4 minute read

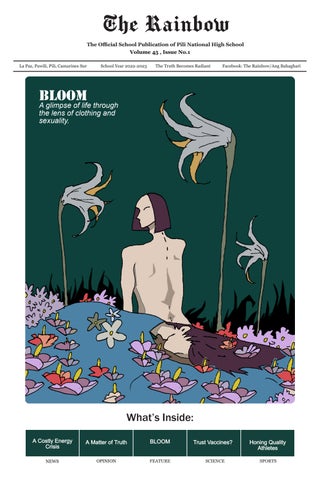

BLOOM

A glimpse of life through the lens of clothing and sexuality.

Artwork and

Advertisement

Written

article by Frances Vincent Decena

Like innocuous voices, clothing speaks to us: its beauty doesn’t revolve around the aesthetics of whatever you wear, but solely on the story that tells why youwearit.

Whenever Gilary Salvino and Jeremi Navales, both transwomen who go to PiliNHS, come to school on Monday to Friday, they wear feminine tops, mid-length skirts, and anyotherthingthatspells the word slay: appearances, which once seemed small and ordinary, had now come to glow a brighter meaning.

And meaning, that is, can be subjective—what matterstousmostdoesn’t necessarily mean that it will constitute the same value to the people around us. In contrast, though,that’sthepoint— thattheydon’thavetosee its value, but they just have to respect and comprehend that it matterstous.

Ever since childhood, Salvino and Navales had already known that they weregirls.Althoughborn in the wrong gender, this fact was true in their hearts.

Before they outed themselves, it was as if they were piecing together the broken fragments of a puzzle to which they had now come to know as themselves. It was as if looking at the sun felt better than looking at a mirror.

“It felt like there was something wrong with me. Like, I didn’t really feelthatitwasmewhenI lookedatamirror.Itwas as if I tried becoming a person who wasn’t me,” follow terrorizes students from marginalized communitiestofitintoits cookie-cutter model of conformity. And it’s no secrettoothatwehaveto findotherwaystoexpress ourtruthsevenifitcauses people to turn a glaring eyeatus.

One thought lingered in Navales’ head: “I really wanted to pursue what my heart was aching, dreaming to have. Because if I hadn’t, the thought of ‘Why didn’t I just do it?’ would linger in my mind and poison me.”

When news broke out that LGBTQ+ kids were now allowed to wear the uniforms that they preferred, both Navales and Salvino were beaming with bliss— “It was our dream come true.” just ignored them,” she continued.

Not always, though, do people like us have to suffer the extremes of beinganLGBTQ+kidin an environment that is deeply appalled by our existence. There’s hope, and Navales’ story perfectly exemplifies this:

“The first time I wore feminine clothes, I felt scared. Anxious. I kept thinking that maybe the people at school would make fun of me— degrademeforbeingtrue tomyself.”

“ButIwaswrong,”she continued.

Salvino exhumed. “It felt like I was faking myself when I wore men’s wardrobe.”

Navales, on the other hand, entailed that she lost her “confidence and eager to go to school” wheneversheworeattires that didn’t suit her gender.

“MyheartbrokewhenI wore uniforms that were meant for men. I was a girl at heart, but I was forced disguise myself in the skin of masculinity. My confidence and eager togotoschooldrastically faded—butIkeptfighting and fighting because my parents needed me,” she told.

“I had to endure all of that because I loved them.”

It’s no secret that the norms and rules that society enforces us to

Their journeys to becoming themselves, however, was never smooth: their lives rotated in a spiral of doubtandfear,aresultof the antiquated, heteronormal rules that society enforces. The injustices that they were forced to face felt like a beating of a thousand cuts—peer-based discrimination, passersby talking behind your back, ill-conceived eye rolls on crowdy streets. To some LGBTQ+ kids, this is the landscape that welivein.

When Salvino was asked how she felt when she started to transition, she told us: “My family was really happy to see me transition. I wore short shorts, crop tops, andthingsthatIhadlong adored.”

But I only ever heard harmful things when I stepped outside of our house. One of our now subject teachers even calledme‘abnormal’and that people like me had really affected their dignity in a negative way,” she added. “But I knew that I wasn’t stepping on anyone with what I was doing. So, I

“The first time I wore feminine clothes to school, my entire class kept cheering for me. Theywerereallyproudto see me as I am. Even the boys at my class treated melikeagirl.Itmademe reallyhappy.”

Sometimes, a loving homecanevenbeenough to let us feel that we are valid.

“Ifindsafetyandloving in my home—it was the people there that cared forme.Thatsawme.And thatshapedmetobewho I really am,” Navales said. “This was where I first came out and got accepted without being discriminated.”

As tender as open wound,wefindourselves a common ground—that we are more than just an afterthought of an insulted conversation. To us, clothing doesn’t conceal,itletsusbecome visibleintheshadowthat injusticecasts.

WhenIaskedSalvinoif she felt safe in her environment, she deeply replied:“Idon’tthinkI’m safe.”

“EverywhereIgo,Ihear people saying stuff behind my back. I’m oftenfrightenedbyit.But I choose to make the places I go ‘safe’for I’m the only one who can makeitthatway.”

Hours spent waiting in line, surrounded by strangers wearing masks of different colors. They didn't know what was in it, yet they let the needle pierce their flesh in hope that it'd protect them from the enemy hiding in plain sight.

A substance used to stimulate immunity to a particular infectious disease or pathogen, vaccines mimic the virus or bacteria that causes disease, and triggers the body's creation of antibodies. The antibodies will give protection once a person is infected with the actual diseasecausing virus or bacteria.

On march 1, 2021, ex-president Rodrigo Duterte initiated the vaccination program in the Philippines. It was the day after the arrival of first vaccine doses which were donated by the Chinese government.

The program was approved by most Filipinos. For months, covered courts, schools, and hospitals were filled with queues, people waiting to get vaccinated to protect themselves from the harm of the spreading virus.

As of march 15, 2023, around 79.2 million Filipinos were already fully vaccinated, including the ones who received single-dose vaccines. 75.7 million people, on the other hand, were still waiting for their second dose, and 24.2 million already received the booster shot. However, the remaining countrymen are hesitant to get vaccinated. From the previous PulseAsia survey that was released in January 2021, 47% of Filipinos said they were unwilling to get the shot if the vaccine was available.Among those unwilling to get vaccinated, the survey found that the top three reasons for refusing a vaccine were the following:

191 students readily vaccinated in vacc-to-school program

By Ginuwine Kaye Bautista & Karl Aaron Galvez

Pili National High School (PNHS) conducted the PNHS Vacc-to-School Open Vaccination Program where a total of 191 individuals were vaccinatedandhavereceivedthe protection of the COVID-19 vaccines held on Thursday, January 12, 2023 at the school’s pavilion.

The program's primary goal is to provide students and