3 minute read

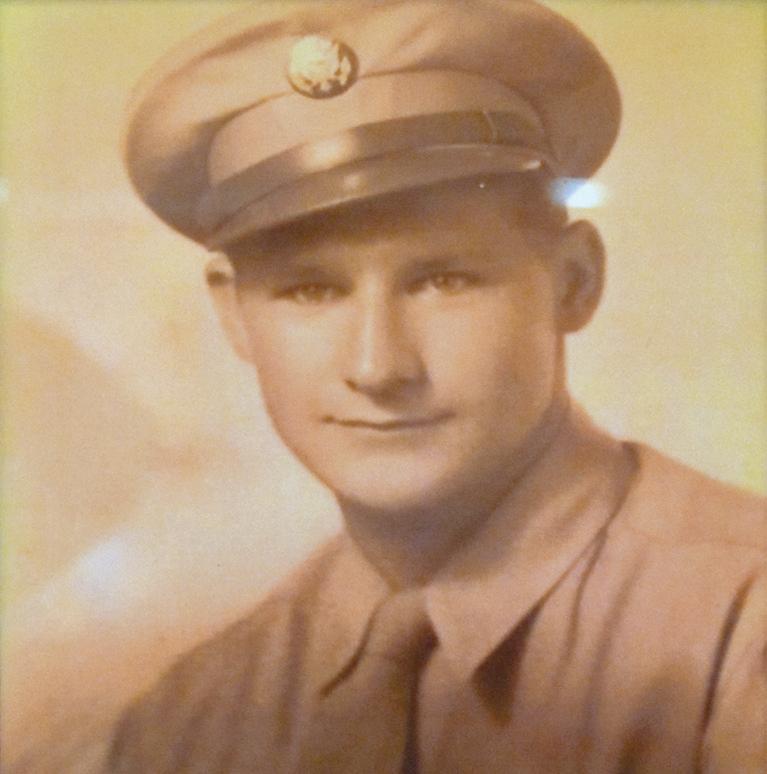

World War II veteran reflects on 100 years of life

On Dec. 10, 2022, Louis Horvath of Plymouth turned 100 years old. This is a remarkable feat in itself; however, before Horvath turned 25 he had already experienced the Great Depression and World War II firsthand.

Horvath grew up in South Bend, where his parents had emigrated from Yugoslavia. His father, who reached the US in 1912, made and repaired shoes, with storefronts in various locations, including the family home. He spoke little English, but, Horvath recalled, “He’d be working on his sewing machine and break a needle or something and say, ‘Damn the Bolsheviks!’ ”

The Horvath home was heated by a pot-bellied stove in the living room. Louis and his brother Pete shared a bed until the latter married.

Much of Horvath’s youth was spent out of doors, playing baseball, softball and horseshoes — “sandlot stuff,” he recalled.

“We were pretty primitive compared to today. There were no electronics in those days.”

That changed when the family acquired a crystal radio in the 1930s. Horvath was listening to that radio when Chicago Cubs’ player/manager Gabby Hartnett hit a walk-off home run in the ninth inning against the Pittsburgh Pirates as darkness was falling on Wrigley Field, just as the umpires were preparing to call the game. The “Homer in the Gloamin,” as it came to be called, helped the Cubs come from behind to win the National League pennant in 1938. He has been a Cubs fan ever since.

Horvath graduated from Central High School just before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and the US entered World War II. He was working for the Bendix Corporation as a shop clerk.

“I listened to the president’s speech on the radio that Sunday morning, the ‘day of infamy.’”

Horvath was drafted into the Army in 1942, and by 1943 he was training at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. He was initially assigned to an anti-aircraft battalion before transferring to the 11th Airborne Division. He qualified to be a paratrooper at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1945, but not before suffering serious whiplash on the last of five-straight days of jumps.

“I didn’t know I hit the ground. I was out. … But they woke me up … and I guess I was a paratrooper.”

Horvath got the news President Roosevelt had died from a farmer just after a practice jump. “That same day he died, they took us back to camp. We got cleaned up and stood honor guard for him.”

Roosevelt was staying at the “Little White House” near Fort Benning when he died, and Horvath stood at attention as his body was taken to the train station, accompanied by Eleanor Roosevelt and Chief of Staff George Marshall.

Horvath was deployed to the Phillipines in May 1945. He left from San Francisco on a large transport boat, and while there he ran into a friend from South Bend, a medic who was accompanying wounded soldiers. “He was coming up the stairs and I was going down. … We ran into each other that way, a thousand miles from home.”

As “primitive” as his upbringing in Depression-era South Bend was, Horvath still experienced culture shock in the Phillipines during the war. “You go back 100 years from what America looked like at that time and you get an idea of what it was like.”

Horvath emphasizes he was deployed as a replacement and “never saw serious combat.” However, he did make a combat jump to cut off the Japanese in northern Luzon. Landing in a rice paddy, he was one of several who were injured. “You had just as many guys get hurt on the jump as you do in combat,” he said with a chuckle.

While on this mission, Horvath learned the atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He felt relief, and for good reason. “They told us in training there would be 1 million casualties if we had to invade Japan. So we figure we’d never get out of that.”

He did go to Japan, but it was for the surrender. Horvath was part of the biggest movement by air ever attempted at that time. “They flew a whole division into

Japan on that surrender. When the surrender was signed, we were there.”

The remainder of Horvath’s time in Japan was spent “standing guard” in a rural area mostly populated by farmers. At one guard post he met a fellow Hoosier from Mishawaka. “A year later I saw him again. My sister married a guy in Mishawaka and this guy was there too. He worked with my sister’s husband. He was a paratrooper too.”

The second installment of this story will appear in the June 7 edition of The Shopping Guide News.