27 minute read

ON THE EDGE OF SOMETHING GREAT

Creating art that defies viewers’ expectations and traditions with modern forms of artistic expression is undoubtedly an accomplishment. However, contemporary Native American artists are taking it a step further. They’re fearless, in positions of disregarding any rules for their artistic style to portray their people in a current context, changing how the world perceives Native people. Here’s our list of cutting-edge contemporary Native American artists who all use their preferred mediums to incorporate culture, traditions, and storytelling into their art while addressing Native American social issues.

BY KELLY HOLMES

Advertisement

PLUS:

TATTOOS AS CULTURAL ART

Photo: courtesy

Chad Yellowjohn

At first, art was a way for Chad "Little Coyote" Yellowjohn (Shoshone-Bannock/Spokane) to express himself. "I was considered a mute, which means I didn't speak much," explains Yellowjohn. "When I spoke, it was jibberjabber." The positive reactions from family members seeing his drawings gave Yellowjohn the satisfaction needed to keep going. "I had a gift and wanted to spread that same joy to people." Raised near a small community called Usk, Washington, Yellowjohn quickly gained an interest in free-hand illustration, relaying ideas blossoming from imagination to paper. Now, Yellowjohn shows the world his art while sharing his story and spreading inspira- tion and awareness of the issues that Indig- enous people face in modern society. Today, he is motivated to promote optimistic activism and spread happiness through his art while incorporating laughter.

Please share with us a little bit about yourself.

I began drawing at the age of 2. My middle name and Indigenous name is "Little Coyote" (so don't be fooled, I am not a rapper though I've always wanted to produce one song). I've only completed two acrylic paintings in my life. I always had long hair. My favorite cartoon character is Goofy because he was a single dad who wanted to be a part of his son's life, and he's goofy. My favorite movie is Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and my dream is to make an animation where I'd be able to

converse with my own characters. I'm against Indigenous mascots, black lives do matter, womxn must be valued, and men are allowed to show emotion, all children must be saved including from the cages, I support my LGBTQ+ friends and the community, and I don't tolerate racism. I love to grass dance and dance to music, so if you ever see me busting out dance moves, I most likely learned it from my brother, Shanner. I love basketball, so if you see me being competitive and dribbling a basketball, I most likely got that from my brother, Ryan. If you ever see me in a magazine (such as this one), the credit most likely goes to my mom, my two brothers, and my family.

How has your upbringing shaped your identity? How did it shape your craft?

I was raised by my beautiful mother, Ione Yellowjohn, with my two older brothers Shanner Escalanti and Ryan Yellowjohn. My brothers are 10 and 12 years older than me, so it was hard to convince them to play ships with me, and I didn't have many friends in my part of the community to play with. I was considered a mute, which means I didn't speak much, and when I did speak, it was jibber-jabber. Whenever I finished a piece, I can remember the satisfaction and joy of making my brothers and mom smile. I had a gift and wanted to spread that same joy to people. When my brothers graduated and moved out of the house, I would have to tag along with my mother when she would paint buildings, clean houses, etc. If my mom wasn't cleaning homes, she was in her studio beading or sewing, which motivated me as a young artist. Wherever we would go, my mom would label me as her "little art-eest," and if I happen to be drawing at that very moment, she will reminisce about my art, which she still does today. My mother raised us boys as a single mother; she's worked too hard and risked a lot for me not to become somebody (which I'm still working at).

As a Native American artist, what point of view do you bring to your art? How does it set you apart from the rest?

Indigenous people have many traditions from many tribes. Coming down south to Santa Fe, New Mexico, I've got to experience cultures I didn't know exist. For me, it was hard to leave my community and family. Still, I felt responsible for sharing my experiences verbally and artistically as an explorer by sketching other peoples' cultures (with respect, of course). There is a beauty to every Indigenous culture, and I enjoy illustrating our traditional living. I am continually being inspired by art and artists, and I use that inspiration to make an impact on other Indigenous people to carry on further the culture we strive to keep alive. I honor my elders, ancestors, brothers, and sisters who dance, sing, pray, braid, and carry on those teachings by showing my appreciation through art. When I see an artist's creation, I'm looking at their perspective on how they see the world, making every artist unique. My unique way of contributing to the inspirational impact is I have always used markers. I started with Crayola markers, then Sharpies, and was blessed to stumble upon Copic markers. I'm very comfortable using a medium I've used my whole life; I struggle to switch mediums. However, using my precious markers, no mistakes can be made, and when they are made, there's no going back, nor is white-out the answer. Just like any obstacle we take on in life, I have to plan out every marking and take great care of how I approach it because what's done is done. However, mistakes will be made (created with markers), and it can't be fixed; the only way to make it for the better is to work with it. Which is what I do with markers; I work with the problem.

You spread awareness of issues Native people face as well as inspiration with your art. How do you incorporate activism into your art?

I consider myself a guy that doesn't like conflict. However, when I spread awareness, I'm letting the viewers know about how I (and others who have a similar mindset) feel about the issue, just like I would express to my mom how I feel through my art as a kid. Like many, I'm a big fan of Star Wars, and I know it isn't a surprise when I express that the Indigenous people can relate to the Rebels, or "scums" of the saga, an excellent comparison for non-Indigenous people to get a better understanding. I have to be triggered, and as a Sith, I use my anger while creating my pieces, which can be therapeutic for me. Otherwise, I'd be thinking about the issue non-stop. When creating an active piece, I feel a graphic piece needs to be illustrated; contrarily, my point will not be as strong. I struggled to create an active piece because I knew it would create conflict (which I was afraid of facing). Luckily I had a good friend who asked me, "Fine art pushes the boundaries if it doesn't stir up trouble or spark a controversial conversation, is it really fine art?" This led me to finish pieces such as "America's Great Again" (displaying an Indigenous man on a horse with storm troopers' [from Star Wars] helmets and Trump's head hanging on the side) and "Sorry Not Sorry" (displaying musical artist Childish Gambino [from the music video "This Is America"] taking a break behind an Indigenous womxn shooting Trump in the head, with Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson, and George Washington in line to be sentenced to death for all their sins against Indigenous People).

Since you use modern mediums such as markers, pens, and digital illustration, how do you balance these mediums while conveying the rich culture and history of the Native people who are in your work to the viewer?

Like every artist, art is a journey; it's a growing experience. Along the way, we pick up techniques and must drop the techniques that slow us down and learn how to balance them towards your objective as an artist. As mentioned, I started with Crayola markers; I would draw what I would see on TV, such as Bugs Bunny, and after continually drawing Bugs Bunny, I was inspired to draw my characters in that same style and as my tools transitioned to Copic markers; my sketches of Indigenous people progressed. As my hand drawing progresses, there's a technique within it that enhances my digital art pieces as well. There are differences: hand drawing is richer than the other because it's an original, digital is easier than the other because I can fix up any mistakes and put certain touches that I would struggle doing with by hand, just not as valuable. The similarity they both share is when they are set in my hands, as it will always portray my people's culture and the respect for another culture, my feelings upon is

Chad “Little Coyote” Yellowjohn. For more information about Yellowjohn and his art, visit his website WWW.LILCOYOTE.COM.

sues, and important elements of the culture.

Do you have a favorite work you most favor? Or has the utmost meaning to you?

My favorite art piece would have to be "Healing Echos," which displays nine Indigenous friends of mine, letting out their Warhoop/LiLi/Faumu. Colored with a warm grey for their skin tones, their mouths slightly exaggerated to give a powerful movement to their cries. If you saw me in action, you'd know I love to warhoop. I've expressed in my post about this piece that I enjoy the silence it creates and the echo that follows. I feel like the ancestors who once walked the land want the familiar calling they once let out at their lungs. When I traveled to Buckingham Palace in London, England, I let out my loudest warhoop, silencing that crowded area. I definitely informed the people of London that we are still here. With "Healing Echos," I hoped to have inspired Indigenous people to let out their Warhoop/LiLi/Faumu from time to time, not caring where they are and who is around. To me, it isn't just a cry; it's a healing cry that lets out my anger, my sadness; I use it for the joy I have for something and as a form of celebration.

How have you been dealing with and working during the COVID-19 pandemic?

This pandemic was a bummer. My artistic friends and I had an art show in Bristol, United Kingdom, called "Young Americans Exhibit" at the Rainmaker Gallery, which was canceled. I was also invited to London, United Kingdom, to perform, which was canceled as well. From the beginning of this pandemic, I drew up masked dancers, which displayed cultures dancing with masks. I intended for Indigenous people to keep their traditions alive during these isolating pandemic times. Due to the masked dancers, my publicity has increased. I had the honor to create a design for PowWows.com featured in the Great Lakes Pow-Wow Guide for the Anishinabek Nation. I illustrated for Supaman, my friend Nataanii Means, and I collaborated with First Citizen Co. and an Indian Relay Horse Race team.

J. NiCole Hatfield

A self-taught contemporary painter, J. NiCole Hatfield (Comanche/Kiowa), realized her love for drawing early. This love led to painting at the age of fifteen years of age. “Painting is medicine. It’s very healing to me,” Hatfield explains. Originally from Apache, Oklahoma, but now residing in Enid, Oklahoma, Hatfield is known for her paintings, which involve bright, attention-grabbing colors, while featuring Native people. Hatfield attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, for one semester, where she transcended her art into a range of different mediums. Her preferred medium is acrylic, which translates bold colors to canvas. “As a Numunu/Khoiye-Goo woman, there is nothing more important to me than the voice of my people,” says Hatfield. She draws her inspiration from historical photographs of her tribal people, particularly the women of the

J. NiCole Hatfield and her painting “Little Brother”. For more information about Hatfield, visit his website WWW. JNICOLEHATFIELD.COM. Photos: courtesy

tribes. “I want people to see the inner beauty and strength of our women, not just the physical appearance.” The vibrant colors represent her own emotions as well as the emotions that surround her. “We carry all of these beautiful colors within ourselves, and I want them to resonate with each portrait, without me having to speak about it.” Unity, spirituality, and connection to the Earth are at the center of her culture, and these are the teachings that Hatfield wants to continue to include in her art. “Storytelling is the way that we keep these traditions alive. I frequently incorporate tribal language and traditional stories into my paintings with the hope of inspiring the Native youth to keep creating and continue our traditions of storytelling in painting.” Hatfield’s artwork has been featured across the country, included painted across the sides of buildings as murals: in Anadarko, Oklahoma on the Lacey Pioneer Building, in downtown Oklahoma City on the E. Sheridan St. underpass titled “See The Woman,” and on the wall of the Thunderbird Casino outside of Norman, Oklahoma. Hatfield continues to participate in several Native American art markets throughout the year.

Where are you from? Tell us a little bit about yourself.

Haa Marawea Nu nahnia tsa Nahmi-A-Piah. My name is J. NiCole Hatfield Curtis, a self- taught artist and mother from Apache, Oklahoma.

How has your upbringing shaped your identity? How did it shape your craft?

I come from a long line of strong Comanche women; it has shaped me into a strong, resilient, independent woman. If I have my mind set on something, I go for it, and I don’t give up. That is what I did with art. It is apart of our tradition. I feel complete with art. It is medicine.

How did you get interested in painting, and how did you teach yourself?

It’s something that has always been with me. My family created in many art forms, whether that be beading, dressmaking, painting, etc. I have drawn since I could hold a pencil, but one day my high school art teacher gave me some paint and said, “Make me a masterpiece.” So I just dove in and never looked back. He allowed us the freedom to create and use what we wanted. This was during a dark time in my life; it was a way to express myself since I had a hard time doing that verbally. It was mentally and spiritually healing to me; it always will be.

As a Native American female, what point of view do you bring to painting? How does it set you apart from the rest?

Strength, leadership, balance.

What cultural values do you incorporate into your art?

I try to incorporate taking care of our elders and community, our children and women are sacred, equality, our beliefs, respect, and to always be giving, etc.

You include storytelling with your art. How do you come up with a story to tell within a piece/work?

The paintings I create have a story within the eyes, colors, and clothing. The story is your interpretation. Ledger pieces are my stories, things that I see, feel, and experience, I guess my own little diary.

How do you convey the rich culture and history of the Native person/people in your work to the viewer?

Through clothing, facial features, hair, traditional jewelry, and medicine paint.

Do you have a favorite piece/project/work you most favor? Or is it of the utmost meaning to you?

They all are, they are like my babies. A little piece of my spirit is in each piece.

You also mentioned inspiring Native Youth with your paintings frequently. Why is this important for you?

They are our future generation. They will be taking care of our people and traditions.

Mikayla Patton

Born and raised on the Pine Ridge reservation near the Black Hills of South Dakota, Oglala Lakota artist Mikayla Patton creates unique work using alternative printmaking methods, papermaking, and other mixed media, along with traditional beadwork techniques. Though Patton grew up without strong ties to the Lakota culture, she’s inspired to keep learning, in which she threads the Lakota stories and language she’s learned into her work. For example, Patton’s piece “Unci’s Love” is a three-piece addition to the relationship she remembers with her grandmas. Patton utilizes the process of papermaking to embed fabric and traditional medicines into a recycled paper pulp before its made. For Patton, the materials, textures, tears, and uneven edges of the paper embody many of healing actions. “On the surface, I have taken aspects of Lakota geometric symbolism to thread together personal and traditional forms,” she explains. “The paper is burned into, cut out, and embossed, and only a few possess color, but all reflect honest cultural importance.”

Please share with us a little bit about yourself.

I was born and raised on the Pine Ridge reservation. I left the rez to go to boarding school, then I went straight to college at the Institute of American Indian Arts but dropped out for a few years to raise money. Before returning to school, I had the opportunity to mentor a Lakota printmaker who taught me monotype printing and artist management. I continued my undergrad in 2015 and focused both on painting and printmaking. Towards the end of my undergrad, I decided to lean more towards printmaking and soon learned papermaking. I graduated from the Institute of American Indian Arts in 2019; I continue to work based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I am a printmaker/paper maker. I’ve been interested in paper sculpture, but I do work in various printmaking modes, incorporating beading, hand paper, etc.

How has your upbringing shaped your identity? How did it shape your craft?

I grew up in a family that didn’t have strong ties to my culture. I remember learning a few things from Lakota culture classes in the reservation school, but after middle school, I didn’t have a lot of Lakota-geared learning when I went to boarding school. Plus, when I was young, I was always afraid to ask for help or ask what this or that meant. But as I got older, I wanted to learn, and art helped me get through that. As an artist now, I’m continuously learning stories and language, which I thread into my work to understand and acknowledge what I’m learning. I never claim to know everything but rather get people to think about who my people are and how they empower me. My patience and life experiences shaped my work.

As a Native American artist, what point of view do you bring to your art? How does it set you apart from the rest?

The work I create is personal and explorative. I am a very emotional person and sensitive, but I find it necessary to express my thoughts and emotions through my work. I’ll be honest; I’m not great at sketching out what I want to make, but rather create through at the moment is my best trait. I wouldn’t say I’m very different from other Native Artists, I see us all working and expressing what we need to, and we must encourage each other.

How do you spread awareness of issues Native people face as well as inspiration with your art?

Well, I think the issue is that it is unfortunate that I am only learning my culture more as an adult, but it is inspiring that I’m doing it. I would want people and young natives to know that if they ever feel ashamed of not knowing that it’s okay to keep striving to overcome that feeling. This is a personal struggle but also a very common one among Native country.

You’re also known to use modern mediums such as papermaking and other mixed media and more traditional mediums such as beadwork techniques. How do you balance these mediums while conveying the rich culture and history of the Native person/people who are in your work to the viewer?

Native people have always been so innovative, and when we are introduced to new materials, there’s nothing we can’t do. At a young age, I remember beading before anything, but it wasn’t something I was the greatest at, and once I started printing and making paper, it was something I felt I needed to reintroduce myself to. I manage to incorporate beadwork into my current work because, as a Lakota person, it was my way of bringing and representing beauty and strength into my work. It’s not that I never saw my work in those ways, but it reaches something personal and cultural.

You also paint. What’s your preferred medium to create with?

Yes, in my undergrad, I focused a lot of my time painting, and I honestly thought I would continue to paint, but I found printmaking more artistically fulfilling. As a printmaker, I work in many processes, such as relief, intaglio, collagraph, and lithograph. Along with printmaking, I am also passionate about making my paper and beading. It seems like a lot to hand with different materials, but I find it rewarding for me. I have the beaver’s instinct to collect and find the right colors of beads, then I’m obsessed with textures from the paper, and printmaking in its own has so many modes of processes that I enjoy. I very much an artist who is it for the process and methods. Time and movement keep my mind at ease, plus a friend of mine told me Lakota women are always supported to be working on something. As an artist, it is a gift to see the world differently.

Do you have a favorite piece/project/work you most favor? Or has the utmost meaning to you?

Printmaking I love, but once I started making paper, I was happy to combine the two. Including beadwork, I am enjoying the work I’m doing now, but I think it’s because I’m in a place where I am creating work that fulfills my artistic abilities. My recent piece titled “Anpa Kazanzan Win,” is one of my favorite pieces so far. It is a paper sculpture made of my handmade paper, laser cutting, and sinew. The piece is a self-portrait reflecting stages of my life.

How have you been dealing with and working during the COVID-19 pandemic?

The early stage of the shutdown hit me pretty hard; I was financially struggling more than usual. Surprisingly before the pandemic, I applied for some residencies I wasn’t confident about and got a couple, the Dublin fellowship and the Roswell artist-in-residency. I’m used to working in a studio, but I had no choice but to work in my tiny apartment. I started beading more and eventually beading on my paper. That leads to some more ideas for future work. The pandemic also put some strains on my practice; I stayed mainly positive and stayed a lot closer to friends and family.

Mikayla Patton and her various works on paper and some beadwork she created. For more information about Patton and her art, visit her website WWW. MIKAYLAPATTON.COM. Photos: courtesy

Patton’s three piece edition, “Unci’s Love”. Photos: courtesy

Cara Romero

Cara Romero is a contemporary fine art photographer, producing stunning and expressive images of Native American people that tell uplifting stories of empowerment in a contemporary context: thriving, resilient, beautiful, and Indigenous. She’s deeply committed to doing work that addresses Native American social issues and changes how people perceive Native Americans, especially Native women, in contemporary society. “If we want respect, love, and beauty among us and others, we must actively promote it through art,” she says. Romero uses vibrant color, experimental lighting, and photo-illustration to explore ideas of how the supernatural world overlaps with our everyday lives. “In combining form and content, I reflect a uniquely Indigenous worldview that shows our thriving cultures’ resilience and beauty.” A citizen of the Chemehuevi Indian tribe, Romero was raised between contrasting settings: the rural Chemehuevi reservation in Mojave Desert, California, and the urban sprawl of Houston, Texas. Born in Inglewood, California, Romero’s family returned to the Chemehuevi Valley Indian reservation in 1979. Romero’s identity informs her photography, a blend of fine art and editorial photography, shaped by years of study and a visceral approach to representing Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural memory, collective history, and lived experiences from a Native American female perspective. Romero utilizes photography as her tool to resist Eurocentric narratives and as a means for opening audiences’ perspectives to the fascinating diversity of living Indigenous peoples. “My approach fuses time-honored and culturally-specific symbols with 21st-century ideas,” she explains. “This strategy reinforces the ways we exist as contemporary Native Americans, all the while affirming that Indigenous culture is continually evolving and imminently permanent.” Now married with three children (her husband is Diego Romero, a worldrenowned contemporary potter from Cochiti Pueblo raised in Berkeley, CA), she travels between Santa Fe and Chemehuevi Valley, where she maintains close ties to her tribal community and ancestral homelands.

Thank you for joining us. Please share with us a bit about yourself.

As an Indigenous photographer, I want to tell our own stories and express a different point of view through a medium that is used globally. Photography has become a universally shared way of visually communicating. I embrace photography as my tool to resist Eurocentric narratives and as a means for opening audiences’ perspectives to the fascinating diversity of living Indigenous peoples. My approach fuses time-honored and culturally specific symbols with 21st-century ideas. This strategy reinforces the ways we exist as contemporary Native Americans while affirming that Indigenous culture is continually evolving and imminently permanent.

How has your upbringing between the Chemehuevi reservation and Houston, TX, shaped your identity? How did it shape your craft?

These locations and experiences, urban and rural, my parents, Native American, and White, my individual experiences in each and both, are all just extremely different. Like two parallel universes, I think many of us Native folks have two traverses both worlds, and we learn to navigate and speak both languages. I try to be honest with those realities and share my truth. So, many of my images are autobiographical and often about my identity and the subjects’ identity. When I tell my truth, I think my artwork comes from the “space between,” which is like me—a collision of paradigms. I’ve always wanted to tell uplifting stories and stories that empower us. I always look around the world and media, and I want to see us next to all

Romero’s piece, “Revolver”.

the world cultures in a contemporary context, thriving, resilient, beautiful, Indigenous.

How did you get interested in photography? At what age?

As an undergraduate at the University of Houston, I pursued a degree in cultural anthropology. Disillusioned, however, by academic and media portrayals of Native Americans as bygone, I realized that making photographs could do more than anthropology did in words, which led to a shift in the study. I was 21 years old when I took my first black-and-white film class, and I had an amazing instructor, Bill Thomas, that emphasized content over technical ability. I fell in love instantly, and photography was a healthy compulsion that I always wanted to get better at while telling all the visual narratives I had racing around in my thoughts. I went to school at the University of Houston and IAIA for film and later to OSU for an Applied Science degree in Photography Technology, so digital and commercial became an important part of my practice. I love the medium and continue to learn and practice,

hoping to get even better.

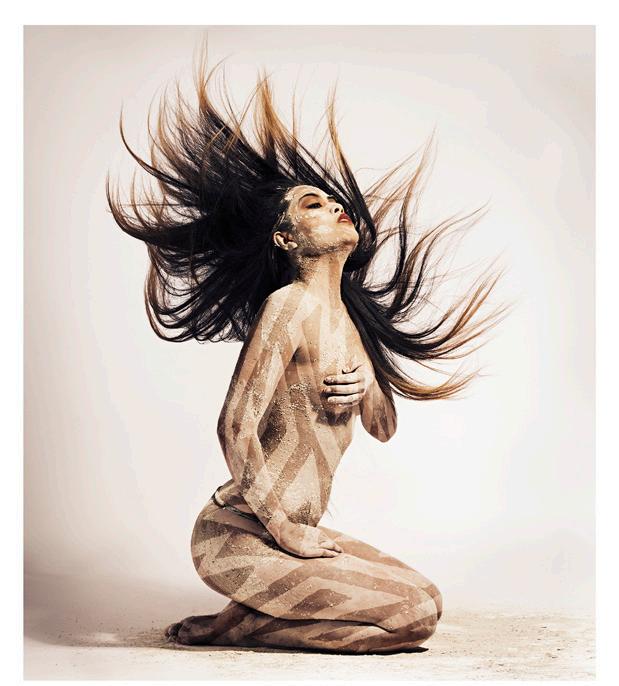

Romero’s piece, “Shameless”.

As a Native American female, what point of view do you bring to fine art photography? How does it set you apart from the rest?

The Chemehuevi people believe the Creator is a female deity, and the power of the female spirit is an integral part of our society. This sentiment resonates throughout my photographs, where strong female native figures take center stage. I believe it is a subtle but powerful shift to have a Native woman behind the camera in a traditionally white, male dominated-medium. I am deeply committed to doing work that addresses Native American social issues and changes how people perceive Native Americans, especially Native women, in contemporary society. If we want respect, love, and beauty among us and others, we must actively promote it through art. I am an empowered woman artist, and I am also a mother who must put my family first. As a Native woman, I have had to overcome vast challenges

to gain recognition from the art world and learn to invest in my practice. I want to prove that a young woman from a marginalized reservation can visualize Native people powerfully, give critical visibility to our communities, and represent a new era of national consciousness that elevates our youth and women.

You incorporate storytelling with your photography. How do you come up with a story to tell within your work?

My photographs explore our collective Native histories and how our indigeneity expresses itself in modern times. I firmly believe Native peoples are as Indigenous today as we were before the advent of colonialism. Sometimes I portray old stories, such as creation stories or animal stories, in a contemporary context to show that each grows and evolves with ensuing generations. I use vibrant color, experimental lighting, and photo-illustration to explore ideas of how the supernatural world overlaps with our everyday lives. In combining form and content, I reflect a uniquely Indigenous worldview that shows our thriving cultures’ resilience and beauty. Here, selfrepresentation through photography battles the “one-story” narrative that casts complex, living cultures into stereotypes, instead offering multi-layered visual architectures that invite viewers to abandon preconceived notions about Native art, culture, and peoples.

You’re also known to incorporate contemporary photography techniques with your storytelling while depicting the modernity of Native people. How do you do all this while conveying the rich culture and history of Native people in your work to the viewer?

Since 1998, my work has been informed by formal training in film, digital, fine art, and commercial photography. By staging theatrical compositions infused with dramatic color, I try to take on the role of storyteller, using contemporary photography techniques to depict Native peoples’ modernity, illuminating Indigenous worldviews, and aspects of supernaturalism in everyday life. When we as Native people explore new artistic tools and techniques, such as photography, we indigenize them. Our vision and an intimate relationship to our communities are precisely what make Native photographers the people best equipped to convey the allure, strength, and complexity of contemporary Native life. I am deeply committed to doing work that addresses Native American social issues and changes the way people perceive us in contemporary society. My style offers viewers sometimes serious and sometimes

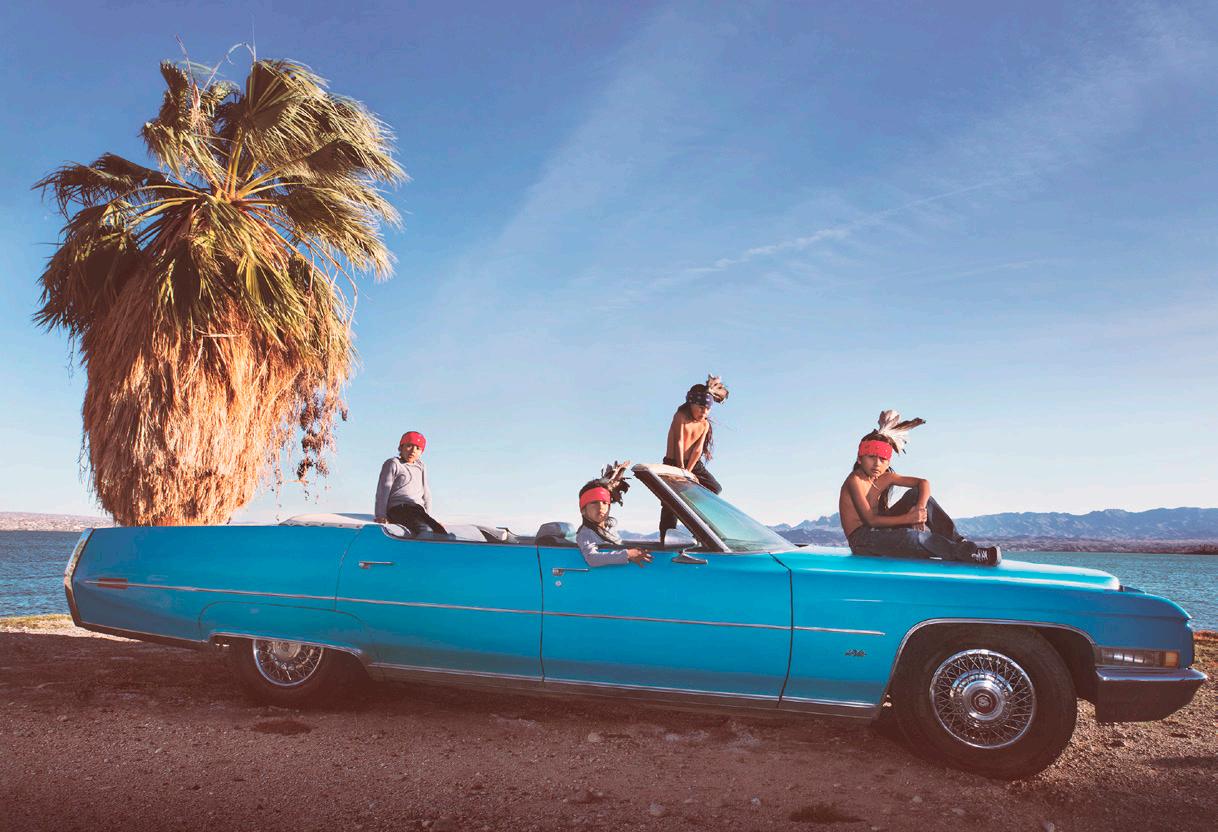

One of Romero’s favorite pieces, “TV Indians”.

playful social commentary on pressing issues like the border wall, the hypersexualization of Native women in histories of photography, environmental destruction of Native lands, and stereotypes of Indigeneity in pop culture. In response, I unapologetically depict where we are now, in the present day, making sure always to respect cultural protocol and ancestral ties. To further counter photography’s exploitive past, I actively collaborate with my models. Hailing from many tribal backgrounds and many geographic regions, these subjects are my friends and relatives. Together we stage photographs to tell stories that we feel (together) are important and give back to our Native community. My photographs explore our collective Native histories and how our indigeneity expresses itself in modern times. I firmly believe Native peoples are as Indigenous today as we were prior to the advent of colonialism.

Do you have favorite works you most favor? Or have of the utmost meaning to you?

“T.V. Indians,” “Water Memory,” “Last Indian Market,” “Kaa,” “Coyote Tales No. 1”, “Evolvers,” and “Puha,” to date.

How have you been dealing with and working during the COVID-19 pandemic?

I have been socially distancing and creating work with family confined to the outdoors and my Indian reservation for the last few months. Like many of us, our families’ and children’s’ mental health and well being have become my priority. I have been raising COVID19 relief funds for the Chemehuevi tribe’s youth through the Cultural Center and Education Departments. I hope to start a new series this month that will be released in the Summer of 2021.

For more information about Romero and her art, visit her website WWW. CARAROMEROPHOTOGRAPHY.COM.