7 minute read

Workplace Diversity: It’s More Than Meets the Eye

But I don’t have any diversity’ responded a colleague when I suggested he come with me to a recent conference session titled Diversity in Surgery. This common misunderstanding may underlie some of the difficulties with improving diversity, not just in surgery but in the whole profession of medicine.

Everyone has diversity. Yes, everyone. Two decades ago, when I was often ‘the only woman in the room’ in surgical teams, it was thought that just getting more women in the room would also ‘get’ diversity. As the numbers of women slowly increased, the same argument was applied to different groups- Indigenous people, those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, LGBTQI+, those from rural areas and so on.

Advertisement

There has been improvement in measurable characteristics, for example, the number of women surgeons in Australia has more than doubled, from 6% to 15%1, so men ‘only’ comprise 85% of active surgeons nowadays. However, the increase in raw numbers has not translated to leadership and academic roles, even though the first generations to benefit are now in their 50s and 60s2,3 This effect remains even in specialties such as anaesthesia (33% women), and obstetrics and gynaecology (gender parity achieved 2020)4,5

It is becoming clear that there is no ‘pipeline effect’. Simply getting more people with a specific characteristic is insufficient to create meaningful diversity 10 or 20 years later. There are deeper systemic influences which require a more nuanced understanding of diversity to effectively address.

Developing this understanding is worthwhile because the benefits of diversity are well known. Workforce diversity improves workplace cultures, improves organisational performance, and improves patient outcomes6. The Ottawa Consensus 2010 states that the medical workforce should be broadly representative of the population that they serve7, and it is known, for example, that the mortality penalty for black newborns cared for by black doctors is halved compared to white newborns8 and that women having acute myocardial infarctions have a higher survival when cared for by women doctors9. In Australia, lack of diversity similarly contributes to stubborn problems – rural areas underserved by doctors, a persistently high proportion of patient complaints relating to miscommunication, ingrained disrespectful workplace cultures arising from socialisation into ‘the’ (singular) culture of medicine.

At the same time, there is evidence that targeted programmes for diversity must be very carefully implemented to avoid unintended harms. My research published in the Lancet showed that ‘women in surgery’ programmes have contributed to women leaving surgical training through an ‘othering’ effect. The same research showed that many of the factors affecting women are common to all trainees, not just women10

It has been gratifying to see this research taken up by RACS, which has moved towards policies focused on common values such as respect, flexibility, and educational outcomes. This approach avoids implying that every member of a specific group requires special assistance based solely on a group characteristic, something known as a ‘deficit narrative’. The drawbacks of a deficit narrative become clear if you imagine the outcry that would arise if RACS set up a ‘men in surgery’ programme to give all men special support in view of their 10% lower pass rate in the general surgical Fellowship examination1. Equitable policies that apply to everyone, resulting in targeted support for individuals who require it – regardless of gender or any other characteristic – is more likely to achieve diversity than applying broad brushstrokes to entire groups defined by a nominal characteristic.

Everyone has diversity. Yes, everyone. To fully optimise the current and future medical workforce, we must understand two important concepts, intersectionality and equity.

Consider Figure 1. If a diversity committee were to choose the most diverse candidate for a position they would likely choose the Chinese woman (me), considering that the two men on the left were ‘lacking diversity’. However, it is likely that Philip Morris and I share more in common in terms of educational background and beliefs about equality than Kyle Sandilands in the centre, who is a shock jock well known for racist and sexist slurs on-air. This is the idea of thought diversity – that different ways of thinking contribute more to the benefits of diversity than visibly identifiable characteristics such as age, race, and gender.

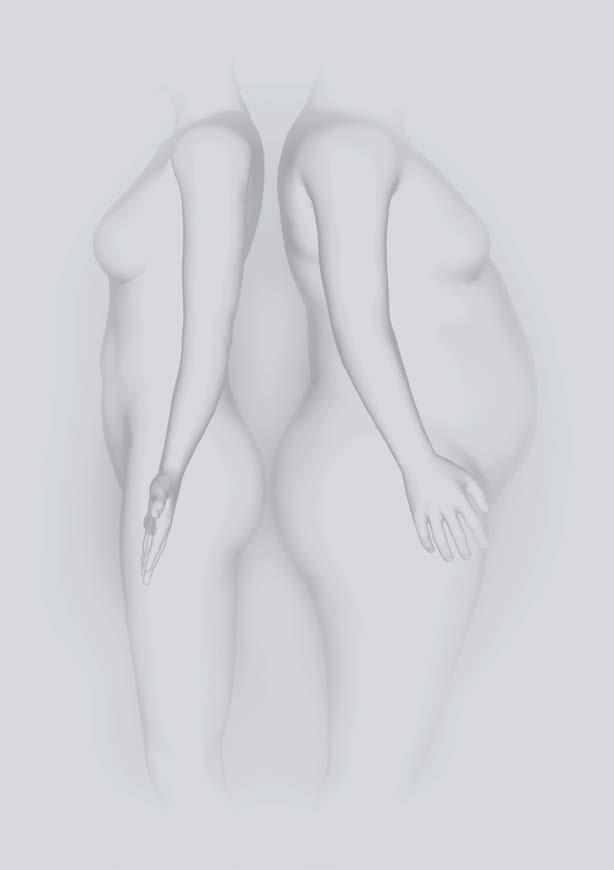

It may be noted that the language of ‘lacking diversity’ is a deficit narrative in itself. It does not make any more sense to say that someone is lacking diversity on the basis of being a man, than it did to say that women all required special assistance to be surgeons. A more contemporary view of diversity is shown in Figures 2 and 3. The Diversity Iceberg shows how people who look similar may in fact have very different backgrounds and ways of thinking, and that much diversity is invisible; ‘below the waterline’. The Intersectionality Wheel shows that there are characteristics that may be more privileging or oppressing in any given context. It is important to note that the composition of the wheel constantly changes depending on the situation. Having

English as a second language, for example, may be oppressing when trying to understand complex legal documents in English, but it may be a privilege when working as a medical translator. For any given time and situation, the ‘heat map’ will look different for individuals, each of whom sits at the intersection of all the many characteristics that make up who they are.

The concept of intersectionality is why claims that ‘we treat everyone the same’ cannot be sustained. We don’t, and nor should we, because to provide a level playing field we need equity, not equality. Unsure about the difference? Equality is treating everyone the same, which seems to make sense at face value but doesn’t bear logical scrutiny, because it merely reproduces existing privileges and oppressions. For example, if the aim is to select ‘the best’ for specialty training by awarding points for first-authored research publications, but some candidates live in metropolitan areas with much better access to research labs, are we selecting ‘the best’ in applying the same points system, or ‘the best located’?

Equity, on the other hand, is treating everyone towards the same common goal, and this is an actual levelling of existing privileges and oppressions to see who can then thrive when given the same opportunities. This may require some people to be given different resources to others. Figure 4 shows how, for a common goal of ‘riding a bicycle’, an equality approach means only one person achieves the goal, while an equity approach means everyone can achieve the goal by getting a different bicycle that suits them. Figure 5 is a humorous take on the same concept; many of us will remember some point in our medical training when we felt like the goldfish being asked to climb the tree. For me, it was being told as a fourth year student that I couldn’t scrub because my glove size wasn’t on the shelves, but I would still be expected to somehow demonstrate ‘gloving and gowning’ to pass the surgical rotation (an equality approach; everyone must be treated the same). Thank goodness I had excellent surgical mentors who perceived the difficulty and found ways to address it (an equity approach; different resources for different needs).

What, then, does this mean for efforts towards diversity going forward? Some practical suggestions:

1. Develop an equity approach. ‘I’m a good guy, I don’t see gender/race’ is an equality approach and continues the status quo; ‘I’m going to look for under-recognized good people and give them a hand’ is active mentorship based on an equity approach and leads to positive change.

2. Avoid making assumptions based on appearances. Broad statements such as ‘women tend to…’ or ‘you look like an orthopod’ ignore all the underwater parts of the Diversity Iceberg. By the same token, don’t accept disrespectful tropes such as ‘boomers’ or ‘dinosaurs’. Everyone has diversity. Yes, everyone!

3. Encourage thought diversity. We are not good at this in medicine. If a student or colleague offers a view that you disagree with, pause a little longer to consider whether it is wrong, or simply different. Wrong views should be appropriately addressed, but many things that were once considered ‘wrong’ in medicine (showing emotions in consultations, permitting trainees to take parental leave, being a doctor with visible tattoos) are now considered a normal part of our workforce diversity. It’s OK to disagree; it’s not OK to be disrespectful in expressing that disagreement.

As for my colleague who believed that he had no diversity? He came with me to the Diversity in Surgery session and was pleasantly surprised that it was not ‘just for women’ as he had feared. ‘I think I get it’, he said as we were exiting towards the exhibition hall for morning tea. ‘I was told I had to shave off my moustache for the Fellowship examination and I did it, even though I felt like a bald alien for the whole exam. My facial hair had nothing to do with my competence. I guess I need to stop putting the same illogical expectations on others?’

He had, indeed ‘got it’.

References

1. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, 2022. Activities Report 2021. Available at https://www.surgeons. org/-/media/Project/RACS/surgeons-org/files/reportsguidelines-publications/workforce-activities-censusreports/2021-12-31_RACS_ActivitiesReport_2021_V4_ Final.pdf?

2. Teede HJ. Advancing women in medical leadership. Medical Journal of Australia. 2019 Nov;211(9):392-4. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50287

3. Bismark M, Morris J, Thomas L, Loh E, Phelps G, Dickinson H. Reasons and remedies for underrepresentation of women in medical leadership roles: a qualitative study from Australia. BMJ open. 2015 Nov 1;5(11):e009384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009384

4. Bosco L, Lorello GR, Flexman AM, Hastie MJ. Women in anaesthesia: a scoping review. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020 Mar 1;124(3):e134-47. doi: 10.1016/j. bja.2019.12.021

5. Modra LJ, Austin DE, Yong SA, Chambers EJ, Jones D. Female representation at Australasian specialty conferences. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2016 Jun 6;204(10):385. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00097

6. Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2019 Aug 1;111(4):383-92. doi: 10.1016/j. jnma.2019.01.006

7. Prideaux D, Roberts C, Eva K, Centeno A, Mccrorie P, Mcmanus C, Patterson F, Powis D, Tekian A, Wilkinson D. Assessment for selection for the health care professions and specialty training: consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Medical teacher. 2011 Mar 1;33(3):215-23. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.551560

8. Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician–patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020 Sep 1;117(35):21194-200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913405117

9. Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient–physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018 Aug 21;115(34):8569-74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800097115

10. Liang R, Dornan T, Nestel D. Why do women leave surgical training? A qualitative and feminist study. The Lancet. 2019 Feb 9;393(10171):541-9. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(18)32612-6