16 minute read

Egg Peter Wakeman Schranz

from TEXLANDIA 2022/23

Egg

Peter Wakeman Schranz

Advertisement

Now let’s say you’re asking why I passed so well for a human on land, and so well for a fish in the sea. I have no interest in explaining the perfectly simple reasons for this. Reasons irrelevant to anything that matters even slightly. If, however, because of your obsession with the insignificant, you insist, then I would refer you to a short but thoroughly informative paper by my good friend Elisabeth Frege: “Hox Cluster Expression in Squaliform Hybrids,” in this quarter’s issue of the Journal of Atlantic Genetics.

If you refuse either to read the paper or to trust the things I say—the things you may not understand—you are responsible for your own curse.

I’ll ask you forgive me my defensiveness. I have learned bitterly that nobody likes to be impressed, and that most try very hard to avoid it, even though the paper will answer all their unimportant questions, and was written by my very good friend.

A month or so ago, I hatched from a lonely black egg on the sandy bottom of New York Harbor, a harbor which many others have so well described that I would just as soon not bother. I saw no mother, no clutch of siblings, nor even a hungry stranger in that water so brightly stained from the streetlights and the moon. I hatched expecting a mother, hoping for siblings, and dreading a stranger, but I slid from my egg in complete solitude, and gazed above, to the wavering shafts of light that wriggled down towards the floor of the harbor.

I swam up to the lights, and soon approached the underside of a boat. I thought it might be my mother, what did I know? In my hox genes or something I understood being in a family and I knew how pleasant it felt, and I knew a few other things likewise.

This boat was one of those so constructed that, even though there is a square diving-hole in the bottom, it doesn’t sink. I swam up to that hole, and climbed from the wet and frigid place into a shockingly comfortable little cabin-like bilge. As I stood, fully clothed, I beheld, observing gleefully at the lip of the diving-hole, the most beautiful woman I had ever seen in my entire life. She and her two friends had been playing cards at a little table hanging from the wall. When they saw me, she stood. Her friends stayed and chuckled, but she approached.

“Got him!” she said, for it seems that they had been waiting for me, or at least she had.

“I’m not interrupting, am I?” I asked.

“Of course not,” she said. “What is your name?”

“You know perfectly well that I have no name,” I answered, not understanding precisely what I was talking about.

“My name is Elisabeth Frege. Elisabeth with an ‘S.’ I have come from Germany to find such a specimen as you. I have a great deal to ask you, if you don’t mind.”

She introduced me to her friends, I suppose because she didn’t want to ask me questions in the presence of strangers. They themselves must not have considered me a stranger, since they were taking pictures of me already, and of themselves. While she said their names I was trying to remember a card trick I knew. The best I can recall is that one of them had frizzy black hair, and the other was exceedingly skinny.

“I’ll show you a card trick,” I said to Elisabeth as I neared the cards.

“You can’t do that,” her skinny friend complained. “We’re in the middle of a game.”

I was disheartened to learn that they were more interested in their game than the fact that I knew a card trick despite having slid from a black egg just moments earlier. Maybe they all knew about the unparalleled precocity of my breed. Certainly Elisabeth already knew, but then what about me did she want to study, if not my characteristics?

“You’ll love it!” I insisted. “Let me show you.” The players had arranged the cards into four piles, their own face-down, the middle face-up. I pushed all four piles irrevocably into one.

“What are we supposed to do now?” said Elisabeth’s blackhaired friend. At the time I thought she was asking me what they were supposed to do to get the card trick underway, but later I realized that she was asking Elisabeth, and that she meant in general.

I got nervous when I realized, hunching over the table, that I’d mixed the face-up and face-down cards, and would have to reorient them all before I could start the trick. “Let me just fix these first,” I said without looking at anyone.

“Elisabeth,” said her skinny friend, “It’s getting pretty late.”

“Yeah, we’d better go home,” said the other.

At that naive period of my life I still couldn’t figure out why they didn’t care about my card trick. Elisabeth walked them up to the deck and I sat by myself at the table in the wall. As I tried to rearrange the cards I heard her say goodbye and apologize to them at the gangway. She returned presently, and sat with me at the table. “Thank you for waiting,” she said.

“Why didn’t they want to see my card trick?”

“I’m not sure. My guess is that they didn’t want to pay very much attention to you.” A month or so ago, I hatched from a lonely black egg on the sandy bottom of New York Harbor, a harbor which many others have so well described that I would just as soon not bother. I saw no mother, no clutch of siblings, nor even a hungry stranger in that water so brightly stained from the streetlights and the moon.

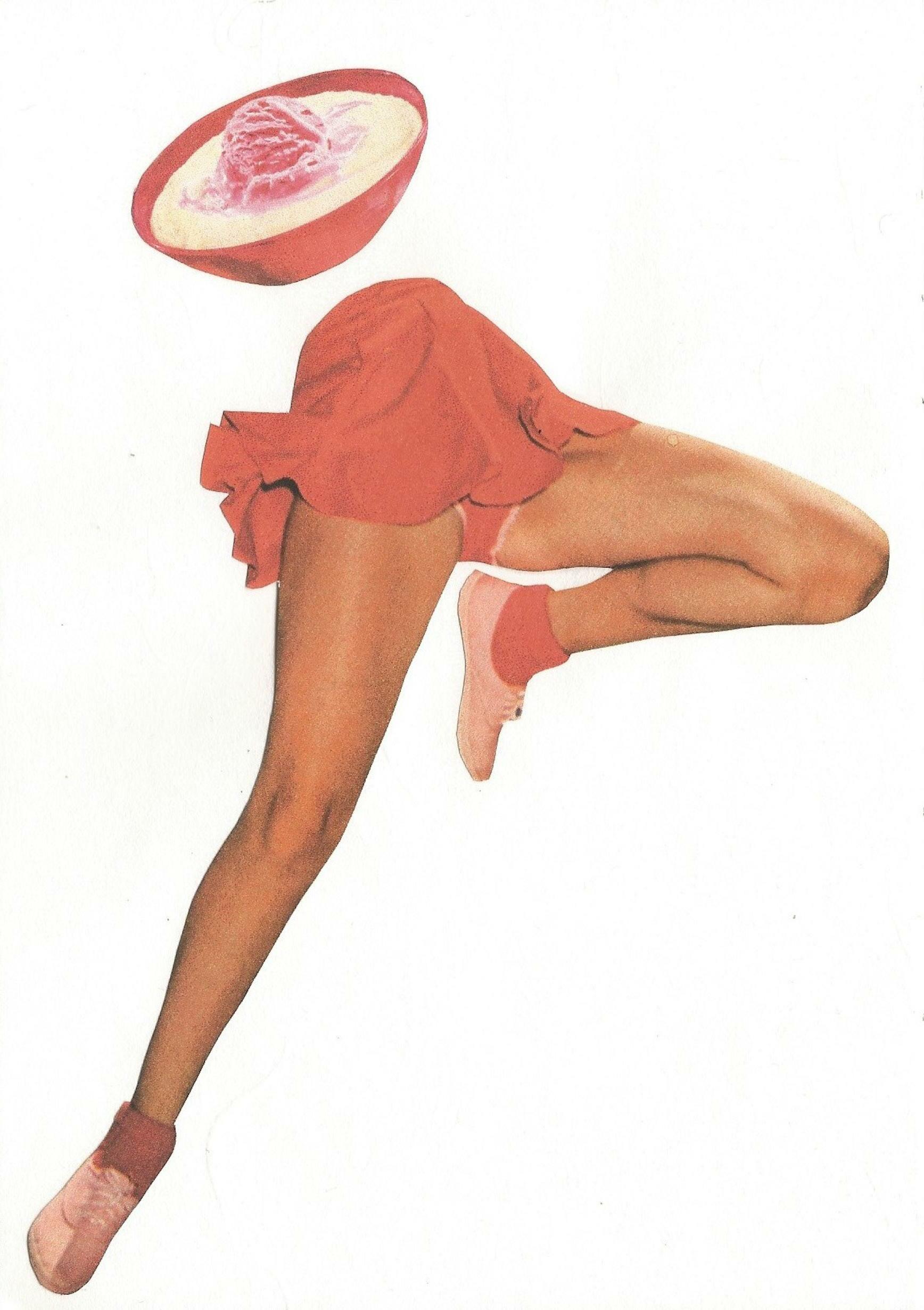

Ice Cream Legs By Anastasia Kirages

Cultural Heart By Daniela Pasqualini

“But don’t they want to study me?”

“No, I want to study you. They’re just my friends. They study clams.” I quietly finished rearranging the cards, and Elisabeth said, “You can show me the trick if you want.”

I thought about it for a second and slid the deck towards her. “No, thank you. Now that I think about it, it probably would have been even more annoying if I’d actually done the trick.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Because I think if you do it right then some of the cards actually disappear for real and the deck is ruined.”

“That’s very considerate of you, then.”

“Should we get married?” I asked her.

She laughed and said no at the same time, in a way suggesting that my question supported something she understood before then only in theory. “I just want to talk to you,” she answered.

And so she did talk to me. She asked me how someone as young as I was knew a card trick, and how I learned such good English. She said she’d started studying English in elementary school but still ended up with a German accent. She asked where my clothes came from, and a million other questions whose answers don’t make any difference at all, but appear in her paper, which she asked me to proofread.

We went about like this for a couple of weeks, and she let me live in the boat and leap during mealtimes through the square diving hole, and pry open clams with my teeth. She just wanted me to answer her questions, and knew expertly that I would always swim back to the boat to do so after I fed.

One day, one of her questions was particularly personal, which I took to mean that she was finally becoming impressed with me. “I know you don’t have a name,” she said, “But would you like one?” I told her I would, and she said, “What would you like your name to be?”

“What about Boat?” I suggested, quite reasonably I thought.

“I don’t think so,” she said.

“Well, then what about Egg?”

“No,” she said. “That’s not really how names work. We’ll keep thinking, maybe.”

I had asked Elisabeth every day to marry me, because I didn’t have a family and she and I would have been great together if only I had allowed myself to be more impressive. On the day we spoke about my name, she finally said something other than no, although that’s still what her answer amounted to.

“There’s a documentary showing this afternoon,” she said. “I think you ought to go see it. It’s about you.”

“Me?”

“Well, not you specifically. It’s about your kind, I mean.”

“Are you coming with me, Elisabeth?”

“I can’t. I have quite a busy day, and I won’t be back until later this evening. I bought you a ticket, though. Please go. The documentary is not very technical, if that’s what you’re worried about. It’s nothing like my paper.”

“I’m not worried about that,” I assured her. “I’ve just never been off the boat before, certainly not by myself. Aren’t you worried that I’ll get lost?”

“If you don’t get lost in New York Harbor, you won’t get lost on New York Avenue,” for this was the street where I would find the theater.

“But where are you going, Elisabeth?”

“First to the library and then I have to do a lecture, which I would invite you to, but I’m sure you wouldn’t understand it, even despite your unparalleled precocity.”

“I could understand it,” I said desperately.

“I bought you the ticket to the documentary already,” she said. “I will be very sad if you don’t go. I will see you this evening.” She gathered her purse, scribbled the directions to the theater on her notepad, and left me and the ticket alone in the boat.

I gave her a head start so I wouldn’t have to refute the goodbye we’d just accomplished, and then followed her directions to the theater. I walked across the world-famous New York Bridge, at the end of which the theater stood, and I became conscious of how tiring it was to walk on land, and to be ignored by those who passed me.

I was early to the documentary, and before it started I watched the last five minutes of E.T. My companions in the dimming room were distant: two teenagers making out in the very back row, and not far from them, an elderly couple holding hands, which is the senescent equivalent of making out. Of course I was front and center.

I admit that the walk made me very tired while I watched the presentation, and there were countless periods in the theater where I must assuredly have been asleep. The first part I remember was about a medieval geographer. The subject of the geographer was brought up to introduce some important point about my breed, but all I can remember is that they said how, whenever he was on land, he was convinced the earth was flat, and that whenever he was at sea, he was convinced it was round. I don’t remember how they tied any of that into the main subject, but if you must know, then you should be ashamed of yourself.

Another thing I remember from the documentary is when it said we were half extraterrestrial and half dog, or half human and half dogfish -- I know that one of those combinations was mentioned, and even though I was nodding off a little, I’m ready to swear that they both were. Our mothers are always either from Earth, or extraterrestrials capable of laying eggs on the sea floor of Earth. It occurred to me that I may have dreamed some of this as a result of my exposure to the last five minutes of E.T.

Either way, the documentary provoked a great sorrow in me. If what I’d understood from it was even close to the truth, then there was no reason for anyone even to take me seriously, let alone take my hand in marriage.

I left the theater and it began to rain as a result of my emotions. I reflected most mournfully on the parts of the documentary that I remembered, but my reflection began only upon being finally outside again. The unquestionable narrator had explained that each individual of my kind, after learning that it’s an alien or a dog or whatever, returns to the sea and hides under the sand. I felt such despair about my fate that I lacked the strength to resist it, and so made my way back to the harbor.

I crossed the bridge again and gazed sadly down into the rain-tangled water of New York River. Yes, I thought, I’ll have to return to the sand again. The only reason I agreed to see the documentary in the first place was to obey Elisabeth. It made perfect sense to me that if I did whatever Elisabeth wanted, then she would love me. I couldn’t think of a more reasonable theory. On the other hand I also thought it would be reasonable to name myself Egg.

During my walk back I kept remembering more of the documentary. It sketched the entire life cycle of my lonely kind: first our mothers lay and abandon a single black egg, and so we never know our parents, or learn from them how to behave, and thus almost all of us find it impossible to court, though we all try. We fall in love with whatever animal we see first, and any incestuous difficulties are solved by the behavior of our mothers to lay one-egg clutches and then to rush off.

Those of us who fail in courtship (that is, almost all of us) return to the sea and hide in the sand. That’s what I remember.

Gulf Waters By Julia McLaurin

Midnight Snack By Julia McLaurin

As I approached the harbor, I glimpsed Elisabeth and her friends entering a lecture hall, and naturally I followed. It was packed and undisciplined inside, and I lost Elisabeth in the crowd. Soon someone approached the podium and said something in German, and everybody took their seats. Elisabeth took the podium next and began presenting a PowerPoint. I was interested in standing up and saying hello to her from the audience, and asking her how she was doing, and telling her that I liked the documentary, because telling her I liked it would make her like me. I lost my courage though, and learned a rule, because a man with a big hat in front of me was talking on his phone until an usher came and whispered something angrily to him.

I didn’t know what Elisabeth was talking about, but every once in a while on a slide the word “Foetusfische” appeared next to an arrow-filled life-cycle diagram or some kind of a graph, and Elisabeth would sometimes say the word. Sometimes she would say something and the entire audience, excluding me, of course, would laugh. I surmised that they must all have known German, too, or that they were laughing at the sound of the German language, which despite the laughter’s intermittence, is uniformly humorous.

Elisabeth had included slides with some pictures of us on the boat, of us playing cards, and of her friends laughing at me and getting mad at me. There was surely material in her lecture that she’d left out of her paper.

I hadn’t really taken any of the alien business in the documentary seriously, but as I listened to the language everyone at the lecture but me spoke and understood, I thought about how, generally, aliens never seem to realize that there is more than one species on earth, and that humans speak more than one language. This is because, on every other planet, there is only one species, such as “Martians,” and they only speak one language, such as “Martian.”

After the lecture I couldn’t bear trying to get Elisabeth’s attention. I was possessed by the overwhelming urge to leap into New York Harbor and hide under the sand and never again expose my person to the vision of another living thing. I made it my quest in the short walk to the water to do so, not because it was an unavoidable stage in my life cycle (the documentary and, perhaps, Elisabeth herself, had tried to assure us all of that) but because it was avoidable. Where the documentary and the lecture part ways, however, is at this point: the documentary made me feel truly, utterly powerless, whereas the lecture made me feel, if not powerful exactly, since I didn’t even know what Elizabeth was saying, at least like an active participant in my own life, because I knew she was talking about me, and the things I do.

I leaped into the harbor, swam down to the floor, and flailed at the sand until I felt that it sufficiently covered me.

I want to put a stop to this nonsensical theory, that at the last stage of my life I am certain to give up on love and go hide in the sand -- I will put a stop to it not by refusing to give up on love or refusing to hide in the sand, but by giving up and hiding even though I don’t have to.

I’m hiding even though Elisabeth was nice to me and waited in her boat for me to hatch. I know she probably made fun of me during the lecture, but she was probably also saying nice things. To you it looks like I succumbed to fate after all, but then again, you’re not even real, you’re just an imaginary, potential debate-adversary whose objections I am mentally anticipating. Even here I can’t honestly be defensive, since this is all just my memory. I’m not in front of an audience at a lecture. I’m the only one here, under the sand, but at least I know how difficult this choice was. It was difficult not only because it wouldn’t convince anyone that I have triumphed over self-sand-interment, but also because I am now so desperately inclined to try to find Elisabeth, and tell her I was at the lecture, and ask if she saw me in the audience, and see if she’ll tell me what the PowerPoint meant.

No, I’m not going to do any of that. I’m going to hide right here under the sand I hatched on, and wait for whatever is supposed to happen, practicing what I will say, I suppose, not that anybody will ask. Even so, I know what it means to be buried, in spite of my hope that I won’t ever die.

Everything is Bigger in Texas Julia McLaurin By

Santa Fe Elk Julia McLaurin By