8 minute read

Research & Technology pages 8 to

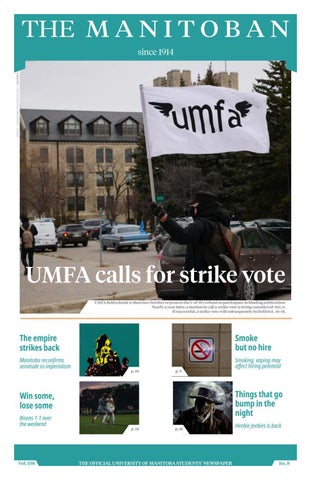

Stigma around smoking affects hiring potential

Anti-smoking and vaping stigma may prevent qualified applicants from being hired

RESEARCH & TECHNOLOGY

Emma Rempel, staff A study has demonstrated that the stigmatization of smoking and vaping can have negative effects in professional settings. Research published by Namita Bhatnagar, professor and F. Ross Johnson fellow at the Asper school of business, shows biased attitudes against smoking — and to a lesser extent vaping — persist in hiring decisions.

Bhatnagar and her co-author Nicolas Roulin, associate professor at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, N.S., published the smoking study in the international journal Human Relations.

Decades of negative marketing have contributed to reframing smoking as solely a public health issue. With her background in marketing, Bhatnagar wanted to explore whether this campaign has resulted in negative repercussions for individuals who smoke or vape.

Smoking and vaping was found to negatively bias the first impression of applicants in the eyes of interviewers. Troublingly, even a strong job interview was insufficient to counteract this negative first impression. Negative attitudes were found to be stronger toward smokers than vapers, indicating a stronger societal stigma against smoking.

To test Bhatnagar and Roulin’s hypothesis, they conducted mock job interviews. Participants in the study played the role of interviewers and rated actors portraying job applicants. Attitudes toward applicants who smoked or vaped were compared against a neutral behavior, like using a cellphone. The interviewers were allowed to select questions ranging in difficulty and were asked to assess the applicant’s responses.

In addition to participant ratings, the study assessed initial unconscious attitudes toward smoking applicants by using eye-tracking technology. This allowed researchers to determine that interviewers were fixated on smoking cues, indicative of negative attitudes toward smoking.

Bhatnagar recommended that students seeking employment be aware of their visibility as smokers, both in person and online. Social media posts can be screened during the hiring process, so applicants should exercise caution when posting on social media. Applicants should also be wary of smoking in highly visible public spaces designated for smoking, where an interviewer may spot them before an interview.

Additionally, the interviewer should undertake bias awareness training to encourage empathy. These courses could expand to include smoking and other stereotypical signifiers of lower economic status such as weight, tattoos, piercings and cannabis use.

“There’s no end to the traits that you can use to look down on people,” Bhatnagar said. It is not currently illegal in Canada to discriminate against smokers. It has been proposed that legal protections expand to protect smokers from discrimination, although there has been resistance.

“Legally, there’s a little bit of push and pull right now around smoking,”

— Namita Bhatnagar, professor in the Asper school of business

Bhatnagar said.

This places the responsibility on the individual applicant to be aware of potential anti-smoking biases.

Smokers themselves may be unaware of the extent to which this stigma touches aspects of their lives, including in a professional setting. Many current smokers may have retained the “glamorous” connotations around smoking that have persisted historically. It is this glamorized ideal that public health messaging has targeted.

Historically, shame and finger-wagging have been the go-to methods for public health messaging.

“Public health campaigns are designing messages to dissuade people from doing things that they deem as negative,” Bhatnagar said.

Bhatnagar acknowledged this campaign has successfully reduced smoking rates, particularly in youth and young adults. However, she worries whether the extent of stigmatization has resulted in negative outcomes that outweigh the benefits.

“On the one hand, it has lowered smoking rates, there’s no doubt about it,” Bhatnagar said.

“But on the other hand, it’s come at a cost.”

Some may see parallels in public attitudes toward individuals who choose not to vaccinate against COVID-19. Both are personal health-related decisions that can negatively impact and harm others. Bhatnagar wants to research more into effective strategies for communicating health messages without shame and stigma.

“I think the shame-based strategies, it alienates people that would have otherwise listened,” Bhatnagar said.

The challenge now facing Bhatnagar is to come up with effective marketing strategies to discourage smoking and vaping that do not result in stigmatization. Her research going forward will focus on changing perceptions on a variety of smoking products and the people who use them.

“How do you dissuade people from risky behaviors when you care about them?” Bhatnagar asked.

Marketing solutions could consider the social responsibility, acknowledging the harmful secondary effects of stigmatization.

“Marketing has created this monster,” Bhatnagar said.

It’s fitting that marketing can be a part of the solution.

Manitoba chose the crown over Indigenous people, again

A month after toppling colonial statues, Manitoba sent forces to Buckingham palace

COMMENT

Lucas Edmond , staff More than three months have passed since the toppling of the Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II statues at the legislative building. It has been reported that for the past two months, 90 soldiers from Manitoba have been training to serve the queen from Oct. 4 to 22. The timing cannot be a coincidence. It appears officials assume the public has forgotten the racist institutional response to the action Indigenous people took against the symbols of colonialism. But it also seems the government is prioritizing reconciliation with Queen Elizabeth II over the Indigenous people the statues offended. The famous self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” Audre Lorde once said, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” By this, Lorde meant the knowledge structures that facilitate systems of oppression must be dismantled before true liberation is possible for marginalized groups. Oppressors can never, and will never, become saviours.

Indigenous populations may find this quote resonates with them considering their long and difficult confrontation with colonial institutions — confrontations which are systemically organized to place them on the losing end of conflicts. In the process, they continue to lose their ancestral lands and rights.

Token actions of change have been made along the way in an attempt to scab an unhealing wound, but these performative gestures have mostly been institutional attempts to quiet the screams these wounds have produced. For the most part, hollow efforts by lawmakers, private interest groups, legislators and parliamentarians have been Band-Aids on shark bites.

For example, five years ago a group of activists noticed there was no tribute to First Nations people on the legislative grounds. Even the atrocities of the Holodomor are commemorated due to the large Ukrainian population residing in Winnipeg. However, none exist for the atrocities First Nations had to endure on the very land where the monolithic gears of colonialism continue to churn.

Last year, the province agreed to invest in a statue of Chief Peguis — the chief who played a crucial role in negotiating Treaty 1 and aided settlers on Indigenous land — by 2024. However, the statue had to share a public space with the statues of Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II. These two figures of the English monarchy visually memorialized perpetuators of genocide. For Indigenous people, the statues were more than just damaging symbology — they were an open embrace of settler colonialism and the collective trauma it caused.

As a result, on the momentous afternoon of July 1, 2021, Indigenous people gathered in outrage after the unearthing of mass graves found at various residential schools to express their indignation. The group proceeded to tear the colonial statues down. Many described the political demonstration as a collective moment of catharsis. Indigenous people took matters into their own hands, laid down the tools of their oppressor’s house and symbolically took the first step toward ripping the house down.

Settler institutions responded with rage. Then-premier Brian Pallister promised retribution. He then went on a racist tirade glorifying the history of colonialism which later culminated in his demise as the premier of Manitoba. British representatives also condemned the actions.

An excerpt from the famous social theorist Frantz Fanon’s seminal book The Wretched of the Earth best describes these colonial responses to Indigenous Manitobans’ social action.

“The settler makes history and is conscious of making it. And because [they] constantly refer to the history of [their] mother country, [they] clearly indicate that [they themselves are] the extension of that mother-country. Thus, the history which [they] write is not the history of the country which [they] plunder but the history of [their] own nation in regard to all that she skims off, all that she violates and starves,” he writes.

The constructed history Fanon refers to has clearly influenced the decision to extend a peace offering to the British crown. By sending Manitoban military forces to guard the figurehead of settler-colonial states around the world, Canada is revalidating its commitment to imperialism. This politically charged expression of solidarity should not fly under the radar. The timing is clearly correlated to the toppling of the statuary at the legislative building.

Dialogue surrounding the statues and this horrific history should remain open, but how long can Indigenous populations stand using the same tools that were used to construct their marginalization? How long until they are treated with respect?

The truth is, there is no perfect solution to reconciliation and decolonization. These decisions are, and should be, up to Indigenous populations. However, disassociation from the crown and colonial figureheads should be a minor first step. Putting the truth of genocide first, recognizing Canada and its various western institutions’ role in these injustices and extending uncontested self-determination to Indigenous populations is far more constructive than empty, white-led discourses about reconciliation. As activists shouted during the wresting of the statues, there is “no pride in genocide.” It is time to surrender the oppressor’s tools.