9 minute read

Feature

Martial arts groups grapple with pandemic realities

Instructors and organizers prepare to return this fall FEATURE

I had wanted to be some kind of martial arts master since the second grade. As soon as my family moved to the south end of Winnipeg, they found a guy who taught taekwondo classes out of the basement of the local community centre. Once I had a taste for it, my parents sent me to the Tae Ryong Park Academy to learn taekwondo.

By 2015, I had achieved my second-degree black belt and held a minor teaching post at the school. In the early years of my undergraduate degree at the U of M, I transitioned from taekwondo to Offenberger Muay Thai.

The last time I fought was in March 2020.

When the initial lockdown got called, it brought an end to 16 years of uninterrupted training. I did not know when I’d put on the gloves again. Worse still, if I got COVID-19 I might be among the one in three to suffer from long-term effects like debilitating fatigue, thereby putting my own body in the way of getting my training back on track.

Shortly before the start of the fall term, recreation services at the U of M announced that it would be resuming some of the pre-pandemic martial arts classes and clubs. My initial reaction was not charitable.

The idea of placing myself in a situation where I would be breathing heavily in close physical contact with strangers during a potential fourth wave of a deadly pandemic was not appealing.

Sparring, it seemed — especially for the grappling arts like judo and wrestling — would be extremely challenging to implement safely, especially considering they are high-contact sports and cannot be done from two metres away.

Given how niche the martial arts community is, I was not confident that the university had put sufficient thought into how to bring back these physically demanding classes and clubs safely.

I had concerns, so I raised them. I first reached out to director of recreation programs at the U of M Tanya Angus to get a handle on how the martial arts programs could be brought back safely.

“Everything’s a little bit different now than what it was prior to the pandemic,” Angus said.

“As of right now, the plan is that we’ll follow what they say in terms of the provincial guidelines and the restrictions that are in the return to play protocol and it will allow people to have contact.” controlling entrances and exits, staggering workout times, limiting capacity, maintaining two-metre spacing as much as possible, mandatory masks, double vaccinations and regular sanitization of hands and feet.

“One of the things that came forward in the return to play protocol for judo that we’re looking at for some of our martial arts programs is sanitizing their feet as well because there’s sometimes contact,” Angus explained.

“That was something that was a little bit new, but we want to make sure people are safe and if that’s what the suggested method is, then we’re going to continue to do that.”

The comprehensiveness of the restrictions and guidelines inspires confidence, and I can see aspects of my own practice adapting easily. Still, I wanted to reach out to the actual instructors to get their thoughts on how the restrictions would affect their styles.

Tim Manness has been involved the U of M’s wrestling club for the past decade and currently acts as a volunteer coach. While eager to get back to training, Manness is concerned about the club’s appeal given the restrictions.

“The current mandate of masks being worn at all times on campus will be very detrimental for our club,” he said.

“I don’t think many people are going to be interested in wearing a mask to wrestling. We’re hoping to keep the club running at whatever capacity we can until masks are no longer required and we can train normally.”

While some instructors like Manness predict there will be issues regarding the mandates, others are optimistic.

Horace Luong is a senior chemistry instructor at the U of M and an internationally recognized tai chi expert with 35 years of experience and proficiency in the chen, yang and sun styles. His tai chi classes are, in many ways, better suited to the restrictions than any other style.

“In terms of how the class would run, since it’s very solo […] I can walk around, do my corrections,” Luong explained.

“The students will have to participate with masks on, that’s something I’m not sure how people will take. We talk about inhaling, exhaling with movement and now you have something covering and that sort of disrupts that flow.”

Bryce Offenberger, a sessional instructor in the political studies department, is a former competitive fighter and has been running the Offenberger Muay Thai program at the U of M for the past 15 years. He broadly supports the measures, including the mask requirements.

“Naturally, we’re abiding by the protocols put in place by the government as instituted by the university,” Offenberger said.

“I know some gyms have come and gone with the mask requirement, but it’s not that hard of a thing and if it makes people feel safer, let alone if it does make people safer, then why not.”

Masks aside, the instructors’ enthusiasm to return is evident despite the restrictions, as is their passion to share the benefits of their style.

“You form a strong bond when you train hard with people,” Manness said.

“There’s a mutual respect that’s built. I’m always trying to make the club a fun place where people enjoy coming to each week, and where members are continually improving their skills.”

Luong, meanwhile, spoke at length about the personal development aspect of martial arts through the practice of tai chi.

“You’re […] not competing with anybody, you’re just doing it for yourself, and so there’s no need to worry about others,” he said.

Meanwhile, Offenberger sees his practice as a means to self-actualize.

“It’s this lifelong endeavour of incompleteness, essentially, that you just have to be comfortable with,” he said. “You can never master anything.”

“You have to find the inspiration to keep going on, and that, as you’re not maybe consciously aware of it, that’s that sort of journey of self-discovery.”

/ staff Dallin Chicoine / graphic

words / Liam Forrester/

staff

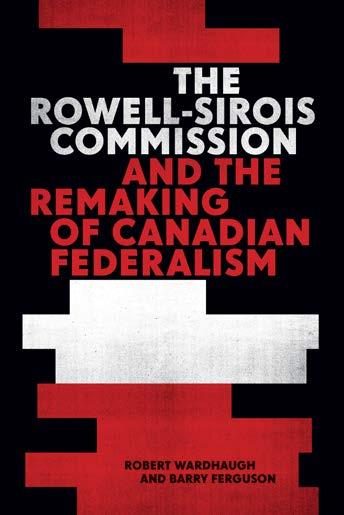

Retired prof authors Roswell-Sirois Commission book

Analysis of commission illustrates where we have been and where we may return

RESEARCH & TECHNOLOGY

Michael Campbell, staff Barry Ferguson, a retired professor from the department of history, has recently copublished The Rowell-Sirois Commission and the Remaking of Canadian Federalism alongside Robert Wardhaugh of Western University. The book was published by the University of British Columbia Press as part of the C.D. Howe Series in Canadian Political History, which encourages fresh perspectives and novel analyses on all aspects of Canadian policy and history.

Ferguson was also appointed the Duff Roblin professor of government in 2014, a position which allowed him to conduct research and teach within the department of political studies. The position also allowed Ferguson to hire students to help him complete his research for the book.

“Political science students really love politics,” Ferguson said.

“And they like political ideas, they like the nitty gritty of institutions. And so it was really a treat to teach them during the last six years of my work life.”

Ferguson and Wardhaugh’s book aims to provide readers insight into how the commission shaped Canada. The commission emerged in a time of great difficulty and petitioned the federal government to improve the quality of life for Canadians.

The Rowell-Sirois Commission, officially known as the Royal Commission on Dominion–Provincial Relations, examined the depressed Canadian economy of the 1930s and ’40s and how social and financial obligations were split between the provincial governments and federal government. The common name comes from the surnames of its two chairs, Newton Rowell and Joseph Sirois.

Ferguson explained the Canadian federal system had been effectively broken by the Great Depression.

“And what that means is the federal and provincial governments could not cooperate on measures to deal with the economic and social crisis,” Ferguson said.

“In the case of the Prairie provinces, the economic problems were actually catastrophic, so that Saskatchewan and Manitoba were — as much as the government ever could be — bankrupt […] So, there was a problem of regional crisis that was pretty serious. So, the royal commission, you know, had to deal with the fact that the federal system in Canada was an utter mess and nobody could figure out how to get out of it.”

The problem underlying the Great Depression in Canada was that the federal government had the funds to bail out the provinces, but it did not have the constitutional authority to take the reins. Per the British North America Act, the federal government was responsible for taxation of all Canadians, and the provinces could only tax their own residents and only for specific purposes.

The result was that the federal government raised significantly more money in taxes than the provinces were able to, but the provinces were responsible for the services we have come to think of as funded by taxes, such as hospitals, roads and schools.

“When you pay your taxes […] the income tax money is collected by the federal government and then doled out to the provinces. That’s what the royal commission said should be done,” Ferguson said.

However, at the time there was no agreed-upon method to transfer large sums of money from the federal government to the provinces.

“The Dominion government, as they call it — the federal government — has the money [but] it has got to share it equitably,” Ferguson said.

“[Prime Minister] R. B. Bennett rants and raves and gives a lecture to John Bracken, the premier of Manitoba, and says ‘Well, I’ll give you $20 million, but you better be a lot more responsible.’”

These financial bailouts came haphazardly, and only when the provinces were in dire circumstances. The federal government was unable to dictate what the funds were to be used for, so instead, they came with heavy political posturing. Although transfer payments existed since Confederation, the formal system of equalization payments was not adopted until 1957.

Ferguson and Wardhaugh’s analysis of the commission illustrates how the commission was prescient on other matters as well. In 1940, the commission argued that the federal government should implement and provide money toward medical care and provided a structural framework for further commissions.

“It was the first big [royal commission] and basically the archetype [for] modern royal commissions,” Ferguson said.

According to Ferguson, the Rowell-Sirois commission was the biggest and most influential royal commission until the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and its successor the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The Rowell-Sirois Commission, by virtue

— Barry Ferguson, retired professor

provided / Barry Ferguson image /

of its contributions to institutions which we recognize as fundamentally Canadian, had an enormous impact on our fledgling nation.

Ferguson and Wardhaugh’s new book may provide insight into the next chapters of Canadian history being forged during our current economic downturn.

“I do wonder about the long-term consequences of the massive deficit financing that the federal government and the provinces are engaged in,” Ferguson said.

“The big thing that I worry about [that] nobody cares about, except maybe the one writer in current politics […] Andrew Coyne of the Globe and Mail is saying, you know, there’s an awful lot of federal government activity and they’re not listening that closely to the provinces.

“And that’s exactly the kind of situation that had existed in the 1930s.”