4 minute read

An island’s hold on family

Memoir finds Vinalhaven was home base

families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Advertisement

Because it is a compilation, topics end up being covered multiple times. Garlic is an example, with repetitious advice. No time frame is provided with dates of articles, so references to “this summer” or “that season” are somewhat meaningless.

I think when these were columns, one or two platitudes per column could have been bearable. But to read the collection in its entirety, the book starts to feel saccharine, sappy, and cliche-ridden.

The pictures are great, and there are many. And I do feel inspired to start growing ginger and sweet potatoes, for which she provides ample directions. This book could be a step towards what I suspect King would do brilliantly— combine her gardening advice and health concerns with her hearty can-do attitude and generous enthusiasm in a book aimed at a younger audience. I think she’d make a great “coach” who could get more kids growing food.

Another Mainer, Roger Doiron of Scarborough, founder of Kitchen

Gardens International, was successful in convincing First Lady Michelle Obama, in her early months in the White House, to start a vegetable garden on the grounds. Not only did she do that, but she brought children from Washington D.C. elementary schools in to help and learn.

There is evidence to support that when children work in gardens, it has a positive impact on many areas of their lives, including school performance. They practice skills like planning and patience.

And as King writes, “We have so much to learn about life, just from the humus under our feet.” She continues, “If we can care for our organic matter, perhaps we will have more nutritious foods to eat, microbes for health, and a sponge to soak up the rain. Let us care for our humus... our ecosystem and microbiome—the Earth depends on our help.”

Who more importantly needs to hear this concern than children growing up today?

REVIEW BY TOM GROENING

As the state ferry approaches North Haven in the Fox Island Thorofare, my eye goes to the large, sprawling cottagestyle mansions that line neighboring Vinalhaven’s cliffs to the south.

The buildings, which in the offseason are shuttered, or at least without signs of life, date to the late 19th or early 20th century. I often muse to myself about the people who built these grand escapes, and what role they served in their lives and the lives of their families, even now, generations later.

Is their appreciation of Maine island life less or more than the rest of us who live here year-round, and maybe get to visit an island once in a while? The grandeur of the homes suggests wealth, which reminds me of the line from Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: “All happy in Europe during World War II, and it marked him—as it did most—so that she understands him in Before The War and After The War terms.

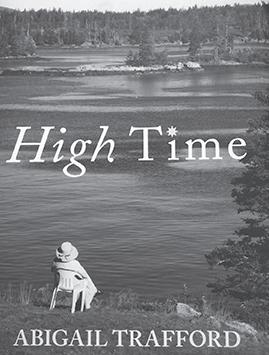

Well, no need for me to muse any further. Abigail Trafford’s memoir High Time opens the shutters on at least one of those mansions, and though Trafford has found peace and yes, even happiness in her 80s, there is also some of Tolstoy’s unique unhappiness in what appeared to be an otherwise charmed family life.

Reading and speaking about the book at the Vinalhaven Public Library in late July, she said it represented an accounting, a making sense of a family and a personal life marked not by privilege and good times under sunny skies on a Maine island, but by broken lives and broken relationships.

She worked as a reporter and editor for The Washington Post and U.S. News & World Report, covering such envied beats as the U.S. space program…

“It was high time to come clean,” she said at the event, invoking the title of the book. “Time” is a refrain in her writing, with earlier books titled My Time, As Time Goes By, and Crazy Time.

Yes, Trafford’s mother and father were well educated and hailed from old money, but that tells only part of the story. Her father saw prolonged action

Correspondence she quotes between her father fighting in Europe and her grandfather back home reveal a quiet fatalism in the soldier. Though he was a sensitive soul who lived to play music—photos in the memoir bear witness to the family’s habit of gathering around a piano at the Big House in Maine— he stuffed his feelings away. Her mother suffered several miscarriages before bearing Abigail and a sister and brother. Her brother was diagnosed with autism. The trauma of the miscarriages seems to have triggered mental illness, Trafford writes, and her mother tried to treat it with drugs and alcohol.

Trafford’s adult life was far from charmed, though it brought opportunity. She worked as a reporter and editor for The Washington Post and U.S. News & World Report, covering such envied beats as the U.S. space program in the 1960s, but after her first divorce, trying to raise two daughters alone, she had to take in boarders to pay the bills.

Rather than write a chronology, the narrative bounces from vignettes to biographical sketches of the extended family, the latter of which seemed at times a lot to ask of a reader. Which uncle, and whose second wife are we talking about here?

But Trafford’s perceptive and affectionate takes on this colorful cast of characters are rich and they further render the nuances of a happy, unhappy family. And those characters provided caretaking and wisdom, crucial to the girl and woman she became, so valuable given that her mother was missing in action.

COVID presents a coda to the life that orbited far around the globe but centered on Vinalhaven. Like other COVID refugees from urban areas, Trafford and her daughters and grandchildren drank deeply of the island, hunkering down in the house she and a husband had built near the Big House.

Like the seasoned journalist Trafford is, she is well equipped to examine her life and carry a reader along its twists and turns, its ups and downs. And though she repeatedly asserts that Vinalhaven is what kept her grounded, I think she would have found her life’s calm mooring without it.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may contacted at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.