35 minute read

KIBBUTZ DOWN UNDER

AROUND THE COMMUNITY

NOMI KALMANN COURTESY: TABLET MAGAZINE

Australia’s Hachshara (Hebrew Training Farm) prepared a generation of young Zionists for life in Israel

The kibbutz movement was founded in 1909. It combined Europe’s growing socialist movement with the new and exciting ideology of Zionism, billing itself as a new way of Jewish living. The movement spread like wildfire, with thousands of young people from around the world moving to British mandated Palestine to create kibbutzim, where they pooled their resources to overcome the hurdles facing new agricultural towns in the future Jewish homeland.

Meanwhile, halfway across the world, a copycat community was created to foster Zionist spirit among young Jews and encourage immigration to Israel.

From 1945-67 an Australian kibbutz – officially known as the “Hebrew Training Farm”, but more commonly referred to as “Hachshara” – was in operation. Located in Toolamba, a small farming community about 160 kilometres north of Melbourne, the kibbutz was owned by the Zionist Federation of Australia and was operated by idealistic Jewish youth movement leaders from the Australian branches of Habonim and Hashomer HaTzair.

On Hachshara, young Aussies spent a year or two learning Hebrew and agricultural skills with the aim of inspiring Zionists to take the plunge and move to Israel.

“My father, Aharon Kaploun, had an orchard in Toolamba; he sold it to the Hachshara in 1945. It had pears, peaches, apricots and plums, and a horse called Sandy,” recalls Aviva Oberman, an 87-year-old Australian Israeli who now lives in the Jerusalem Hills. “I was a kid then, maybe 12 or 13 years of age, and Toolamba was this little township of orchards. After he sold the orchard, my father stayed on for a few years … to teach the [participants] agricultural skills.”

For 22 years, this orchard and property would serve as the pinnacle of Zionist activity among Australians and New Zealanders, the vast majority of whom ended up settling in the new State of Israel.

Selina and Jack Beris, an Australian Israeli couple married for 62 years and now in their 80s, were both members of the Habonim youth movement in Australia. After spending time on Hachshara, they moved to Israel in 1961.

Joining a group of 17 Aussies, all members of Habonim, Selina arrived on Hachshara in 1957; Jack arrived 12 months later.

“We used to get up at about 6:30 in the morning. We had Ivrit [Hebrew] lessons – not that they did me much good – and, after, we would go to work in the orchards, picking fruit,” she said. “We also had cows and chickens. Later, the group would have lunch and dinner together.”

The conditions on the kibbutz were poor, with fibro sleeping huts and outdoor sheds for showering. Despite these tough conditions, the months spent on Hachshara were great fun and many of the original crew that Selina and Jack met there remain lifelong friends.

“When we went on Hachshara in Toolamba, we were innocent young Zionists. We were totally absorbed in learning about how to build up the state of Israel,” Selina said. “Even though some [of the original Hachshara immigrants] went back to Australia, a lot are still here in Israel and whoever is here, we still get on really well.”

Josie Lacey, an 87-year-old Sydney resident remembers visiting the Hachshara, along with a small group of friends, over the Australian summer about 70 years ago. She was a member of Habonim. “We were there to do fruitpicking,” she said. “I remember picking the apricots off the trees. It was rather exciting to be there, playing kibbutz.”

Lacey did not end up making aliyah, but many of her friends who spent a year or two at Hachshara did move to Israel. “They were amazing people, the ones who went,” she said.

Though it may seem unusual that a kibbutz to train and prepare youngsters to move to Israel was established in Australia, Lacey thinks that it reflected the time. “In those days we did strange things to prepare ourselves for aliyah,” she said. “In Habonim, we would use a rope to cross a gully with heavy backpacks to prepare ourselves.”

While many Hachshara participants learned orcharding skills, these were not particularly useful in Israel, where similar types of stone fruit trees do not grow. However, as the overarching purpose of Hachshara was to prepare Australians for life in Israel, the fact they were learning skills that were not necessarily directly transferable were inconsequential to fostering their Zionist spirit.

Throughout the period Hachshara existed, some of the best and brightest Jewish Australians spent time there.

Jack Cohen was in the final group of young Aussies at Hachshara from 196566. A technician by training, he undertook various roles including works manager, treasurer and maintenance, as well as cooking. “In the 1960s, for people living in Australia, leaving home and living 160 kilometres from Melbourne, in very poor conditions, that was one of the purposes of the kibbutz,” he said. “We learned how to live communally and the poor conditions prepared many of us for the conditions we met when we moved to the new State of Israel.”

Cohen believes that Hachshara finally closed in 1967 due to a confluence of factors. “Over the time it operated, the Hachshara could never make a profit, so essentially it imploded financially,” he said. “The Zionist Federation of Australia was eager to sell it.”

Another challenge that contributed to its demise was a shift in Australian government policy in the 1960s, which made university free for all students. “Most of my friends who would have come to Hachshara took advantage of this and went on to university to study and become doctors and lawyers, because the degree was free,” Cohen said.

Jeremy Leibler, the current head of the Zionist Federation of Australia, reflected on the importance of Hachshara in Australia. “Over many decades, the Zionist youth movements in Australia have used immersive, group experiences to develop knowledge, leadership skills and commitment to Israel and the Jewish community,” he said. “As international travel became more accessible, this local Hachshara program was replaced with shnat [yearlong] programs in Israel. Generations of youth leaders have participated … as current youth movement leaders still do.”

Despite the closure of Hachshara in 1967, Habonim remains a popular choice for young Jewish Australians, with Gabriel Freund, the current federal mekasher of Habonim Dror Australia noting that it is the largest non religious Jewish youth movement in Australia. Freund reflected on the history of Habonim’s involvement in Hachshara with a sense of pride: “The Kibbutz Hachshara is one of the proudest chapters in Habonim Dror Australia’s history. The stories of those pioneering members who attended Hachshara and went on to make aliyah and live on kibbutz in Israel continue to inspire new generations of Habonim members today.”

Jack Cohen made aliyah shortly after he finished up on Hachshara. He and his wife both lived in Israel for 50 years, before returning to Australia around eight years ago, after one of their Israeliborn daughters decided to emigrate back. In 2009, he took a group of current Habonim leaders to Toolamba to see the original property that housed the Hachshara kibbutz. The fibro huts that the participants used to sleep in were still standing, although the property had long been sold to new, non-Jewish owners.

Despite being one of the last participants on the Australian Hachshara Kibbutz, Cohen reflects fondly of his time there. “Going to Hachshara broke the mould of how you lived in Australia,” he said. “It was great, and it was definitely character building!”

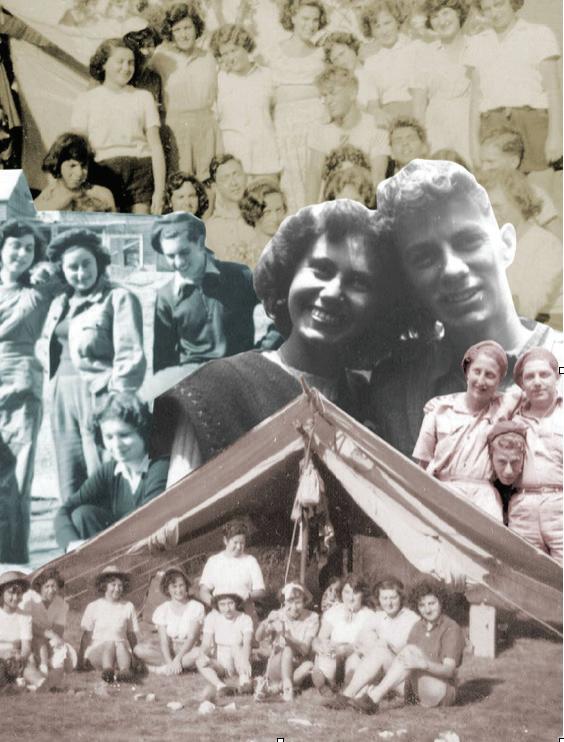

The kibbutz down under

Habonim camps in Melbourne and Sydney in the late 1940s (photos courtesy Elie Lederman via Facebook)

JUDAICA QUIZ

RABBI DAVID FREEDMAN

When we think about the festival of Shavuot, we think about the giving of the Torah; we think about the Divine covenant between G-d and Israel at Mount Sinai. We also think about the wisdom garnered within the Book of Ruth and we can’t help but think about the delectable dairy delights that await. It truly is a joyous time.

Rabbi Freedman’s sensational Shavuot quiz explores all this and so much more. Make sure you save this to enjoy with family and friends at your Yom Tov table. It has been cleverly crafted just for you! 1. Why is the festival of Shavuot given this name? 2. Which Shavuot custom is associated with Exodus 34:3: “No one is to come with you or be seen anywhere on the mountain (Mt. Sinai): not even the flocks and herds may graze in front of the mountain”? 3. Complete this name for Shavuot: Zeman Matan … (The Season of Giving …).

4. By what other name is Mt. Sinai known as in the Bible? 5. What blessing is recited each night between Pesach and Shavuot? 6. Which Shavuot custom is associated with these words from Isaiah 50:2: “When I came, why was there no one? When I called, why was there no one to answer?”

7. The Book of Ruth, read on Shavuot, is connected with which annual grain harvest? 8. Many opt to stand when the Ten Commandments are recited publicly in synagogue. This is not a universal custom – why do some Jews choose to remain seated? 9. In the Book of Ruth read on Shavuot, what was the name of Ruth’s mother-inlaw? 10. Which Hebrew word is the most common word in the Ten Commandments? How many times is it found? 11. Why do Jews have a tradition to eat cheesecake on Shavuot? 12. True or false - another name for Shavuot is “Atzeret” indicating it is the Concluding Festival? 13. Yetziv Pitgam is a poem that precedes the reading of the Prophetical

reading (the Haftarah) on which day of Shavuot in the Diaspora? 14. Is Akdamut: a) a special Shavuot Cheese Blintz that originated in Iraq b) the name of the ritual connected to the offering of the First Fruits brought on Shavuot c) a liturgical poem recited annually on Shavuot? 15 Name the monastery that lies at the mouth of the gorge, located at the foot of Mount Sinai.

16. Film producer Cecil B. DeMille made two versions of the movie: The Ten Commandments – in which two years were they each released? 17. What are the following with the Yiddish names: ‘shevuoslach’ (also known as ‘shavuosl’) and ‘royzalach’ (also known as ‘raizelach’)? 18. Boaz and Ruth are a pair of paintings by Rembrandt dated 1643. According to art scholars, who is said to represent Boaz and Ruth in these paintings? 19. Shavuot occurs in the month of Sivan – what is its corresponding Zodiac sign? 20. In which book of the Bible is the actual name Sivan first mentioned? 21. What is the next festival in the Jewish calendar following Shavuot? 22. Which famous rabbi first came to the United States of America in the month of Sivan in 1941? 23. What was the relationship between Ruth and King David? 24. How many times does the name David occur in the Book of Ruth: a) once b) twice c) three times? 25. On the annual calendar, when was King David born and when did he die?

Test your knowledge

Good luck. Enjoy. Hopefully, learn something new about your Jewish heritage and tradition.

ANSWERS PAGE 12

YOUR GIFT TODAY WILL BE MATCHED DOLLAR FOR DOLLAR! PLEASE HELP US STAMP OUT RACISM, BULLYING & PREJUDICE

DONATE ONLINE AT: COURAGETOCARE.ORG.AU OR SCAN THE QR CODE

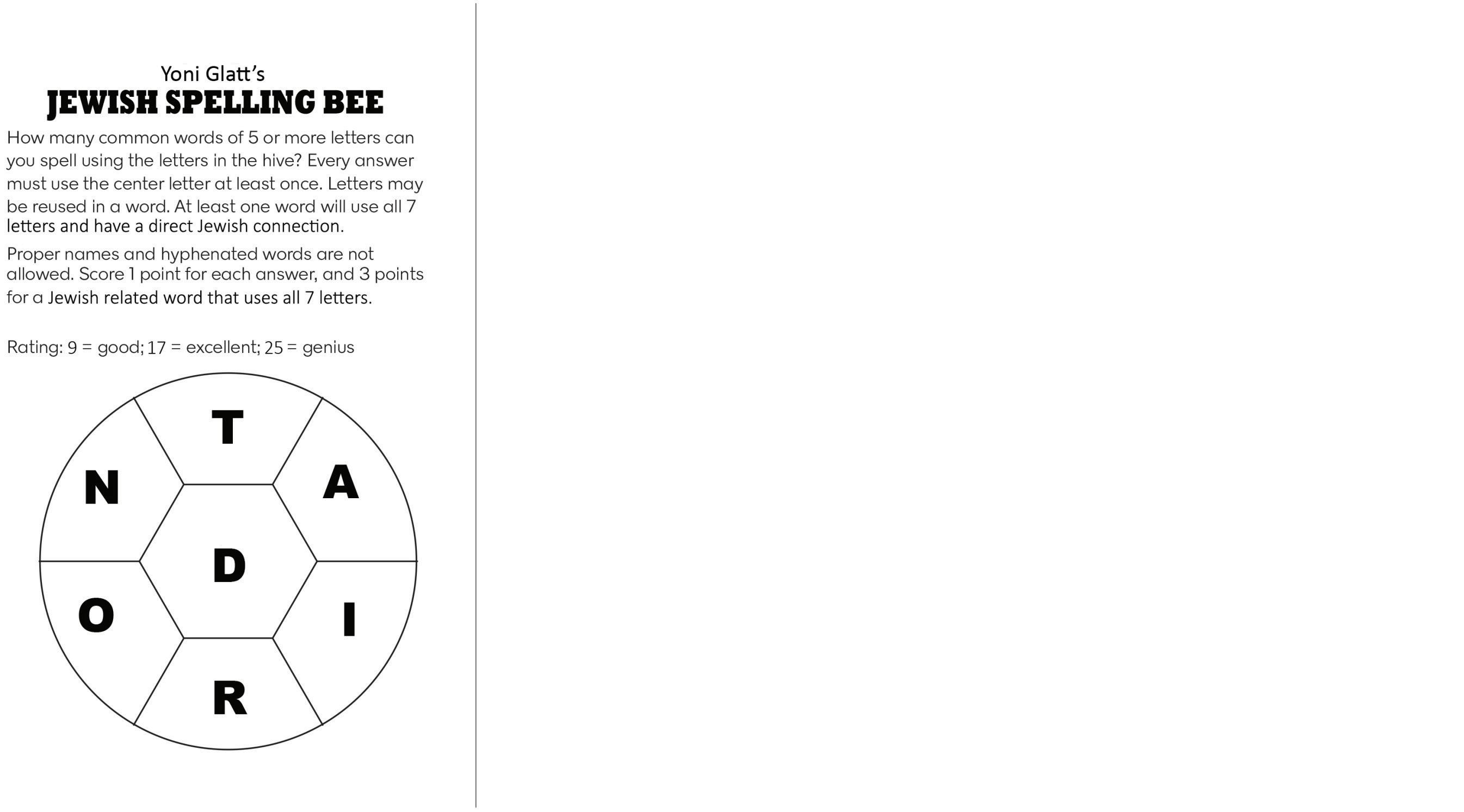

Yoni Glatt’s JEWISH SPELLING BEE

How many common words of five or more letters can How many common words of 5 or more letters can you spell using the letters in the hive? Every answer you spell using the letters in the hive? Every answe must use the centre letter at least once. r must use the center letter at least once. Letters may Letters may be reused in a word. At least one Jewish word will use all seven letters. be reused in a word. At least one word will use all 7 letters and have a direct Jewish connection. Proper names and hyphenated words are not allowed. Score one point for each answer and three points for a Proper names and hyphenated words are not allowed. Jewish-related word that uses all seven letters. Score 1 point for each answer, and 3 points for Rating: 28=Good; 34= Excellent; 40= Genius a Jewish related word that uses all 7 letters. Rating: 9=Good; 17= Excellent; 25= Genius Yoni Glatt has published more than 1,000 crossword puzzles worldwide, from the LA Times and Boston Globe to The Jerusalem Post. He has also published two Jewish puzzle books: "Kosher Crosswords" and the sequel "More Kosher Crosswords and Word Games". Here is a list of some common words (Yes, we know there are more words in the dictionary that can work, but these words are the most common):

FOODIES'

CORNER Who doesn’t like cheese?

YANKEL WAJSBORT KOSHER AUSTRALIA

Kosher Cheese?

One of the most well-known customs on Shavuot is to have cheesecakes and cheese products.

Ta’amei Minhagim (written by Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Sperling, published in 1890) explains that one of the names that Mount Sinai is known by is “Har Gavnunim” which bears a similarity to the Hebrew word Gevina, which means cheese.

Here are some interesting cheese facts:

Legend has it that the first cheese was discovered in the Middle East when milk was stored in skin flasks made from the stomachs of cows.

The first production line cheese factory was set up in Switzerland in 1815.

The US produces 29 per cent of the world’s cheese.

In the United Kingdom alone, 700 different types of cheese are produced.

There are nearing 2,000 varieties worldwide.

Among the highest consuming cheese nations are France, Iceland, Finland, Denmark and Germany.

The Guardian newspaper claims cheese is one of the most shoplifted items from supermarkets globally.

How is cheese made?

Usually cheese is produced by acidifying (souring) milk and adding rennet. The acidification is accomplished in a few cases by the addition of an acid-like vinegar (paneer, queso fresco), but usually starter bacteria are employed. These starter bacteria convert milk sugars into lactic acid. The same bacteria (and the enzymes they produce) also play a large role in the eventual flavour of aged cheeses. Most cheeses are made with starter bacteria from the Lactococci, Lactobacilli or Streptococci families. Swiss starter cultures also include Propionibacter shermani, which produces carbon dioxide gas bubbles during aging, giving Swiss cheese or Emmental their holes.

Some fresh cheeses are curdled only by acidity, but most cheeses also use rennet. Rennet sets the cheese into a strong and rubbery gel, compared to the fragile curds produced by acidic coagulation alone. It also allows curdling at a lower acidity, which is important because flavour-making bacteria are inhibited in high-acidity environments. In general, softer, smaller, fresher cheeses are curdled with a greater proportion of acid to rennet than harder, larger, longer-aged varieties.

At this point, some cheeses are ready – they are drained of excess whey, pressed and packed. Some hard cheeses are heated to force out more whey. Salt can be added for flavour and as a preservative. Sometimes the cheese is stretched (e.g. mozzarella), washed in water or wine (edam, gouda or Colby) or cheddared (chopped up while liquid). Aging allows different enzymes to come into play altering the taste further. Pungent cheeses, such as Lindberg, are realised by allowing spoilage to take place.

Kosher requirements

The rabbis in the Talmud (Avodah Zarah 29b) cited up to eight different reasons why cheese produced by a nonJew (“Gevinas Nochri”) is prohibited. The most commonly accepted reason is that rennet from a non-Kosher slaughtered animal was usually used for the curdling process. As the rennet is a Davar HaMa’amid (something that preserves or drives the process), the rennet is significant, even though its percentage is small.

Due to the difficulty in verifying the kosher status of the rennet and the likelihood that the source was not kosher, the rabbis of the time prohibited all hard cheeses from being given kosher status. The only allowances where when either a Jew placed the rennet into the milk or the milk was owned by a Jew.

As animal rennet is rarely used today (except for export to the Japanese market) and cheese production is usually controlled by microbial or vegetarian rennets, the prohibition remains in place.

Recent distinctions were made between those cheeses that require rennet (“rennet-set cheeses”) and those that are softer and utilise acids (“acid set cheeses”). While rennet-set cheeses are prohibited, acid-set cheeses (e.g. cottage and cream cheese) are permitted, even if they do use rennet.

Vegan cheeses

While on the topic of cheeses, we are frequently asked about vegan cheeses.

Vegan cheeses are made from various nuts, such as cashews or macadamias, or from other plant-based materials such as coconut milk.

Other ingredients typically used are food gums, such as agar, carrageenan or xanthan gum, as well as tapioca, lemon juice and flavours to simulate regular cheese. Probiotic cultures are often used.

An interesting point for discussion is whether vegan cheese can be actually be called cheese. For example, the European Union only allows “cheese” to be used when referring to dairy varieties.

Vegan cheeses are not subject to the same rules of kosher dairy cheese production, but are governed by regular kosher rules as a number of the ingredients are kosher sensitive.

12,000 products Traveller’s Guide Bug Checking … and more

The 2022 Kosher Food Guide is now out.

To obtain your free copy call 1300KOSHER or email info@kosher.org.au Also get free access to the Kosher App

CONSIDERED OPINION

RABBI MORDECHAI BECHER COURTESY: AISH.COM

I am not sure what Socrates would have made of the internet and social media, but in one of the dialogues recorded by Plato, Socrates criticises the art of writing as something that would destroy memory. “This invention of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember by themselves …”1

To some extent Jewish tradition agrees and this is one reason that for over 1,500 years most of Judaism was transmitted in an oral format, known as the Oral Torah.2 Eventually it became clear that due to the circumstances of exile, unless this information was committed to writing it would be lost completely. In about 170 CE Judah the Prince, a Rabbi and leader of the Jewish people, decided to write down the oral information in the form of a six-volume work known as the Mishnah.3

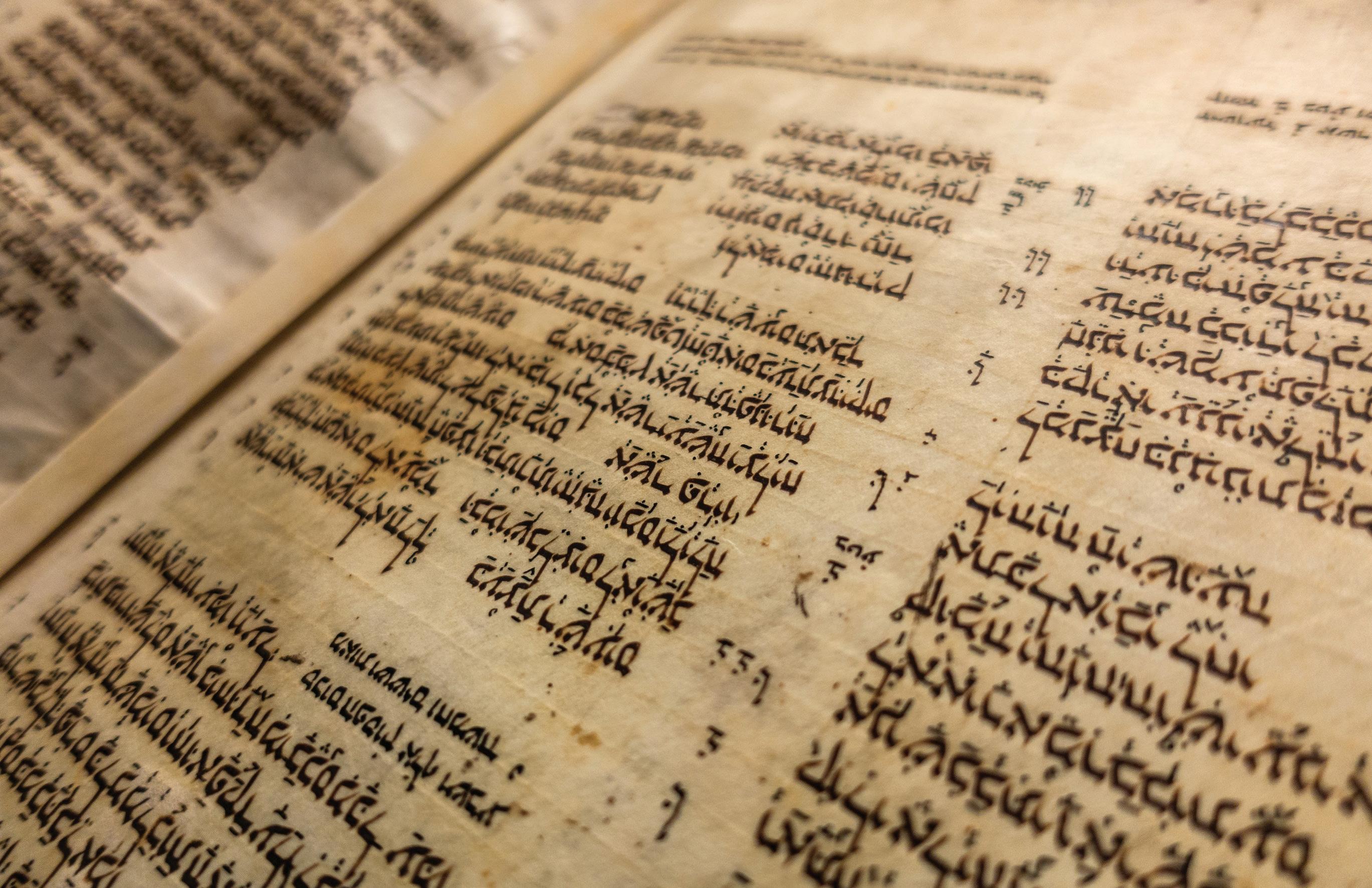

There is, however, one text that the Jewish people have preserved, copied and transmitted for over 3,300 years in a format unchanged since antiquity – the Torah scroll. The scroll, written on parchment in an ancient script, does not contain vowel sounds or punctuation, has variations in the spelling of words as either plene or defective, and has words that are pronounced differently than they are written. All this information is part of the Oral Torah. As the Talmud puts it, “Rabbi Yitzḥak said: The vocalisation of the scribes, and the ornamentation of the scribes, and the verses with words that are read but not written, and those that are written but not read are all laws transmitted to Moses from Sinai.”4

Concerned that this information would be lost, a group of scholars, known as the Masoretes, decided to write down everything in the Oral Law regarding the text of the Torah scroll. They vowelised the text (nekudot), recorded the cantillation notes which provide punctuation (taamei hamikra or tropp), listed every possible textual variation, and indicated every form of spelling and pronunciation of the sacred text. Because of our veneration for the Torah scroll none of this information may be recorded in the scroll itself – the scroll is pure, unadulterated, pristine, ancient Torah – nothing else.5

The Masoretes, primarily the Ben Asher family, lived in the 10th century in Tiberias, on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. At that time Tiberias was the scholarly, political, economic and cultural capital of Israel and Muslim conquest had brought with it the import of paper-making technology from China. The Masoretes were at the right time and place to engage in the monumental task of preserving the text of the Bible and its Oral traditions. They paid attention to every single letter, to spaces between paragraphs and chapters, to the text’s layout, differences between the written and spoken text and counted the occurrence of words throughout the entire Bible.

After years of work they produced a codex, a book that contained all the above information both within the text and as marginal notes known as Mesorah.6

Eventually the codex, called the Crown, or Keter, was moved to Jerusalem sometime in the 11thcentury, but it was apparently stolen by Crusaders at some point. History gets a little murky here, but it seems that the codex was ransomed from the Crusaders at great cost to the Jewish community.

In the 12th century the codex turned up in Fostat, (a city that eventually became Cairo) where there was a large, well-established Jewish community.7 The most famous sage of Fostat was Moses Maimonides, who saw the codex and wrote, “The codex on which I relied on for these matters was a codex renowned in Egypt, which includes all the 24 books [of the Bible]. It was kept in Jerusalem for many years so that scrolls could be checked from it. Everyone relies upon it because it was corrected by ben Asher, who spent many years writing it precisely and checked it many times.”8

In 1375, Maimonides’ great-greatgreat grandson, David, moved to Aleppo in Syria and it is believed that he brought the treasure with him. The codex became known as the Crown of Aleppo, Keter Aram Tzovah, and it was kept by the Syrian Jews in the Great Synagogue of Aleppo, under intense security, brought out only for the occasional consultation or perusal of scholars.

The Crown remained in the synagogue until November 1947. Due to the rise of Arab nationalism and the pro-Nazi sympathies of the Syrian regime, many believed that the Crown was in danger. Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, an historian and Zionist leader, who later became second president of the State of Israel, made attempts to bring the codex to Israel but was unsuccessful.

In November 1947 the Syrian government instigated riots against the Jewish population and the Great Synagogue of Aleppo was burnt down. Rumours flew regarding the fate of the codex – some said it was destroyed, some said it was saved, some claimed that it was saved by one person, others claim a different saviour. Two eminent scholars of the codex, Chaim Tawil and Bernard Schneider, list no less than seven different accounts of the fate of the Crown.9

After the State of Israel was established and the border with Syria was closed efforts to recover the Crown became much more difficult. Yitzchak Ben-Zvi enlisted the aid of the Israeli security services and involved diplomats, spies and rabbis in returning the Crown to Israel. Unit 504, a top-secret section of the Israeli Military Intelligence specialising in infiltration of agents into Arab countries, was also involved (my security clearance is not high enough to confirm this). This was the unit that took part in obtaining the Dead Sea Scrolls later.

Here again, there are many different versions of what happened, but eventually the Crown, albeit with missing sections and damaged by fire and fungus, came back to its birthplace, Israel. Now the focus turned to preserving the Crown and researching the surviving parts.

A manuscript written in Tiberias, Israel in the 10th century, travelled to Jerusalem, was “kidnapped” and ransomed, taken to Egypt, from there to Aleppo, Syria and from there back to Jerusalem. The Crown of Aleppo is a symbol of Jewish continuity, of Jewish devotion to the Torah and of the return of the Jewish people to its ancient homeland.

For further reading: The Aleppo Codex: A True Story of Obsession, Faith and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible, by Matti Friedman 1. Plato, Phaedrus 14, 274c-275b 2. See Babylonian Talmud, Berachot 7b, Midrash Tanchumah (Buber), Parshat Noach 3 3. E. E. Urbach, “Introduction to the Mishnah and to One Hundred Years of Its Scholarship”, Scholarship in Jewish Studies, Vol. 2, (Jerusalem 5758) pp. 716738 4. Babylonian Talmud, Nedarim 37b 5. Code of Jewish Law, Yoreh Deah 274:7 6. Crown of Aleppo: The Mystery of the Oldest Hebrew Bible Codex – Hayim Tawil and Bernard Schneider – Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 2010 pp. 15-27 7. Ibid. pp. 47-56 8. Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Laws of the Torah Scroll 8:4 9. Crown of Aleppo pp. 82-83

The scandalous history of the Aleppo Codex

CONSIDERED OPINION Abortion in Jewish law

DANIEL EISENBERG, M.D. COURTESY: AISH.COM

The Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America (Orthodox Union) recently issued the following statement regarding the US Supreme Court’s potential overturning of Roe v Wade:

The Orthodox Union is unable to either mourn or celebrate the news reports of the U.S. Supreme Court’s likely overturning of Roe v Wade. We cannot support absolute bans on abortion – at any time point in a pregnancy – that would not allow access to abortion in lifesaving situations. Similarly, we cannot support legislation that permits “abortion on demand” – at any time point in a pregnancy – and does not confine abortion to situations in which medical (including mental health) professionals affirm that carrying the pregnancy to term poses real risk to the life of the mother.

As people of faith, we see life as a precious gift granted to us and maintained within us by God. Jewish law places paramount value on choosing life and mandates – not as a right but as a responsibility – safeguarding our own lives and the lives of others by behaving in a healthy and secure manner, doing everything in our power to save lives and refraining from endangering others. This concern for even potential life extends to the unborn foetus and to the terminally ill.

Abortion on demand – the “right to choose” (as well as the “right to die”) – are thus completely at odds with our religious and halachic values. Legislation and court rulings that enshrine such rights concern us deeply on a societal level.

Yet that same mandate to preserve life requires us to be concerned for the life of the mother. Jewish law prioritises the life of the pregnant mother over the life of the foetus such that where the pregnancy critically endangers the physical health or mental health of the mother, an abortion may be authorised, if not mandated, by halacha (Jewish law) and should be available to all women irrespective of their economic status. Legislation and court rulings – federally or in any state – that absolutely ban abortion without regard for the health of the mother would literally limit our ability to live our lives in accordance with our responsibility to preserve life.

The extreme polarisation around and politicisation of the abortion issue does not bode well for a much-needed nuanced result. Human life – the value of everyone created in the Divine Image – is far too important to be treated as a political football.

Abortion in Jewish Law

The traditional Jewish view of abortion does not fit conveniently into either “pro-life” of “pro-choice” camps in the abortion debate. Judaism neither bans abortion completely, nor does it sanction indiscriminate abortion "on demand”.

A woman may feel that until the foetus is born, it is a part of her body and therefore she retains the right to abort an unwanted pregnancy. Does Judaism recognise a right to "choose" abortion? In what situations does Jewish law sanction abortion?

To gain a clear understanding of when abortion is permitted (or even required) and when it is forbidden requires an appreciation of certain nuances of halacha (Jewish law) which govern the status of the foetus.1

The easiest way to conceptualise a foetus in Jewish law is to imagine it as a full-fledged human being – but not quite.2 In most circumstances, the foetus is treated like any other "person”. Generally, one may not deliberately harm a foetus. But while it would seem obvious that Judaism holds accountable one who purposefully causes a woman to miscarry, sanctions are even placed upon one who strikes a pregnant woman causing an unintentional miscarriage.3

That is not to say that all rabbinical authorities consider abortion to be murder. The fact that the Torah requires a monetary payment for causing a miscarriage is interpreted by some rabbinical scholars to indicate that abortion is not a capital crime4 and by others as merely indicating that one is not executed for performing an abortion, even though it is a type of murder.5 There is even disagreement regarding whether the prohibition of abortion is biblical or rabbinic. Nevertheless, it is universally agreed that the foetus will become a full-fledged human being and there must be a very compelling reason to allow for abortion.

As a general rule, abortion in Judaism is permitted only if there is a direct threat to the life of the mother by carrying the foetus to term or through the act of childbirth. In such a circumstance, the baby is considered tantamount to a rodef, a pursuer6 after the mother with the intent to kill her. Despite the classification of the foetus as a pursuer, once the baby's head or most of its body has been delivered, the baby's life is considered equal to the mother's, and we may not choose one life over another, because it is considered as though they are both pursuing each other.

It is important to point out that the reason that the life of the foetus is subordinate to the mother is because the foetus is the cause of the mother's lifethreatening condition, whether directly (e.g. due to toxemia, placenta previa or breach position) or indirectly (e.g. exacerbation of underlying diabetes, kidney disease or hypertension).8 A foetus may not be aborted to save the life of any other person whose life is not directly threatened by the foetus, such as use of foetal organs for transplant.

Judaism recognises psychiatric as well as physical factors in evaluating the potential threat that the foetus poses to the mother. The degree of mental illness that must be present to justify termination of a pregnancy has been widely debated by rabbinic scholars10 without a clear consensus of opinion regarding the exact criteria for permitting abortion in such instances.11 Nevertheless, all agree that were a pregnancy to cause a woman to become suicidal there would be grounds for abortion.12

As a rule, Jewish law does not assign relative values to different lives. Therefore, almost most major poskim (rabbis qualified to decide matters of Jewish law) forbid abortion in cases of abnormalities or deformities found in a foetus. Rabbi Eliezar Yehuda Waldenberg is a notable exception. Rabbi Waldenberg allows first trimester abortion of a foetus that would be born with a deformity that would cause it to suffer and termination of a foetus with a lethal foetal defect such as Tay Sachs up to the seventh month of gestation.14 The rabbinic experts also discuss the permissibility of abortion for mothers with German measles and

AROUND THE COMMUNITY

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY

Our nation is only a nation by virtue of its Torah – Saadya Gaon Why do Jews transcend history? The astonishing survival, energy and creativity of the Jewish people across millennia has mystified the masses. Modern luminaries such as Mark Twain and Winston Churchill have eloquently expressed their wonderment at the seemingly endless capacity for perseverance and regeneration that characterises the Jewish nation. What is the secret formula that enables us to survive almost anything, emerging victorious and even optimistic?

Through our preservation of our heritage, our heritage preserves us. The relationship between the Jewish nation and the Torah is unique, without precedent or parallel. Jewish scholars and lay people alike have spent countless centuries obsessing over every letter, every word and even gaps between the words. It has served as our lighthouse through stormy times, our inspirational muse during periods of joy and consistent anchor during eras of turbulence. Regardless of events in the outside world, Jews can always turn to our text, engaging with the celebrated ideas and personalities that live on through our great story. Empires rise and fall; civilisations conquer the world and fade into dust; plagues, war and revolutions ravage the landscape – and Jews still pore over their beloved pages, attempting to tease out the lessons in every section. This private dialogue with infinity and constant communion with a superior plane of reality has preserved an enduring sense of Jewish pride, identity and purpose, regardless of circumstances. There were Torah study groups in Auschwitz, just as there are Torah study groups in the corner offices of New York, London, Sydney and Melbourne today.

Although some scholars may spend entire careers focusing over the works of a Shakespeare, a Dante or a Dostoyevsky, they will always find themselves confronted by the limitations … the simple mortality of the human author. It is precisely this point that sets the Torah apart.

As a reflection of the Divine, the Torah is completely inexhaustible, containing infinite layers of meaning. Millennia of commentaries and super-commentaries have analysed and excavated every component, squeezing all possible meaning from these tantalizing texts. Yet – as any Torah scholar worth his or her salt will tell you – we have barely scratched the surface: every new reading yields further questions, explanations, advances or frustrations in our understanding. The hope of producing the final word, the conclusive explanation, of even the smallest element of the Torah is a fanciful dream. We can never hope to obtain finality; all we can strive for is to be part of the conversation.

It is astonishing that Jews across cultures and eras have all sought and discovered, profound spiritual inspiration and moral instruction through the study of the same text.

Could it be possible that Jews residing in the Rome of the Caesars, the Baghdad of the Caliphs and the Paris of Napoleon all believed that the Torah was talking directly to them, that it was prescribing a way of life that informed and enriched their own unique situation? Amazingly, the answer is a resounding “yes”. The Torah is both timeless and timely. Every person, regardless of physical, emotional, psychological or spiritual disposition, can discover and rediscover endless treasures in this unparalleled trove of textual treasure.

That includes us. Having spent many years studying with some of the finest scholars and expositors of our generation, I am convinced that the Torah speaks directly to us, perhaps more so than ever before. Our current generation – those whose lives will span the bulk of the 21st century – display a desperate need for spiritual content and contentment. Although our lives are being made progressively easier, safer, longer and more leisurely by the relentless advance of science and technology, many feel an inner emptiness, an absence of objective meaning that would imbue our existence with true direction and purpose. Many try desperately to fill it with anything, from sports teams and TV shows to protest movements and recreational drugs. While some may find temporary relief through some of these endeavors, they are all symptomatic of a greater cause: people are crying out for something beyond themselves, a greater truth or cause that will anchor their lives. But nothing temporal will ever be able to bridge the void in the human soul that reaches beyond. This sits at the heart of Shavuot and why we celebrate the greatest gift we ever received – the Torah.

Shavuot – the day that shook the world

For more insights, go to: https://www.rabbibenji.com

Abortion in Jewish law

From page 11

babies with prenatal confirmed Down syndrome.

There is a difference of opinion regarding abortion for adultery or in other cases of impregnation from a relationship with someone biblically forbidden. In cases of rape and incest, a key issue would be the emotional toll exacted from the mother in carrying the foetus to term. In cases of rape, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Aurbach allows the woman to use methods which prevent pregnancy after intercourse.15 The same analysis used in other cases of emotional harm might be applied here. Cases of adultery interject additional considerations into the debate, with rulings ranging from prohibition to it being a mitzvah to abort.16

I have attempted to distil the essence of the traditional Jewish approach to abortion. Nevertheless, every woman's case is special and the parameters determining the permissibility of abortion within Jewish law are nuanced, subtle and complex. It is crucial to remember that when faced with an actual patient, a competent halachic authority must be consulted in every case. 1. While there is debate among the rabbis whether abortion is a biblical or rabbinical prohibition, all agree on the fundamental concept that abortion is only permitted to protect the life of the mother or in other extraordinary situations. Jewish law does not sanction abortion on demand without a pressing reason. 2. Igros Moshe, Choshen Mishpat II: 69B. 3. Shulchan Aruch, Choshen Mishpat, 423:1 4. Ashkenazi, Rabbi Yehuda, Be'er Hetiv, Choshen Mishpat 425:2 5. Igros Moshe, ibid 6. Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Laws of Murder 1:9; Talmud Sanhedrin 72B 7. Oholos 7:6 8. See Steinberg, Dr. Abraham; Encyclopedia of Jewish Medical Ethics, "Abortion and Miscarriage," for an extensive discussion of the maternal indications for abortion. 9. Igros Moshe, ibid 10. See Encyclopedia of Jewish Medical Ethics. P. 10, for references. 11. See Spero, Moshe, Judaism and Psychology, pp. 168-180. 12. Zilberstein, Rabbi Yitzchak, Emek Halacha, Assia, Vol. 1, 1986, pp. 205209. 13. Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Aurbach and Rabbi Yehoshua Neuwirth cited in English Nishmat Avraham, Choshen Mishpat, 425:11, p. 288. 14. Tzitz Eliezer, Volume 13:102. 15. Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Aurbach and Rabbi Yehoshua Neuwirth cited in English Nishmat Avraham, Choshen Mishpat, 425:23, p. 294. 16. See excellent chapter in English Nishmat Avraham, Choshen Mishpat, 425 by Dr. Abraham Abraham, particularly p. 293.

Judaica quiz answers

1. Shavuot translates from the Hebrew as ‘Weeks’ – and this festival always takes place seven weeks after Pesach 2. This proves that Mt Sinai had foliage, hence the custom to decorate the shule and home with tree branches and greenery 3. Torateinu – Our Law 4. Mount Horeb 5. The Counting of the Omer - otherwise known as Sefirah 6. Tikkun Leil Shavuot – the night of learning on first night Shavuot. Instituted to remedy the fact that the Israelites slept through the night of G-d’s revelation. This is why according to Isaiah, G-d said: ‘When I came, why was there no one? When I called, why was there no one to answer?” 7. The Wheat Harvest 8. Some sit to differentiate Jewish customs from earlier groups such as the Karaites who opted to stand. Perhaps, it could be to reduce the importance of the Ten Commandments in the eyes of the general public because other religions such as Christianity insisted that these Ten Commandments were more special than all others. It could also be because when we learn, we typically sit and study, and listening to Torah reading is equal to attending a study lesson 9. Naomi 10. The Hebrew word for ‘no’ or ‘don’t’ – LO. It occurs 13 times. 11. On Shavuot the laws were given; so the Israelites learned about the laws of Kashrut (dietary laws) for the first time. Rather than consume the meat that had previously been prepared (not in line with the new dietary laws), they ate only dairy foods in the immediate aftermath of the giving of the Torah. We replicate this each year on Shavuot by eating some dairy produce 12. True. This festival in a sense concludes the festival of Pesach 13. Day 2 in the Diaspora 14. c) A liturgical poem recited annually on Shavuot 15. St Catherine’s Monastery 16. 1923 and 1956 17. One way that Ashkenazi Jews beautified their homes for Shavuot was by creating and displaying paper cuttings. Called in Yiddish, shevuoslach (or shavuosl) and royzalach (or raizelach) – literally meaning little Shavuots and little roses – the paper cuttings were mounted on windows, so they would be visible both indoors and out 18. Rembrandt and his wife 19. The Zodiac sign of Sivan is Gemini (twins). Following Aries (ram) and Taurus (ox), the Gemini (twins, te’omim in Hebrew) is the first Zodiac sign that is in human form (the only other is Virgo, the virgin). The sages explain that this is appropriate for the month when we received the Torah, as only a human can extol, clap and dance with joy over this momentous event 20. Esther 8:9 “Then were the king's scribes called at that time, in the third month, which is the month Sivan …” 21. Tu b’Av – the minor festival on the 15th of Av 22. After narrowly escaping the Nazi onslaught in France, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-1994), and his wife, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka Schneerson (1901-1988), arrived in the United States of America on the 28th of Sivan in the year 5701 (1941) 23. Ruth was King David’s greatgrandmother 24. b) Twice 25. King David was born and also died on Shavuo