Cindy knew that hoodie—it had cost $125, some ridiculous eco-tech brand on the rack at REI. They’d fought about it. Genevieve had pleaded and said she’d wear it every day. Cindy had bought it for Christmas. When Genevieve turned her head and the headlights swept her face, she looked young and small, as only Cindy had known her. Be cool, Cindy said to herself. Be cool. Don’t scare her off.

“Hey stranger,” Cindy said as she rolled down the window. “I don’t know if you noticed, but it’s snowing. You want a lift?”

Genevieve hesitated, but she got in the car, sodden, nose red and running. Cindy put the RAV in gear, determined not to mention Valerie or the TV show, but Genevieve said, “Wait. I want to show you something.”

She pulled up her shirt.

“Oh!” Cindy gasped.

Where El had been was a flowering apricot branch inked in fine black lines. The tattoo looked blurry under a layer of taped plastic, like a waterlogged sheet of paper drowned in a fountain.

Cindy recovered quickly. She followed with, “It’s beautiful,” on instinct. She didn’t know yet if it was beautiful, could not look at the tattoo as separate from her daughter, the person whose fingerprints had formed by pressing up against the sides of her womb.

“Really?” Genevieve looked scared and guilty. “I cleaned out the checking account. The guy wanted an extra $100 since I’m a minor.”

At this, Cindy’s breath again caught in her throat. Debbie kept stashes of cash around the house—Cindy performed a quick mental inventory. Behind the loose cabinet panel in the

3D By Laura D’Alessandro

kitchen. Taped to the backside of a framed Manet print in the hall. Inside an old cough syrup bottle. She could pick up more shifts at the bar.

“Really. It’s beautiful.” Cindy grasped that she needed to say this again, might have to say it many more times. “You’re getting a job at the restaurant, though.”

Genevieve nodded, looking down. Maybe she’d anticipated this.

“I kept his eyes,” she said. “El’s. You can barely see them, but I kept them.”

Cindy slowed down. She turned away from the road and looked closer. There they were, buried deep in the unfurling petals of the biggest blossom, a secret in plain sight.

“I wasn’t trying to do something terrible to you,” Cindy said. “With Small Wonders. If I could buy you everything you wanted—” Why was it easier to say this than pay for college? “I would, but I can’t, so I’m looking for other ways. That’s all.”

Genevieve nodded. Cindy kept driving. The tattoo was beautiful, she decided. She hadn’t been lying. It reminded her of an intricate botanical specimen, drawn in the days before photographs. When she thought about El, she felt a gentle tug behind her sternum, an ache like the one she felt when she thought about Genevieve as a two-year-old, or at five, or ten. That person was gone now, even as she sat in the passenger seat, and it made Cindy almost unbearably sad. Was this terribly stupid, considering Genevieve was—relatively—unharmed? Cindy already missed El, but he wasn’t hers to miss.

“Are they going to be there when I get home?” Genevieve asked at a red light. “Valerie and them.”

“Hell, no. I sent them away.”

“You sent them away?” She seemed surprised.

“Well, yeah. After Valerie told me what happened, even though she was trying to make it sound better than it was, after she said that they chased you—I told her where she could go.”

Genevieve furrowed her brow. “Is Debbie mad?”

“She’ll get over it. Having you at the restaurant will help.”

When they pulled up in front of their house, it was dark. Debbie had gone to bed absurdly early to make a point. The porch light was on, though, so she wasn’t feeling too spiteful. With the motor running, the RAV was warm and dimly lit, like a cave dug from a snowbank. The apricot’s blossoms, the ones that had already burst from their maroon shrouds, were slowly disappearing. The branches grew heavy and bent toward the car.

“Our flowers,” Genevieve said.

“It could be good, actually,” Cindy said. “If the weight isn’t too much. Big polycrystals like this mean it’s not too cold. And they’re soft. They’ll insulate the blossoms, like little domes. With any luck, we’ll still have fruit.”

“Hmm.” Genevieve leaned her head on the window, now cloudy with condensation. She drew lines in it with her pinkie. She didn’t look at Cindy, but she didn’t unbuckle her seatbelt or move to open the door, either. Cindy was glad. The moment they left the car, the spell would be broken. When it happened, she didn’t know how the world outside would be different, but she knew it would be changed. Already, Cindy sensed invisible currents shifting in the air around them, gathering strength before crackling quickly out of sight, lighting in the corner of her eye. All the windows were foggy now, and it was impossible to see outside. A snow globe effect: trapped, in a good way. Maybe safe. Cindy was warm in her coat, on the edge of drowsy. She felt like talking.

“You were born on a night like this one,” she began. “Debbie was driving too fast and it was snowing like crazy.”

Staying Afloat for a Moment By Stephanie Gonzalez

Hickman 1 By Josh Hickman